Dotcom on steroids

Since the 2008 financial crisis, the US technology sector has been the standout investment trade, defying the concerns of value investors over steep valuations. While many initially underestimated the business quality, growth runway, and long-term earnings power of big tech, these companies—led by visionary founders—evolved into monopolistic giants, delivering fast growth and robust profit margins. In a growth-starved, zero-interest-rate world that continuously drove capital toward secular growing compounders, this was the perfect setup for massive outperformance.

Today, we believe the sector stands at a significant inflection point, with investors seemingly making a one-way bet on the AI mania while appearing to ignore alarming fundamental issues. In our view, the momentum in these growth-oriented segments of the market—including big tech and companies tied to the AI infrastructure buildout—could reverse at any moment. As a result, we have adopted a much more cautious stance toward these investments. We anticipate the next few years for the sector will be defined by deteriorating fundamentals: lower growth, higher competition, and greater capital intensity.

We are not perma-bears on the technology sector; in fact, we were comparatively larger buyers of Nvidia (NASDAQ: NVDA) in 2023, and the stock has been among the top performers since the firm’s June 2016 inception.(1) Clients regularly pushed back on our historical overweight position in the technology sector just a few years ago.

However, our views on the sector have since shifted. Given our goal of capital preservation during downturns and our natural inclination to forgo some upside possibilities in favor of maximizing potential long-term compounding, we would be remiss if we did not raise the question:

How much of your net worth do you want invested in a cyclical sector where many of the largest players appear to be exhibiting growth deceleration, free cash flow margin deterioration, and increasing competition?

This may be worse than the DOTCOM

It may be hard for investors to face the uncomfortable reality that the trade that worked for over a decade may be over. After all, most money managers today do not carry the scars of the dotcom era. Of the approximately 1,700 active large-cap US portfolio managers, just 4% invested through that period.(2) There is a difference between living through a downturn and merely reading about it.

Even the best companies can falter when valuations are stretched and expectations appear exuberant. During the dotcom crash, Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT) and Cisco (NASDAQ: CSCO) lost a third of their value in a matter of a week, and Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN) shed nearly 80% percent of its value over 12 months.(3)

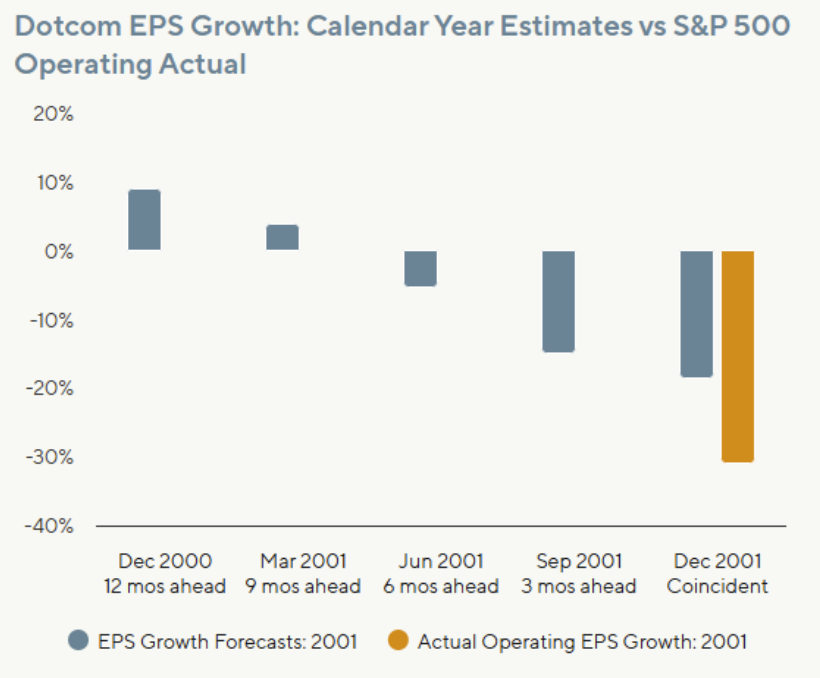

Earnings revisions also tend to be a trailing indicator. For example, in December 2000, several quarters after the peak, analysts were still forecasting nearly 9% earnings growth for 2001. Many leading companies, like Microsoft, continued to grow enviably well in the years following the bubble’s burst. This brings to mind Howard Marks’s view that there are no bad assets, only bad prices. Today feels like an era where bad prices are rampant.

We believe big tech exhibits backward-looking quality

GQG’s investment philosophy is grounded on the idea of “Forward-Looking Quality.” For the first time in our firm’s history, we believe many large technology companies today—particularly those with meaningful roles in the AI infrastructure build-out—represent backward-looking quality.

For much of the last 15 years, investors who compared the exuberant periods in the technology sector to the dotcom era have been repeatedly proven wrong. Is it different this time? We believe so.

In our view, the consequences of the current AI boom could be worse than those of the dotcom era, as its scale—relative to the economy and the market—is far greater.(4,5) Even the AI poster child, Sam Altman, recently admitted we are in an AI bubble, stating: “When bubbles happen, smart people get overexcited about a kernel of truth. Are we in a phase where investors as a whole are overexcited about AI? My opinion is yes.”(6)

Dotcom and today: The similarities

The prior tech bull market was underpinned by two core beliefs, both of which are held today, in our opinion.

1. US Exceptionalism

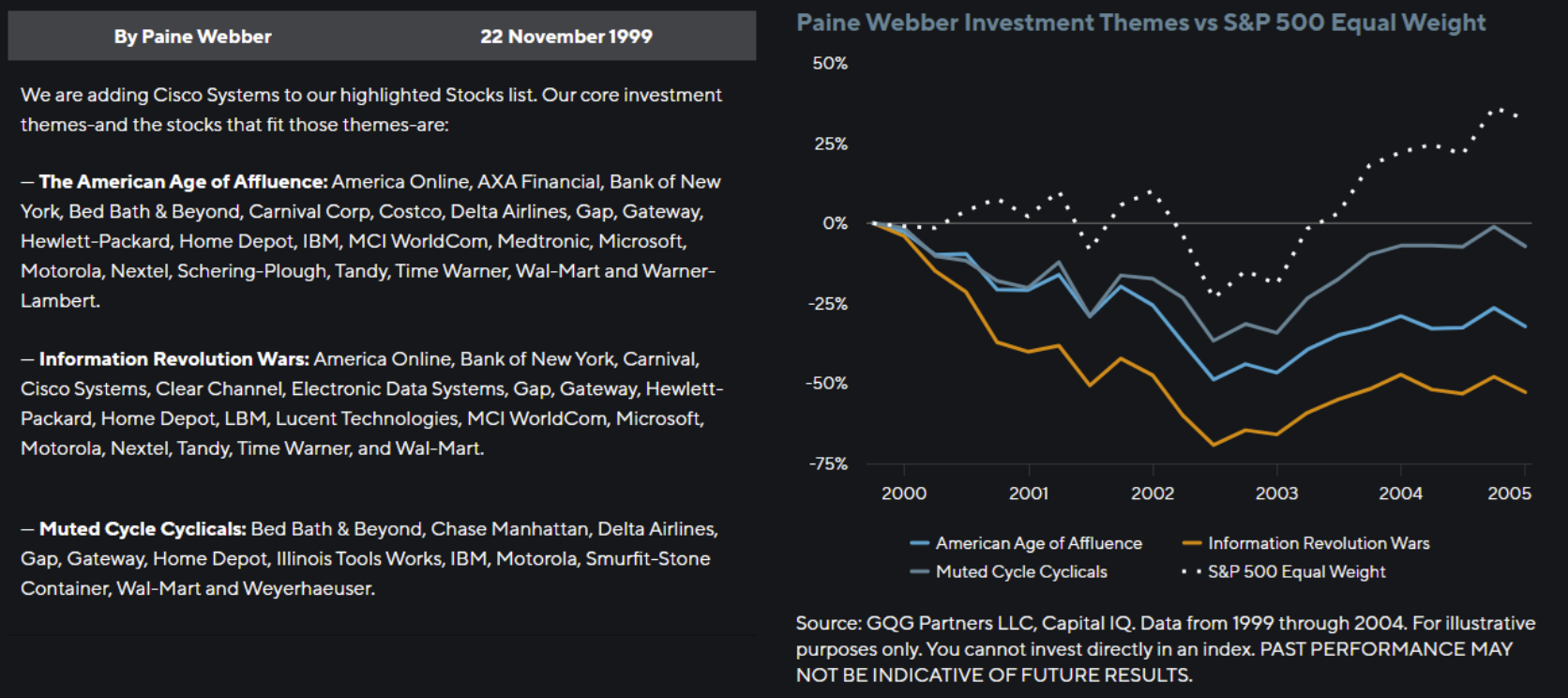

Both the dotcom bubble and today’s AI boom have been fueled by the belief in American economic dominance. In 1999, the US economy was experiencing 5% GDP growth, deregulation, and a booming stock market while other major economies struggled to keep pace. Emerging markets collapsed during the Asian financial crisis, Mexican tequila crisis, and Russian default. Meanwhile, developed markets like Japan and Europe faced sluggish growth. The period became known as the “American Age of Affluence.”

