The Arguments Against Austerity are Simplistic and Short Term

The recent debate over austerity has been profoundly one sided. Articles by Paul Krugman, Robert Skidelsky and Ryan Cooper have taken on a victory lap tone for the anti-austerity camp, despite the fact that the race is far from over. Most publications, particularly the economics opinion site Project Syndicate, have given favourable coverage to the anti-austerity camp and have largely refused to entertain the other side of the debate. Yet when both sides of the debate are weighed, it’s clear that those who argue against austerity have simplistic arguments focussed only on short term economic impacts.

I can make a claim like this as I’ve recently taken the time to write to several authors of anti-austerity articles. I’ve laid out responses to their claims, have asked questions of them and have given them the chance to ask questions in return. Through this I’ve gained a better understanding of their thinking and the merits of their arguments. There are some things we agree on and some things we don’t. What stood out most is that there are questions that the anti-austerity camp consistently chooses to ignore. In the three sections that follow I’ve laid out (i) the key arguments anti-austerity advocates make, (ii) the questions they ignore and (iii) the alternatives to current policies. In doing this I hope that readers are given a more balanced view of the arguments and can form their own view of whether austerity is a necessary part of government budgeting.

Arguments from the Anti-Austerity Camp

Austerity Guarantees Sub-Optimal Growth

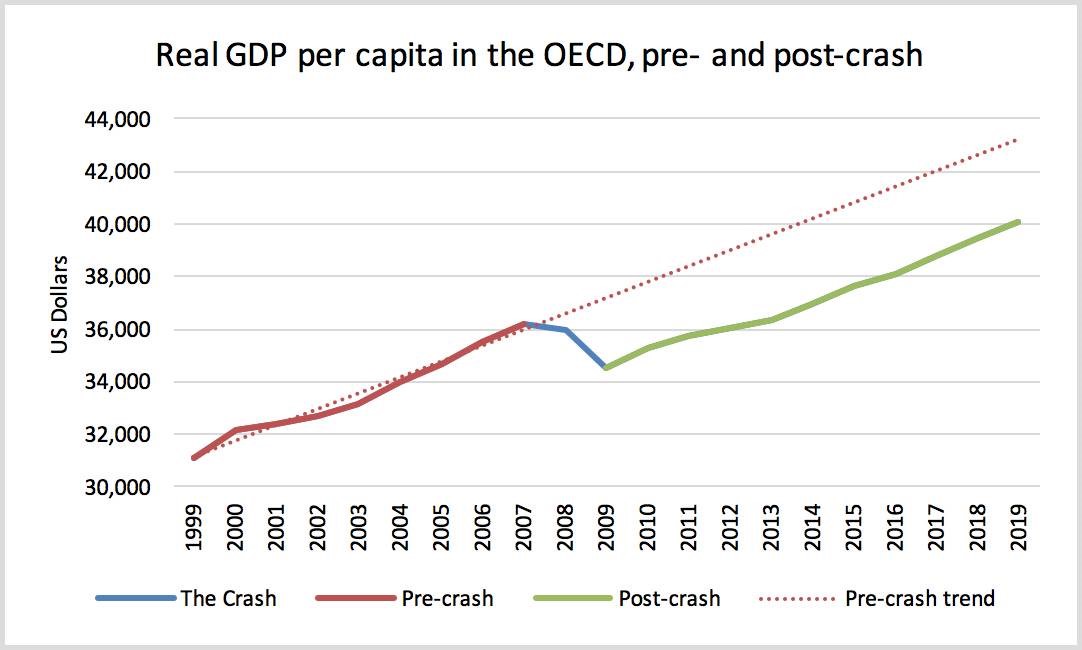

The most common argument against austerity is that GDP growth will be slower without it. At a basic level this is true, stimulus obviously creates short term growth. The graph below from Robert Skidelsky’s Project Syndicate article shows the real GDP per capita for the OECD. After the onset of the financial crisis real GDP per capita fell and took five years to get back to its previous peak. The simplistic argument is that if sufficient stimulus had been provided this slump could have been avoided and trend levels of growth would have continued.

