How should investors navigate stimulus, volatility & shifting fundamentals?

Well, nobody can say that 2025 has been uneventful.

The source of most of the shocks continue to come from the US, with the US Government now in shut down, key economic data releases suspended, and high tariffs firmly in place (and with pharmaceuticals tariffs as high as 200% now being touted). And the US President continues to test the limits of the law, ordering US troops to “straighten out” key Democrat leaning cities.

In my latest macro update, I explore the paradox of booming equity markets amid the political and economic turbulence and also unpack how global monetary and fiscal stimulus—driven in part by US policy shocks—is fuelling asset price inflation, while touching on the effectiveness of traditional monetary economic theory.

I also shares a cautiously optimistic view on Australia’s growth trajectory, highlighting improving financial conditions, the positive impacts of a retreating public sector, and detailing why I still expect three rate cuts from the RBA in 2026.

Recorded 6 October 2025.

Edited transcript

Hello everyone and welcome to our December quarter outlook for 2025, and perhaps a sneak peek at our initial thoughts for 2026.

No one can say that 2025 has been uneventful. The source of most of the shocks continue to come from the US and as we speak the US Government in shut down, key economic data releases have been suspended, high tariffs remain in place with pharmaceuticals tariffs as high as 200% now being touted by the administration. And the US President has ordered US troops to “straighten out” key Democrat leaning cities, continuing the trend of testing the limits of the law.

That sentence alone would in isolation suggest that US equities could have retreated from their recent highs, yet US equities have recovered from a small blip in September to new record highs.

Indeed, the nature of the rally has shifted in recent weeks. Yes, Big Tech is back driving the direction of the market, but unprofitable Growth companies have now joined the fray and resource stocks have attracted renewed interest as Gold prices surge, and expansive fiscal and monetary frameworks across much of the developed world have supported the switch back into resource exposure.

If you are still scratching your head as to why the equity market is higher, the answer is that regardless of what you personally think of Trump’s policies, the reality is that they have induced far greater monetary and fiscal easing outside of the US than otherwise would have been the case.

To put this in context, there have been 168 interest rate cuts by global central banks so far this easing cycle, compared to the 196 cuts during the emergency recession response during the pandemic. Not only is this the third largest number of global interest rate reductions in a cycle since the early 1990s recession, it is pretty clear that the current easing cycle is not complete.

Similarly, the unsettling of the world security order has driven an extraordinary lift in military spending commitments around the globe, including at home, adding to the broader tone of policy stimulus.

It seems a rather cynical and almost depressing reason to buy equities, but perhaps the simple addition of all this stimulus is all that really matters, the rest is currently being treated as noise.

What about U.S. fundamentals?

There is an element of the rally in recent weeks that can be attributed to better economic growth and slightly lower than expected inflation in the US.

However, the source of the recent growth surprise has been stronger consumption growth, despite low saving and a sequential slowing in core income growth. Indeed real household income is no longer expanding and spending is increasingly skewed to high income earners, so whether growth can remain so strong is an entirely different question. I expect that activity growth to slow pretty sharply again in Q4, as the labor market remains very weak. Further tariff driven price rises will weigh on real incomes further, and I think we will see further pausing of investment projects due to tariff-related uncertainty and that should start to feed through to the broader economy. That will maintain the pressure on the Fed to ease policy further, but the question is will risk assets reward monetary easing that is occurring because economic growth is slowing, the labour market is fragile and inflation is still uncomfortably high?

If US equity markets don’t falter it may simply be a case of US households allocating to equities as the return from their deposit accounts decline. One of the under-appreciated facts about US households is that liquid assets are now close to equal to total household liabilities. This is vastly different to 20 years ago when liabilities greatly exceeded assets.

Similar to Australia, monetary policy loses its power through the “cash flow effect” when interest bearing deposits are equivalent to the levels of debt, and this may have some perverse influences. For instance, if an economy has slowed sufficiently to justify monetary easing designed to boost nearer term spending, but the starting level of interest-bearing deposits is unusually high, then lower Fed interest rates could merely push more funds into equities at a time of already inflated valuations. Given general nervousness over government debt levels and bond allocations and historically narrow credit spreads, then this may help explain why we are seeing a late cycle melt-up in equities and alternative investments such as crypto.