A similar narrative today underpins the AI rally, where the “TINA” (there is no alternative) trade has driven significant capital into US equities.

By Paine Webber 22 November 1999

2. Revolutionary Technology

A key element of prior bubbles is often a new, revolutionary technology that excites both institutional and retail investors. Like AI today, the 1990s gave birth to the internet, a technology that would eventually change the world. Given their fast growth and profitability, Microsoft, Dell (NASDAQ: DELL), and Oracle (NASDAQ: ORCL) were perceived as obvious winners in the late 1990s, thereby justifying their high multiples.

IBM’s (NASDAQ: IBM) comments near the peak of the dotcom bubble capture the prevailing sentiment: “The [internet] revolution has arrived. With stunning speed, it has swept all of us into a new kind of economy and a new kind of society. It’s the first question I get from any IBM customer in almost any part of the world: “What must I do to survive and win in this new world?”…It was a tidal wave, sweeping everything before it.”

We believe this sounds like AI today.

Dotcom and today: The differences and the myths

Most investors can easily understand the above two points, but many quickly push back with the following claims to argue that this time will be different:

- Tech companies today are higher-quality businesses compared to 2000

- Tech companies today are cheaper compared to 2000

- The broader US market today is cheaper compared to 2000

We agree this time the outcome could be different—we believe it could be worse than the dotcom collapse. We also think that some are making an ill-advised bet on the AI boom with their clients’ retirement security on the line.

Misperception #1: Tech companies today are much higher quality than they were in the dotcom era

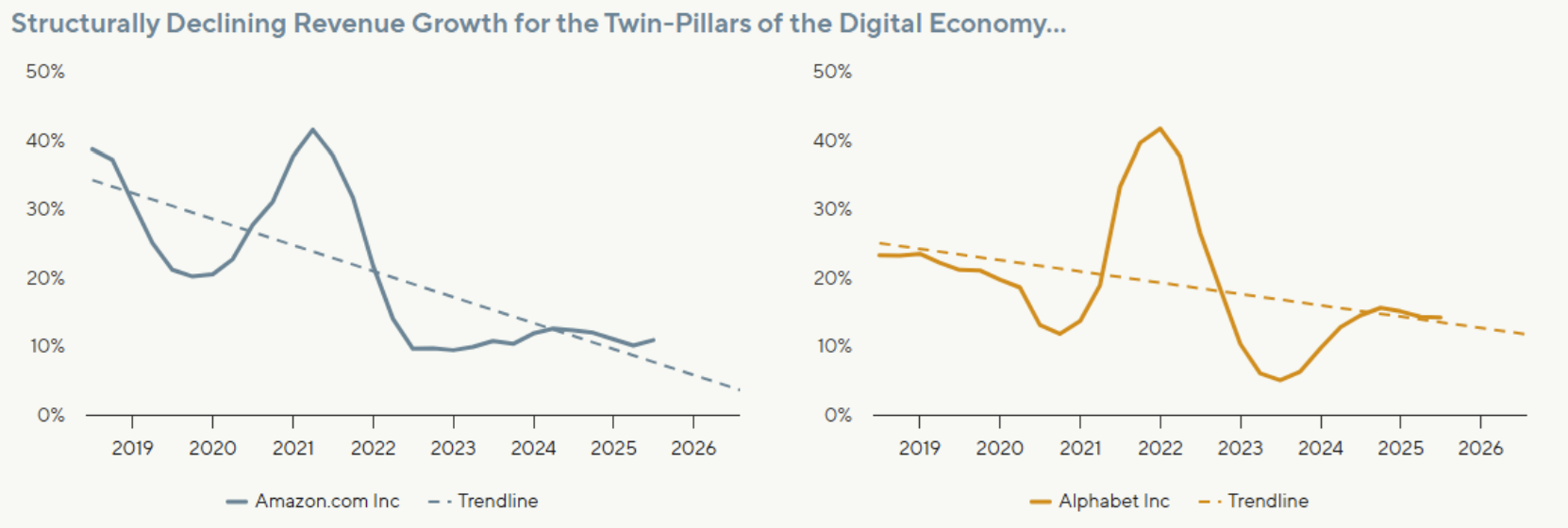

Revenue growth has structurally decelerated

The remaining runway in most technology end markets is an issue, in our view. Once a company becomes the proverbial 800-pound gorilla in its respective sector, sustaining supernormal topline growth tends to be virtually impossible.

How fast can Microsoft or Nvidia grow now that they respectively control approximately 60% of the entire software and semiconductor industry’s profits?

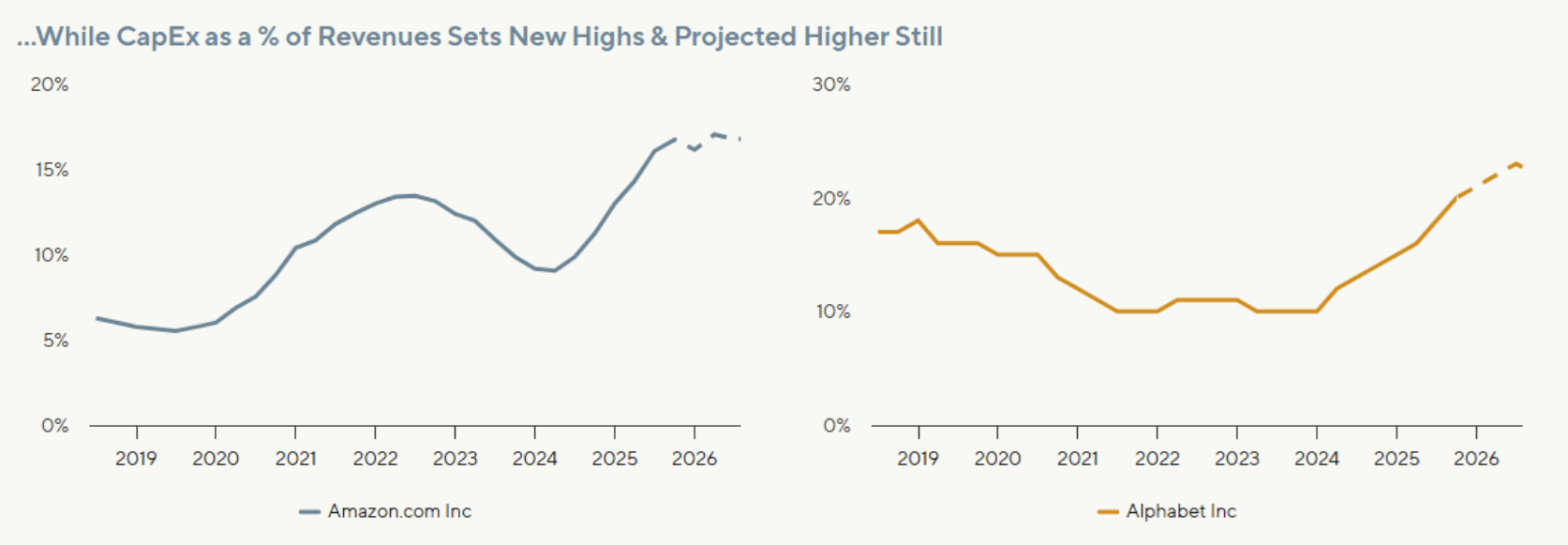

On the current trajectory, we would not be surprised to see long-term revenue growth decelerate to single digits within the next five years. In other words, we believe big tech no longer offers a unique growth profile relative to other sectors. Indeed, a few of these larger spenders like Amazon and Alphabet have been trending in that direction for some time, all the while their capital expenditures as a percentage of sales sets new heights. To be clear, these are names we have owned in the past in a big way—and very well may own in the future when the visibility improves—but at the current juncture we remain cautious.

