Should fundies pay clients for underperformance?

Should fund managers place even more of their skin in the game? A respected, global, asset consultant believes so. Whilst there is some merit in this idea, it could make things worse. Maybe asset owners and their advisors might lead the way?

Fund managers paying clients in the event of underperformance?

It never seems to change. Scandals in the financial services industry have contributed to the perception of fund managers as self-centred and acting in a manner which does not align with client interests. Each year, we find more evidence that active fund managers, in aggregate, struggle to outperform relevant indexes after fees are considered. High profile hedge funds are closed in spectacular fashion and, from time to time, malfeasance is reported. The news reports on someone who has been relieved of their life savings by a smooth talker in a suit.

Outrage. The proposed solution: more skin in the game by fund managers.

Some believe that the activities of fund managers could be better aligned to clients via arrangements where a fund manager shares significantly in the outcomes of their efforts. At present, these performance based fee arrangements consist of a low base fee and a performance component which generally rises if they secure favourable returns against an agreed hurdle or benchmark.

One respected asset consultant, Mercer (my fondly remembered alma mater), has gone one step further. They have stirred debate by putting forward the idea that fund managers might be expected to pay money to clients in the event of underperformance. They believe that active management might benefit from increased Darwinism where underperforming fund managers are more rapidly ushered from the sector due to the increased financial pressure.

Mercer does not claim that these ideas are the perfect model. They have aired these ideas to generate productive discussion. They certainly hooked me.

Punitive Damages

The key innovation being proposed is that managers should pay clients in the event that performance expectations are not met. Whilst we can take many perspectives on this, the most obvious is that of punishment. It is proposed that managers should be punished if they harm their clients by way of underperformance. I will call these, collectively, ‘Punitive Fee Arrangements’ (PFAs).

Improving outcomes with more skin in the game

In a recent presentation on this topic, Mercer made an entertaining reference to the Code of Hammurabi. These were a set of laws from Babylonian times which, amongst other things, required that builders were punished by death if the houses they built collapsed and killed the occupants. The ultimate in PFAs.

In something like home building, where solid craftsmanship clearly and reliably transfers to a desired outcome, I think the Babylonians are on the money. In such circumstances, PFAs do have a significant role to play.

Today, these arrangements are known as warranties. They can be found attached to many goods that are bought and, sometimes, the workmanship associated with installing them.

Should fund managers offer warranties as well?

Punitive Fee Arrangements and their Benefits

Of the various possible proposals for PFAs which Mercer has offered, the most interesting is one is termed Guaranteed Active Management. This is an arrangement whereby a manager ‘rents’ the asset owner’s balance sheet via payment of a fee. This fee would be negotiable but might be something like 25 bps per annum. Apart from making this payment, the manager keeps all of the upside/downside arising from their activities.

In theory, an asset owner whose entire fee arrangements are aligned like this will be guaranteed outperformance against their benchmarks.

This approach has several potential benefits. These include:

- Increased alignment of interests, including asset managers resisting growing assets under management too much;

- Improving alignment of time horizons favoured by asset owners and those of their fund managers. In part, this arises because a fund manager may align their own investment horizon with their ability to generate value;

- Encouragement to raise or return assets as opportunities for outperformance arise or dissipate; and

- Risk sharing may help to rebuild trust in the savings industry.

Other variants of PFAs generally have a smaller degree of performance participation, generally 5% to 25%. They generally include a zero or subsistence level base fee and a degree of participation in performance losses.

Given we are exploring PFAs, let us focus our discussion on the purest form – the Guaranteed Active Management arrangement. Readers may form their own judgments about how these might be applicable to more moderate designs.

Punitive Fee Arrangements are Asset Leases

The above arrangement conceives of fund managers bidding for an opportunity to lease balance sheets. Asset owners would be interested in the rents offered and to ensure that the successful bidders are able to support their contractual obligations. Whilst these obligations include the payment of the rent, other matters like avoidance of environmentally controversial investments might be included.

A Guaranteed Active Management arrangement is economically similar to a lease agreement between the asset owner and the fund manager. The asset owner leases the assets to the fund manager and expects to have them returned in good order, together with rent. In this case, the rent is in the form of an agreed benchmark return plus the agreed fee.

Which is the more scarce: Alpha or Assets?

The economic equivalency of PFAs to a lease highlights a perspective that assets are seen to be the scarce resource. Yet, this seems an unusual assertion to make given the enormous growth in financial assets, accompanied with significant increases in leverage. Excellent active fund managers often have their stated capacity filled quickly.

I would argue that alpha generation skill is more scarce. This line of thought supports the perspective that truly skilled managers rent out their scarce alpha generating skills to asset owners. This is the current market practice with ad valorem fees on assets under management being the most common arrangement. To the extent that risk sharing occurs, net refunds to clients are uncommon.

Given the amount of effort and expense dedicated to examining the capabilities of fund managers, identifying alpha generators is clearly a difficult task. Finding assets to deploy is much easier by comparison.