Source: Project Syndicate

This idea of missed growth is a fallacy based on a false starting position. The underlying assumption is that the pre-crisis growth was sustainable. The possibility that debt fuelled spending, whether from government or the private sector, might have inflated growth is never considered. It’s equivalent to arguing that Lance Armstrong would have performed the same if he didn’t use performance enhancing drugs!

Proponents of the missed growth fallacy often also ignore the question of who will fund the stimulus. If only Greece hadn’t been forced to adopt austerity measures then it’s economy would have recovered faster! Should Germany, France and other European nations been forced to fund a bloated and inefficient public sector in Greece? Should other Europeans have to work longer so that Greeks can retire early? Clearly Greece had inflated its growth using debt and there was always going to be a pullback in growth when the pre-crisis stimulus stopped.

Japan Hasn’t Experienced Hyper-Inflation

This is correct, Japan has pushed monetary and fiscal stimulus far beyond what other countries have without dire consequences. However, this isn’t a great example of what other countries could do for two simple reasons; (1) Japan is the world’s largest creditor nation and (2) its citizens are unbelievably loyal in buying their government debt. Few, if any other major economies would be able to push stimulatory policies this far without a collapse in their currency and a collapse in buyers of their debt. Given enough time, even Japanese citizens will realise that a restructuring of its government debt is inevitable and that they are better off buying other assets, predominantly outside of Japan.

Another point on Japan ignored by the anti-austerity camp is why the country hasn’t gotten out of its slump after decades of low interest rates and government deficits. If these policies are so helpful what’s gone wrong? Could it be that Japan needs structural reforms and debt restructuring to rebase its economy and restart growth?

Countries can Grow into their Debt, like the UK did after World War Two

The example of the UK after World War Two is a rare instance of an economy growing into very large debt levels. Some factors that allowed that to happen included:

- Solid population growth

- Low or negative real interest rates

- Latent private sector demand that had been crowded out by economically wasteful war spending

- Very low private sector debt

- Low workforce participation by women

- Positive demographics (low level of dependents to workers)

- 30+ years without a meaningful recession

- Patient and generous creditors

- Real GDP growth averaging around 3%

- Inflation averaging about 5%

- Increasing education levels

- Limited concern for long term environmental damage

Not many of those factors apply in developed nations today. This argument also ignores the obvious counterfactual; if the debt wasn’t there and repayments were instead available for tax cuts or government investment then GDP would have grown faster than it did. Alternatively, if there had been a debt restructuring and normal monetary policy, growth would been lower for a short period of time and then higher for a much longer period of time.

Questions for the Anti-Austerity Camp

Which Governments can Ignore Debt Levels?

Anti-austerity articles typically encourage broad adoption of ultra-low interest rates, quantitative easing and substantial budget deficits. However, as the examples of Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Turkey, Argentina, Detroit, Puerto Rico, Greece and Weimar Germany show there is clearly a limit to who can adopt these measures. When pushed, the anti-austerity camp will concede that governments without reserve currency status aren’t able to follow their prescription. The small group that meets this criterion includes Japan, Switzerland and the US, and possibly the UK.

This leaves the vast majority of countries, as well as state and local governments in the “subject to debt limits” group. Countries in this group can only borrow as much as lenders trust them to repay and if that trust evaporates they will be forced into austerity measures.

Is Hyper-Inflation Limited to Emerging Markets?

Similar to the question above, there’s an assumption amongst the anti-austerity camp that hyper-inflation can only happen in emerging markets. For this to hold true, investors aren’t rational and/or don’t have the ability to move investments to other jurisdictions. The most obvious proof that this academic argument doesn’t survive contact with the real world is the Target2 balances of Italy and Greece. Citizens of these countries have formed the view that their country is at risk of capital controls and/or abandoning the common currency, which could lead to debt redenomination, defaults, bank failures and likely rapid devaluation and hyper-inflation in the replacement currency. Greece has only been able to stem its outflows by maintaining strict capital controls for three years and counting.

There’s also the possibility of a split amongst developed economies in coming decades. Countries that adopt balanced budgets and positive real interest rates could attract capital away from high deficit and low interest rate countries. For a country to turnaround a currency collapse it needs to regain credibility by raising interest rates and balancing their budget. The continuation of quantitative easing and budget deficits would all but guarantee hyper-inflation.

