Long-term focus can help counter investors' behavioural biases

The volatility in global markets over recent months has left many experienced investors concerned that downside risks are growing. These concerns over market weakness are clearly very valid. But on a long-term perspective, as the founder of modern security analysis Benjamin Graham once said, “The investor’s chief problem – and even his worst enemy – is likely to be himself.”

Investor behaviour can appear to defy all logic and reason. Why? According to research in behavioural finance, most investors are not strictly rational. Rather, they are subject to behavioural biases; past experiences, personal beliefs and preferences can influence judgement and skew decisions. These biases can steer them away from logical, long-term thinking, and deter them from reaching their long-term investment goals.

In this report, we study two common behavioural biases: loss aversion and herd mentality. We examine their impact on investment returns and consider how long-term investing can help mitigate these biases and produce positive investment outcomes.

We believe our research makes a strong case for long-term investing, particularly in relation to buying and holding sound investments. More importantly, we think it’s time to refocus on long-term investing and how it can create meaningful value for the investor.

The truth about ‘buy low, sell high’

The notion of ‘buy low, sell high’ might seem obvious – and simple – enough, but this oldest piece of investment advice is easier said than done. In fact, many investors tend to do the opposite: buy high and sell low.

We don’t have to look hard to find evidence of such behaviour. During the peak of the dotcom bubble in 1999-2000, investors poured close to US$500 billion into equity mutual funds even as markets became increasingly frothy. When the bubble burst, many of them panicked and pulled out at the market bottom in 2002, prompting around US$30 billion of outflows. Those same investors missed out on the subsequent rebound as the Nasdaq Composite surged 50% in 2003.

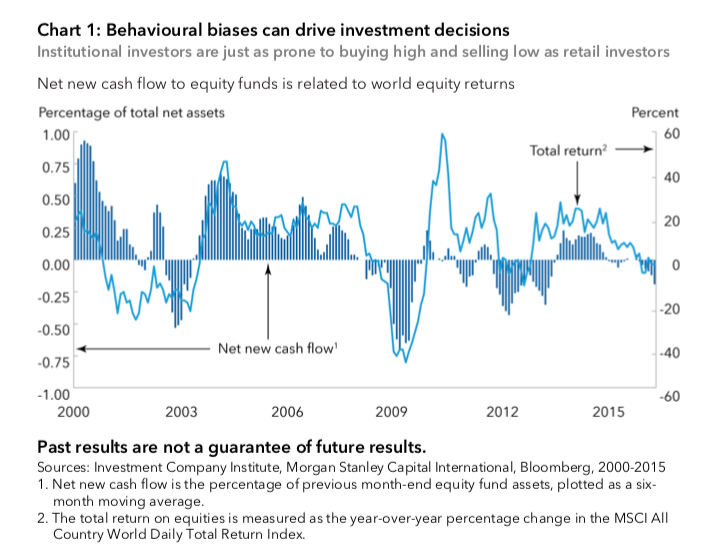

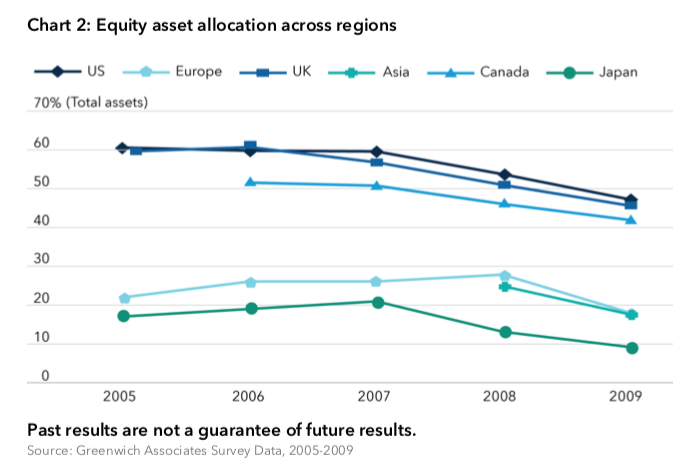

The same happened during the 2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis. As charts

1 and 2 show, investors (both institutional and retail) fled the markets as global stocks plunged 40% between September 2008 when Lehman Brothers collapsed and March 2009 when equities hit their lowest levels. In short, investors often jump in and out of markets at the worst possible moment. Why do they fall into such behaviour traps?