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data for the time period 30 June 2018 through 31 December 2026. Content does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it. Actual results may differ from any projections illustrated above.

AI CapEx Is Tied to Digital Advertising

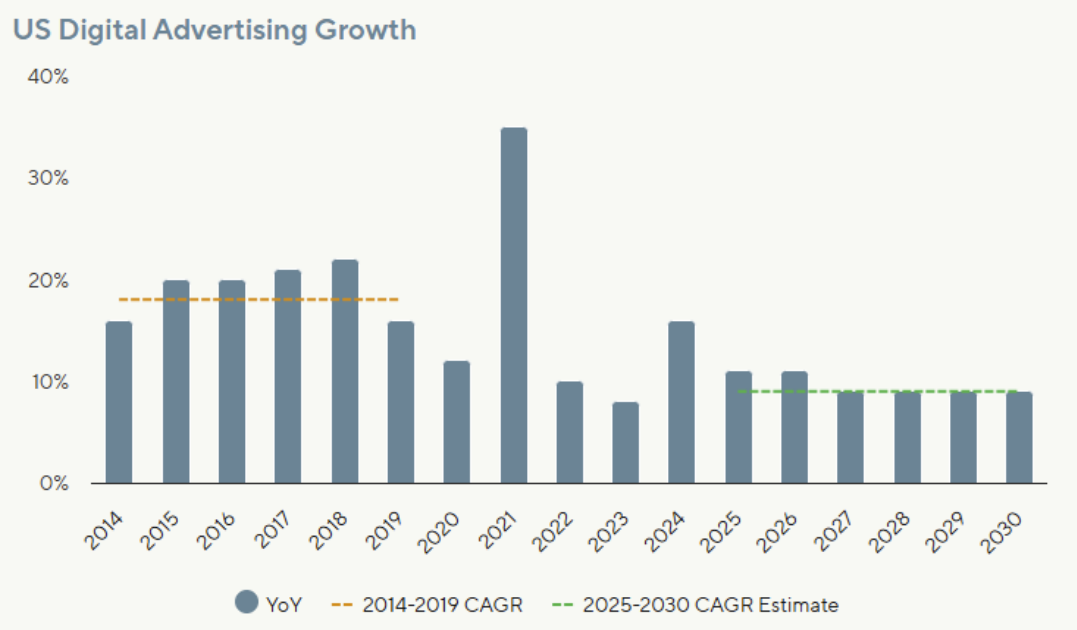

Most of today’s AI capital expenditures are funded by advertising revenue—the lifeblood of Silicon Valley. Digital advertising now accounts for more than 70% of all advertising, so the penetration-driven growth story could be approaching its final innings. Morgan Stanley expects the US digital ad industry to grow at a 9% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2025 to 2030—less than half of its 20% CAGR between 2014 to 2019.

At these rates, we believe the sector may only grow in line with sleepy sectors—think transmission and distribution utilities or property and casualty insurance—yet with considerably higher risk and cyclicality.

Competition has structurally increased

During the 2010s, we viewed big tech as a collection of monopolies: Amazon dominated e-commerce, and Google (NASDAQ: GOOGL) dominated search. Their only competition came from sleepy incumbents ripe for disruption, such as cable television or brick-and-mortar retailers.

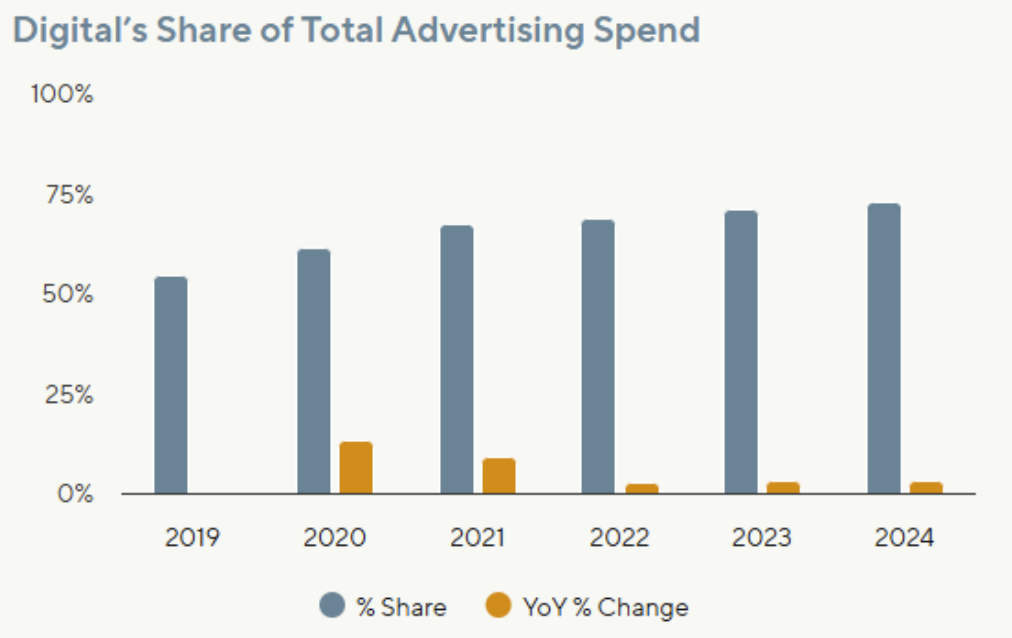

Digital’s Share of Total Advertising Spend

That is no longer the case today. Instead of playing in different sandboxes, big tech has largely converged into the same AI arms race, where they now compete directly against each other.

For example, countless new competitors have entered the digital advertising sector, including Walmart (NASDAQ: WMT), Netflix (NASDAQ: NFLX), and Uber (NASDAQ: UBER). Chinese internet companies have also become fierce global competitors. In fact, ByteDance recently surpassed Meta to become the biggest social network by revenue worldwide.(7)

At the end of the day, ad budgets are finite, and tech companies are increasingly competing against each other—rather than legacy media companies—for incremental growth. Despite massive innovation over the past century, total advertising revenue has remained constant at around 2% of GDP,(8) and we do not believe AI can change this fact. Moreover, there are only 24 hours per day, placing a natural limit on how much each digital platform can monetize users.

Clouds on the horizon

Another great example of the deteriorating competitive landscape is the cloud market, which has been one of the most important growth drivers for several tech giants. This was once a stable three-player market: Microsoft, Amazon, and Alphabet. However, a disruptive fourth player (Oracle) just entered in a big way and is explicitly undercutting peers on pricing by 40%, according to our research.(9) Adding to the shakeup, CoreWeave—a financially constrained fifth player with an arguably more cutting-edge product—has announced its intention to aggressively gain market share through pricing pressure.

Such dynamics have the potential to make life difficult for even the most established players. AWS, for instance, is already showing signs of competitive strain. Its earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT) margins declined by a staggering 7% last quarter, while earnings growth slowed to a pedestrian 9%. That is hardly the picture of robust performance for a stock trading at 30x forward earnings, in our view.(10)

Competition will likely only increase with sovereign cloud players and startups all simultaneously ramping up supply. In fact, China is already experiencing a massive datacenter oversupply, resulting in only 20%-30% utilization rates.11

The cloud market now reminds us of the telecom industry, another highly capital-intensive business. Historically, we have observed that telecom economics typically deteriorate when a fourth player enters the market, particularly if it competes on price. While there are some switching costs with cloud, we do not believe they are insurmountable, as plenty of companies have changed providers in the past. For example, ServiceNow (NASDAQ: NOW) and Salesforce (NASDAQ: CRM) recently signed large deals with Google Cloud, representing a shift away from industry leaders Amazon and Microsoft.(12,13)

It is also unclear how much of the cloud sector’s revenue growth now comes from AI startups, which are typically funded by the same cloud companies. According to one estimate, AI startups spend more than 80% of raised venture capital money on compute resources.(14) If VC funding dries up, a substantial slice of the cloud sector’s incremental spend could be at risk, potentially slowing growth.

