Are we heading into a golden age?

The value of gold companies with their primary listing on the ASX has surged from $45bn at the start of 2024 to $146bn today.

This is excluding Newcrest Mining, which was previously Australia’s largest listed gold company but was taken over by Newmont Corporation in late 2023, whose market capitalisation has increased from $70bn to $165bn over this time.

There are now nine gold companies listed on the ASX with a market capitalisation of greater than $5bn, which is up from two at the end of 2023. All of these companies, many of which are not household names, now have a market capitalisation exceeding that of companies such as Penfolds owner Treasury Wines, regional lender Bank of Queensland and global industrial and medical glove manufacturer Ansell. And all of this is a function of a rapidly rising gold price.

The move in the gold price has been extraordinary. It has recently gained US$1000 (32%) in less than 2 months and US$2,500 (141%) in the last two years. Since the end of 2015 the gold price has gained over 318% to its recent peak of $4,381.

The question is whether the gold price can continue rising, or whether the laws of demand and supply will ensure a reversal. In an attempt to answer this question, we have analysed the demand and supply dynamics in the gold market.

Demand For Gold

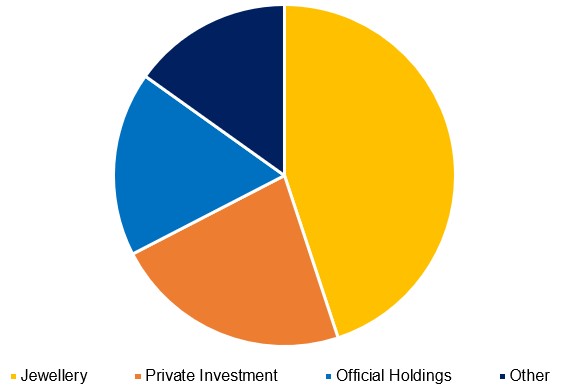

Historically the demand for gold has been primarily for jewellery, representing an estimated 45% of total above ground stocks in 2024. Private investment in gold represented 22% of the gold stock and official holdings by central banks were 17%.

Gold Stock by category

Source: World Gold Council, Auscap

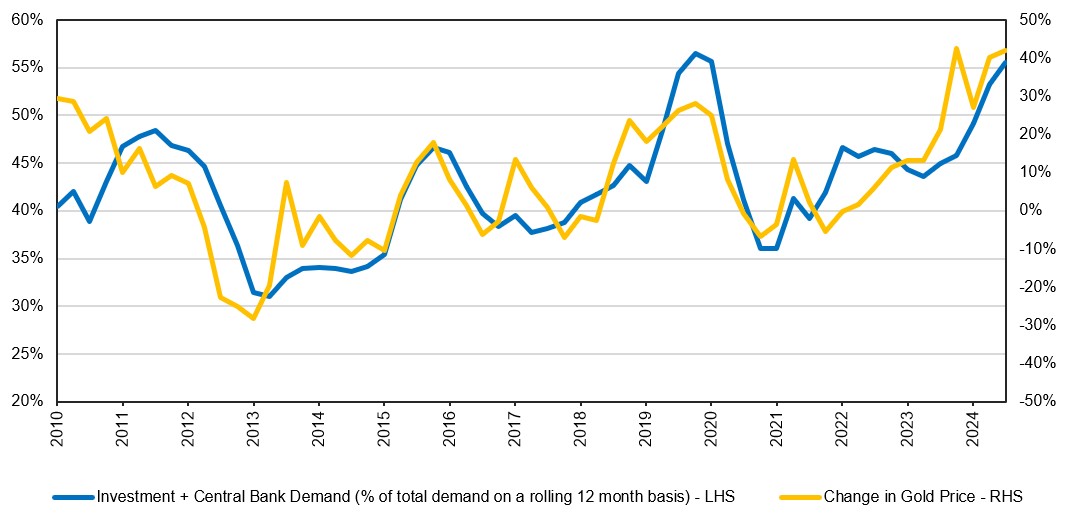

However, it appears that incremental demand is being driven by central bank and investor buying. Purchases for the use of gold in jewellery and technology have declined as a percentage of aggregate demand in recent years.

