Navigating a Pandemic: the Art

Kasa Investment Partners

We can think of any investment decision as the coming together of an object, data and analysis, with a subject, the decision maker. This decision maker may be a person or a computer algorithm. We can further breakdown the decision maker into our perception and our judgement. How clearly are we seeing things as they are? How accurate are we in predicting how things will be in the future? From my experience, neither our perception nor our judgement are static. They are like rivers, constantly changing, depending on the many underlying conditions that we have and are experiencing.

The Art of Investing is all about consciously putting in place conditions that allow us to more clearly see how things are and improve the accuracy of our judgement about the future.

I have been providing a window into Kasa’s investment process using Xero as a case study. I broke down the approach into three elements: the Science, the Legwork and the Art. Today, I’d like to share about the third element, the Art of Investing, but instead of using Xero, I’ll be using the current COVID-19 pandemic as this provides a clearer view of what this is and how it’s applied.

the root problem - our sense of self

We’ll start by exploring the factors shaping our perception before relating them to investing. With experience, and the guidance of Zen teachings, I have come to recognize an implicit assumption underlying my perception: there is a subject, an ‘I,’ which interacts with objects ‘the world, outside of this I.’ In other words, there is a dualistic construct, where things are separate from each other and in particular, there exists an entity ‘I’ which is separate for all other things.

The sense of self, amongst other things, leads to the formation of our ego. The ego is the result of seeing the world through a dualistic lens – breaking up reality into many components, while not recognising that these components are just aspects of the same whole. The dualistic view leads to an ‘I’ which is separate from everything else, it was born and it will die. In some ways of course this perception accords with our experience, and it is thus understandable that we take it to be a complete picture of reality. We see ourselves here as a wave of life that rises and falls on the ocean. As we look more deeply though we see that there is a whole other perspective. There, we are the very world around us, and thus in some ways existed before our birth and will continue after our death; we are not just the wave but the ocean itself.

This view can be conceptualised through Indra’s Net which I wrote about in Investing in Xero: the Legwork.

An interesting notion I came across in my Zen training is that all phenomena are dependent on, and penetrated by all other phenomena. Looking at a flower, for example, we can see it is dependent on the sunshine, the nutrients in the soil, the rain and so on. If you take any one of these conditions away, the flower would not be the way it is. Looking deeper, we see that each of these conditions is, in turn, dependent on a series of other conditions. Looking in this way we can see the interdependent co-arising of all things. Indra’s net is an analogy that is often used to help students grasp this rather large concept.

So how does this relate to investing? Well, there is a strong energy within us that wishes to keep the atoms and molecules that constitute ‘the self’ intact – we sometimes refer to this as our survival instinct. If there is a threat, or a perceived threat, a series of emotions are triggered which drive our behaviours. The energy of fear, for example, can lead to a fight, flight or freeze response.

Our sense of self can take many forms and the same survival instinct is activated to protect them all. ‘I am this body,’ or ‘I am someone who is good at investing,’ or ‘I am responsible for my family’s financial wellbeing’. When our sense of self comes under threat, there is a strong reaction within to protect it. So if stock prices fall, we may feel fear as our core identity may be threatened. Or if someone questions our investment thesis we may find ourselves getting very defensive or aggressive. Once this energy kicks in – which sometimes is referred to as our ego – we become susceptible to making mistakes.

The pandemic is an interesting situation, because not only did it ‘threaten’ the sense of self in the financial realm, it also threatened our lives, and the lives of our loved ones in the realm of form.

Over the years I have become very familiar with the emotion of fear, particularly with respect to investment decisions, as deep within I know I don’t know. When I have looked into the roots of that fear, underneath it is always the dualism, the sense of self. This fear then causes distortions in my perception – I may experience tunnel vision, where my mind prioritizes away things that don’t seem relevant to the perceived threat, such as our daughter excitedly telling me about her latest painting. It can also over-emphasise the downside risks, thereby impairing my judgement – wow, I hadn’t appreciated how weak the balance sheet is; or, I can’t see how the economy isn’t going to end up in a deep recession; and so on.