If you step back and think about how this changes the transmission of monetary policy, then policy becomes far more dependent on the wealth effect rather than the cashflow effect. The theory behind much of economic thought is that lower interest rates induce households to consume more today and save less for the future. However, if lower interest rates merely see already cashed up households swap their interest-bearing deposits into riskier assets, and in the process bid up asset prices, then the basis of much of our understanding of monetary economic theory comes under question. Lower rates may not engender much of boost to household spending, given there is no cashflow benefit on net, until such time that asset prices rise sufficiently to drive spending.

If a monetary easing cycle becomes more dependent on driving up wealth to forestall slower activity growth, then this also has significant distributional impacts on households. We are entering a new era here. One where the lags between monetary policy and the impact on the real economy becomes more uncertain and one where central banks twin objectives of inflation and full employment now look like a three-legged stool where they increasingly have to incorporate the pace of wealth creation (or destruction) into their deliberations.

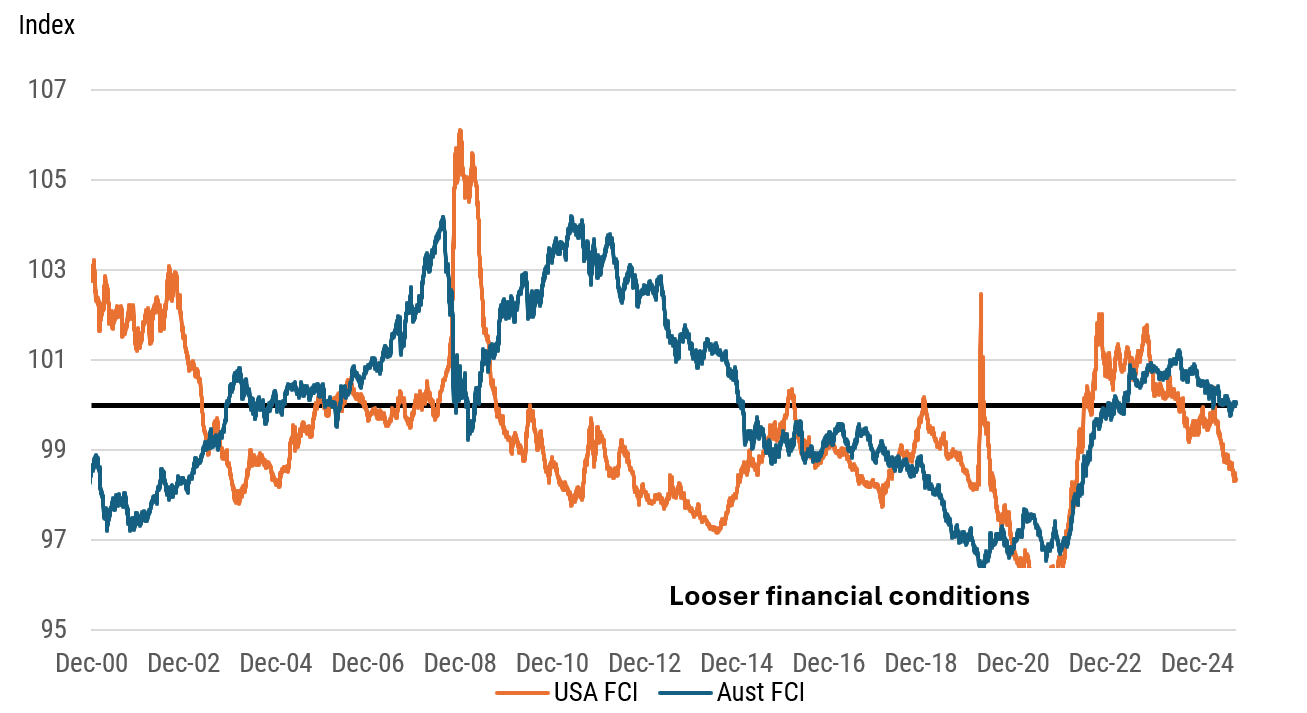

I have long been an advocate of financial conditions, partly because it partly addresses some of these issues as it incorporates the interaction central bank interest rates, asset prices and FX.

