High-yield in name only?

During February, global high-yield bonds and US investment-grade debt were trading at record low yields as the bond market’s prolonged bull run continued into 2020.

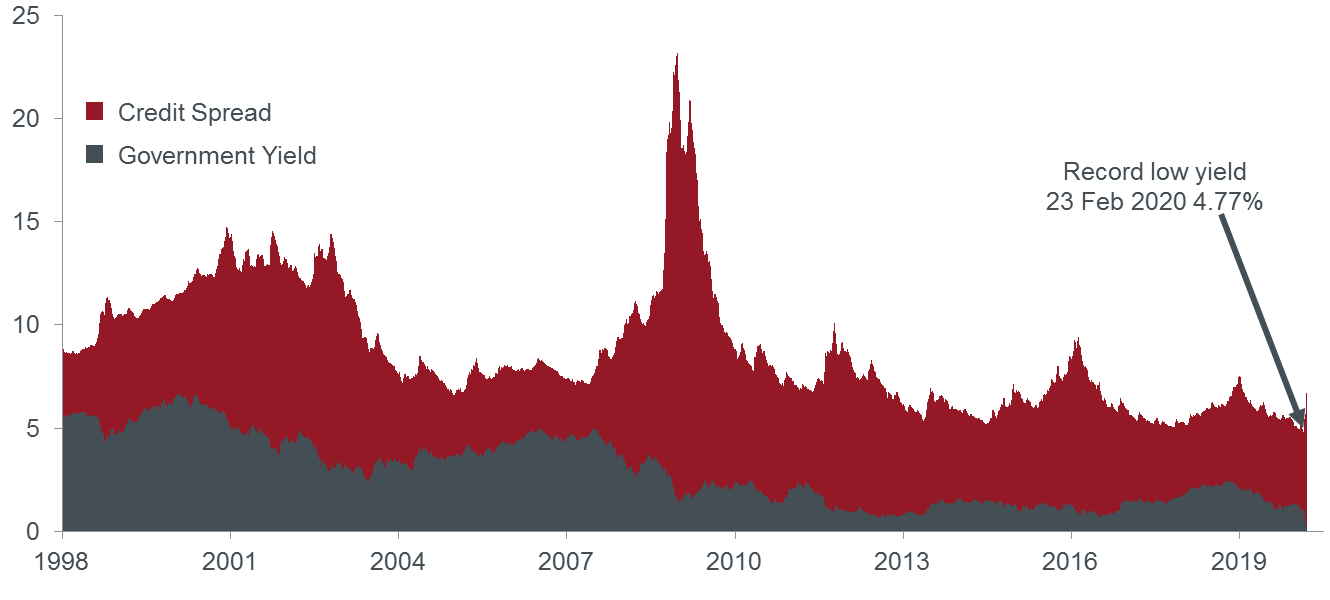

Chart 1: Yield components for the global high yield market since 1998 (%)

Source: ICE BofAML Global High-Yield Index.

The search for yield

Prior to February’s ructions in world financial markets as COVID-19 spread to six continents, investment markets had been characterised by a persistent search for yield amid low interest rates and subdued growth.

Demand conditions appeared strong and issuers of corporate debt sought to capitalise. During the second week of January, we saw US investment-grade corporate issuance record its second highest weekly volume in history1.. Volumes in European high-yield and US and European leveraged loans were also some of the highest ever seen to start a new year.

As a result, we witnessed very low credit spreads – the compensation demanded by investors for bearing credit risk – and very low government bond yields. This is an unusual combination that we have never seen occur concurrently to this degree. This also occurred as equity valuations appeared stretched and new ‘record highs’ were being frequently tested.

This relationship between equity markets and expensive credit markets is normal in strong economic conditions. What was unusual this time around is that very low interest rates also provide little compensation. Central banks continue to hold interest rates at unprecedented low levels and pursue increasingly unconventional policies in a bid to stimulate inflation back into their target range. This interest rate environment is not indicative of strong economic conditions, yet riskier assets appeared oblivious to these signals.

Why do low yields on high-yield debt matter?

Yields on high-yield debt were in their bottom percentile for much of 2020. That means investors weren’t being adequately compensated for the risks implicit in high-yield bonds.

