Can China export deflation to the rest of the world?

In a world in where much of the world is grappling with inflation, it might seem strange that inflation is virtually non-existent in China. In fact, in data released this week, inflation on an annual basis just hit zero in June.

Meanwhile, producer price inflation (also called factory gate inflation) is negative, at -5.4% in the year to June, and has been in deflation for nine consecutive months.

How is this possible?

While it might seem great for China that it isn’t experiencing the inflation problem that is occurring in the West, deflation is never usually a good sign for an economy.

Domestic demand in China is weak. China’s economy is still recovering from zero covid and it hasn’t had the same scale of stimulus that occurred in places like the US, Europe, Australia, etc.

Another reason for the divergence is because China has tended to gravitate towards stimulus which ends up boosting supply, as opposed to boosting demand, such as support for businesses and industry and spending on infrastructure. Meanwhile, post-covid stimulus in the West has centred on handouts to households, which has in turn helped lift demand and inflation.

Not one form of stimulus is better than the other, but given that demand in China is weak, China would benefit from some consumer-led stimulus, instead of the infrastructure spending. Whether authorities will provide that form of stimulus is another story (which is in the works 😊).

But back to the original question – could weak Chinese inflation, or even deflation, bring down inflation in other parts of the world?

The notion of China exporting deflation is not new – in the early 2000s, the rise of China as a manufacturing powerhouse helped to bring down the cost of goods around the world.

