Decoding MFN: Implications (and opportunities) for Biotech Investors

The US president's recent “Most Favoured Nation” (MFN) executive order targeting pricing of pharmaceutical products is generating uncertainty in the market and creating an overhang on biotech stocks. However, despite the noise around MFN pricing, we remain confident that there is no reason to panic – we believe that there is a low probability of full MFN implementation, and the currently depressed prices are creating compelling buying opportunities.

Why are drug prices higher in the US?

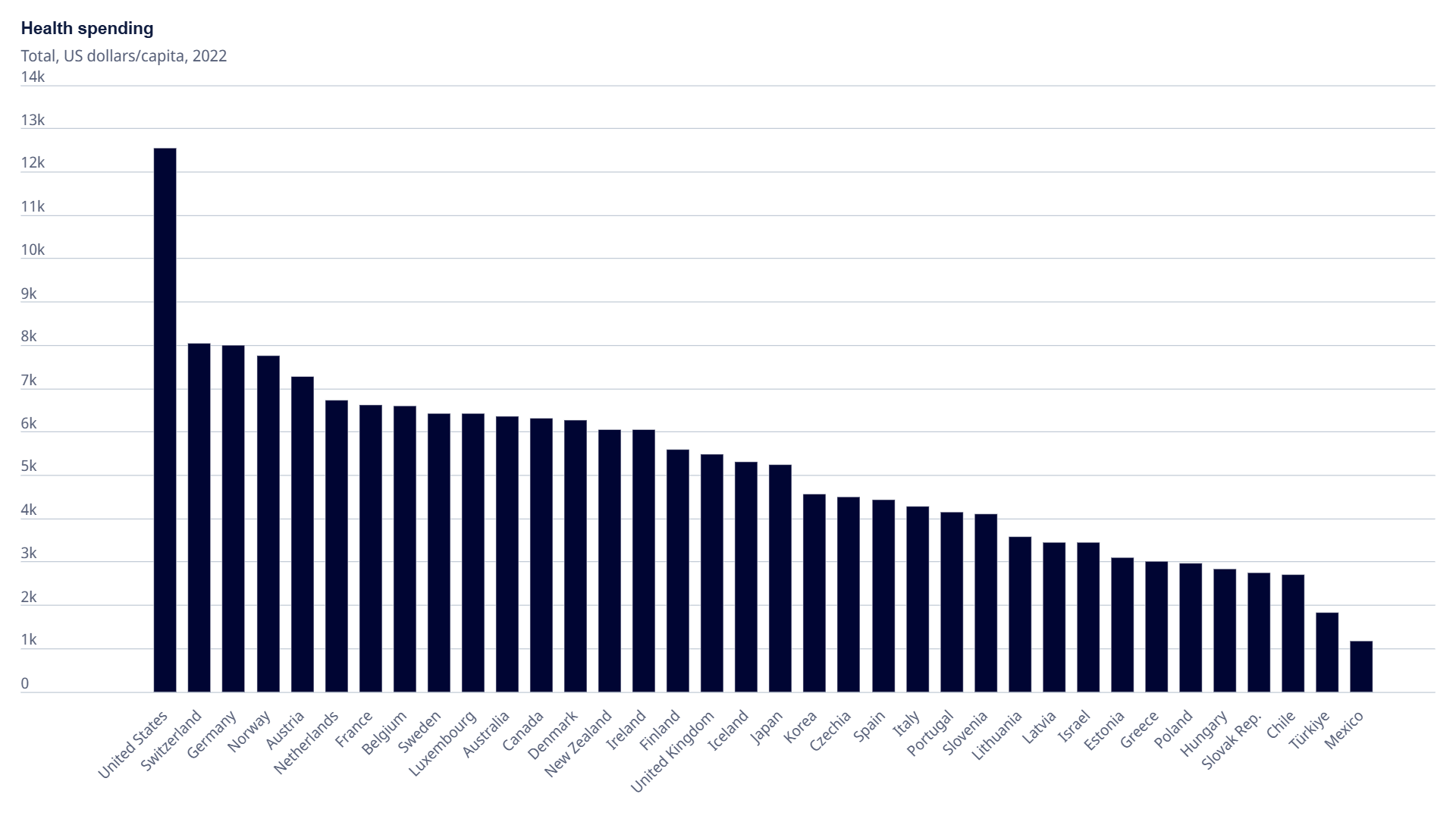

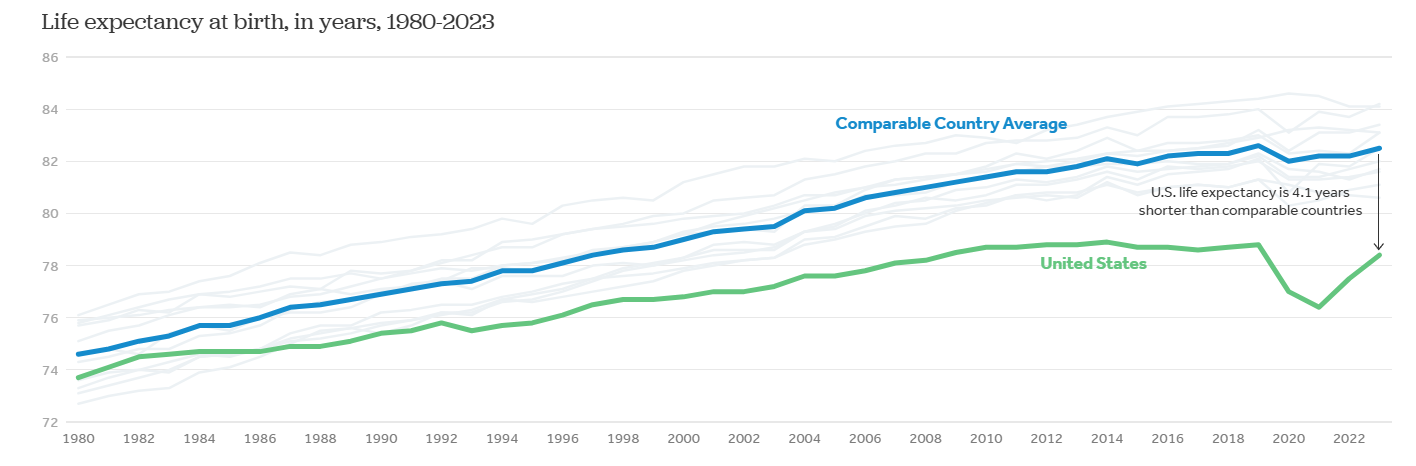

We have some sympathy for the fact that the US has the highest healthcare costs per capita with some of the worst health outcome measures of any OECD nation. Though the US spends over $3700 more per capita than any other high-income nation – $6039 more than the comparable country average – Americans can expect a life 4.1 years shorter than their counterparts. While some attribute this to pharma companies setting high drug prices, higher drug prices are a consequence of the United States’ market-based healthcare system – not the cause.

.png)

.png)

Unlike Australia, the US does not provide universal healthcare coverage. Only 36.3% of Americans are covered by any kind of public plan. The two largest are Medicare and Medicaid, for those over 65 years of age and low-income Americans respectively. The remainder of insured Americans are covered by private plans. This leads to heterogeneous and opaque pricing practices, alongside incentives to charge consumers higher prices.

Consider the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). The PBS can negotiate a single price for medications Australia-wide and subsidises the cost of drugs for Australian consumers by ~90%. In comparison, pricing practices in the US are far less transparent. Pharmaceutical companies set a wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) which is then negotiated by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) who act as middlemen between manufacturers, insurers, and pharmacies. Payors, both public and private, then determine how much the consumer pays for a given medication or service.

To make matters worse in terms of transparency, PBMs, health insurers, and pharmacy chains have become vertically integrated within massive conglomerates in the US. In conjunction with rebates and fees being negotiated privately, there is a conflict of interest at play; PBMs often benefit by increased prescription of costly brand-name drugs. The PBS, on the other hand, can choose to simply not reimburse expensive drugs that offer minimal clinical benefit over the standard of care. These differences, among others, lead to the large difference in healthcare expenses between countries such as Australia and the US.

