Is cash still king?

While the wild swings in share, credit, currency, and commodity markets have garnered most of the attention in the months following the COVID-19 outbreak, cash markets in Australia have seen some highly unusual movements that demand further scrutiny.

Will the real cash rate please stand up?

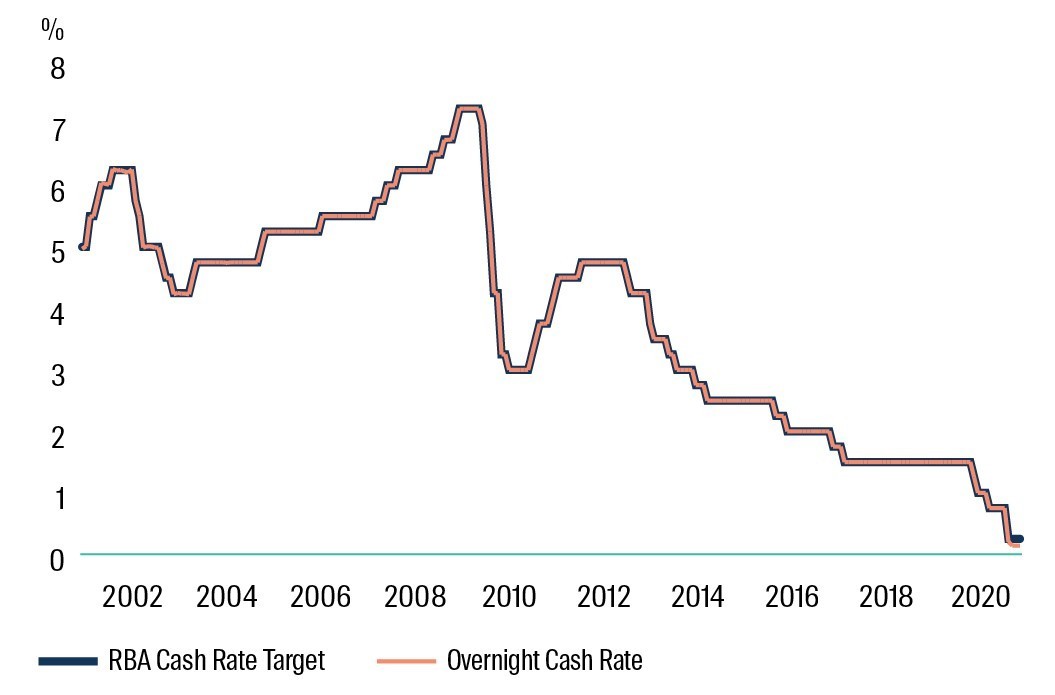

Most people are aware that the cash rate target set by the Reserve Bank of Australia (‘RBA’) is at a record low of 0.25%. However, many do not know that the actual overnight cash rate – determined in the overnight lending market – is currently lower than the target. Whilst not completely unprecedented, there have only been rare times and sporadic days where a difference has materialised over the past two decades.