Australian and US financial conditions indices

Source: YarraCM

A glance at our chart of US and Australian financial conditions reveals that financial markets have clearly been doing the easing work for the Fed. Indeed, one would question why the Fed would consider easing policy at all, let alone the four additional cuts currently priced by Fed fund futures. The answer to that is, obviously, concerns over the spluttering labour market.

Currently, the hiring rate has plummeted in the US and increasingly the same is true in Australia. However, thus far the firing rate has remained relatively low. One suspects that the Fed is watching layoffs like a hawk at present. From our perspective, the US will again breach the Sahm rule and recession discussions may well be rekindled into calendar year end, assuming of course that the BLS publishes the data in a timely manner. In any case, there is a greater risk that the Fed disappoints the Doves in the nearer term, given just how loose financial conditions have become recently, and as such the risk a modest drawdown in risk markets remains in Q4.

The Australian Outlook

Switching to the Australian outlook, encouragingly, much of our central view has been playing out. The consumer has engaged with strong free cashflow growth underpinning their spending recovery, housing construction looks set to provide some meaningful contributions to growth over the year ahead, the outlook for private investment growth remains for modest support while the public sector is finally starting to retreat from being the primary source of economic growth.

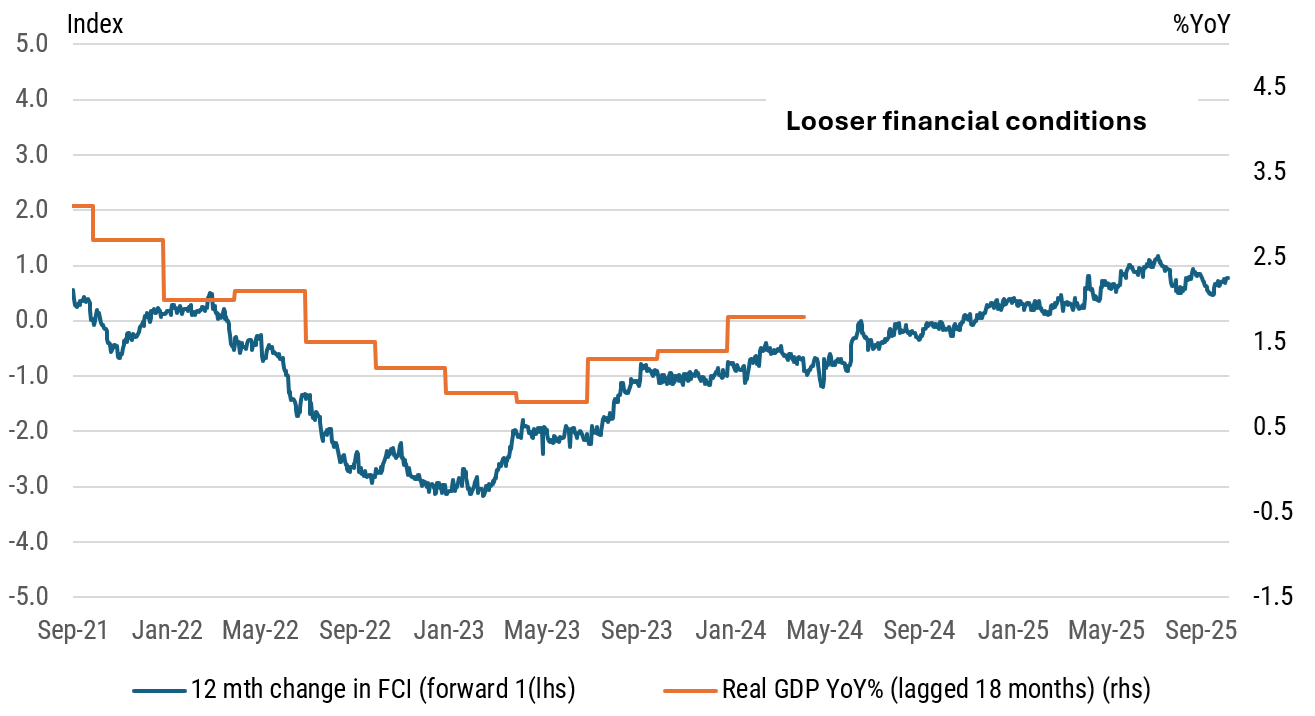

This is a much more constructive mix of factors to support economic growth over the next 12-18 months. Note that financial conditions in Australia have also eased but have only eased to be around what we think is a neutral setting – consistent with trend economic growth within the next 12-18 months.

