Identifying rising stars

At Montgomery, we focus our efforts on identifying high quality companies with bright prospects. When combined with a disciplined and patient approach on buying at a discount to fair value, we believe that in the long term, these companies provide an attractive combination of stronger returns with lower than average risk.

In assessing the prospects of companies, we look at the potential for growth in its industry. There are many macroeconomic factors that provide a good starting point in identifying companies that potentially have bright prospects.

One example is the impact of long term demographic changes. For example, most developed economies are grappling with aging populations as a result of the combination of increased longevity and the disproportionally large baby boomer population moving into the retirement phase. This is a trend that will continue to affect industries on a long term basis and throughout future economic cycles.

This sets a framework within which to identify beneficiaries of this long term trend, but having identified some broader trends and drivers, we need to identify the beneficiaries.

As people age, their healthcare requirements increase. As such, healthcare companies will benefit from stronger demand growth. There can also be opportunities in companies that support the core healthcare industries such as insurance.

In financial services, the needs of retirees are different to those that are at an earlier stage of their working life. Retirees are more focused on income rather than wealth accumulation. As such, there is a likely to be a shift in demand away from traditional superannuation and mortgage products in favour of interest and other income generating assets like annuities.

Demand for providers of leisure time activities that suit an older demographic are also likely to benefit from a combination of strong growth in the number of older people and an increase in their available leisure time in retirement.

The broader macro environment provides the potential for superior revenue growth, and identifying the company that is best positioned to benefit and deliver the most attractive investment characteristics is a function of quality.

The quality of a business is impacted by a number factors. An important measure of quality is the ability to generate a high return on the capital the company has invested in its businesses. This can be measured in a number of ways such as including or excluding the impact of balance sheet gearing through debt financing, or in looking at the return generated on tangible or total capital employed in the company. Different measures of returns provide slightly different pieces of information.

The very best companies can retain a high proportion of their profits and reinvest them at high rates of return. The compounding effect of this sort of reinvestment on earnings growth is extremely powerful in driving increases in shareholder value. However, the key component of this equation is the return the company generates on the incremental capital it invests. For example, assume a company retains and reinvests 50% of its earnings back into its business. If the company generates a 10% return on the incremental capital reinvested, its earnings would increase by 5 per cent. If instead it reinvested its capital at a 20% return, earnings growth would be 10 per cent.

This seems like a fairly simple thing to look for; just find companies that have generated a high rate of return and have a low dividend pay out ratio. However, it’s not the historic or average rate of return that is important. Rather it is the return generated on the incremental capital invested. This can be significantly different to the average return on capital generated by the company in the past.

First, historical returns based on the reported earnings and balance sheets can be distorted by accounting policies and decisions. A classic example is large asset write downs that are taken as ‘significant items’. These reduce the book value of the capital invested by the company as set out in the balance sheet statement. This reduces the denominator in the return equation, artificially boosting the return on capital in future periods. The write down does not improve the company’s rate of return on incremental capital reinvestment, but it can materially impact the historical return calculation.