So, for me, the perception that there is an ‘I’ leads to a false sense of self that needs protecting. This generates, amongst other things, the emotion of fear, distorting my capacity to see things as they are and impairing my judgement. It is important to note that the sense of self is essential to keeping the atoms and molecules that constitute us together, so it does serve a very useful purpose. So we are not setting out to remove it, rather recognising when it is moving us in ways that are not helpful. As you may appreciate, there are further layers to this onion, including the various aspects of our consciousness, but let us leave this rabbit hole for another day.

seeing things from a different perspective

I was in my early twenties when I first started exploring my inner world through contemplative teachings and practices originating from the East. Growing up in a secular family, and being trained by the Australian education system, I brought a healthy dose of scepticism to new ideas and views not anchored by the scientific process: theory, experiment, result. I soon realised these Eastern teachings took the same scientific approach, but applied it to the inner world, our minds. We would be offered a notion (theory), we would then see if it was consistent with our inner experience and the experience of other students, and if yes, then we would accept it, otherwise we would not: theory, experiment, result.

What kept me exploring was the teachings and practices were not just satisfying an intellectual curiosity, but were proving very useful in navigating life. Further, they were helping me become a better version of myself and, as a byproduct, improving my investment decisions. This is not to say I am a perfect father, husband, son … nor that I don’t make investment mistakes, but I have gradually come to appreciate how this path has, bit by bit, taken me in a more healthy direction.

I’ve also found something paradoxical: if we try to use these teachings and practices to improve our investment skills, they don’t work. The reason is an aspiration to become a better investor is still anchored in a “me versus everyone else” view. This became clear to me when leading the internal mindfulness program at Fidelity which dozens of investment analysts and portfolio managers attended.

These teachings and practices are most effective when we come from a more holistic aspiration, such as cultivating our minds to improve our overall life experience. They help us cultivate positive elements such as self-awareness, focus, clarity, stability, freshness, non-fear, wisdom and so on within us. These factors combine to allow us to see things more clearly, make better investment decisions and live a happier and more harmonious life.

I have found many practices I can use to transform my inner state. ‘Practices’ here don’t mean rituals, incense and Buddha statues, they are anything that cultivates our mind in a positive way, from going for a swim, playing with the kids, gardening and meditating, to watching a teaching which might come through a film or a Zen master. These practices can be broadly divided into those that help settle my mind (and thus see things more clearly) and those that improve my understanding of how things are. And underneath it all, so long as the light of my mindfulness is shining, I am gaining insights which naturally takes me in a positive direction. And, as with most activities, being part of a community of like-minded people helps sustain and accelerate the process.

application of the theory during a pandemic

As the pandemic extended beyond China, my inner state was solid and clear – I reviewed and set the portfolio for a potential imminent economic and financial storm. When the storm started to hit, I shifted my attention to maintaining the inner state – the Art of Investing – knowing there were no immediate investment decisions to be made.

Fear, like most of our emotions, can be contagious. I could feel this coming through many channels: the financial markets, the media, schools, supermarkets, family, friends, and so on. I don’t remember ever being so completely surrounded by this energy. I set about protecting my mind from the excessive and potentially toxic input by reducing my digital consumption.

I preoccupied myself with helping the kids school from home, spend more time in the garden, read non finance books, enjoyed cooking more elaborate meals, went for long walks, all the while knowing the time would come to take advantage of opportunities that would no doubt present themselves.

There was also a stroke of luck – the online meditation support group I’m involved with started getting requests from local groups wishing to transition temporarily online. This allowed me to channel my energies toward something worthwhile, helping others in a time of need. A few friends and I set up over a dozen training sessions, supporting two hundred or so local groups transition online.

It was interesting to see how the emotion of fear protected our society as a whole from COVID-19, motivating people into action. Of course, fear was not a necessary condition to act, but sometimes we seem to need an emotional drive to change our behaviour.

changes to the portfolio

While I reduced down my attention away from the markets, I didn’t completely disengage, continuing to monitor risks to our investments and emerging opportunities. In the last week of March I re-engaged fully and started deploying the cash we held for this type of scenario. The focus initially was on our existing investments, since we understand these the best.