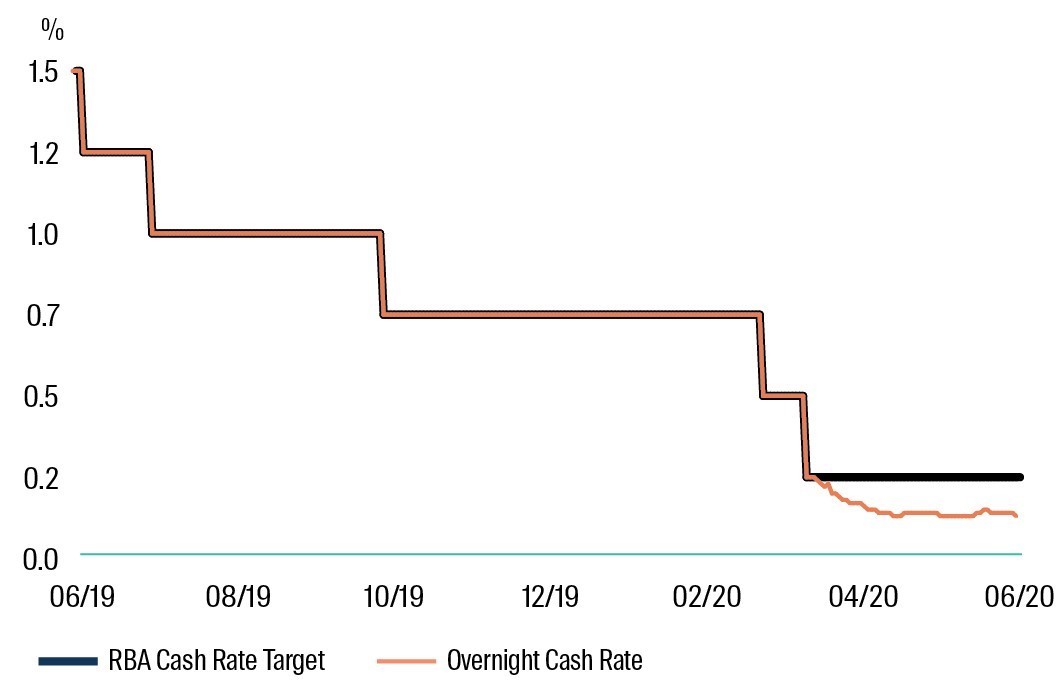

One year ago in early June 2019, the cash rate target in Australia was at 1.50% although this has subsequently been reduced by the RBA five times in 0.25% increments to the current all-time low level of 0.25%. March 2020 saw two cash rate reductions – one during the Reserve Bank’s normal monthly meeting on 3 March and another off-cycle cut on 19 March which also saw a range of other announcements made by the RBA including an aggressive asset purchase program (also known as quantitative easing). While the RBA has been on hold with respect to the cash rate target since these announcements, we have seen the actual overnight cash rate steadily fall from the target to around 0.13% today (see charts – data as at 15 June 2020).

Australian Cash Rate – Prior 20 years

Australian Cash Rate – Prior 12 months

Source: Bloomberg as at 15 June 2020

There are several reasons why this divergence has occurred.

- First, the major banks in Australia are earning a bit more than usual on their overnight accounts with the RBA. These accounts are known as ‘exchange settlement accounts’ which are used by banks to settle transactions amongst themselves and with the Reserve Bank each day. After markets close every day, each bank agrees with the RBA an amount required to buffer their intraday payment needs. Any exchange settlement balance above the required balance is classified as ‘surplus’. The rate paid on surplus exchange settlement account balances is usually 0.25% below the cash rate target while the rate the RBA lends to banks overnight is typically 0.25% above the cash rate target. However, once the cash rate target moved to 0.25%, instead of paying banks 0.00% on their surplus balances, the Reserve Bank decided to pay 0.10%. This small positive return has made it more attractive for banks to park money overnight with the RBA.

- Second, there is an enormous amount of ‘excess’ liquidity in the banking system due to increased RBA actions – namely the direct buying of bonds and increased short-term lending to financial institutions through repurchase agreements or ‘repo’. The bond purchase program has been designed to push the yield on 3-year Australian Government Bonds down to 0.25%, which has largely been successful. Repo operations basically allow eligible collateral to be pledged to the RBA in exchange for short-term funding – what counts as eligible has been massively expanded in recent months to help banks and non-bank lenders in particular who can now pledge an expanded spectrum of credit securities along with the usual Australian Government and State Government paper.