Behavioural pitfalls

Behavioural finance contends that when it comes to investing, people often exhibit herding behaviour or a ‘group think’ mentality. They mimic the behaviour of others, especially in times of uncertainty. But the majority is not always right. Besides, basing one’s investment decisions on the actions of others makes little sense, in our view, given investment goals and financial circumstances can vary.

Most investors are also loss averse. According to research by Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman and his late collaborator Amos Tversky, losses hurt about 2–2.5 times more than gains satisfy. Put another way, the pain of losing US$10,000 is disproportionately greater than the pleasure of winning US$10,000; most people need a potential gain of around US$20,000–US$25,000 to balance the risk of losing US$10,000.

This asymmetry could lead to panic selling during severe market setbacks.

A litany of news stories (often negative) from round-the-clock news channels, the internet and social media can exacerbate investors’ emotions, making these behavioural biases even harder to overcome.

Effects of loss aversion and herding on investment returns

If behavioural biases can influence financial decisions, what is the potential impact on investment returns? We sought to answer this question by studying the effects of loss aversion and herding on investment returns.

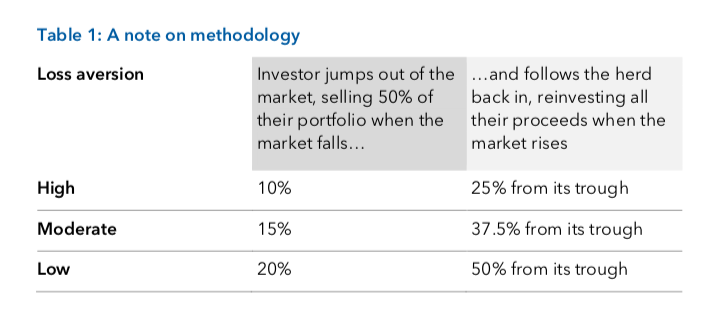

To be as comprehensive as possible, we analysed multiple scenarios using a loss aversion ratio of 2.5 times and covered a total of 337 rolling periods. For the purpose of this study, we focused on three scenarios (as outlined in table 1): investors with high, moderate and low loss aversion, leading to high, moderate and low trading frequency respectively, which we compared with a buy-and-hold scenario.

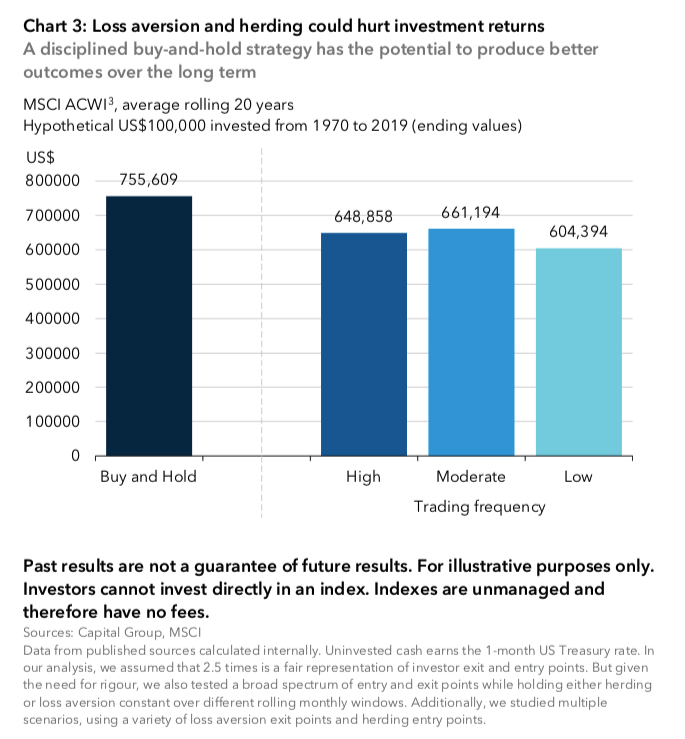

The results are striking. According to chart 3, buy-and-hold investors could earn better returns compared with those who move in and out of markets.