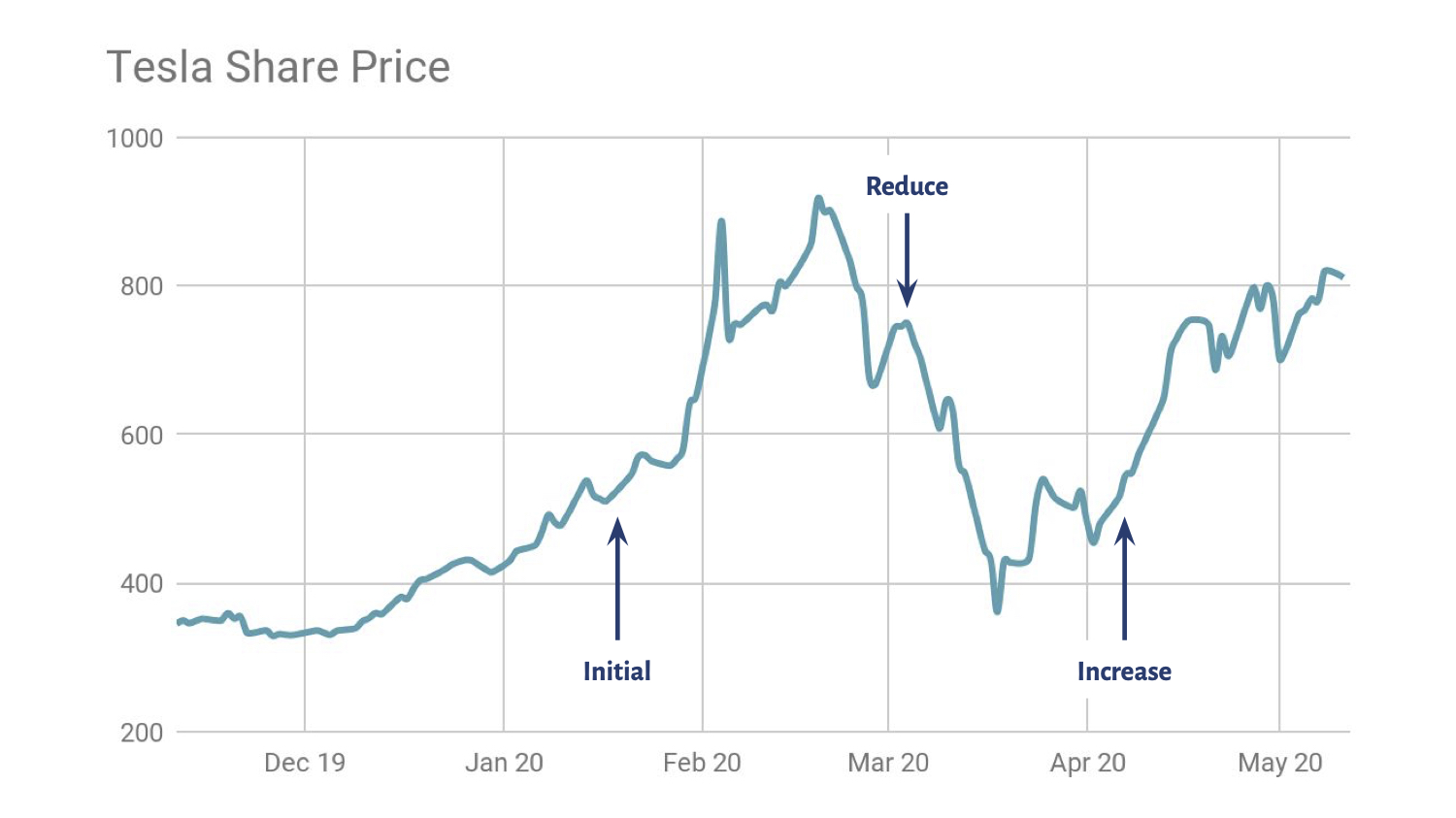

From the last week of March through the first half of April we reduced the cash allocation from 27% to 7%; increasing our holdings in Afterpay, Alphabet, Tesla, Megaport and Netwealth. We exited Hub24, reinvesting the proceeds in Netwealth; and established a position in Microsoft. Each of these decisions, including that of reducing the cash holding, was dependent on my perception of how things are and judgement around how they are likely to be. The quality of this was a function of my capacity to sustain a solid and clear mind – the Art of Investing.

tesla and afterpay

Let’s now go deeper into two specific decisions Tesla and Afterpay. Tesla was the business that concerned me the most heading into the pandemic, and the only one I reduced when I reviewed the portfolio. Afterpay was the stock in our portfolio the market was most concerned about with the share price down 78% from peak to trough. As a reminder the two scenarios we are trying to avoid are 1) the business needing to raise money to survive; and 2) there is some form of structural step down in long term profitability.

Tesla is cyclical (sells new cars), has operating and financial leverage, and was physically not allowed to produce cars in the US due to the social distancing measures. The main risk was of it needing to raise money to survive.

Our first step was identifying the scenario needed for Tesla to run out of cash. Modelling the cashflows in greater detail revealed the US factory needed to be shut for some 9–12 months before the company would run out of cash.