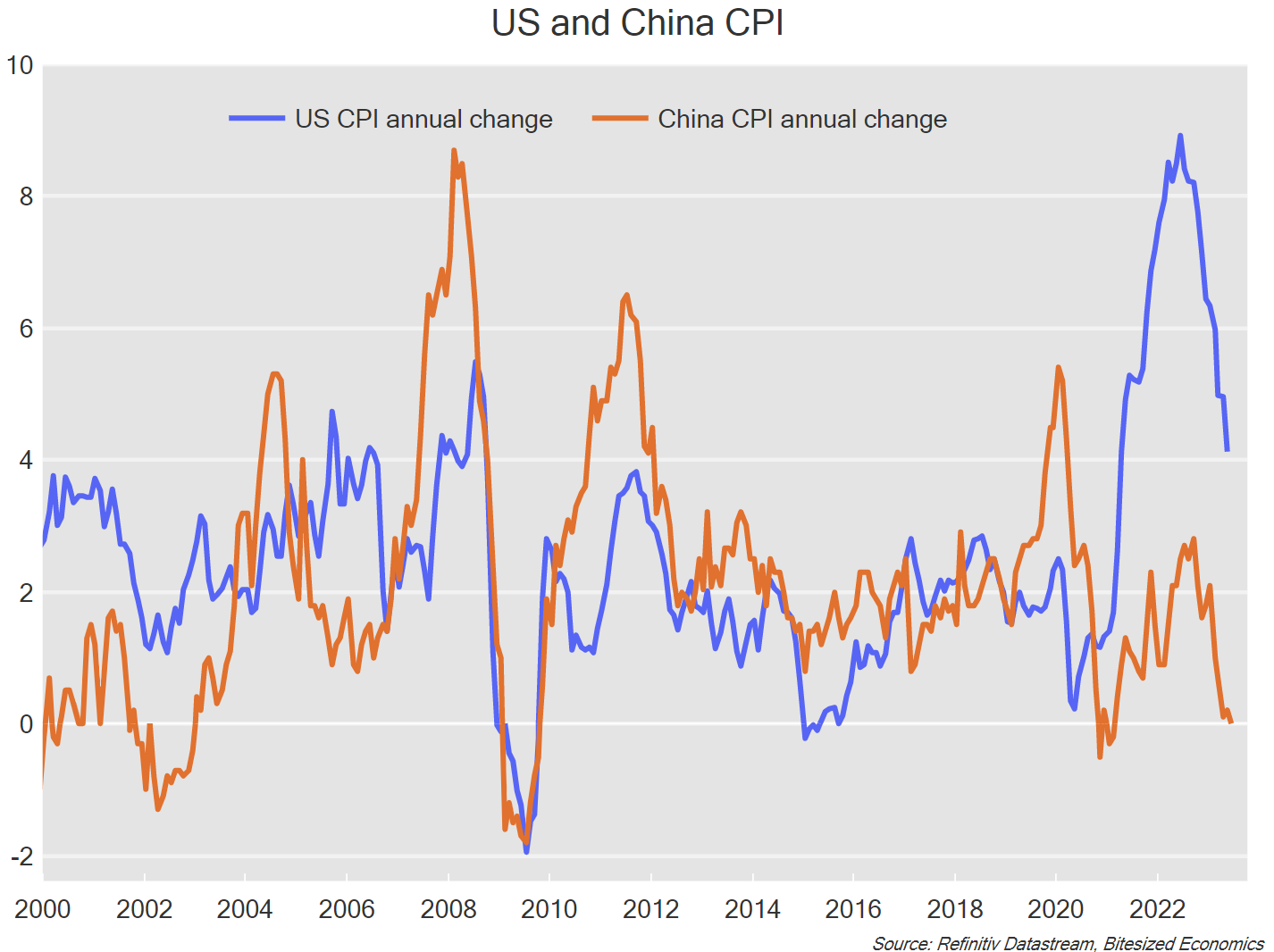

And yes, there has been a reasonably close relationship over time between inflation in China and inflation in the US:

But unfortunately, there is good reason that the disinflationary settings in China, will not translate as easily to the rest of the world as in the past. Here are three key reasons why not:

1. Firstly, strong demand in advanced economies have pushed up domestic inflation.

The major impact on inflation from low-cost production can impact goods, or what economists call “tradables” inflation. But it is the domestic, or non-tradables inflation that central banks are most concerned about and doesn’t come down as easily. This stickier part of inflation is generally coming from services which isn’t as easily imported.

Another sign of persistent domestic inflation is wages growth. Most measures of wages in the US are more elevated than were in the 2000s period.