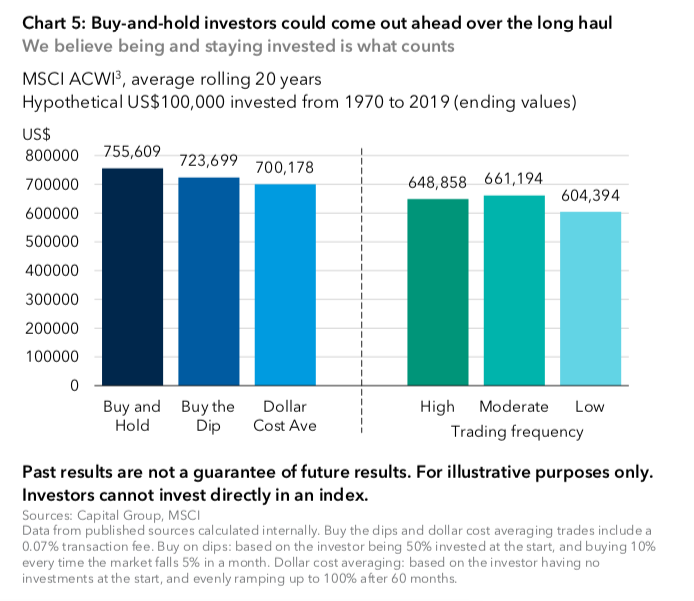

Over the average 20-year rolling period between 1970 and 2019, their initial investment of US$100,000 would have had an ending value of US$755,609. By contrast, highly loss averse investors would have gained US$648,858, or 15% less.

The bottom line: behavioural biases could lead to investors lagging their buy- and-hold counterparts and hinder the creation of long-term value.

That is not entirely unexpected. Buying and holding investments for the long haul not only helps investors take advantage of the power of compounding, but it can also mean saving money on transaction fees and may offer tax benefits in certain countries. Choosing the right investments, as we demonstrate later, can make a big difference too.

The cost of getting out and staying out of the market

Market corrections of 10% or more are not uncommon. The MSCI ACWI, for example, has had 40 such declines since 1970. When investors see the value of their investments dwindling, their aversion to losses can compel them to sell at a loss and stay out of the market. But that can cost investors dearly over time. Why?

Because stock markets tend to have a reassuring history of recoveries – though no one can predict how long a decline will last. After the 1929 Wall Street crash, for example, it took investors 16 years to recoup their investments if they had bought at the height of the market. However, since 1982, with a few exceptions, market declines have been relatively brief. In 1990, it took about 8 months to get back (4).

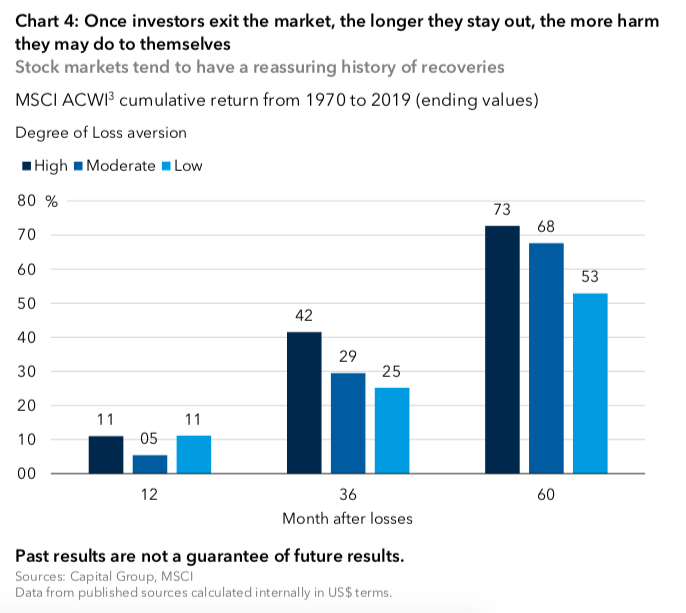

Our analysis, with data from 1970–2019, looked at returns 1, 12, 36 and 60 months after an investor leaves the market. While there was little meaningful impact one month later, chart 4 shows that the consequences were significant one, three and five years down the road.