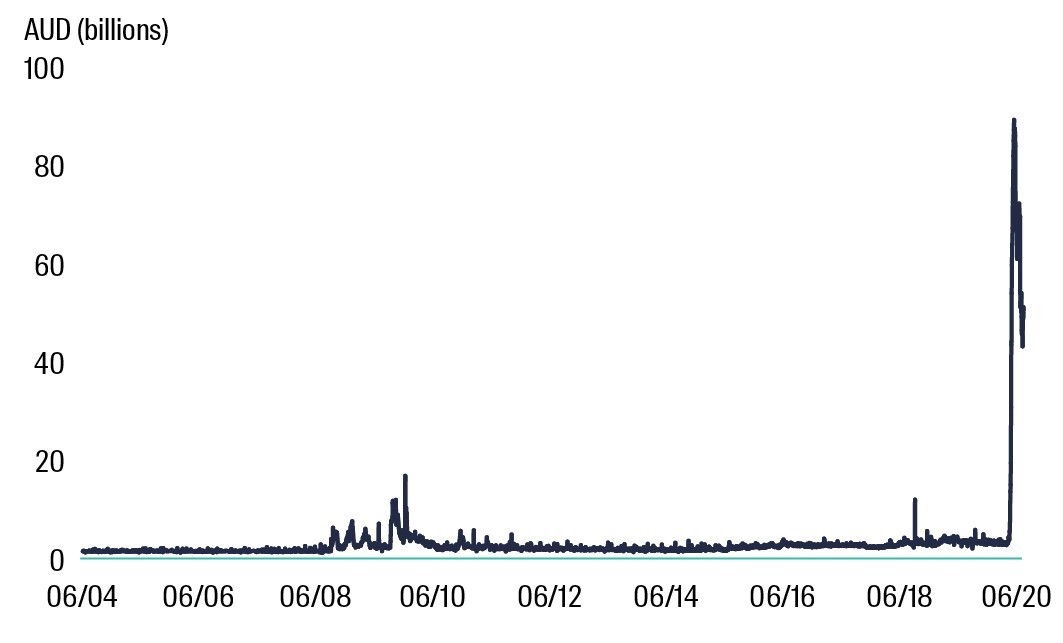

- Finally, banks have wanted to surround themselves with liquidity during an understandably uncertain time and do not want to be in a position where they are anywhere near falling short of having enough liquidity to settle transactions such as large withdrawals of deposits. Therefore, there has been a huge spike in banks’ appetite to use their exchange settlement accounts since the crisis unfolded in early March, leading to large surplus balances. Although these surplus exchange settlement balances have fallen from their peaks several months ago, they remain elevated (see below).

Taken together, the banking system does not need to borrow reserves overnight and nearly all would like to lend reserves overnight. The old adage of ‘more buyers than sellers’ is the ultimate reason why the actual overnight cash rate remains around 10 basis points below the target rate of 0.25%.

Cash appears to remain king, at least for the banks.

RBA Surplus Exchange Settlement Account Balances

Source: Bloomberg as at 15 June 2020

Bank Bill(ions)

While the cash rate dynamics are highly unusual, perhaps even more puzzling is that money market securities which typically offer margins above the cash rate have been trading well below both the target cash rate and actual overnight cash rate. While this phenomenon is often a precursor to cuts to the cash rate, the RBA has been persistent and clear – it is very unlikely that rates will be cut further from here and that 0.25% is their ‘effective lower bound.’ So what is going on?

Banks in Australia borrow money from a variety of sources. Individual mums and dads with savings accounts are effectively lending a bank money in exchange for interest on these deposits. Along with using deposits, banks fund their operations and additional lending activity by borrowing in the capital markets – both in Australia and offshore. They seek to diversify these sources by issuing bonds in various currencies, maturities, and across different points in the capital structure (e.g. secured, senior, subordinated, etc) to appeal to a range of investors.

Banks typically borrow for shorter periods (< 6 months) by issuing discount securities called Negotiable Certificates of Deposit (‘NCDs’) which can be traded in the secondary market. Banks can issue billions of dollars worth of NCDs per day. Historically, this market was dominated by instruments called Bank Accepted Bills of Exchange (aka ‘Bank Bills’). Over time these became less favourable to issue by the banks and more cumbersome to trade by market participants so gradually Bank Bill issuance has reduced to near zero in favour of NCDs. Although NCDs are structured differently and are covered under different financial legislation, they trade more-or-less homogenously with Bank Bills and therefore the convention in the market is to use the terms interchangeably. The Bank Bill Swap Rate (‘BBSW’) and Bloomberg AusBond Bank Bill Index are essentially determined through trading on these securities. When someone refers to the ‘Bank Bill’ market in Australia, they are really talking about major bank NCDs.