This contrasts with the source of the CapEx spent during the telecom era, which came from very profitable, well entrenched regional oligopolies such as AT&T, Verizon (NASDAQ: VZ), and Southwestern Bell, but also names like Deutsche Telekom and China Mobile abroad. In our view, the common narrative of unprofitable start-ups funding growth during that era is just that—a convenient narrative not backed by facts if one examines the sell-side notes from that era. Indeed, we believe today’s CapEx is much more fragile and dependent indirectly on venture capital funding, which has had mediocre returns for a few years now.15 We are not seeing any signs of revenue being generated to keep fueling this spend.

Tech faces substantial disruption risk

In the 2010s, big tech were the disruptors. Today, big tech is the incumbent, while AI is emerging as a highly disruptive force. It is not obvious to us who will be the biggest winners from AI over the next decade.

“Most of the companies anointed as ‘winners’ fairly quickly turned out not to be winners at all…incumbents rarely find a way to adapt their businesses to the new technology that threatens their existence.”

—Alasdair Nairn , Engines That Move Markets

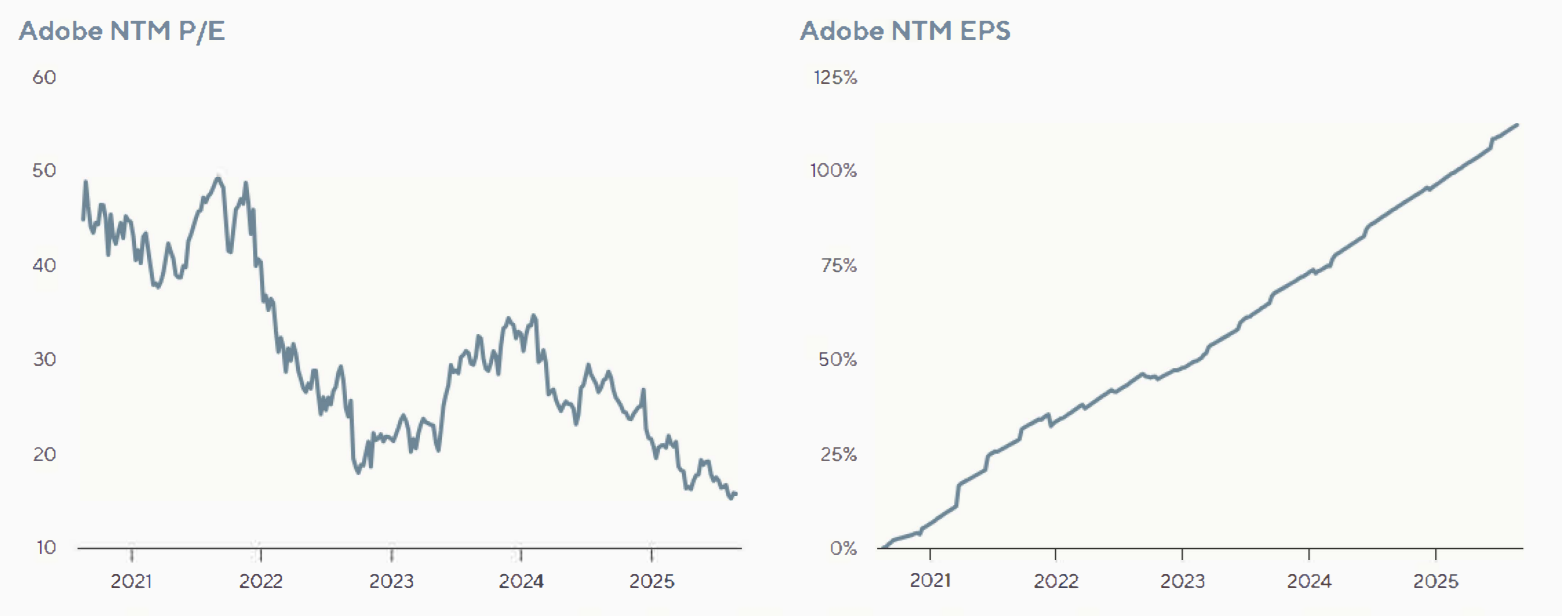

Even in the internet era, the biggest winners only became apparent many years after the bubble burst (e.g. Meta, Google). As a result, we believe investors are not adequately pricing in the risk of disruption. Google’s dominance in search is being challenged by AI advancements like ChatGPT, while software’s once-sticky dynamics are facing erosion, as seen in Adobe’s sharp de-rating from 50x to 15x earnings per share (EPS) despite robust earnings growth. These shifts highlight how quickly market narratives can unravel.

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data from 21 August 2020 to 22 August 2025. NTM: Next Twelve Months. For illustrative purposes only. Content does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it. PAST PERFORMANCE MAY NOT BE INDICATIVE OF FUTURE RESULTS.

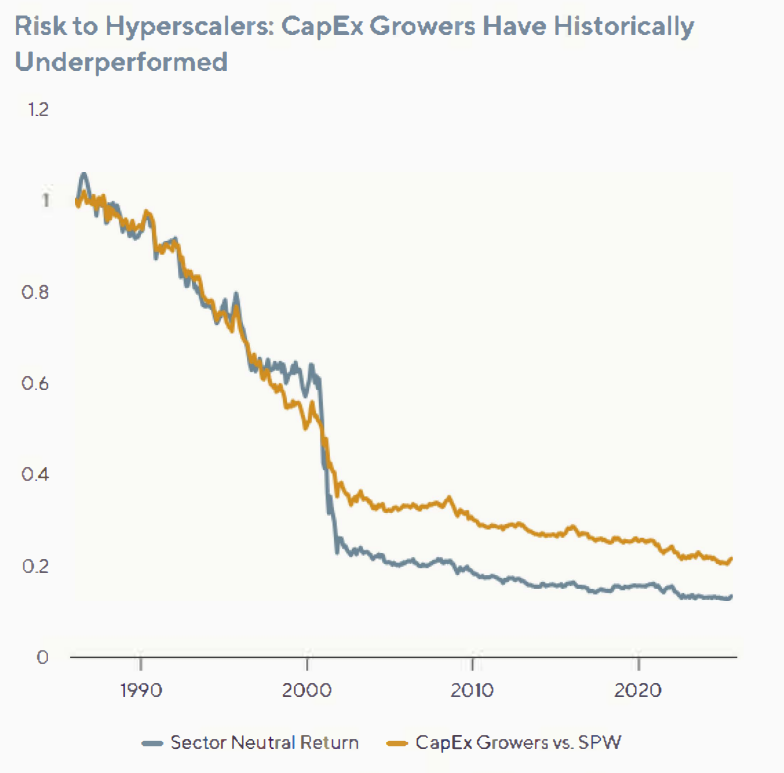

Capital intensity has structurally increased

The third pillar of the big tech thesis during the 2010s was hyper scalability. Unlike most industries, big tech grew rapidly without requiring much incremental investment, allowing them to generate substantial free cash flow. For example, Google raised up to $50 million from inception through its IPO—a figure that would be unimaginable today. Similarly, Meta essentially required no incremental investment for each new subscriber. This argument no longer holds true in the AI era.

