The longer-term legacy of coronavirus – 9 implications for investors

The magnitude of the coronavirus shock means it will have implications beyond those associated with its short-term economic disruption. Possibly a bit like a world war – where the post war period is very different to the pre-war period.

Of course, coronavirus has not yet released its grip as its resurgence in Europe and the US highlights - with a very high risk of the same elsewhere. But there is good reason for optimism - vaccines are 85-95% effective in preventing serious illness and there are now several effective treatments that are useful for those for whom the vaccines are less effective and for the unvaccinated. Vaccines are less effective though in preventing infection (at 60-80%) and their efficacy fades after about five months – so when 70% or less of the population is vaccinated (as in Europe and the US) that still leaves a high proportion of the population who can get sick and overwhelm the hospital system, particularly as colder weather sets in and efficacy wanes resulting in the return of restrictions in some places. And vaccination rates remain low in poor countries running the risk of new waves and mutations. The only way to avoid this is to get vaccination rates to very high levels (with the help of vaccine mandates), quickly roll out booster shots and only remove restrictions gradually. This includes Australia too.

But the key is that vaccines and new treatments provide a path out of the pandemic and long hard lockdowns and as a result it’s likely that 2022 will be the year we will “learn to live with covid” and it goes from being an epidemic to being endemic. So it makes sense to have a look at what its longer term legacy may be (beyond the associated medical advances that have been big). Here are 9 key medium to longer term impacts.

Bigger government and bigger public debt

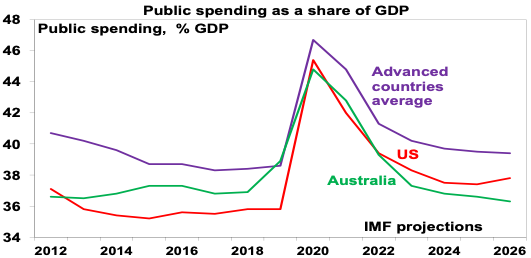

The GFC brought an end to support for economic rationalism and was associated with a leg up in public debt levels. Fading memories of the problems of too much government intervention in the 1970s added to this. The coronavirus crisis has added to support for bigger government intervention in economies and the tolerance of higher levels of public debt. Particularly given that the pandemic has enhanced perceptions of inequality and that governments should do more to boost infrastructure spending and bring production of key goods back onshore. And it’s now combining with a desire for governments to pick and subsidise climate “winners” rather than rely on a carbon price to achieve net zero emissions. IMF projections for government spending in advanced countries show it settling 1% of GDP higher in five years’ time than pre-covid levels.

Source: IMF, AMP Capital

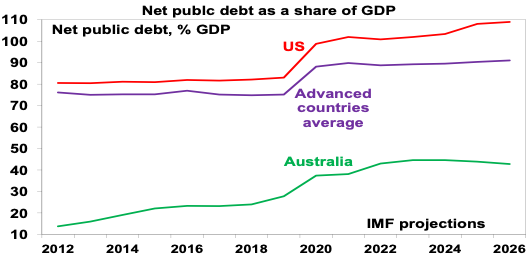

And net public debt is also expected to settle at levels around 15% of GDP higher – more so in the US.

Source: IMF, AMP Capital

Increased money supply and excess saving

The combination of quantitative easing (which saw money injected into economies) along with government spending through the pandemic to support household and corporate income boosted broad money supply measures (like M2 and M3 – which include bank deposits) well above their long-term trend. This is evident in excess household savings (savings above their long-term trend built up through the last two years) of $US2.3 trillion in the US (10% of GDP) and $180bn in Australia (8% of Australian GDP). This is radically different to the post GFC period that saw QE boost narrow money (mainly bank reserves) but was offset by fiscal austerity.

Implications – the pool of excess saving provides a boost to spending a potential disincentive to work (until it runs out) and with increased money supply risks an ongoing boost to inflation, beyond the pandemic driven boost currently being seen.

Increased geopolitical tensions

Geopolitical tensions were on the rise prior to the pandemic with the relative decline of the US and faith in liberal democracies waning from the time of the GFC. This has seen various regional powers flex their muscles – Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia and notably China, which was facilitated by its own economic rise. The pandemic inflamed US/China tensions, particularly over the origin of coronavirus and as the US’ poor handling of coronavirus reinforced China’s shift away from economic liberalism. Russia and Iran are now seeking to take advantage of the global energy shortage, which itself is partly pandemic-related. The summit between President’s Xi and Biden offers hope for a thaw in tensions but it’s not clear how far that will go.

The pandemic has also arguably inflamed political polarisation – with the hard left tending to support lockdowns and vaccines and the hard right against them. This is perhaps more of an issue in the US and parts of Europe than in Australia.