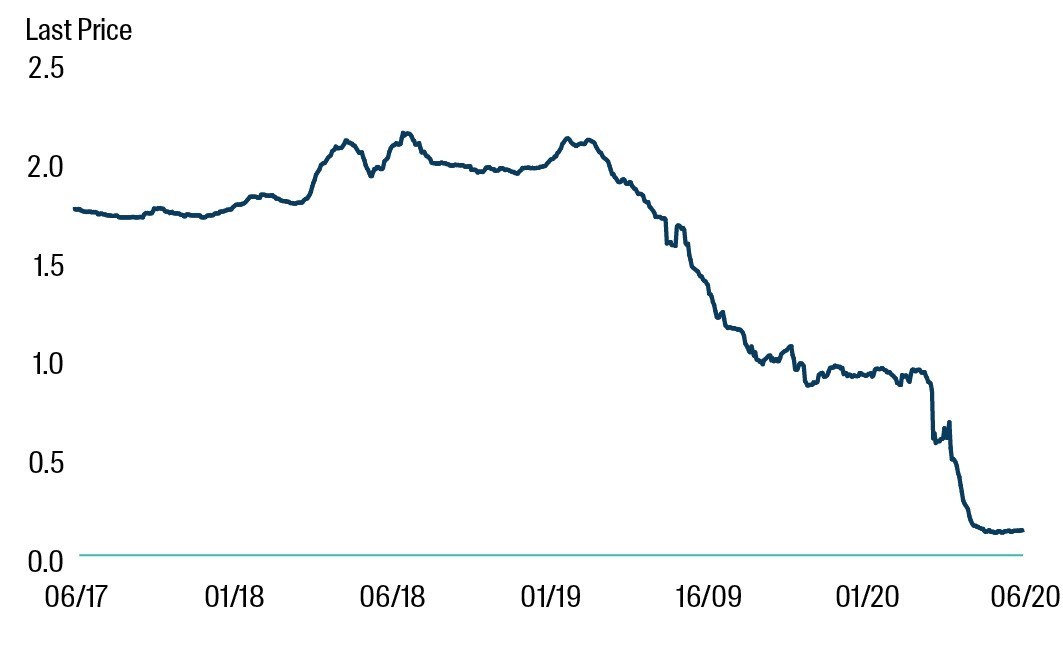

But since mid-March 2020, we have steadily seen these interbank lending yields collapse and fall through the cash rate. For example, the 3-month BBSW rate has fallen to 0.10% (see below). What is so special about 0.10%? It is the rate of interest the RBA is currently paying the banks on their exchange settlement reserve balances as previously described. The result is the clearing yield level for the most common and liquid money market securities has collapsed and there is no additional return for taking on the short-term credit risk in lending to banks.

3-month Bank Bill Swap Rate (BBSW)

Source: Bloomberg as at 15 June 2020

The curious case of Australian Treasury notes

As a quick aside, the Australian Government through the Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) has historically issued very few Treasury notes, or debt securities with a maturity of less than one year. A year ago in June 2019, there was just $3 billion outstanding. To put this in context, this was less than 1% of the Commonwealth of Australia’s total debt. Today, the amount of Treasury Notes on issue has ballooned to $51 billion (or roughly 8% of all Australian Government Bonds on issue). Interestingly, these securities are being issued via auction at levels well above NCDs issued by banks. In other words, the Australian government is paying more for short-term financing than the major banks. NCDs – particularly those issued by the four major banks – are known to be among the most liquid instruments traded in Australia. Despite being tested over various crises, including a near-halt of trading activity in various fixed income and credit markets during March 2020, we have not observed any liquidity challenges in the Australian NCD market.

As one of Australia’s largest cash managers, we believe NCDs are in the short-term likely to provide more liquidity than short-dated Treasury notes.

This is because banks have historically provided a market for their own NCDs where required as they do not want to lose access to this important funding channel. The AOFM, does not make a market itself in its own securities, instead relying on its Tender Panel members (i.e. the banks) to make markets in these securities.

This liquidity difference combined with increased supply of Treasury Notes and the decreased supply of NCDs has created the yield differential. While this differential is the opposite of that seen in a normal environment, we envision it temporarily persisting as long as these technical supply/demand dynamics remain in place. A change will be through a combination of the Australian government slowing down their debt issuance and the RBA deciding to reduce their open market operations. Nonetheless, these relationships are highly unusual, and we think it is more likely that the actual overnight cash rate and bank bill rates will rise back up towards cash rate target instead of falling further. However, this would have short-term implications.

The Bank Bill Index

The most common benchmark for money market products in Australia is the Bloomberg AusBond Bank Bill Index (‘the Index’). The Index is comprised of 13 separate notional bank bills ranging from seven to 91 days in time to maturity, with each security maturing on consecutive Tuesdays. Each day the term to maturity of each security, and hence the index as a whole, reduces by one day until the shortest security matures. The face value of the maturing security is then reinvested in a new security with a term to maturity of three months (or 13 weeks) and the term to maturity of the index as a whole lengthens by approximately seven days.

Generally, one could expect the return of the Index to be an average of the yield on the various short-term securities. However, when rates fluctuate, the market value of the securities changes. Just like any other bond, when interest rates go down, the price goes up, and when interest rates go up, the price goes down. While the interest rate sensitivity of the Index is very low, because of the construction of the Index, it still carries reinvestment risk as securities are maturing every week for three months. The relevant statistic is duration which measures the sensitivity of the price of a security or portfolio to yield movements. While it fluctuates a bit as the Index shortens and lengthens, the duration it is typically around 45 days or 0.125 years. This means that for a 1% or 100 basis point move up in yield, the Index loses 12.5 basis points.