They were receiving less income to protect them from a potential rise in default rates, deterioration in credit fundamentals and potential illiquidity. Furthermore, as noted earlier, interest rates currently provide little further scope to protect capital in a deteriorating risk environment. We now find ourselves with yields on US 10-year Treasury notes setting all-time lows and having breached 0.50%, while Australian 10-year government bond yields recently set a new low of 0.55%

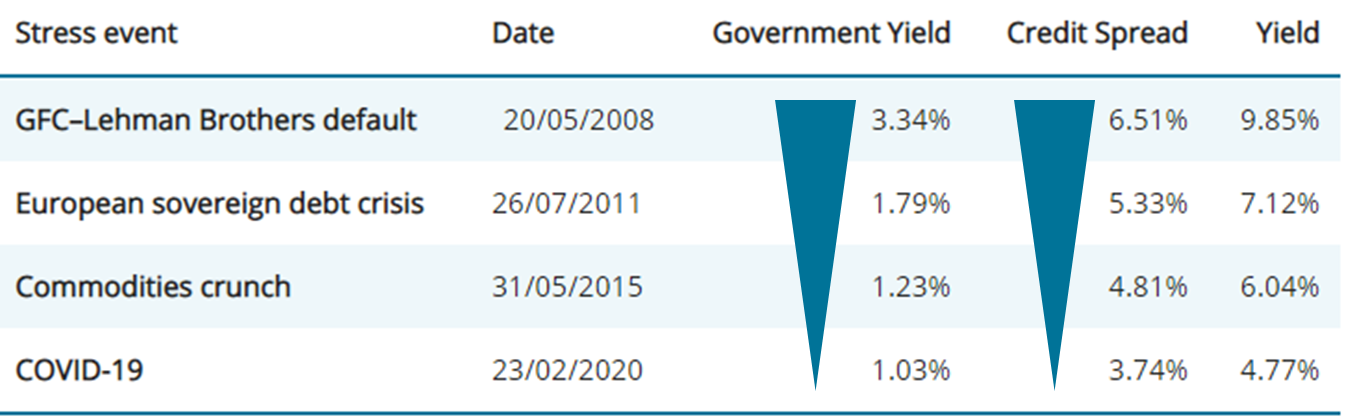

The table below shows that the record low yield from the global high-yield market (before the sell-off in late February) was a combination of very low government yields, and very low credit spreads. The previous three risk-off events occurred from a higher yield level, providing:

- better investor protection via higher expected income, and

- the capacity for government yields to rally and provide some protection from interest rate duration.

Table 1: Global high-yield prior to drawdown

Source:ICE BofAML Global High-Yield Index.

Reflecting on your portfolio

Bonds are generally classified as defensive assets. They are lower risk and subsequently lower return than equities. However, high quality fixed interest acts as ballast and are included in balanced portfolios to outperform when equities and other riskier assets (like high-yield and sub investment grade credit markets) are stressed.

In the pursuit of yield, some investors have increasingly shifted from government and other high quality defensive fixed interest into higher yielding debt, loans and private credit.