Ultimately, the US has higher healthcare costs because of the way their healthcare system is structured – not simply because pharmaceutical costs are higher. This is a structural issue that likely cannot be solved with a "MFN silver bullet".

What Is Most Favoured Nation Pricing and How Is It Supposed To Work?

One of the issues with the current MFN executive order is that it contains very little detail into how it is supposed to work to achieve its goals of "lowering drug prices by 30-80% almost immediately." What MFN ends up achieving is likely to be considerably different. To be more blunt, when the MFN executive order was finally released and the market realised there was very little substance contained within, an analyst from TD Securities titled their daily report "Might Find Nothing".

Further clarity is expected to be provided in the coming days, however this is what we currently know:

Under the current proposal, the MFN pricing scheme looks to OECD countries with >60% of US GDP per capita to find the lowest price for a given drug. The US would then align what it is willing to pay for said drug under the “Most Favoured Nation” clause. This is materially similar to Trump’s attempt at MFN in 2020 (which was ultimately unsuccessful).

It should be noted that the proposed MFN pricing functions by lowering the government’s reimbursement rate, not by forcing manufacturers to lower their wholesale prices. While private payors and PBMs would be free to use this in negotiations, pharmaceutical companies would not be obligated to provide the same deal to private payors. This means that such a policy would only directly impact those with public coverage. This is an important point, since under this proposal, it would be the end users who could ultimately end up paying the difference.

Option 1: CMMI Pilot

It also remains uncertain exactly how the program would (or could!) be implemented. One potential pathway to establishing MFN status would be through a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) pilot program. These programs, run by the CMS Innovation Centre (CMMI), don’t require congressional approval, but do face significant obstacles.

CMMI pilots cannot lower quality of care or do harm to patients – if access to Medicare is lowered the policy will be scaled back. One notable example of CMMI limitations comes from a pilot launched by Obama in 2016 which sought to lower the reimbursement for Medicare Part B from average selling price (ASP) plus 6% to ASP plus 2.5% + $16.50. The plan saw enormous pushback from both the medical community and Congress due to concerns over drug access and was dead in the water after nine months.