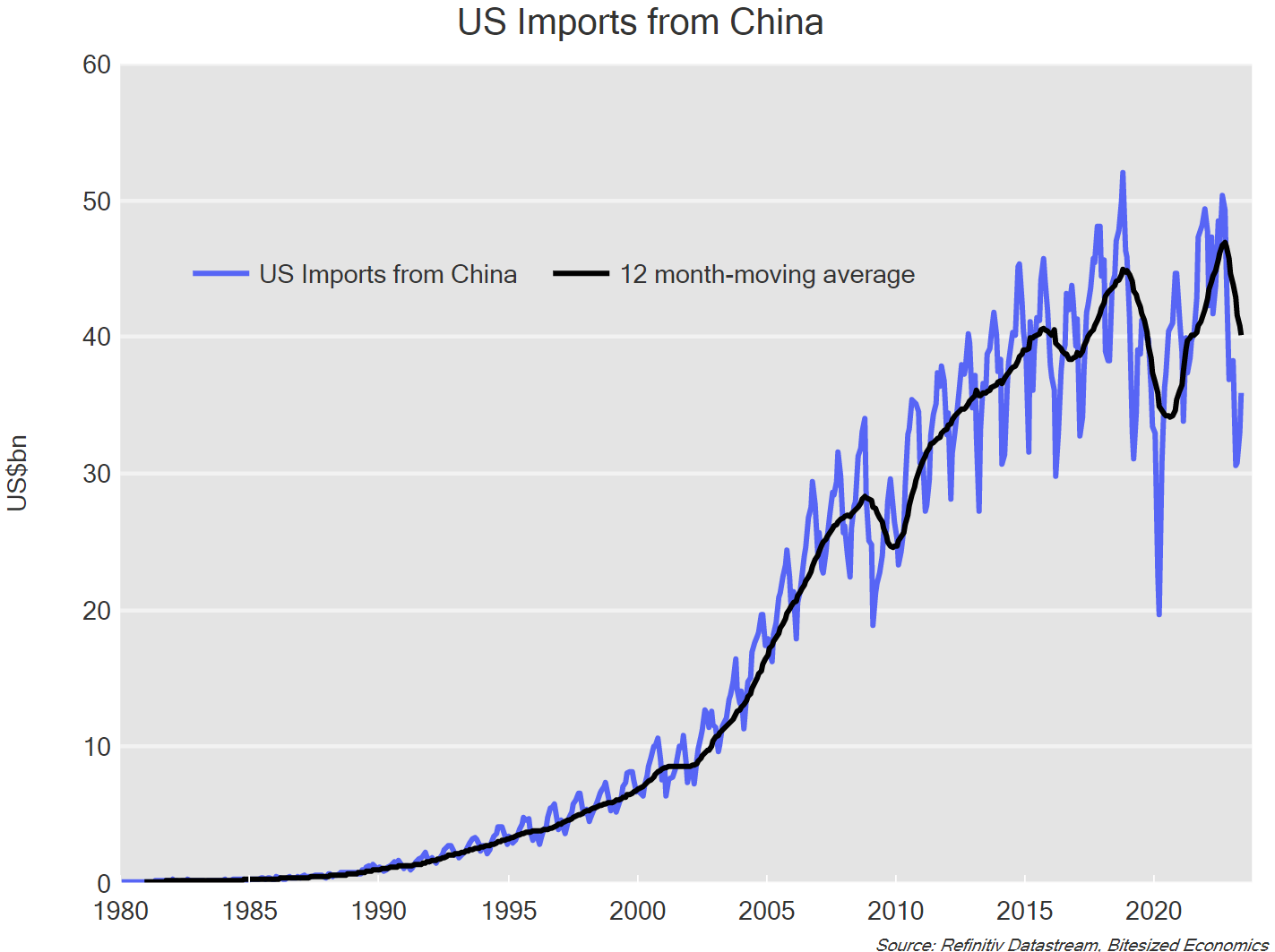

2. China isn’t exporting as much low-cost manufacturing to the US as it used to.

Indeed, six months after China abandoned zero covid, Chinese imports to the US have yet to recover to its pre-pandemic highs.

Perhaps there is a lag impact in recovering from covid lockdowns, it might be due to trade barriers and geopolitical tensions, or it might also relate to long-running readjustment of supply chains of low-cost manufacturing away from China.