Over 60% of demand in the first half of calendar year 2025 was for investment, compared to an average of 42% between 2010 and 2023. There is a strong correlation between the percentage of total gold demand driven by private investment plus central bank demand and the gold price, as demonstrated in the chart below.

Investment Demand for Gold vs Gold Price

Source: World Gold Council, Bloomberg, Auscap

There are multiple reasons given for central bank and investor demand, including diversifying away from the USD, a hedge against inflation, a hedge against other asset classes and USD weakness to name but a few. We find this demand very difficult, if not impossible, to predict.

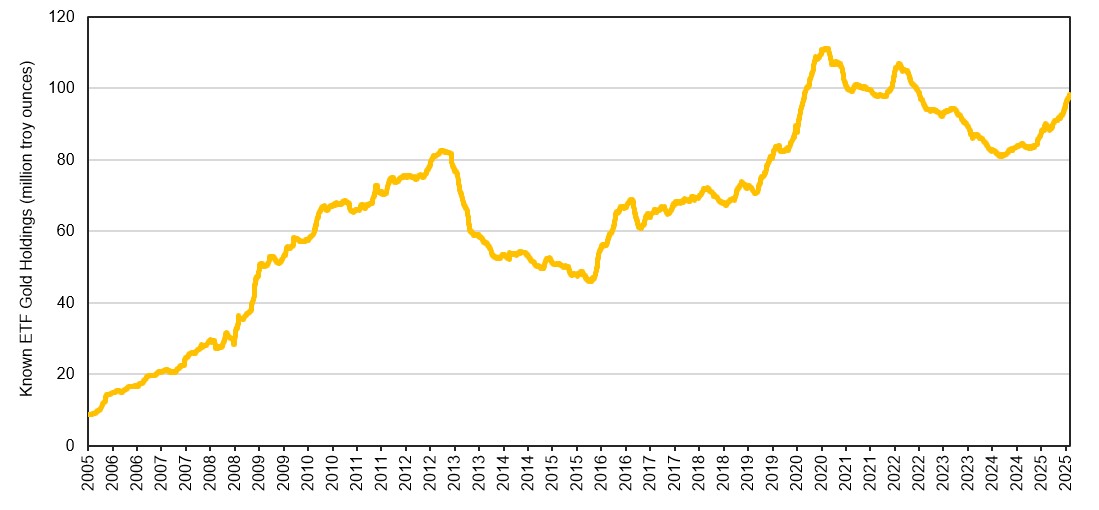

We can see that inflows into gold ETFs are surging, albeit somewhat incredibly they are not at all-time highs. Known gold ETF holdings are still 11.7% below their October 2020 peak.