For instance, a highly loss averse investor who rushed for the exit when the market dropped 10% would have, on average, missed a cumulative return of 73% five years later. Investors with moderate or low loss aversion would have fared no better: because they got out and sat on the sidelines, they could have missed rebounds of 68% and 53% respectively.

We also sought to look at the same issue from a different perspective. We kept loss aversion constant and examined a wide spectrum of re-entry points over a 30-year period.

The conclusion remains the same: the longer the investor waits to re-enter the market, the more damaging the potential consequences. In short, staying invested can help produce higher returns.

Should investors buy on dips or dollar cost average?

Of course, buy and hold is not the only investment strategy available. Some investors adopt a ‘buy on dips’ approach, where they purchase stocks following a decline in prices. Another strategy is dollar cost averaging, which involves investing a fixed sum of money at regular intervals over a period of time.

How do the latter two strategies measure up to the high, moderate and low trading scenarios described earlier over a 20-year rolling period between 1970 and 2019?

Chart 5 indicates that buying on dips and dollar cost averaging compared favourably to moving in and out of the market. In our example, the two approaches produced better end-investment values of between 6% and 20% higher. That said, they fared less well than buy and hold.

One problem with the buy on dips approach is that investors have unspent cash or ‘dry powder’ that earns low returns. Other issues include market timing, which can often be counterproductive, and trading costs.

Dollar cost averaging ignores market timing and can help smooth out the market’s ups and downs, though it faces the same issue of higher transaction costs. And by spreading out investments over a long period, investors spend less time in the market compared with buy-and-hold investors, who are fully invested for the entire time.

Simply stated, time in the market matters. If investors have funds upfront, in our view it is better to put more of it to work earlier on than try to second-guess the market’s movements. Not only can it potentially build returns over the long term, but it also helps circumvent behavioural biases.

The case for selectivity

Buy and hold could yield greater value over the long term – that is the conclusion drawn from our analysis of market returns over the past few decades. This is easier said than done, however, which is why it is important that there are certain portfolios designed to reduce downside risk and lower volatility. These types of portfolios can help calm investor nerves when markets turn turbulent.

It helps, therefore, that there are skilled investment managers that are focused on downside resilience and low volatility, both of which can help counter behavioural biases. Passive index investors, by contrast, bear the full brunt of market declines.

That is also why we stress a long-term perspective and the importance of preserving capital during downturns. We believe that by producing results that are less volatile than the broader market, investors are less likely to react to fluctuating market conditions by making short-term decisions with potentially destructive long-term consequences

Summary

Behavioural biases such as loss aversion and herd mentality can play a big part in investors’ decisions and can make a dramatic difference to investment returns. Analysing three scenarios (investors with high, moderate and low loss aversion, leading to high, moderate and low trading frequency respectively) and comparing them with a buy-and-hold scenario has yielded valuable (if somewhat expected) results:

-

Buy-and-hold investors could earn better returns compared with those who move in and out of markets.

-

Once investors exit the market, the longer they stay out, the more harm they may do to themselves.

-

Time in the market matters: being and staying invested is what counts.

Perhaps more importantly, these conclusions raise a bigger question: How can investors, given their behavioural biases, stay focused on their long- term investment goals? We believe that portfolios with downside resilience and lower volatility can help protect investors from making irrational decisions. That is where skilled investment managers can add value. We think investors should seek out strategies with a track record not only in up markets but also down markets, and that they are likely to be rewarded for their patience.

Position your portfolio to navigate through cycles

Capital Group believes in a smarter way of investing that combines individuality and teamwork into a tailored approach to help investors meet their goals. Find out more by clicking 'CONTACT' below.

1 contributor mentioned