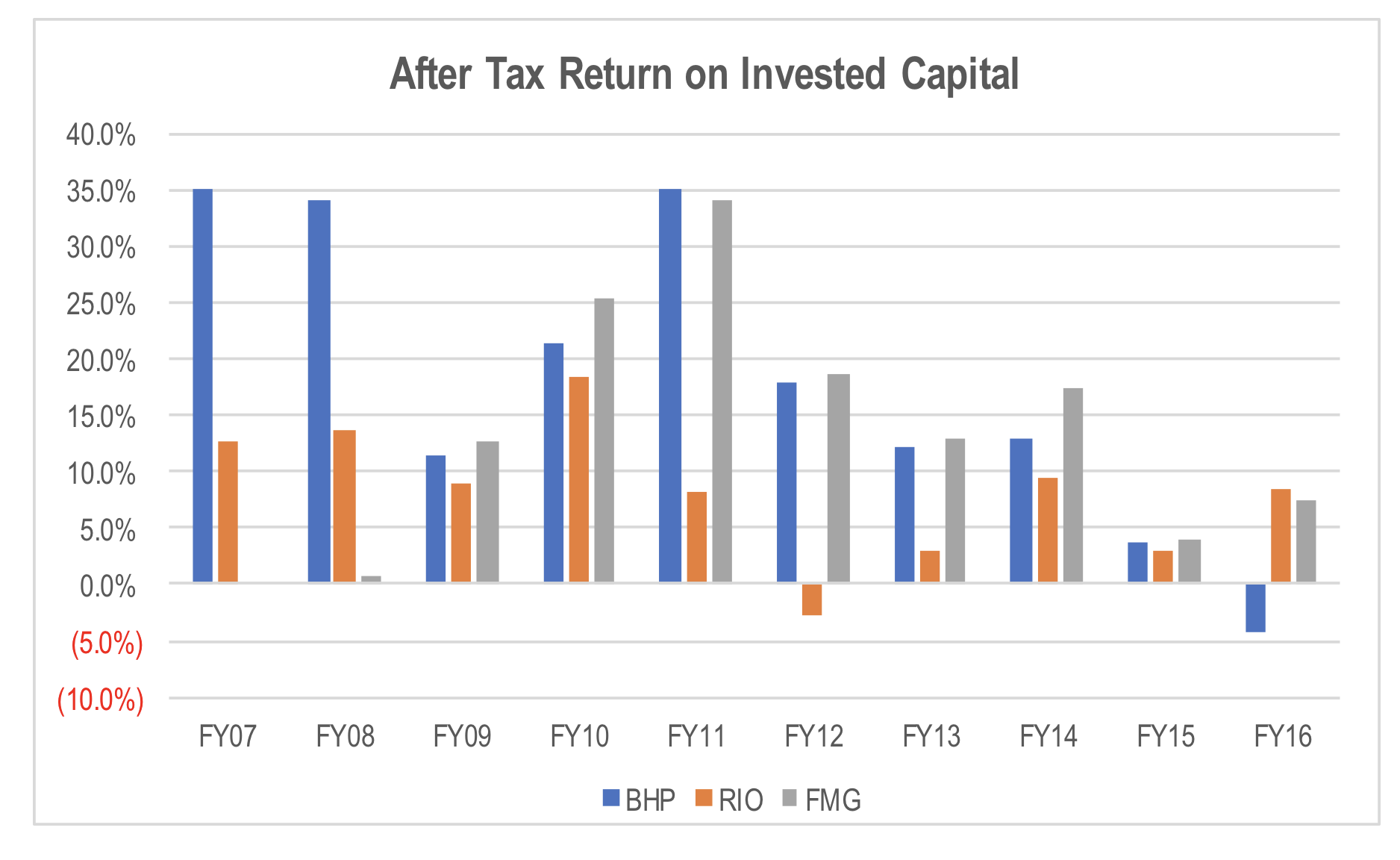

The other problem with historical returns is that they are based on historical industry conditions. An extreme example of dangers of assuming historical returns are a good proxy for future incremental rates of return on capital are the mining and mining services industries. If we looked at the average return on capital employed by the big iron ore miners in Australia over the last 10 years, it would indicate average returns in the mid to high teens on an after tax basis.

However, historical earnings and returns were buoyed by extremely high iron ore and other commodity prices in the previous decade, which resulted from China’s strong economic growth and the lags in bringing new mining production capacity online. Since then, global production capacity has ramped up due to heavy reinvestment by mining companies, and at the same time, China’s rate of economic expansion has slowed. Consequently, the peak commodity prices that delivered the miners high returns historically are unlikely to be repeated in the foreseeable future. As a result, the return that the miners can be expected to generate on future capital reinvested in their businesses would be lower than their historical rates of return.

One of the hallmarks of a high quality company is that it is able adjust its business model to mitigate the impact of any external influences.

Understanding the overall industry value chain and the competitive position of those within that value chain of the industry is vitally important in assessing the robustness of a company’s margins and return on capital employed in the face of changing market conditions. Understanding the competitor set and substitutes can identify risks to the investment case.

For example, a vertically integrated competitor that covers more than one segment of the value chain can signal a risk to the returns generated by a company that operates in just one part of the value chain. This is because it can redistribute pricing, margins and returns from the segment with more competitors to another segment with less competition. As example would be a company like Telstra raising wholesale network charges while maintaining retail prices. Resellers of Telstra’s network would then incur higher access costs but receive no relief from margin pressure through higher retail prices in the market. The result is lower margins in the retail segment but higher margins in wholesaling.

In understanding the company’s position in the value chain, its competitive advantages relative to other players in the market, and supplier and customer power, an investor gains insights into the pricing power of the company and barriers to entry to its market.

Pricing power reduces the risk that an external shock or change to the market causes a structural change in the company’s margins and return on capital. Barriers to entry protect the business from increased competition that can dilute margins and return on capital. Consequently, these key attributes of a high quality business reduce the investment risk.

The final element in identifying a good investment and minimising downside risk is buying the stock at an appropriate price. This requires the investor to determine an appropriate value for the company. The incorporation of an appropriate margin of safety is important to ensure downside risk is limited, and this will depend on the risk characteristics of the company.

Once all of these factors have been assessed, the final and often most difficult factors are patience and discipline.

To read more articles written by me, click here.