September Review: Calm Conditions on the Surface

September was a mostly flat month for risk assets, with credit and equities not doing much whilst commodities mostly rose. Equities in Australia (0.1%) and the US (-0.1%) barely moved. There were small losses in Europe (-0.7%), China (-2.2%) and Japan (-2.6%). Credit was also flat with the roll of investment grade indices pushing those up. US oil jumped 7.6% on speculation that OPEC might cut production with copper (6.4%) also strong. US natural gas (1.0%) and gold (0.5%) rose a little whilst iron ore fell 4.4%.

There were a few ups and downs in September but it was largely a case of calm conditions on the surface. However, below the surface there’s a plethora of potential problems. Various writers put forward their views on what is the biggest risk facing the global markets and economy. Economist Ken Rogoff sees China as the biggest risk. Stephen Roach sees central bankers as a big risk as they double down on failed policies. The Germans are talking up the risk in Italian banks and are calling the upcoming Italian referendum the biggest political risk. George Friedman called Italy “the mother of all systemic threats”.

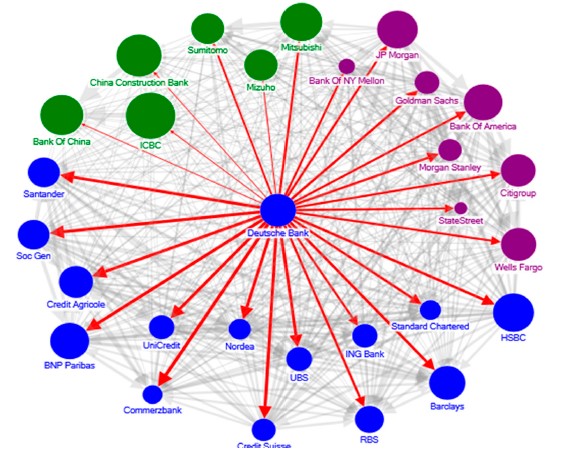

The Italian Prime Minister is pointing right back at Deutsche Bank. The FDIC has the bank as the number one risk and an IMF June report concluded that it was the number one systemic risk. The graphic below from that report illustrates just how interconnected Deutsche Bank is with other major banks. Mario Draghi sees Europe’s large number of small banks as Europe’s biggest problem. Take your pick, there’s plenty of things that could start a global recession and market sell-off. Arguably the biggest risk is that one problem takes hold and it triggers the others.

Source: IMF

Bad Banks

Deutsche Bank continues to attract comparisons with Lehman Brothers. At first it was just the share price comparison that has both tracking ever lower, but now Deutsche Bank is making the same sort of reassurances about solvency and liquidity that Lehman’s CEO and CFO did in the year before its collapse. The credit default swaps are at levels that might start to worry its counterparties and the contingent convertible securities at back in the low 70’s. The news that hedge funds are moving their prime brokerage balances from Deutsche Bank could start a liquidity crunch. Hedge funds are known for herding and there is no upside in keeping your capital with a bank that has doubtful solvency.

The announcement early in the month that Deutsche could be facing a $14 billion fine for mortgage backed securities started the ball rolling. Deutsche Bank has said it won’t be settling for anywhere near $14 billion, but it has all but conceded it will be paying something meaningful. The bank only has $6 billion in legal reserves and there’s a backlog of other litigation matters that will cost something to clear. The comments by Angela Merkel that the government won’t provide assistance to Deutsche Bank further rocked confidence, although the government is reportedly preparing contingency plans.

The primary problem for Deutsche Bank remains that it is woefully undercapitalised. Unlike its larger American counterparts it hasn’t raised enough equity since the crisis to satisfy regulators and the markets. Whilst it has balance sheet equity is €66.8 billion, of which €17.6 billion is intangibles and deferred tax assets, its market capitalisation is only €16.2 billion. Using the regulatory view of its equity position, its assets are 41.4 times its core equity. Its assets are also 111.3 times its market capitalisation.