The next step was to assess the likelihood of this scenario coming to pass. The question was what were the conditions needed for US factories to be re-opened: peak new cases, peak deaths, testing & surveillance to identify outbreaks, health system readiness for a potential second wave. China was a useful case study, having gone through the process already. By early April, I gained conviction that the likelihood of Tesla’s US factories remaining closed beyond 9 months was sufficiently low to justify increasing the investment.

Prior to investing in Afterpay I had three major concerns: 1) the unit economics in the US; 2) the likelihood of establishing the ‘winner takes most’ position in the US; and 3) the impact of a recession. The Buy Now Pay Later model is very different to other forms of lending and so I built a detailed model and was surprised to see how resilient it was in a financial downturn. There was also the chance of a demand uplift in a recessed environment. This was the main reason for my not reducing this holding as I set the portfolio for a potential recession.

The market thought otherwise and by mid-late March was essentially pricing in a capital raising. I returned to my ‘recession’ model and built the assumptions needed for it to be forced into raising. The required scenario was:

30% of customers defaulted

‘bad’ customers increased their spend 15% prior to defaulting

‘good’ customers reduced their spending 15%

Afterpay was not able to collect any late fees

operating costs were reduced 40%

This scenario seemed highly unlikely, particularly in light of the Australian government’s Jobkeeper scheme and the company’s decision to require Australian customers to make their first payment upfront – simultaneously reducing risk and releasing capital. One lesson I have learned is to be extra careful when deciding to increase a holding, when its price is falling – the larger the fall, the greater the caution required. And so I decided to not to act.

On 14 April, Afterpay provided a market update revealing the business was highly resilient in a recession – just as the model had predicted. On seeing this, I immediately increased our holding, which was quite fortunate as by the end of that day the price was up 30%! We were able to increase our holding at a price similar to what we paid for our initial investment but with the three major risks having largely abated.

During the pandemic, the ability to retain a clear, stable and focused mind improved my capacity of seeing things as they are and are likely to be. While some of these recent investment decisions will almost certainly turn out to be wrong, that is the nature of investing, I am confident they will, in aggregate, help deliver our investment objective.

the search for certainty

In a way all structures are inherently unstable. Whether it be a soap bubble, a house or a business. They are all dependent on conditions that themselves are dependent on other conditions. And when the underlying conditions are no longer there, they will cease to be. I suspect we all know this at a very deep level, but are not usually confronted with it in our everyday experience.

Investors in equities markets, on the other hand, need to reconcile themselves with having their fortunes tied to structures that are more obviously unstable. From my experience, some do this by diversifying across many assets (I’ve met active equities managers with over 1,000 stocks in their portfolio), confining themselves to ‘cheap’ stocks (low P/E, high dividend yield, etc.), working extremely long hours in the hope of reducing the number of unknowns, restricting themselves to high quality (more stable) businesses, and so on. While all these approaches can be helpful, they cannot remove the uncertainty inherent in investing.

The fear and discomfort associated with the uncertainty though, in investing as in life, appears to me to be a product of our attachment to the view of ourselves as a solid unchanging entity set in eternal struggle against a world from which we are separate. We experience ourselves as a very concrete or separate entity. It helps us live our day-to-day life at a practical level. It also causes us unnecessary pain and anxiety to the degree that we are tightly attached to the "me and mine". When we pay close attention however, we see that what we take as the human being that we are is an ever flowing river of body sensations, feelings and thoughts, which is in constant dynamic interaction with everything that exists. It becomes impossible to draw a meaningful boundary between the I and the not-I and we see that in some ways we are not that separate after all.

the science, art and legwork of investing

I hope these series of notes have helped you better understand how your money is invested. To recap, the starting point is the science, a framework that aligns both with our objective and the fundamental value exchange that takes place when purchasing a share of a business. The next part is the legwork involved with gathering and analysing information. The last element is to be conscious of the distortions and shortcomings of the decision maker and support his or her mind to be in a state that allows a clearer perception of what is, and is likely to be.

Get investment ideas from industry insiders

Liked this wire? Hit the follow button below to get notified every time I post a wire. Not a Livewire Member? Sign up for free today to get inside access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

3 topics

2 stocks mentioned

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.

Expertise

After an extensive career across RBA, Ausbil & Fidelity, Ali founded Kasa Investment Partners to solve the agency problems within the investment industry and derive a more direct relationship between the portfolio manager and the investor.