The low running yield of the Index at 0.12% (or 1 basis point per month) means if the Index yield rose by 9 basis points in a given month, from 0.12% to 0.21% (still below the RBA cash rate target), the Index would register a negative return. Here’s the calculation:

Bloomberg AusBond Bank Bill Index:

Yield to maturity: 0.12% (1 basis point per month)

Duration: 0.125 years

Yield rise: 0.09% (9 basis points)

Index price impact: 0.125 * 0.09% = -0.01125%

Index total return for month: 0.01% (running yield) - 0.01125% (price change) = -0.00125%

Example for illustrative purposes only

How Low(e) can rates go?

There is increasing speculation by market participants and the press that Australia may move to a negative interest rate policy. We currently take the RBA at their word and do not believe cash rates will fall into negative territory. Governor Philip Lowe has repeatedly stated that he views 0.25% to be the effective lower bound and has insisted that negative interest rates are “extraordinarily unlikely”. He has recently reiterated,

“I just don’t think negative interest rates work”.

Instead, if the growth outlook were to disappoint the RBA, Lowe said that “if we had to do more , we could purchase more Government bonds”. The RBA is in good company; US officials have made similar public statements about the efficacy of negative rates and suggested such a policy is not currently being considered by the Federal Reserve.

Therefore, we believe it is more likely that the actual overnight cash rate in Australia moves up towards the target of 0.25% as opposed to down to or through zero. Of course RBA officials can change their mind, but there is considerable capacity for the RBA to expand their asset purchase program. Should economic and/or liquidity conditions deteriorate further and fiscal stimulus disappoints, we believe a more expansive asset purchase program would be the likely next option pursued ahead of a negative interest rate policy. It’s worth pointing out that while the Australian cash rate and bond yields are historically low, much of the rest of the developed world is lower and in many cases negative (see below).

Source: Bloomberg as at 15 June 2020\

Outlook – every basis point counts

In the absence of a crystal ball, we think current conditions in Australian money markets will largely persist for an extended period. A small move up in ‘Bank Bill’ yields back towards the cash rate target has the potential to deliver a negative return for the Index in a given month, albeit a higher running yield would be welcomed following that. Additional return can be generated to offset low cash rates, although typically involves taking on additional credit, interest rate, liquidity, and/or counterparty risk. These risks need to be managed with extreme prudence as we do not believe the full extent of the COVID-19 crisis and economic damage has fully materialised.

There are likely to be further bumps in the road before we get back to ‘normal.’

Squeezing every basis point out of the Cash asset class has always been important, but the current market environment demands an active Cash manager proves their worth. Indeed, 0.01% can be the difference between a positive or negative total return. In terms of portfolio positioning, there are various instrument types that add to portfolio diversity (enhancing returns and/or mitigating risk) such as Treasury Notes, Semi-Government Commercial Paper, Convertible Deposit Accounts, Term Deposits, Regional Bank NCDs, etc. For portfolios with fewer constraints, we are looking to pull all the levers at our disposal including short duration credit sensitive instruments (e.g. floating rate notes, AAA-rated residential mortgage-backed securities, etc) which are attractively priced. Further, some clients are seeking other ‘enhanced’ strategies such as allowing foreign Treasury notes or commercial paper, with currency hedged back to Australian dollars.

But here’s the issue with chasing incremental returns when the risk is not attractively priced: most investors hold a cash allocation primarily for liquidity and capital preservation purposes and are not willing to compromise on these features. This is the conundrum we are wrestling with but as seen over the past 30+ years, we typically err on the side of caution.

With respect to liquidity, true cash still remains ‘king’ in Australia.

We will remain active to both protect and enhance returns as the ‘excess’ return delivered by a Fund manager becomes a more meaningful and important component of a cash portfolio’s total return given the low starting point.

For portfolios managed by our Short Term Investments team, we are in active engagement with stakeholders to ensure the investment objectives, vehicle structure, and investment guidelines are set up optimally to manage effectively through this challenging market environment. Further we offer a range of short duration and credit products that may be more suitable for those seeking attractive opportunities or require additional return.

Put your money to work with an active cash allocation

Whether you are seeking diversification for your portfolio, aiming to preserve capital or have short term investment needs, an allocation to cash is likely to complement your investment portfolio. Stay up to date with my latest insights by clicking the follow button below.

1 topic