To get to a 5% leverage ratio requires another €27 billion of equity; a sale of the asset management business might raise €10 billion. A share raising of more than the market capitalisation seems unlikely as there simply isn’t comfort around the quality of the assets. Investors will struggle to see meaningful profits ahead as the bank has recorded a cumulative loss of €1.88 billion over the last four and half years. Based on a high level political and financial analysis a bail-in of senior debt, subordinated debt and preference shares is a realistic possibility. Investors in these forms of capital should ignore the reassurances on liquidity and focus on solvency and profitability.

Further along that road is the Italian bank Monte Dei Paschi. The prospects of a €5 billion equity raising and a €28 billion sale of non-performing loans are fading fast with the equity raising now forecast for next year. Discussions are being held on voluntarily converting subordinated debt to equity. The recapitalisation plans stalled as the CEO was sacked, his replacement is a former CFO of the bank who was fined for falsifying the accounts.

There’s something of a gulf emerging between US and European banks and their regulators. US banks aren’t doing too badly lately but most European banks have fallen substantially this year. The US regulators are pushing ahead with plans that require more capital to be held against equity and merchant banking activities. The US Comptroller of the Currency noted that now is not the time to reduce capital, something the Bank of England has just allowed. The US is pushing for tougher Basel 3 rules, the Swiss are already implementing them but the EU is pushing back. The CEO of Credit Suisse noted that European banks are in a “very fragile situation” and are “not really investable as a sector". He sagely advised “in life you should only worry about the bad outcomes. If you raise capital and you're wrong, it's ok. If you don't raise capital and you're wrong, you die”.

Yield Chasing

The chase for yield continues to be a strong theme as investors search for ways to get higher returns. Issuance of payment in kind (PIK) securities is back to the peak levels of 2007, although this time around the securities tend to be from higher rated issuers. One week there was a surge in issuance, the next week two of the securities issued in that surge were down by 2.8% and 4.5%. The US ABS market is also seeing bumper issuance, particularly in CLOs. Sales of additional tier 1 instruments have spiked in August and September.

The weak supply of leveraged loans is seeing covenant levels falling yet again, with maintenance covenants (a key protection for lenders) now less common than at the last peak. The risks of cov-lite lending is becoming apparent as this default cycle increases, with Bloomberg pointing to examples of lenders stuck as passengers as borrower debt levels soar. Similar to their US and European cousins, yields on Asian high yield bonds are at record lows.

In another lesson for credit investors, Samarco has elected not to pay interest on its bonds. I suspect many investors would have bought these bonds taking comfort that the joint venture is owned by two of the largest miners, BHP and Vale. Neither has guaranteed the debt though, so there’s limited consequences for them in Samarco defaulting. This is three-way battle as the government is seeking compensation, creditors are seeking a recovery of their debt and the joint venture partners are seeking to limit their losses. Bondholders have a very weak hand in these negotiations; without the help of the government and the joint venture partners the mine won’t restart. If the mine remains closed the recovery rate will be negligible.

Pension Funds

Pension funds continue to be a slow burning issue, but news this month highlighted the problems and potential end game. California’s pension problems are amongst the worst in large part due to a 1999 decision to massively increase benefits paid and decrease the age at which retirements benefits start. The sales pitch at the time was that the great returns being achieved on investments would fund the generous promises without additional government funding. After the decision investment returns have slumped, forcing the state to increase contributions. Even with greater contributions the underfunding gap continues to grow. Other state and local governments are being forced to increase contributions as pension schemes are lowering their future return expectations.

The gap between what some pension plans say they are going to earn and what they are likely to earn was highlighted by a small pension plan managed by Calpers. When the local government sponsor decided to cease contributing on the apparently fully funded plan Calpers asked for substantial additional capital pointing to a much lower set of return expectations. If a company was running two sets of books it would be considered fraud or tax evasion.