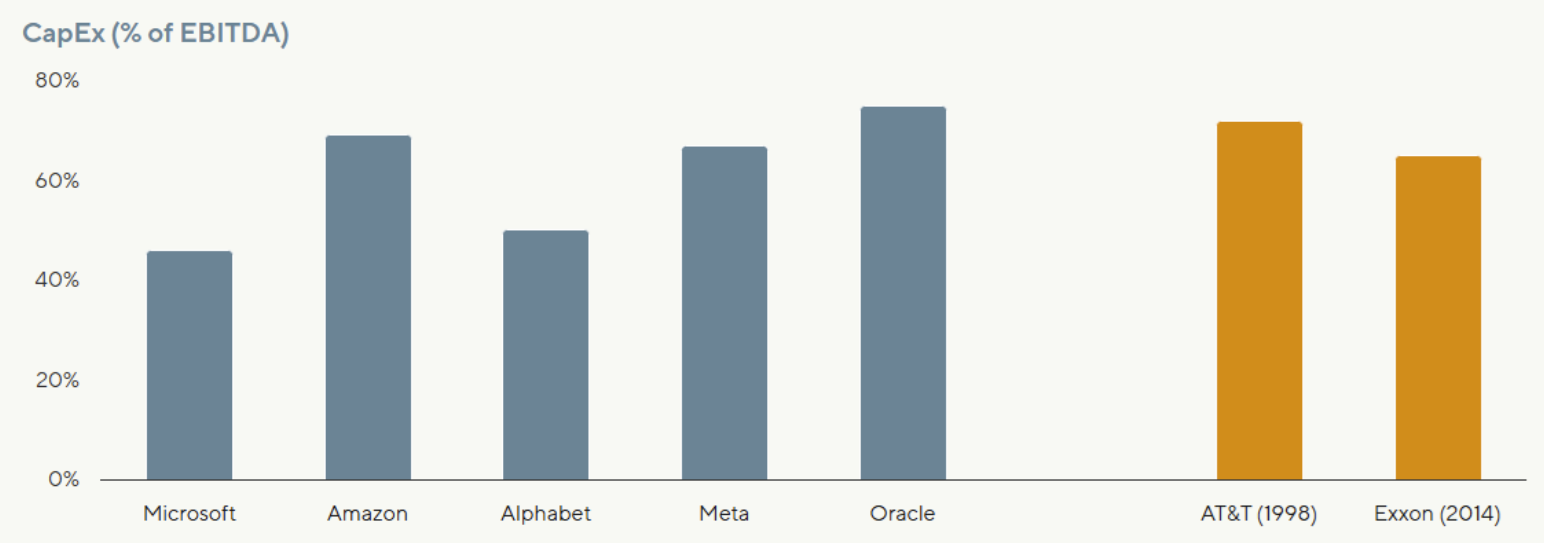

Big tech CapEx as percentage of EBITDA is now running at 50%-70%, which is similar to AT&T’s 72% at the peak of the 2000 telecom bubble and Exxon’s 65% at the peak of the 2014 energy bubble.

Historically, companies experiencing higher capital intensity tend to be structurally poor investments. In other words, AI CapEx has already caught up to prior bubble levels, even after adjusting for big tech’s initial high margins.

In both the telecom and energy bubbles, an exciting new technology (internet for telecom, shale for energy) justified unprecedented levels of investment. Eventually, supply outstripped demand, and the companies never earned a return on their investment, as discussed in our GQG Research Software is the New Shale.15 However, customers benefited massively from cheap internet and energy.

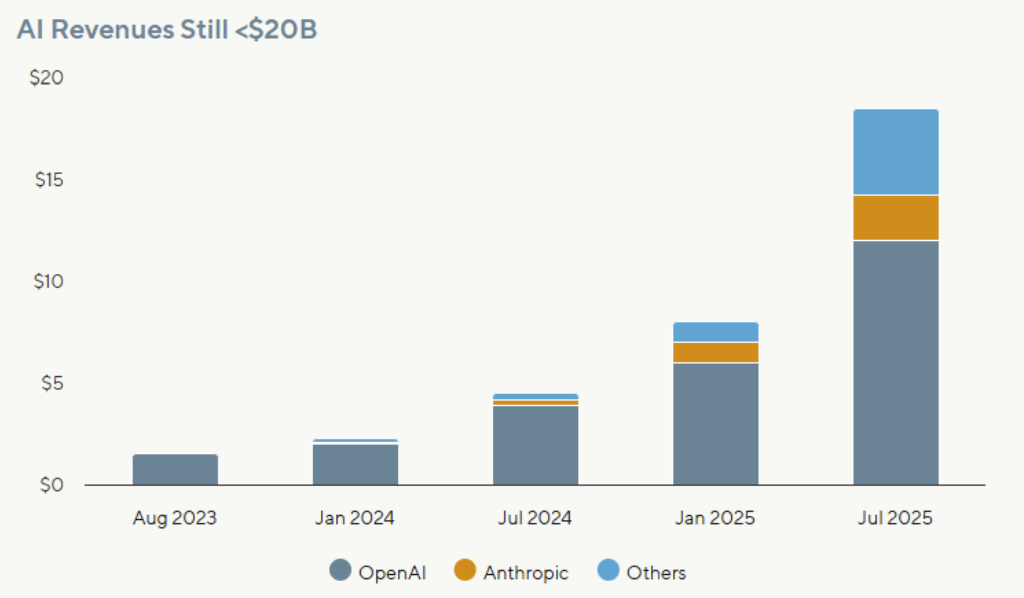

We believe that a similar scenario could unfold with AI over the longer run, but in the short and medium term, the signs are questionable. ChatGPT launched nearly three years ago, yet revenues for the “AI Natives”, estimated to be less than US$20 billion today(16), still pales relative to the approximately US$7 trillion datacenter CapEx expected by 2030. Many potential monetization angles, such as AI smartphones, have ended up being flops thus far.

Cisco 1999 Annual Report

A recent study by the University of Texas found that in 1998 alone, the internet economy in the United States generated more than $300 billion in revenue and was responsible for more than 1.2 million jobs. In just five years since the introduction of the World Wide Web, the internet economy already rivals the size of century-old sectors such as energy, automotive, and telecommunications.

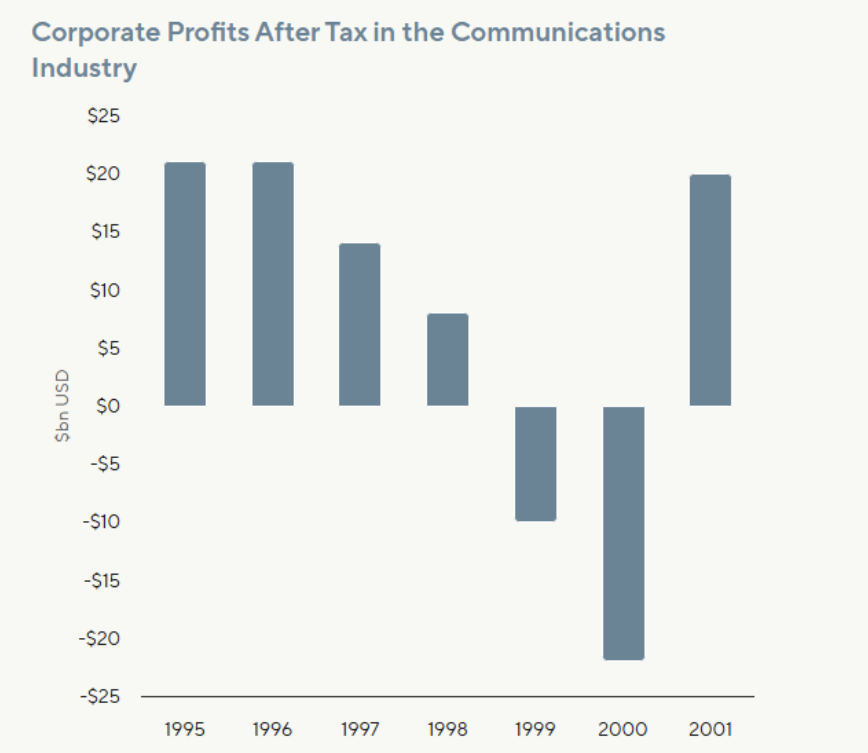

In our view, this is far worse than the internet bubble, which at least generated meaningful revenue. We believe today’s intensive AI CapEx may structurally reduce returns on capital for the entire sector. Indeed, this is exactly what happened to the telecom sector during the 1990s fiber rollout. Contrary to popular perception, telecom used to be a highly profitable sector made up of regional monopolies up until the mid-1990s.