This is not to say that funds management services are scarce. The barriers to opening a fund manager are fairly low. Darwinism requires a rich ecosystem to be most effective and low barriers to entry for superior talent should be welcomed.

To the extent that PFAs are suggested because of a perceived need for more client-centric behaviour, imposing it on the basis that essentially implies assets are more scarce than alpha does not appear particularly prospective.

Fund Managers would require more capital to support PFAs

In order to undertake a PFA, fund managers need to have much more capital available to them in order to support the performance warranty. As the potential liabilities are large relative to the expected yet uncertain gains from active management, funds management becomes more of an insurance business. Instead of insuring cars like a general insurer, fund managers would need to insure against their own underperformance.

The capital required to support the PFA warranties is vastly larger than that required to establish or operate a fund manager of similar scale at present. Whilst a capital market exists to raise this capital or to obtain guarantees via other means, this considerably raises the barriers to entry for funds management.

It might be argued that this is desirable and that the best managers would be able to raise this capital. If they were able to do so, it would be an endorsement of their abilities. However, capital providers would need to be confident that they were backing a manager with significant alpha potential.

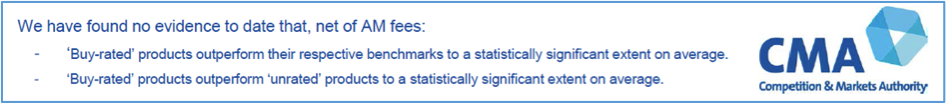

Identifying successful managers ahead of time is difficult. The Competition and Markets Authority in the UK recently conducted an investigation in to the ability of asset consultants to select superior managers. They found some evidence, but it was weak.

If the ability for informed third parties to select successful managers is low, capital raising to support PFAs could be very hard.

Perhaps fund managers could support the warranties themselves? If they are wealthy or already have sufficient existing capital from the outset, it may be possible.

Guaranteed Active Management already exists

There are niche situations where PFAs already exist. These typically arise in situations where an existing insurance organisation has the ability to support performance guarantees. In general, the insurer offers annuities or life insurance related products as the primary activity. However, they are happy to lease additional assets and manage these as proprietary funds to secure greater returns for their equity holders.

So called ‘index-plus’ products are offered where fund managers (or their associated insurance arms) guarantee a margin over an index return. Many different indices are available. The economic form may be a pooled fund or otherwise involve performance swaps in privately negotiated arrangements.

The contractual obligations are often backed with credit support from a parent entity or life insurance statutory fund. The ‘plus’ is usually a fairly small figure, less than 20bps per annum and subject to variation at the manager’s discretion. Additional costs are incurred when asset owners shift assets.

If there were more demand for these arrangements, more supply would probably be created given the available pool of capital within similar structures. The fairly limited take-up of these arrangements to date does suggest that asset owners are happy enough with things as they are. Either that or the insurers, organisations purpose built to accept such risks, are not prepared to pay enough rent to asset owners who believe they can do better on their own.

PFAs and incentives for bad behaviour

Conventional performance based fees are already somewhat controversial. Whilst some see alignment of interest in the arrangement, others see incentive for excessive risk taking. When we also consider the tendency for fund managers to be terminated during periods of weak performance, with limited clawbacks available to investors, it is no wonder that many shy away from these. The Cooper Report (2010) recommended that they be “the exception rather than the rule” and the Hayne Royal Commission is rightfully examining the role of excessive incentive-driven sales activity as a driver behind egregious behaviour that has left many worse for their experience.

If upside risk participation leads to such mixed reviews, adding a downside component does not improve the situation. If PFAs are intended to increase Darwinism, the path way to extinction generally requires passing a threshold of desperation along the way. Desperation is the mirror of greed, and probably the uglier of the two. As a fund manager’s profitability declines, it will be evident to their staff. Though not all will succumb, an arguably rational reaction to an impending loss of a job, and worse, is to increase risk taking activities. Beware the one with nothing left to lose.

PFAs, proprietary trading and carry trades

Trading desks at banks are levied for use of bank capital. Senior traders have strong incentives to secure returns on their capital allocation. Paying a fee for use of assets to secure outperformance puts fund managers into a similar position as proprietary traders.

A natural outcome is for the traders to engage in carry trades. These trades have characteristics of having a high probability of securing modest returns with a small probability of severely negative outcomes. They come in many forms. It is arguable whether the returns to these are actually alpha or a version of smart beta, if even positive over the longer term.

Whilst fund managers can twist internal incentive schemes to deflect some behaviours of this type, ultimately these incentives exist somewhere if a PFA is in place.

An increased utilisation of PFAs may reduce the stability of financial markets as it may encourage managers to utilise correlated carry strategies. The potential contagion effects were demonstrated in the GFC. The build-up of levered carry trades, across multiple points in the financial system, contributed materially to the following turmoil.

Perhaps there is such a thing as too much Darwinism at times, especially if it encourages self-organised criticality like this.

Collective Punishment

Large institutional funds and their advisors are the very well placed to compare the relative merits of fund managers. They generally have good access to senior staff and are well positioned to conduct very thorough examinations of holdings and trades in portfolios.