The end of the road for underfunded pensions is playing out in Dallas where the police pension plan is being hit with a wave of full withdrawals. This is the equivalent of a run on the bank. As exiting members receive 100% of the current value of their benefits paid immediately, remaining members see the percentage of their future benefits covered by assets drop precipitously.

For pensions there’s also the risk that another financial crisis will see a broad based sell-off of assets, blowing out the underfunding gap. When this occurs, don’t be surprised if a wave of government bankruptcies follows. It will also become a ballot box issue as those with generous pensions will be up against the majority of citizens that are being asked to pay for these pensions through much higher taxes. For some it’s already happening with Chicago residents set to be hit with a 33% increase in water and sewer levies over four years to fund pension plans. Corporate pension plans are in the worst shape in 15 years with an average funded level of 76%. In the long term that will reduce reinvestment and dividend levels, dragging down shareholder returns.

Central Banks and Monetary Policy

A few months ago the commentary on central banks and monetary policy was dominated by calls for helicopter money. September has seen a substantial turnaround. A former Fed economist criticized “the Frankenstein lab of monetary policy" and warned of a popular revolt against central bankers. Increasingly people are saying that extreme monetary policy isn’t working. Janet Yellen is copping it with comments from noted investors like; “I think she is creating a serious bubble where serious pain is going to come” and “Yellen can’t admit the bubble that’s right in front of her”. After the tech bubble in 2000 and the subprime bubble in 2007, elevated asset prices in 2016 are being called the central bank bubble. Paul Singer noted how central bankers didn’t listen before the last crisis and they are not listening today.

The criticism of academic macroeconomists has been brutal. Mainstream macroeconomics is disregarding facts, preferring unrealistic models. Economists fail to take politics into account when making policy recommendations. It’s time to throw out mainstream macroeconomics and its junk models. Mainstream economics is stuck in a time warp, fighting the last depression not this one. There’s a dangerous cult in academic macroeconomics. The recommendation from the critics is to stop using central banks tools that long ago ceased being effective.

Funds Management

There’s been a surge of articles in the long running debate about active versus passive funds management. It was kicked off with a paper by Sanford C Bernstein & Co that posited that passive investing is worse than Marxism. Their argument is that passive investing doesn’t participate in capital allocation decisions that are critical to economic advancement. In this view, passive investing leaches off the work done by active managers.

The counter is that active managers leach off investors as more than 75% of active equity managers underperform their benchmarks over the long term. That’s simply not sustainable, investors will vote with their feet and that’s how capitalism works. The biggest flows in funds under management this year have been to Vanguard, the world’s largest passive manager. Vanguard’s founder, John Bogle, believes passive’s share could grow to 50-60% before markets would notice. Active management isn’t dead, but high fees without outperformance might be.

The trend against high fees is also hitting hedge funds. Several mega funds are either shutting or downsizing as a result of investors pulling funds after poor returns in recent years. Brevan Howard is one of these and it has offered existing clients no management fees on any new funds they add. Bridgewater is the one mega fund to have bucked the trend adding $22.5 billion in the last year. Surprisingly, it has done that whilst the performance across its funds has been mixed, some up and some down. Liquid alternatives are also seeing redemptions as they have delivered low returns and high fees. Investors reducing their fees is a good thing, but the events at Harvard shows that it can be taken too far. Harvard’s endowment has gone from being one of the best performing to one of the worst performing after it changed managers predominantly to reduce fees.

Another recent trend is the automation of investing. More fund managers are running style and factor models to determine what assets they should own. There’s two key problems with this approach. Firstly, investment returns almost always turn out to be better in back tested models than reality. Secondly, as many investors adopt the same approach the alpha is competed away and overcrowding becomes a problem. Low beta and high dividend stocks are obvious examples. As one old head put it “black box models eventually blow-up, the key is knowing when to turn them off”. Renaissance Technology seems to have got that right, LTCM didn’t.