Gold Exchange Traded Fund Holdings

Source: Bloomberg, Auscap

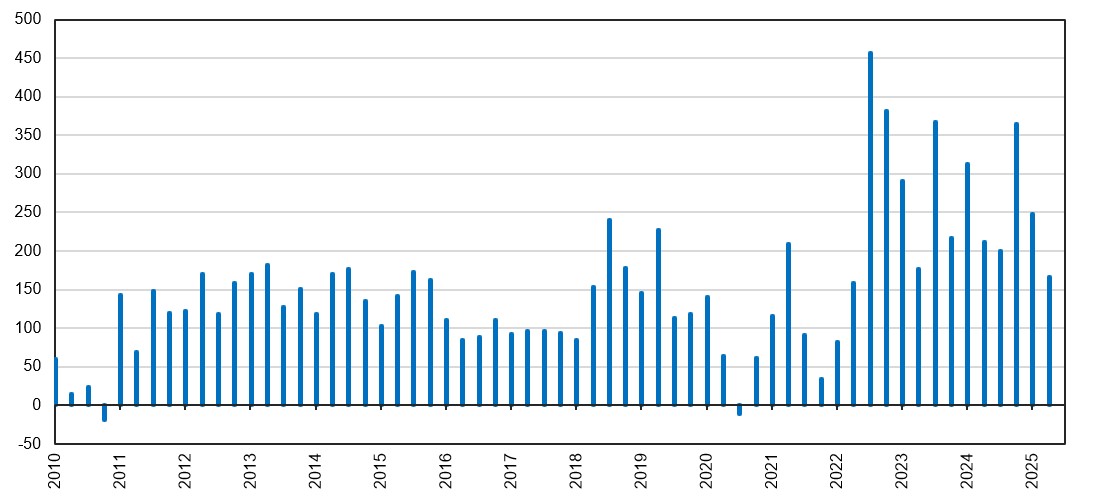

Central bank actions are opaque, less reliably reported and more difficult to make observations on. However, it would appear that central banks have been net buyers of gold since the Global Financial Crisis, as demonstrated in the chart below. The data is not reliable enough to draw meaningful conclusions around recent activity.

Central Bank Demand for Gold (tonnes per quarter)

Supply of Gold

The supply side also has unusual characteristics that differentiates gold from most other commodities. Most commodities are consumed in their application. So a big move in price, as we have seen in gold, would result in a surge in supply. This normally moves a commodity market back into balance or even oversupply, causing a correction in prices. We saw this in the lithium market in recent years.

The gold market is a little different because most of the gold that has ever been mined is still in circulation. Gold is virtually indestructible, so this pool of gold continues to exist in one form or another. In fact, the entire volume of gold mined through history would fit into a single cube measuring 22 metres on each side[1].

Over the last ten years gold mining has only added approximately 1.8% to the global stock of gold annually. So the move in the gold price will certainly result in a surge in gold production, but even if global production doubles this will take the annual increase in gold from less than 2% to less than 4% of the global stock.

You are only likely to see a less than 2% increase in the global pool of gold. Past purchasers of gold can add to the supply of gold if they sell existing holdings, as witnessed by central banks on a number of occasions in the chart above.

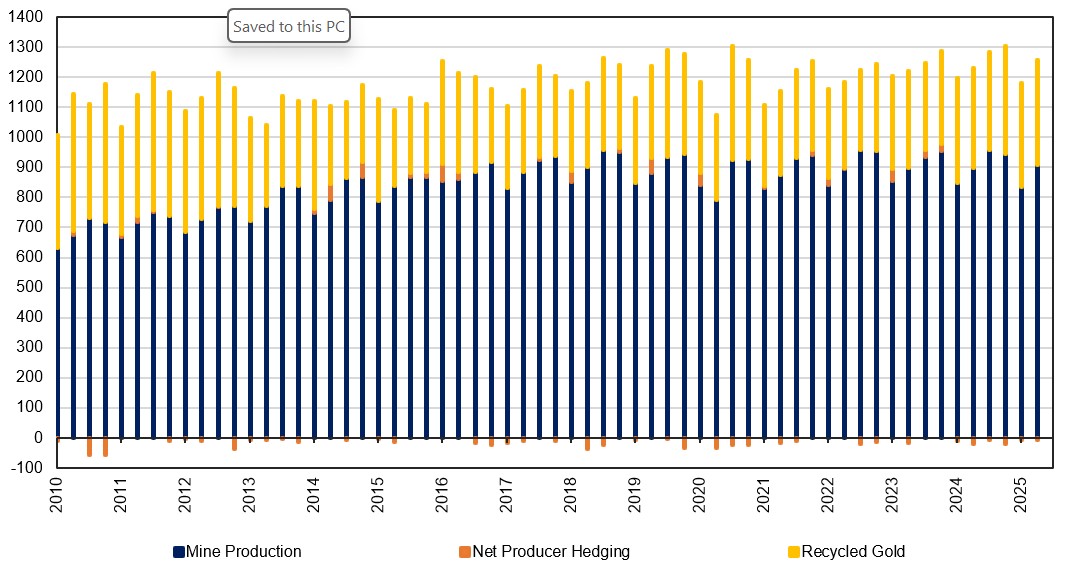

The transfer of existing gold stock between investors and other participants is not captured below. Recycled gold has accounted for 27% of the global annual supply of gold over the last 15 years.