This is an important precedent for any potential MFN pilot, which would effectively try to lower the actual ASP by >40% in some cases, a much more significant decrease in government reimbursement that the previous ASP+2.5%. As previously mentioned, it is only these government reimbursement rates will be altered by this policy – the price that hospitals and healthcare providers pay would likely remain unchanged.

Considering that many hospitals, particularly the 2,978 Not For Profit hospitals (roughly half the hospitals in the US), typically with thin operating margins, rely on this ASP+6% for funding, reducing the reimbursement rate by 40% could easily push a number of these hospitals into serious financial difficulty, critically impacting patient access and care. Given the CMS mandate to do no harm, it is hard to imagine that this policy would see a fate any different to the previous 2016 ASP +2.5% pilot.

Option 2: Pass Legislation

While a CMMI pilot, despite its limitations, could be conducted unilaterally, implementing MFN through a congressional bill would enable the policy to be far more far-reaching and less open to legal challenges. However, the key issue with this approach is that the proposed plan is required to be passed by congress.

Given that there is division among the Republican Party, with Republican speaker of the house Mike Johnson notably not in favour of MFN, there is little chance such a bill would make it into reconciliation. Probably indicative of MFN's divisive nature within the Republican Party, MFN was not even put forward as part of Trump's "Big Beautiful (tax & spending) Bill" that is currently before the Senate.

It is also worth pointing out that the Biden’s administration's Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a congressional bill passed in 2022 seeking, in part, to lower drug prices, claimed to save billions of dollars on prescription drugs. These claimed savings were calculated on WAC basis, which is almost irrelevant after manufacturers negotiate rebates with PBMs. That is to say, despite the fanfare, the biopharmaceutical industry, and its investors, largely moved on, considering IRA to have a very minor impact. While there is still much uncertainty regarding MFN, we suspect the same will be true here.

Even assuming some form of MFN policy to be implemented, depending on the specific language of the MFN pricing scheme there are numerous potential workarounds for biotech and pharma companies – just because the government lowers its reimbursement price, does not mean the commercial price follows suit.

Potential Reactions from Pharmaceutical Companies to MFN

One thing is for certain – pharmaceutical companies will not take MFN lying down. Almost certainly they will have been formulating a range of strategies to counteract the potential effect of any MFN implementation.

For example, since MFN pricing doesn’t set a specific price but rather seeks to bring US prices in line with the rest of the OECD, one of the easiest strategies available to manufacturers would be to introduce a Gross-to-Net system of rebates, similar to the US. This would enable pharmaceutical companies to raise wholesale prices ex-US to meet that paid by Americans. This could be coupled with indirect reimbursement of administrators and providers, establishing a gross to net bubble that obscures the end price of the drug (as is the case in the US) while keeping the net price similar for consumers outside of the US. This strategy would effectively maintain the global pricing status quo.

Manufacturers could also change the dosing, packaging, formulation, or administration of their drug, making minor changes to impede price matching – if a US drug doesn’t have a clear ex-US analogue, it can’t be lowered in price. A more extreme solution might be to license the rights to the sale of a drug to other companies using a joint venture model.

The companies that may be best positioned to succeed in the face of MFN pricing are those with low ex-US revenues, low Medicare exposure, and low-price differences between the US and the rest of the world. Examples of such companies include Alkermes (NASDAQ: ALKS), Jazz Pharmaceuticals (NASDAQ: JAZZ), and Exelixis (NASDAQ: EXEL), among others. MFN also favours SMID cap companies, who are better positioned to plan for any of these changes prior to their drugs being approved and hitting the market.

MFN Verdict: Creating Investment Opportunities

It’s important to note that whatever the impact, large cap pharmaceutical companies are not going to stop acquiring smaller biotech companies – their business model depends on replenishing their IP on a regular basis, which typically has 10-12 years of life upon approval before Loss of Exclusivity. In fact, despite a slow first quarter of 2025, M&A activity has recently picked up, including the acquisition of one of our portfolio companies, Vigil Neuroscience (Sanofi), continuing our track record of having at least one portfolio company acquired per year. Other recent M&A deals include Regulus Therapeutics (Novartis) and SiteOne (Eli Lilly), however it’s not just small deals, evidenced by Sanofi recently agreeing to acquire Blueprint Medicines for $10b.

While there will inevitably be an overhang in the market while MFN gets resolved, we are confident that MFN pricing is unlikely to materially impact long term asset prices. Moreover, with prices currently depressed, the uncertainty regarding MFN is creating compelling investment opportunities, particularly for selective stock-pickers such as HB Biotechnology.

As we have written before, history doesn't repeat, but it does rhyme. The same principle applies now. While it was inflation that was causing market uncertainly in 2022 and 2023, now tariffs and the prospect of MFN pricing in 2025, we believe that, similar to these past events, the current downturn in prices belies true value and creates opportunities for investors seeking quality companies at discount prices.

4 topics

6 stocks mentioned