Only three players controlled the long-distance and international telecom market, with AT&T leading the pack at 60% market share. To quote one analyst, “For a long time, the prices and margins for international telecommunications were better than the drug trade…because of competition, those margins are falling and have almost disappeared.”(18) According to a 1999 research report, Vodafone—the largest European telecom company at the time—had an “unmatched portfolio of wireless assets and is positioned for rapid subscriber and EBITDA growth” and that the “scale and geographic scope of Vodafone’s assets are almost impossible to replicate.”19 However, the combination of massive CapEx and increased competition permanently impaired the sector’s economics by the late 1990s.

We think the fatal flaw was adopting a “if you build it, they will come” strategy, where telecom providers assumed new applications would get developed to take advantage of the excess bandwidth. In the end, the killer internet apps eventually popped up years later, but by then, it was already too late for the telecom sector.

We believe that today’s surge of datacenter CapEx and cash-burning AI startups could end similarly to the telecom bloodbath from 25 years ago.

To date, big tech has been able to mitigate the impact of massive CapEx spending on their earnings by repeatedly extending the depreciation periods for their investments. We believe that current depreciation numbers are grossly understated as the hyperscalers need to keep buying the latest Nvidia GPU models, which are released annually, to stay competitive.

In today’s AI arms race, any company that does not buy the latest generation of technology may quickly be at a disadvantage. This is why companies like Oracle are now spending more than 100% of their operating cash flow on CapEx. Once reality sets in, investors may find that earnings are massively inflated due to much higher depreciation.

We may already be starting to see early signs of that. For example, Amazon quietly reduced its useful life for its assets this past quarter due to the “increased pace of technology development, particularly in the area of artificial intelligence and machine learning.”(20)

Misperception #2: Tech companies today are cheaper compared to 2000

We believe simply looking at multiples can be misleading. On a growth-adjusted basis, we found that technology companies today are already more expensive than the companies of the dotcom era. As discussed above, we believe today’s tech prospects are largely deteriorating, and this also does not account for the exuberance on the private side.

For example, an AI startup, Thinking Machines (Founded by the former OpenAI CTO), recently raised US$2 billion at a US$12 billion valuation despite lacking a business model—let alone revenue or profits.21 Similarly, OpenAI is creeping toward a US$500 billion valuation despite only generating US$13 billion revenue while expected to post cash losses in excess of US$8 billion this year.22,23

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data from 1994 to 1999. For illustrative purposes only. Content does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it.

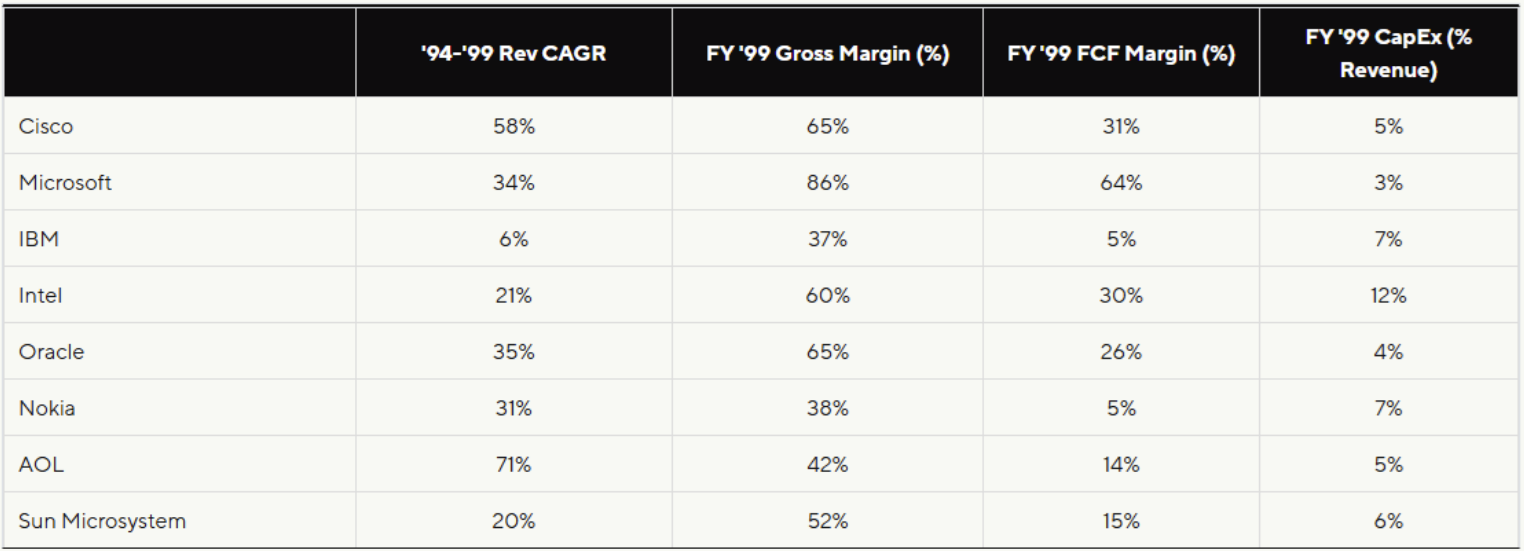

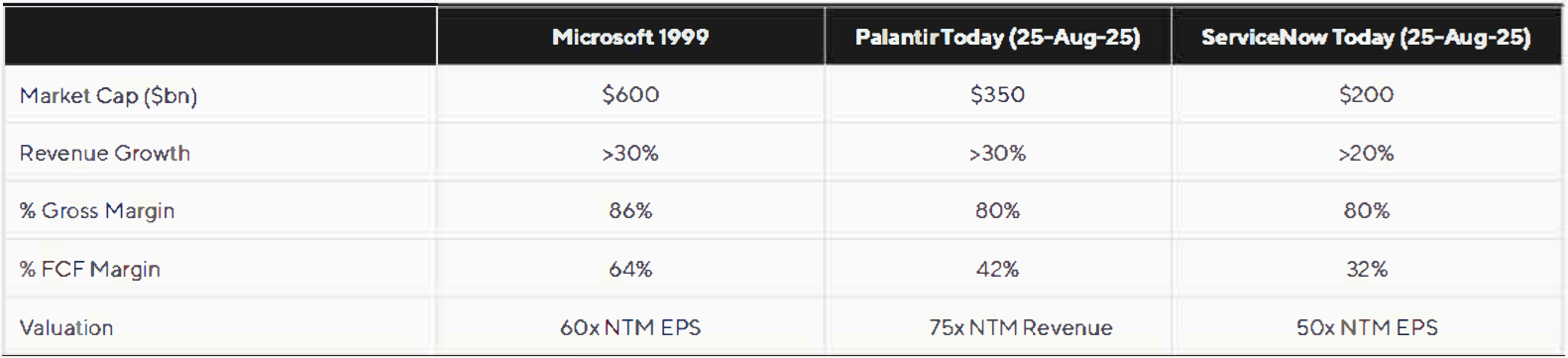

In contrast, big tech in the late 1990s was growing rapidly with minimal competition or CapEx requirements. Like today, there were many low-quality businesses (such as Pets.com), but that was not the case for the mega caps of that era. Microsoft is a great example of the sector’s business quality and growth at the time. In our opinion, this was truly Microsoft at its best: a hyper-profitable monopoly growing rapidly without CapEx and still led by its visionary founder, Bill Gates. At the very peak of the bubble, the company traded at 60x next twelve months’ (NTM) EPS but was growing revenue by about 35% annually, which is significantly faster than almost any tech company today.

Microsoft’s current valuation looks cheaper at 35x NTM EPS, but the company will likely only see low-teens revenue growth,24 while facing increasing competition in its most important segment (Azure) and requiring massive CapEx to grow.

A better analogy would be Palantir or ServiceNow. Palantir delivers similar 30%+ revenue growth but trades at 75x NTM revenue (not EPS). Similarly, ServiceNow trades at 50x EPS, but revenue only grows 20%.