Global Gold Supply (tonnes per quarter)

Fundamental Outlook

There is the potential for the gold price to stay elevated for longer than other commodities might following such a move, because new supply is unlikely to overwhelm aggregate demand as it would in a market where the commodity is being consumed.

Given the complicated demand and supply paradigm, and the significant swings in the demand-supply dynamic caused by fluctuating investment demand, we do not think there is a reliable way of knowing whether this move in the gold price continues.

If central bank and investor demand for gold remains strong, ceteris paribus the gold price has the potential to remain at elevated levels or push higher. Of course, the converse is also true. The likely outcome seems unknowable.

The Real Winners

The real winners from a gold price trading above $4000 an ounce should be the gold companies. This comes with the caveat that this assumption holds true as long as the gold companies can keep their cost inflation in check.

Cost inflation in the gold sector has been notable in recent years, reducing the economic leverage investors experience. However, some inflation in the cost per ounce of production is justified and should be expected.

The current gold price makes many previously uneconomic ore bodies economic and so demand for the same pool of labour, across geologists, engineers, mine managers, machine operators, tradesmen and the like, causes wage competition.

Similarly, it takes time to increase the supply of mining equipment such as drill rigs, diggers, excavators and dump trucks. In the short term, competition for these assets leads to cost escalation.

Royalties that are a function of both price and volume also increase on a per ounce basis. Some mined material that would have previously been left unprocessed is now worth processing if any gold miner has excess mill capacity to do so, but the cost of processing lower grade material is higher on a per ounce basis.

So companies might experience cost growth per ounce even if it makes complete sense to now process this lower grade ore. However, many mining companies have historically lost discipline in times of excess, allowing costs to balloon unnecessarily. Those that do keep fiscal discipline tend to be disproportionately rewarded and are better positioned if and when the commodity price turns down.

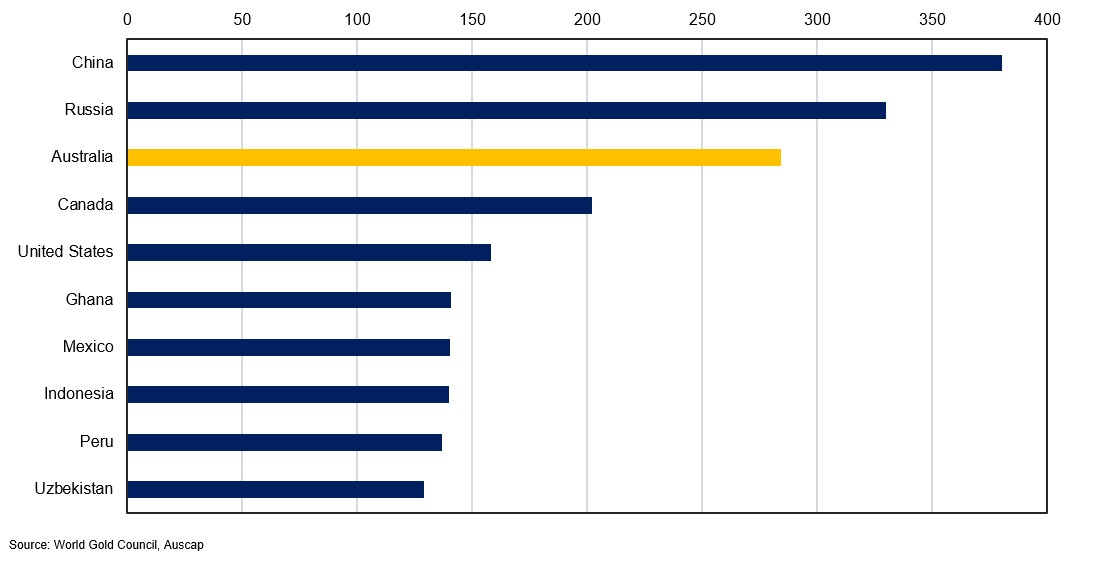

Once again Australia is proving the lucky country. In 2024, Australia was the third largest gold producer with a 7.8% share of global production. We expect domestic production to expand significantly over coming years, with both an expansion in the current operations of existing gold miners and the development of numerous additional gold mines.