Sophisticated tools and expertise are available to extract meaning from this information and develop appropriate configurations. Many asset advisors also offer their own fund of funds products. The investment arrangements are highly diversified, with large panels of thoughtfully chosen investment managers.

These are funds management activities. Arguably, the decisions made at this level dwarf the impact that individual fund managers have on client assets.

If industry outcomes are disappointing in some way, surely some responsibility for this resides at this level as well.

Insufficient Predators

In theory, an individual has many options in relation to where to place their investments. However, most individuals select the (implicit) default option. There are exceptions, of course. Some individuals exercise choice regularly but studies into these activities routinely find that value destruction occurs in aggregate.

At the top of the food chain, then, we currently find limited Darwinism. The individual savers do not behave like predators. They do not know how to or are not interested in doing so.

Pillow fighting amongst whales, hammer blows amongst minnows

Poor market function at the level of the end investor increases the importance of counter-balancing measures at the next level. It also underlines the importance of acting as fiduciaries and supports rigorous regulatory activity.

To that end, the large fund-of-fund houses and large asset owners appear to be protected species. The same names appear every year. They just get bigger. Though they compete, it generally isn’t to the death on investment performance grounds. They largely nibble at each other in that regard.

Insufficient competition at this level has been a target for policy investigation, with the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority currently undertaking detailed work on this. It continues to feature in Australian political discourse.

The ideal industry structure for these activities would probably not be to have particularly high levels of creative destruction. However, infrequent changes amongst the (trend adjusted) relative size of the largest funds, together with the relative stability of the market share amongst advisors, highlights that something other than investment returns is driving business outcomes for these entities. These may be distribution power or client inertia amongst other things.

In contrast, fund managers have always made easy targets. Most active fund manager professionals have volatile lives. Even within funds management monoliths, the experience of individual active investment teams within them is often a scramble at the edge of existence. A lack of Darwinism amongst fund management teams is not what I observe.

Active fund managers are already seen to be far too short term in their focus. That arises significantly because their clients judge them on ever-reducing time frames and show a propensity to churn underperformers. If anything, there is probably too much Darwinism on fund manager investment performance already.

Instead of asking fund managers for yet more skin, maybe the balance of risk-taking needs to be re-considered amongst asset owners, their advisors and active fund managers. It would be interesting, for example, to compare the sensitivity of take-home pay to investment performance across different segments of the value chain.

It might be that asset consulting professionals are generally paid too little relative to their fund manager counterparts, given their potential and controllable impact on client assets, but do not have enough skin in their game. If so, there might be a market failure that needs rectifying. Just maybe.

Activity-Based PFAs

Some industry practices certainly did need review. Fee transparency, disclosing costs for research, degree of advocacy for governance, and consideration of climate risks are all examples of positive steps to improve outcomes within the industry in recent years. More aspects for improvement will continue to arise.

As asset owners and advisors avoided fund managers with inadequate practices, an activity-based PFA of sorts is already demonstrably in operation. The market functioned as intended.

Activity-based PFAs, rather than those entirely focused on investment outcomes, may have a valued place in our ecosystem. Fund manager fee negotiations may include fee penalties if some element of their practices do not meet an agreed minimum standard. This might conceivably include features like adequate gender representation amongst professional staff or demonstrable, measurable, advocacy for improved corporate governance practices. These may be a way to communicate and align the values of asset owners with their service providers.

Fund Managers get a bad rap

No fee arrangement will change the fact that the direct aggregate outcome of active fund manager actions is the destruction of value arising from transaction frictions. Reputational damage arising directly from this observation is largely unavoidable. No-one forces investors to use active managers and ETFs are readily and cheaply accessible.

If might be argued that, if the entire market utilised PFAs, asset owners perpetually benefit at the expense of capital providers to active fund managers. True. Now play that thought forward and we find an industry which structurally destroys value for their shareholders. That is not a firm foundation on which to build fiduciaries. PFAs would become unsustainable.

Although public surveys may reveal that fund managers are perceived poorly by the public, we should be careful of these outcomes as drivers for change. Most members of the general public cannot reasonably differentiate activities in the rarefied world of high finance. A CDO-squared proprietary trader at Bear Stearns may not be adequately differentiated from a long-only municipal bond fund manager at BlackRock. They all look the same to someone with a normal life outside of finance.

Larry Fink, BlackRock CEO (left); James Cayne, former Bear Stearns CEO. Does the general public know the difference between their activities?

PFAs on investment returns are not going to change this. As discussed, it might even contribute to worse outcomes.

Conclusion

Activity-based PFAs, as opposed to investment performance based ones, may have a role to play in investment management agreements.

If more Darwinism is required to improve investment outcomes, we should shine the light further up the food chain than the hapless fund manager. Fortunately, the torch lights are on.

References:

Mercer, Oct 2017, “Investment Management Fees: Seeking Fairness and Alignment”

Mercer, Oct 2017, “Rebuilding Trust: Guaranteed Active Management Anyone?”

1 topic