As we now know, Microsoft took 15 years to recover to its 2000 valuation levels, as the stock eventually de-rated to a maximum of 10x EPS despite strong earnings growth. We believe the same could happen to many of the high-flying technology companies today.

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data as of 25 August 2025. NTM: Next Twelve Month. For illustrative purposes only. Content does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it.

We can also look at Cisco, which created the hardware used to power the internet. This was essentially the Nvidia of the internet era, and it briefly became the world’s largest company at just over US$500billion—equivalent to 5% of US GDP at the time–prior to the bubble’s collapse. (Nvidia is currently valued at 15% of GDP.) The core belief then was that internet traffic would double every 100 days, thus requiring massive purchases from Cisco.

According to a research report published within weeks of the peak: “Cisco continues to argue that the industry will grow at 30-50% in countries with healthy economies. It sees several years of strong growth powered by a growing acceptance of the internet as a crucial tool for business and government…Revenues of $4.35 billion rose 53% over the year-prior number of $2.85 billion: FQ2 marked the eighth quarter of accelerating topline growth.”25

In other words, Cisco’s business was booming, hence why it was viewed as a must-own name and traded at more than 20x NTM revenue at the peak—similar to Nvidia today.

Misperception #3: The broader US market today is cheaper than it was in 2000

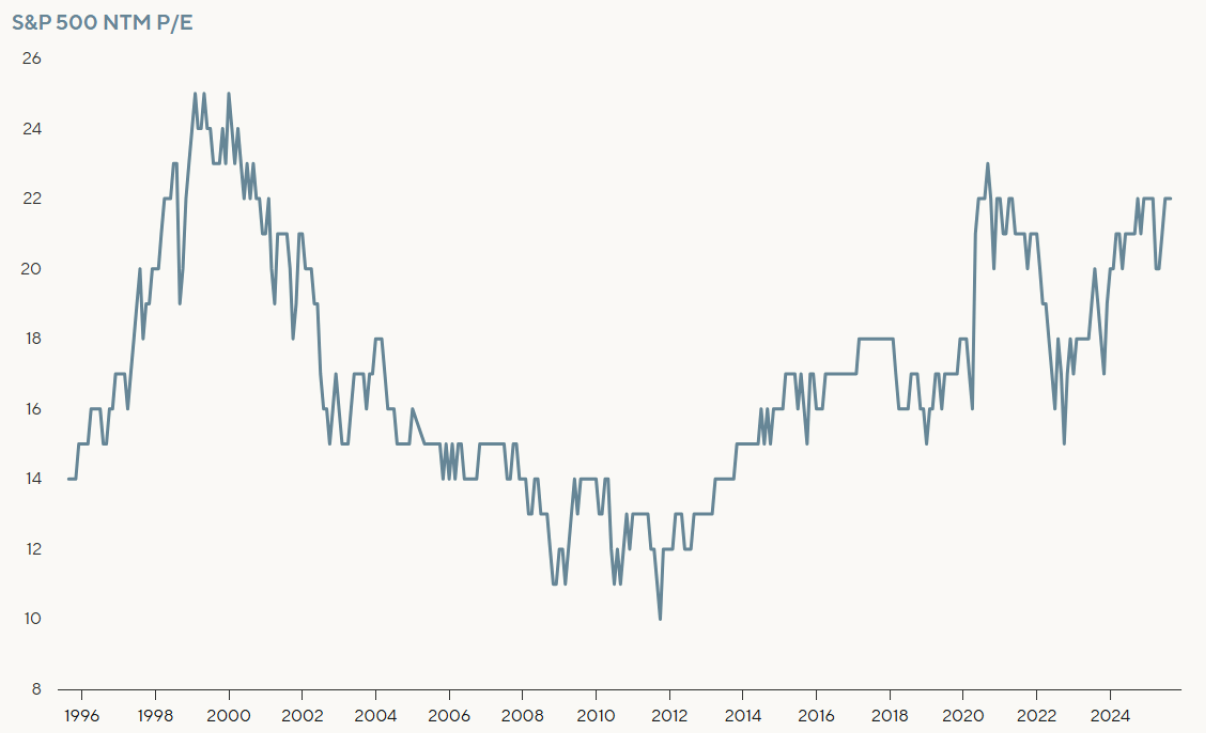

The S&P 500 trades at 23x EPS today, compared to 25x at the dotcom peak in 2000. While interest rates were slightly higher back then, earnings growth was significantly faster and were not artificially inflated by massive CapEx stimulus.

The overvaluation of US equities today appears to echo the dotcom bubble in 2000 and extends into sectors like industrials, financials, retail, and healthcare. In industrials, companies linked to the power theme, such as GE Vernova and Constellation Energy (NASDAQ: CEG), have seen unsustainable multiple expansions, in our view. This feels reminiscent of the 1990s euphoria over internet-driven electricity demand, which ultimately collapsed. Today, the biggest US power generation company, Constellation Energy, is already warning investors that markets are being overly bullish on power demand, although few seem to care at the moment.26

In financials, Robinhood’s meteoric rise to a US$100 billion valuation mirrors Charles Schwab’s ascent during the 1990s, when investor enthusiasm drove stocks to sky-high valuations before years of stagnation. In retail, we think high-quality companies like Walmart (NASDAQ: WMT) and Costco (NASDAQ: COST) now trade at massively inflated multiples, paralleling Walmart’s peak valuation during the dotcom bubble. Similarly, healthcare giants Eli Lilly (NASDAQ: LLY) and Novo Nordisk (NASDAQ: NVO), buoyed by the GLP-1 craze, appear to resemble Pfizer’s 1999 peak, which collapsed in the early 2000s.

Across these sectors, history warns that while innovation drives excitement, valuations can eventually revert—and investors may be in for a rude awakening.