The Minerals Council of Australia has suggested that output is anticipated to rise to 369 tonnes in FY27, which would be only marginally below China’s output in 2024.

Gold Production (Tonnes) By Country (2024)

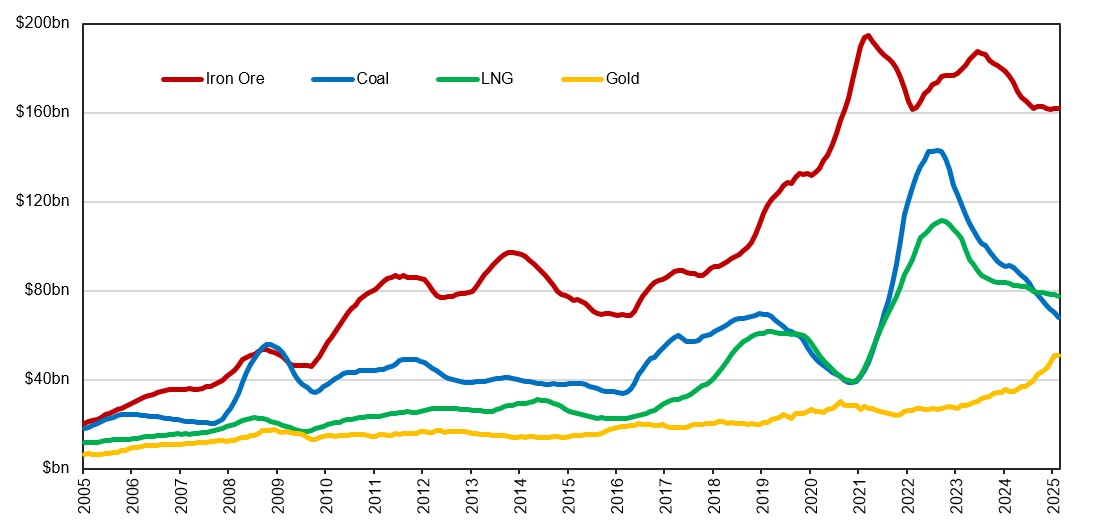

The surge in the gold price is proving a boon for Australia’s terms of trade, with gold at current prices having the potential to surpass both LNG and coal to become Australia’s second largest export behind iron ore. Australia’s fortune in benefitting from almost every commodity boom helps boost Federal and State Government coffers.