Will Low Interest Rates be Permanent?

Another subtle assumption that underpins anti-austerity views is that interest rates will remain low for decades. This is obviously not the case in the US now, with their debt servicing costs increasing as debt resets to higher interest rates. Even if global rates were to remain near zero for decades to come there are consequences for that. In the last decade we have seen the artificial inflation of asset prices, malinvestment, zombie companies, growing inequality and credit bubbles due to ultra-low rates and quantitative easing. Existing monetary policy has created the necessary conditions for the next crisis when the damage from the last crisis still hasn’t been resolved.

Do Debt Repayments Reduce Future Growth?

This follows on from the previous question, in that whilst interest rates are low debt servicing is low and larger debts are more sustainable. Yet if interest rates are normalised, debt servicing will become a substantial drag on economies. To adopt anti-austerity arguments requires ignorance of the basic economic principal that debt brings consumption forward. The primary argument for austerity is a case of small pain now instead of greater pain later. To meet repayments on accumulated debt in the future, there’s less money to spend on things that would have grown GDP. There’s no free lunch, the spending multiplier applies on both the upside and the downside.

The main exception is investment, where future returns are greater than the repayment burden. However, only a very small portion of government and personal spending meets this definition, the vast majority can be classified as temporary discretionary spending. It is this form of spending that governments should be reducing now that the global economy is in the recovery phase.

Do you Consider Private Sector Debt?

In the lead up to the financial crisis, government debt to GDP levels were flat in many countries as government deficits were in line with GDP growth. However, corporate and consumer debt levels were rapidly growing. When the crisis struck consumer and corporate debt fell for a few years, but this was more than replaced by growth in government debt levels. We now have a situation where in the next crisis neither government or the private sector has much capacity left for additional debt. If both groups are looking to cut spending and pay down debt at the same time it creates the potential that the next downturn is worse than the last financial crisis.

Alternatives to Current Policies

After considering the above arguments, it is logical to conclude that ultra-low interest rates, quantitative easing and ongoing budget deficits aren’t sustainable in the long term. The fallacy that inflated economic growth levels can be sustained must be corrected. Excessive debt levels must be reduced. There is no easy way to do this, it is a choice between a faster and deeper reset like Iceland or decades of stagnation like Japan.

Monetary Policy

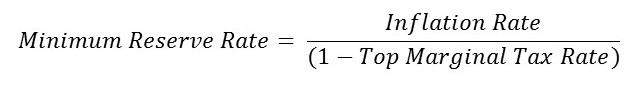

The concept of inflation targeting by central banks is prudent, but the existing settings are based on a false fear of deflation. There is no material evidence that low inflation or small levels of deflation are a problem. Rather, the damage done by setting interest rates too low is obvious and substantial. Financial repression, that is the theft from savers to enrich borrowers and governments, must end. Central banks should be required to ensure that the reserve rate allows all citizens and businesses to receive a positive real rate of return after tax. This can be expressed as:

Similarly, quantitative easing must end. If governments are unable to find lenders at a rate that they are comfortable with they need to deal with their existing debt levels and budget position. Governments will be much better off if they accept that buying their own debt is not a long term solution. You cannot fool all of the lenders, all of the time.

Fiscal Policy

At the very least, governments should return to standard Keynesian economics of deficits in the downturns and surpluses in normal times. The modern monetary theory (MMT) delusion of unlimited deficits has been tried many times and it always leads to debt defaults and/or hyperinflation in the long term. Returning to normal fiscal policy may lead to short-term recessions and/or extended periods of low growth whilst inflated GDP levels are corrected.

Debt Levels

Implementation of the recommended monetary and fiscal policies will expose some governments as having excessive levels of debt. This will need to be corrected through debt restructurings, where lenders lose their claim to some of the principal owed. Iceland’s blunt dealings with international creditors of its banks are a good template to follow. The restructuring of Greece’s debt in 2012 and Detroit’s debt in 2014 both show that without deep reductions to debt levels, accompanied by prudent fiscal management and structural reforms, growth will not return.

4 topics