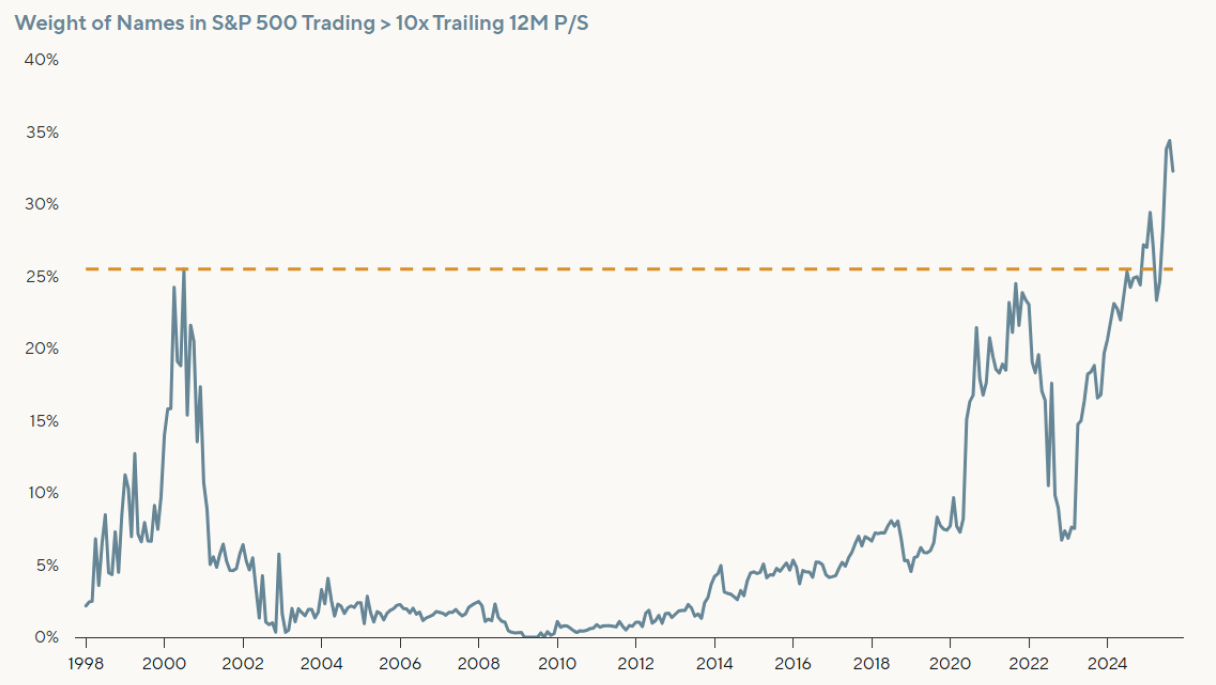

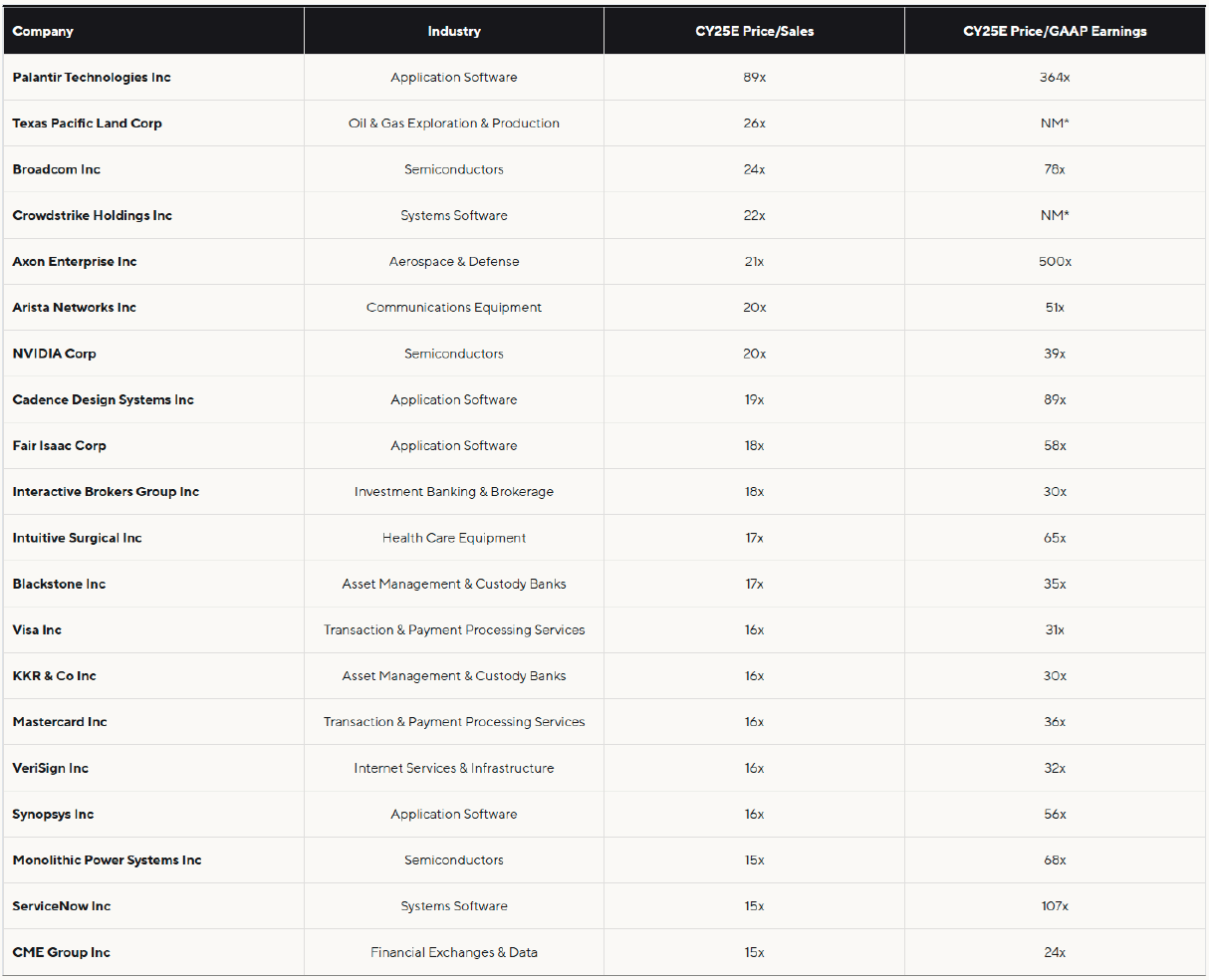

Indeed, these examples only begin to scratch the surface in our view: today’s market features a plethora of companies trading at unsubstantiated valuations, which a simple scanning of the top 20 most expensive businesses in the S&P 500 today (on a calendar year 2025 revenue basis) can quickly evidence. Further to this point, if simply looking at the broader representation of such pricey revenue names in the S&P 500, we’re already well past the Dotcom peak, with 35% of the benchmark’s weight driven by such names, versus only 25% then.

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data as of 8 September 2025. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Source: GQG Partners LLC, Bloomberg. Data as of 8 September 2025. For illustrative purposes only. Actual results may differ from projections illustrated above. Content does not constitute investment advice and no investment decision should be made based on it. *”Not Meaningful” as expected GAAP earnings per share for CY2025 are negative.

Warning signs ahead

At GQG, we rarely turn cautious purely based on rich valuations. However, the trifecta of rich valuations, increasing macro risk, and—perhaps most importantly—deteriorating company fundamentals is very dangerous. We believe much of today’s market leadership has effectively become indexed to the AI theme, whether it be industrials, independent power producers, semiconductors, or capital market businesses.

It is important to underscore just how much more cyclical this broad theme has become—a fact that we believe many quality growth managers similarly underappreciated in 2022, leading to significant losses. Recall that most AI CapEx is funded by advertising revenue, which is extremely cyclical. In the commodity cycle, investors similarly paid a heavy price for confusing inherently cyclical businesses as secular growers.

To be clear, Nvidia was an unquestionably great company in 2018 and 2022, yet the stock still collapsed around 60% in both cases due to the underlying cyclicality. In many ways, Nvidia and other tech giants today have become this generation’s equivalent of the Nifty Fifty ‘one decision stocks’–companies so dominant that they appear untouchable. However, as we noted in an earlier paper, even the best businesses can lead to poor investment outcomes if bought at inflated prices. We would also remind readers that even the best management teams are notoriously bad at predicting inflection points. For example, Jensen Huang, while undoubtedly an exceptional operator, still led investors into significant drawdowns during the recent semiconductor downcycle, like the cheerleading we saw from John Chambers at Cisco, Jack Welch at General Electric, and Jeff Bezos at Amazon in the late 1990s.27

Bulls will surely argue we are in 1995, not 1999—suggesting more upside ahead—but we disagree for two key reasons. First, retail mania. The resurgence of meme stocks, zero-dated options, and levered ETFs mirrors the late-stage froth of 2021, which signaled the end of the last bull run. Second, valuations. Tech names already trade at 1999-like multiples, unlike the reasonable levels of 1995-1998. Giants like Nvidia, at a US$4.5 trillion market cap, leave little room for outsized growth, in our view.

For reference, the S&P 500 traded at a maximum of 15x NTM EPS in 1995 and only crossed 20x near the end in 1998. On a trailing 12-month basis, the S&P technology subset’s price-to-sales ratio is 10x compared to 4x going into 1999, while its price-to-earnings ratio is 42x versus 46x back then. Moreover, earnings growth tells a sobering tale: at the height of the late 1990s boom, broader market growth was on the order of 18% per annum in the five years leading into 1999. Today, that figure sits closer to 10% despite valuations remaining lofty.

This contrast is even more stark when viewed in the context of the fiscal backdrop. In 1999, the US government was running a budget surplus so substantial that senior Treasury officials were concerned about the possibility of eliminating Treasury issuance altogether. As the NY Fed noted in April 2000, the real prospect of paying back all outstanding debt over the next decade sparked concerns about the potential impact on Treasury market liquidity and its role as the risk-free benchmark.28

In our view, big tech no longer offers the unique growth it once did, yet it trades at lofty 30x-50x free cash flow multiples. Meanwhile, we see exciting opportunities elsewhere with the potential for similar low double-digit returns over a full market cycle at what we believe is a significantly lower level of risk. Today, we see better opportunities outside the tech sector.

So, the question for investors becomes: how much of your retirement would you bet on the AI bubble?

19 stocks mentioned

-01%20(1).png)

-01%20(1).png)