Key Australian Exports

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Auscap

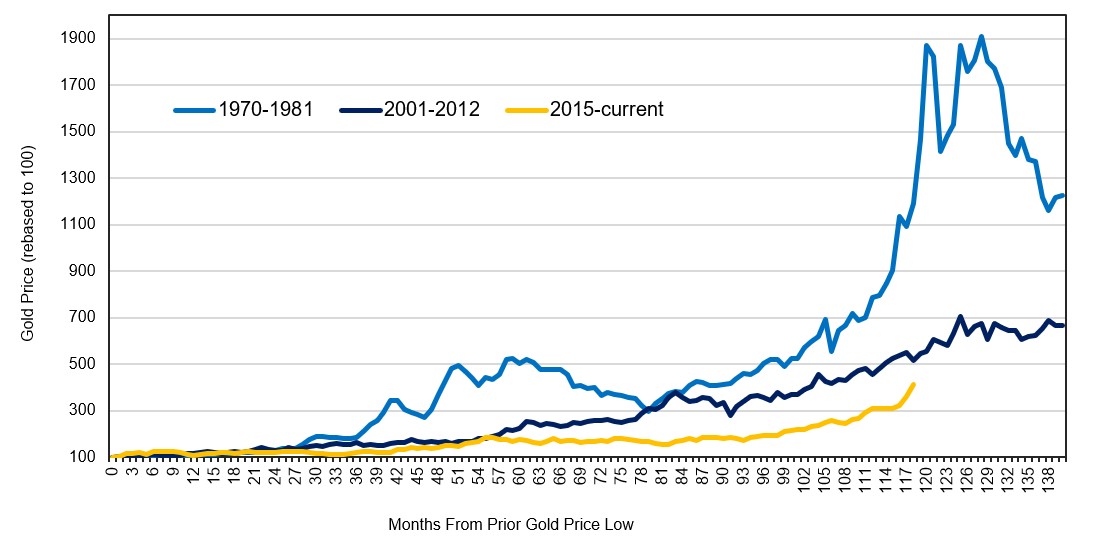

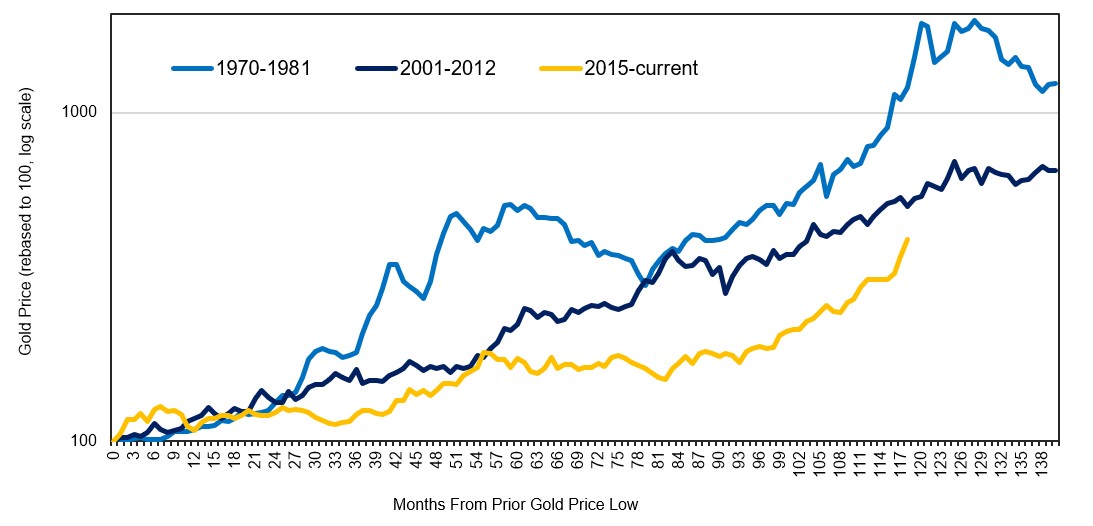

This is the third major gold boom since the dismantling of the Bretton Woods system in 1971, when the price of gold was unpegged from the US dollar at a rate of $35 per ounce. In the 1970s gold gained 19-fold in 10 years.

The next major rally occurred from the early 2000s to a peak in 2011. The gold price went up 7-fold in a ten-year period. These price gains dwarf the 4-fold gain in the gold price since 2015, as demonstrated in the chart below.

Major Gold Booms: 1970 to 2025

Source: Bloomberg, Auscap

Moves of this order of magnitude are probably more appropriately assessed on a logarithmic scale, which measures the percentage change rather than the dollar change in the gold price over time.

Major Gold Booms: 1970 to 2025

Either analysis gives the current move greater context. While we are wary of these sorts of comparisons, we are also mindful of the rhyming nature of financial markets through history.

A continued rise in the price of gold cannot be discounted. Should it continue, Australian investors and Australia more broadly should be a significant beneficiary. The current gold price should result in extraordinary profitability for Australian gold miners, very healthy return on capital metrics and strong cash generation.

The Auscap funds own a number of listed gold companies that we view as having higher quality, lower cost mining operations that have advanced production growth options and are governed by strategic and disciplined management teams.

3 topics

2 funds mentioned