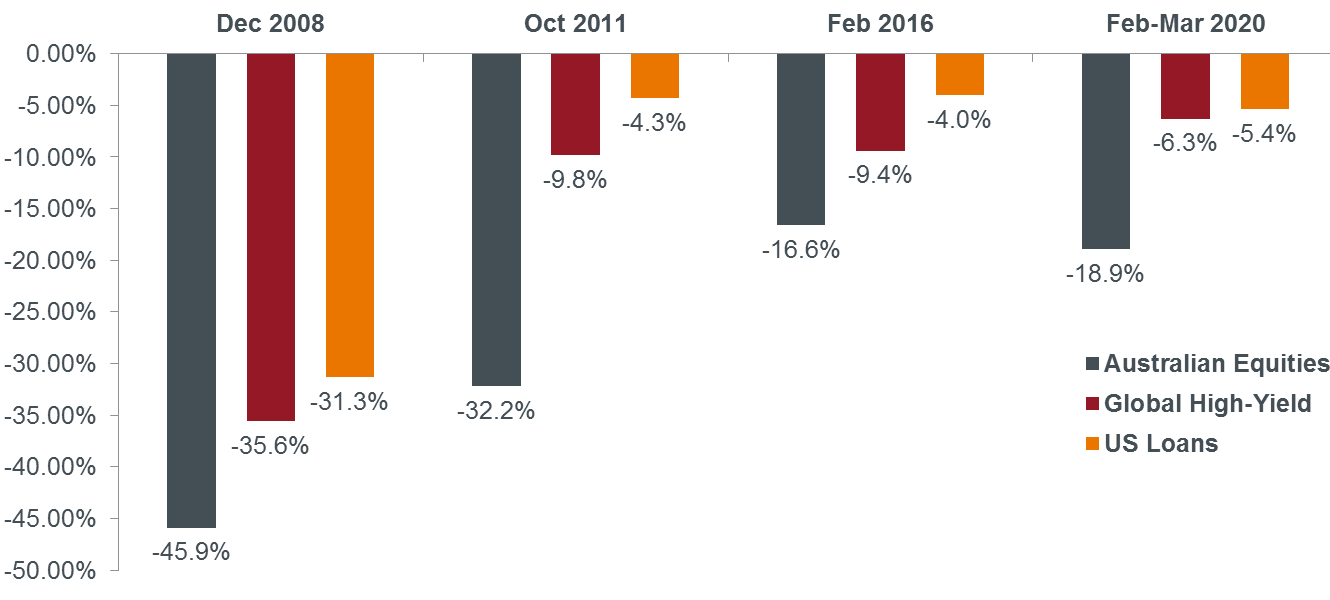

This begs the question: How are you using “high-yielding” debt in your investment portfolio? Is it for principal protection and diversification away from equities? If so, we look back at the key periods of stress in risk markets over the past 15 years. This covers the GFC, the European sovereign debt crisis, the commodities crunch and today’s COVID-19 stress. In a material stress event, the high-yield and leveraged loans, and equities, tend to drawdown simultaneously. During the last two sell-offs the high-yield market lost more than 9%, and lost over 34% during the GFC.

Chart 2: Asset class returns during market drawdowns

Source: S&P ASX200 Accumulation Index, ICE BofAML Global High-Yield Index (AUD Hedged), and S&P/LTSA US Leveraged Loan Index (AUD Hedged). COVID-19 period to 9 March 2020.

The US leveraged loan market has fared a little better, with shallower drawdowns in the post-GFC period, although negative outcomes are still highly correlated to depressed equity markets. A rapid growth in demand from investors desperate for yield has seen the US loan market double in size over the past decade to US$1.2trillion2, and in the process, lender protections have diminished. These include the absence of financial maintenance covenants and weaker credit documentation. “Allowable EBITDA addbacks” dilute leverage-based incurrence covenants, and weaker protections against collateral leakage, all working to the detriment of creditors.

This precondition of weaker protections, tight spreads, and a larger debt mountain leaves the market more prone to a disorderly sell-off in a stressed environment. Weaker covenants also create a high probability that come the next default cycle, recoveries will be materially lower than in the past, resulting in permanent loss of capital.

Unexpected market shocks

With the weight of money chasing yield, stretched equity valuations at a time of modest economic growth, along with record low yields on US investment-grade and high-yield fixed income, the pre-conditions for a market correction were in place.

Often, we don’t know what the catalyst may be. Regardless of the trigger, active risk management is crucial to identify when the risk/reward equation no longer favours investors.

The shock from COVID-19 may be temporary. However, the depths of the shock and ‘peak fear’ remain unknown. In the scenario where the global spread of the virus is slowed and time to develop a vaccine is afforded, markets may be placated by global fiscal and liquidity stimulus. Subsequently the resumption of the weight of money seeking higher income could see yields on high-yield debt resume their downward march.

Conversely, if COVID-19 impacts linger, the more transient dislocations in global supply chains and travel restrictions may transmit into a global demand shock and become a more broad-based challenge to growth.

A closing remark

Holding the appropriate type of bonds can not only act as a defensive asset and allow for diversification away from riskier equities, but also generate income. As such, we feel it is prudent to actively navigate the debt landscape to find the best balance of capital preservation, liquidity, and importantly, risk profile, to ensure an appropriate investment.

With this in mind, the high-yield (if we can still call it that) segment of the bond market can offer investors opportunistic returns from time to time, when receiving appropriate compensation for risk. The current environment of low rates and credit spreads, resulting in record low yields, sees investors accepting all of the risks with very little return benefit.

When liquidity is absent, as we saw in late February, with the US S&P500 suffering its fastest correction in history, only then the true risk borne by high-yielding securities versus lower-risk fixed income becomes apparent.

For more investment insights, visit www.janushenderson.com/australia

1 topic