China

The China Beige Book survey is one of the most in-depth reviews of the Chinese economy that outsiders can get. The latest review aligned well with other data finding that the old economy sectors like infrastructure and property had lifted on the back of debt stimulus. New economy sectors like retail and services aren’t doing as well. The president of the survey company noted “this is not a stable economy. It’s one that twists and turns and happens to end up at the same spot. There are real problems below the surface.” Reports that the government is running a 10% fiscal deficit, on top of the debt to GDP gap of 30.1%, are good reasons to conclude that the economy is not stable.

The key issue for China it still too much debt used for bad investments. The Wall Street Journal compared the growth in debt levels to Star Trek, going out into the unknown. Bloomberg sees a lot of similarities to Japan’s property bubble. A Chinese billionaire property developer called his country the “biggest bubble in history”. Bank of America says a crisis could happen any time noting it is impossible to grow out of this debt. Nomura sees the only option as a wave of defaults. The bad investment is shown best in the state owned entities which are a huge part of the economy but are barely profitable.

Regulation

With only a few months in the year to go Wells Fargo has hit the lead in the competition for the dumbest financial scandal of the year. Wells Fargo has fired 5,300 employees, 2% of its workforce, for opening over 2 million bank accounts and credit cards without client permission. It has been hit with $180 million in fines so far, but there’s the potential for more fines as well as compensation claims by customers and former employees.

A typical financial scandal has three components: a small group of people commits morally grey actions that have the potential for them to earn a large pay-off. The group should be small to limit the possibility of media and regulator attention. The actions shouldn’t be obviously wrong and easily proven, but rather something grey like insider trading or dealing with dubious characters via front companies. Lastly, the actions should hold out the prospect of a large pay-off to be worthwhile compared to the risks. The Wells Fargo scandal is so stupid as it fails all three components.

With 5,300 employees and hundreds of thousands of customers caught up, exposure was inevitable. Systematically firing employees who call the misconduct hotline is another way to guarantee the sham is exposed, the fired employees having nothing to lose and a lot to gain by taking their grievances to the regulator. Forging signatures on account establishment forms and charging customers for services they declined is criminal, there’s no grey area on that. But strangest of all is that Wells Fargo had no prospect of ever making a profit from the misconduct.

Wells Fargo employees likely spent over a million hours filling out paperwork for the bank to collect a measly $2.6 million in additional fees. As well as the staff time, there’s the cost of systems, the bank statements and the cards that go with the accounts. The accounts had no money in them and the credit cards had no spending on them so there was no ability to earn net interest margin.

The reason Wells Fargo staff went to all this effort was to meet a cross-selling goal of eight products per customer. Why eight products? The CEO decided that number because eight rhymes with great. I understand cross-selling and the concept of increasing your share of the customer’s wallet. However, the aim should be to sell profitable products and not to just load up your customers with things they don’t want that cost you money.

The CEO and the former head of retail banking are giving up $41 million and $19 million in stock based remuneration. The CEO is likely to be fired in the coming weeks and the former head of retail banking left in July. Both will keep far more than they have given up and are arguably the least-worst off. Employees who were fired for the misconduct are suing and the whistleblowers who were fired will most likely end up being compensated, either by the regulator or by settlements with the company. Wells Fargo has thrown away its halo, no longer able to claim that it is the honest alternative for banking. It’s also lost its place as the largest US bank by market capitalisation after its shares fell after the scandal broke. Is it any comfort if they win the award for the dumbest financial scandal of the year?

The SEC’s whistleblower hotline is working overtime, receiving over 4,000 tip-offs last year. Since establishment in 2011 the program has paid 34 whistleblowers a total of $111m in rewards. The former head of the SEC’s whistleblower program is now working in the private sector helping individuals see that their tip-offs are acted on and rewarded. One study found that whistleblowing is best received by companies when it is leaders calling out the bad behaviour rather than juniors.

Written by Jonathan Rochford for Narrow Road Capital on October 1, 2016. Comments and criticisms are welcomed and can be sent to info@narrowroadcapital.com

1 topic