Is time money? Long-term bonds vs long-term exposure what really matters?

It is commonly considered that investing in longer term maturity bonds allows an investor to capture the full extent of the term premium. However, could it be possible to extract a similar term premium by investing in a series of shorter-term bonds over the same period?

When seeking to earn the term premium available from the yield curve it is useful for investors to appreciate that there is an important distinction between the term of (a) their investment horizon and (b) the bonds being invested in. While such a distinction may seem trivial it has, potentially, important implications for investors. To see why, start by considering that the term premium is normally viewed as the additional return required to induce investors to hold longer duration bonds. The nuance which is potentially missed in such a definition is that the term premium includes the additional return which investors require to induce them to postpone consumption further into the future; i.e. lengthen their investment horizon. For this reason investors can consider that a material portion of the additional return available from the term premium actually comprises a ‘Time Premium’.

Viewing the time premium as the additional return earned for deferring consumption has interesting implications for the best means of accessing the premium. It would appear at first glance, that the best approach is to lengthen one’s investment horizon by buying longer duration bonds. After all, bonds with longer terms to maturity normally form a positively sloped yield curve, and thereby exhibit higher yields. This is where it gets a bit more complex. Simply put any yield curve can be used to calculate the yields of any combination of bonds with differing terms to maturity along that yield curve. This occurs as the difference in yield between any two bonds of differing terms to maturity must imply a yield for a forward bond which equates both the terms to maturity and the respective yields. The yields on these forward bonds are referred to as Implied Forward Rates.

To illustrate consider an investor with a 10-year investment horizon who has a choice of investing in either a 5-year bond or a 10-year bond. Should the investor elect to buy a 5-year bond then they will, after 5 years, have to reinvest in another bond with 5 years to maturity. The yield on this implied 5-year bond starting in 5 years is in turn given by the difference in the 5 and 10 year yields and effectively equates the returns. The result of this equalisation of yields is that in theory, based on any yield curve at a point in time an investor can expect to earn the same time premium irrespective of the tenor of the bond chosen. This highlights that it is the act of lengthening one’s investment horizon which generates the higher time premium not necessarily the actual term of the bonds themselves; i.e. the term to maturity of one’s investment horizon and those of the actual bonds themselves can be considered as separate factors.

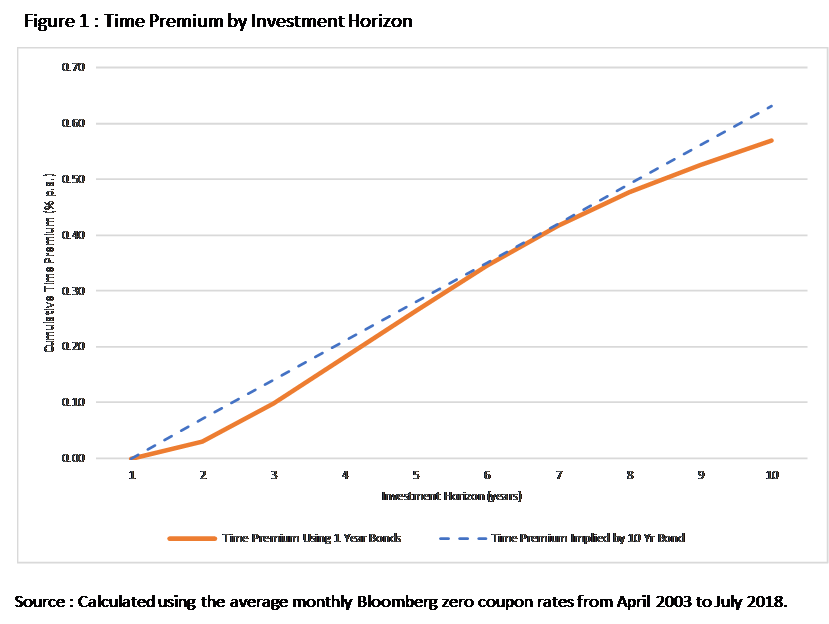

Though in theory such a relationship can hold there is the potential that it may not hold in practice. The reason for this is that there can be imperfections or rigidities within financial markets which may result in yield curves being systematically distorted. To see the extent of any distortions in Australia one can test whether over time (a) the relationship between time premium and investment horizon is linear * and (b) that yields of different tenors are equalised. Testing these two propositions can be done by initially calculating the time premium earned over a 10-year investment horizon by compounding out the returns from investing in a series of 1-year bonds. The resulting time premiums for different investment horizons can then be compared to the time premium implied by a physical bond with 10 years to maturity. If the two premium curves are similar then there is not only a linear relationship with respect to the time premium but also yield equivalence based on investment horizons (see Figure 1).

Though the fit is not perfect, the historical evidence over this period suggests that in practice the time premium is largely linear and there is broadly an equivalence of yields based on investment horizons. With that said it is worth noting that (a) over certain investment horizons the time premium is less than would be expected and (b) over longer investment horizons investors will earn a higher premium from investing in longer tenor physical bonds. Overall, while acknowledging the earlier caveats, it does appear reasonable to conclude that an investor in Australian bonds can earn a material portion of the term premium available by lengthening their investment horizon without necessarily having to lengthen the term of the actual bonds used; i.e. material proportion of the term premium comprises the time premium even after allowing for differences in transactions costs.

This has interesting implications for bond investors:

- While investors can earn a higher term premium by locking in longer duration bonds, the bulk of the higher return, i.e. the time premium, is earned by simply committing to a longer investment horizon.

- The decision regarding whether to buy longer dated bonds shouldn’t be driven by a desire to earn the time premium. Rather the decision to buy longer term bonds should be driven by other factors (as will be set out in a follow up paper).

- Investors have a greater degree of freedom when constructing fixed income portfolios to reflect their preferences. The separation of the term of the underlying bonds from that of the investment horizon provides investors with a greater range of ways to reflect views/preferences while still being confident that they will be earning the bulk of the time premium.

While it may seem counterintuitive the upshot is that earning a material part of the term premium available simply requires investors to be patient and maintain a longer-term exposure to bonds as opposed to needing to maintain an exposure to longer term bonds. This highlights that it is the act of lengthening one’s investment horizon, i.e. deferring consumption for longer, which results in the investor earning a higher term premium over time irrespective of the bonds used. In practice investors may have greater degrees of freedom than they may have initially realised as they are not necessarily forgoing the returns associated with the term premium simply because they are not investing in longer term bonds.

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...

Expertise

Clive Smith is an investment professional with over 35 years experience at a senior level across domestic and global public and private fixed income markets. Clive holds a Bachelor of Economics, Master of Economics and Master of Applied Finance...