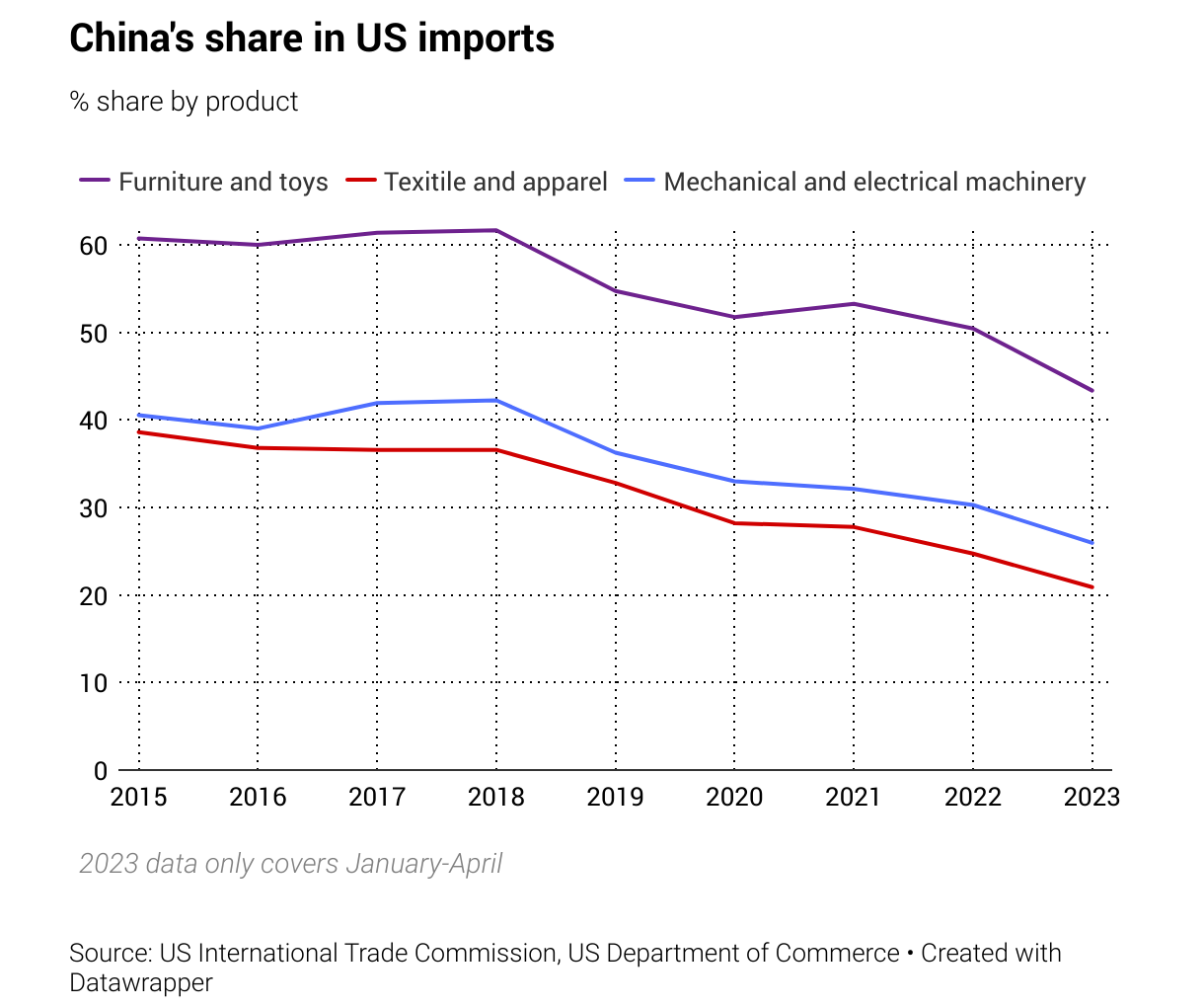

1. This change in the source of import mix for the US also likely reflects a shift within China itself and in the strategic aim of the CCP the (Chinese Communist Party), towards higher-value added manufacturing and technology.

It was the policies throughout the 2000’s that supported Chinese industries that led to the surge in manufacturing in China and the title of being the world’s factory. As well as keeping global inflation lower than it otherwise would be, it has also led to the major global imbalance that we are now seeing the world today, such as China’s huge accumulation of foreign exchange reserves.

Today’s policies still appear to be geared towards supporting production, just higher-end manufacturing instead of lower-end, which can sometimes directly compete with production in advanced economies. In absence of trade barriers, this would be disinflationary, however in a world of “derisking” it is hard not to see tariffs or import restrictions being put in place.

Basically, the ability for China to export disinflation will depend on the ability to export goods to the rest of the world, and importantly to advanced economies which are now experiencing high inflation. Current trade flows, at least to the US, suggests that Chinese imports will not have the same deflationary impact as in the 2000s. Moreover, elevated domestic inflation and growth in wages in advanced economies indicate that inflationary forces are stronger than any time in the past couple of decades.

That doesn’t mean inflation won’t come down. It just means that lower inflation won’t come magically out of nowhere. Higher unemployment and weaker demand will still likely be necessary to get there.

5 topics