So, we are still expecting a steady cadence in terms of the pace of the economic recovery, but there is some scope for the economy to surprise on the upside into mid-2026.

Australian financial conditions index

Source: YarraCM

The accumulation of evidence that the economic recovery is on track and financial conditions have continued to ease, without RBA assistance, have met with signs that the September quarter CPI in Australia may print higher than the RBA forecast in August. The combination was sufficient for us to jettison our expectation for a November rate cut, with our next forecast rate cut not expected until May 2026. This doesn’t mean that a November rate cut is impossible, however, the onus is now clearly on the inflation, employment and activity data to surprise materially on the downside in coming weeks and that seems less likely given the information at hand.

With respect to the monthly CPI data, the RBA has been at pains over recent years to say it was too volatile to trust, but now have taken some signal from the shift in its easing bias to effectively a near-term neutral stance given the surprises we’ve seen over the last two months. Much of the upward surprise in the monthly CPI was merely base effects and eliminations of household utility subsidies. It is possible that the quarterly numbers are more benign, but for now it is convenient for the RBA to pause and assess whether policy is actually having its desired effect.

It is also worth noting that the RBA held its annual internal conference recently and although the full details are not made public, it was very clear from the external speakers and the papers presented at the conference that the RBA is entertaining the idea of a fiscal r*.

This is the idea that there is a fiscal setting that is consistent with neutral interest rates. By way of background, r* is a rate of interest rates that is consistent with the economy growing at trend, and inflation being at the midpoint of the target band. The idea is that this fiscal r* works in conjunction with the monetary r*, whereby forces such as population growth, productivity and the levels of savings determine where neutral interest rate settings are.

I raise this because last quarter I made the suggestion the RBA looked set to lower their estimate of r*. Despite a lot of conjecture in the press, it was very clear during the quarter that the RBA Governor did exactly that, lowering the estimate of the r* by 50bps we believe from the last time the RBA referred to a estimate in Nov 2024. So we might have been correct in that regard, but what we didn’t envision is that the RBA and other central banks now appear nervous that fiscal policy may be less self-correcting and as such the fiscal r* may be higher. In effect, governments are working against a sustainable lowering of the neutral rate. Whether this is a direct warning to the Australian government remains unclear, but I doubt Treasury missed the hint.

So the question is does this mark the end of the easing cycle? I still think the answer is no. Australian fiscal finances are materially better than their peer group and are likely to continue to get some help from the resources sector over the remainder of the year. So fiscal r* issues should be less pressing an issue for us compared to our peer group.

More importantly, as the public sector retreats as a driver of economic growth in coming quarters, Australia will see a marked rise in measured productivity growth and a decline in real unit labour costs. These feed directly into the RBA’s inflation forecasting models and, combined with what I see as still a pretty friendly inflation outlook, there should be no barrier to the RBA re-engaging in a slow-motion easing cycle from May 2026. For that reason, I still have three rate cuts embedded in our forecasts for 2026 and that should continue to keep the pace of Australia’s economic growth recovery ticking over and remain a broadly supportive environment for active investors.

Last quarter we said that equity markets would remain bumpy in Q3 but our bias was to add to local over global positions, and the steeper trade in rates markets would likely pause in Q3 as nearer term US growth concerns began to dominate longer term debt sustainability concerns. And we also thought the A$ had room to grind higher. On balance that is what played out and we were happy that after advocating that Small and Micros in Australia should outperform, that they were certainly the place to be in Q3 and now YTD. In many ways we see a continuation of these dynamics in the December quarter.

So perhaps some nearer term market turbulence, but a supportive local and emerging market growth environment should continue to support A$ denominated assets in the period ahead.

That is probably a good place to end things. Best of luck for the quarter ahead.

Read our perspectives on markets, trends and opportunities

Yarra Capital Management is powered by senior professionals who are part-owners of the business. We value research, insight and analysis that helps us identify the best opportunities for superior and sustainable returns over the longer term.