Implications – increased geopolitical tensions could act as a negative for growth, work against multinationals and be negative for shares. It also poses a threat to Australia - with restrictions on imports of various products into China – so far this has been masked by first higher iron ore prices and then higher energy prices. And more political polarisation risks policy gridlock. Fortunately, it’s not as much of an issue in Australia.

Reduced globalisation

A backlash against globalisation became evident last decade in the rise of Trump, Brexit and populist leaders. The coronavirus disruption has added to this. Worries about the supply of critical items have led to pressure for onshoring of production.

Implications – Reduced globalisation risks leading to reduced growth potential for the emerging world generally. Longer term it could reduce productivity if supply chains are managed on other than economic grounds and will remove a key source of disinflationary pressure from the global economy.

Digital world

Working from home and border closures have dramatically accelerated the move to a digital world. Workers, consumers, businesses, schools, universities, health professionals, young and old have been forced to embrace new online ways of doing things. Many have now embraced on-line retail, working from home and virtual meetings. It may be argued that this fuller embrace of technology beyond Netflix will enable the full productivity enhancing potential of technology to be unleashed.

Implications – there are big ongoing implications from this:

- Pressure on traditional retail/retail property has intensified.

- The decline of the office – some sort of happy medium (for example, 2 days in and 3 days at home) will likely be arrived at trading the need for collaboration and team building against the need for quiet time and getting things done. But it has huge implications for office space demand and CBDs.

- An ongoing reinvigoration of economic life in suburbs and regions – as work from home continues (albeit not necessarily for five days for all).

- Virtual meetings may see less demand for business travel.

Greater lifestyle focus and the “Great Resignation”

It’s conceivable that the lockdowns have driven many to rethink what’s important in life and that pent up saving through the pandemic along with the ability of many to work from home has provided flexibility for some to refocus and a reluctance to the fully return to the old grind. In fact, the term “Great Resignation” has been coined in the US as labour force participation remains below pre pandemic levels and the proportion of workers “quitting” their jobs is at record levels. This in turn (and the absence of skilled immigrants and backpackers in Australia) may be contributing to labour shortages (which given the boost the pandemic provided to goods demand has created supply shortages and a surge in inflation). Of course, some of this may fade as excess savings are run down, people return to work as the pandemic fades and there is less evidence to support a “Great Resignation” in Australia where jobs turnover is normal. And it seems like only yesterday there was talk of automation wiping out lots of jobs – so it could all just be another beat up. Then again, it's likely some of it will linger as work from home has shown a way to a higher quality lifestyle.

Implications – this will provide an ongoing boost to relative demand for lifestyle property, albeit it risks driving higher wages in the short term. And labour supply in some countries may take a while to get back to what it used to be.

A post pandemic boom?

It’s conceivable that elation once the pandemic is finally over, the spending of pent up demand and excess savings along with the productivity enhancing benefits of new technology unleashed by the lockdowns will drive a re-run of the “Roaring Twenties” much like occurred after Spanish flu. Time will tell.

Implications – growth may turn out stronger than expected.

More Europe

Each new crisis seems to bring Europe closer together. The ECB’s response to the pandemic which has seen it buy more bonds in problem countries and the economic recovery fund where Italy and Spain will receive a disproportionate share highlight that Europe is getting closer and the impending change of government in Germany may add to this. The pressures to keep the Eurozone together (safety in numbers, a high identification as Europeans, support for the Euro, Germany benefitting from the EU and Germany’s exposure to Italian bonds via the ECB) remain stronger than the forces pulling it apart.

Implications – I still wouldn’t bet on the Euro breaking apart.

A smaller Australia?

Given the hit to immigration by 2026 Australia will be 1 million people smaller than expected pre coronavirus. And the Federal Government appears to have rejected the idea of a catch up in immigration levels to make up for lost arrivals.

Implications – the hit to immigration if sustained could mean a more balanced housing market in the years ahead with less upwards pressure on prices and reduced potential growth in the economy as a result of skilled shortages and lower population growth. But of course, this could reverse if the Government rapidly ramps up immigration after next year’s Federal election.

Concluding comments

Some of these implications will constrain growth and hence investor returns – bigger government, reduced globalisation, lower population in Australia and a possible longer-term threat to labour supply. And increased geopolitical tensions could add to volatility. Against this, the faster embrace of technology boosting productivity and a potential post pandemic boom will work the other way and is positive for growth assets.

The biggest risk is high inflation. Just as World War 2 and expansionary post-war policy ultimately broke the back of 1930s deflation, so to the pandemic and its monetary and fiscal response is likely to have broken the back of the prior disinflationary period. This in turn means the tailwind of falling inflation and interest rates which provided a positive reflation and revaluation boost to growth assets is likely behind us.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

5 topics