So bad it's good?

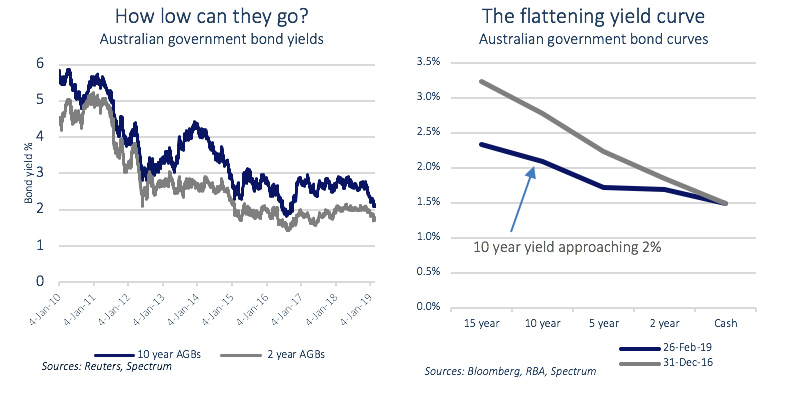

International and domestic economic indicators have turned negative in recent months. Major central banks responded to this and the weak financial markets in late 2018. In fact, policy makers pivoted from “tough love” talk to hints of investor friendly intentions. The central bank “put”(1) lives. Global markets rebounded as a result. The world of negative yield bonds is thriving again. Australia following the trend and now most of the government bond curve is under 2%.

The silver lining may be a quest for yield, pushing down corporate credit spreads further, resulting in more modest capital gains for investors. Or in other words, the news is so bad, the dovish central bankers could help boost returns for A$ corporate bond investors – at least in the near term.

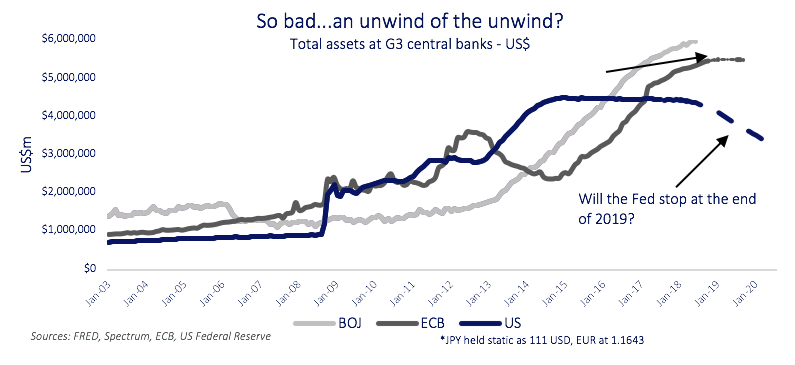

We use the central bank asset graph below to provide an insight into what supported asset prices in recent years and what headwinds the market could face in the future.

Until recently, the accumulation of assets by central banks, known as quantitative easing, looked like peaking in 2018 at around $US12t.

As quantitative easing was to unwind it would allow some asset prices to fall towards levels not influenced by the central bank buying.

That was then.

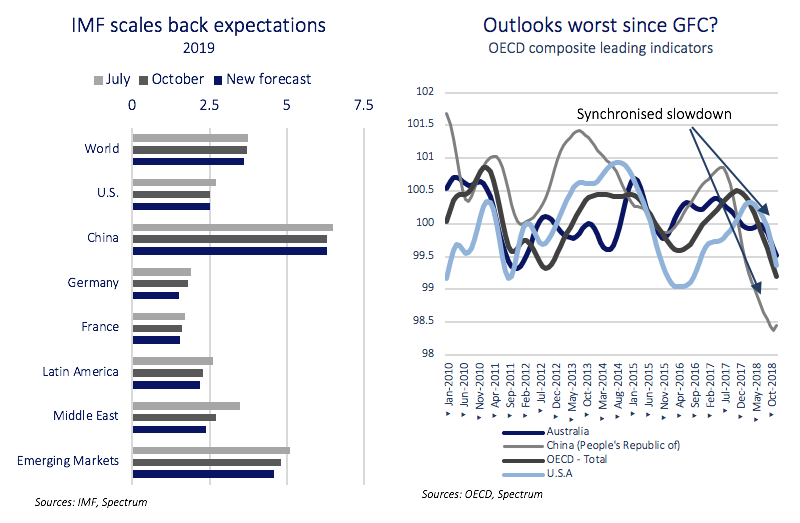

As the graphs above suggest, global economic growth indicators have recently plummeted. Now it looks as though there could be an unwind of the unwind of quantitative easing in the U.S. The previous path of more rate hikes is also disappearing. Indeed, now the market is expecting the U.S Fed to cut rates by early 2020. The ECB’s and BoJ’s policy rates look stuck at negative yields for a prolonged period.

The pile of negative yielding bonds is climbing again. The Wall Street Journal reports negative yielding bonds jumped 21% since October 2018 to reach around $US11t at present.

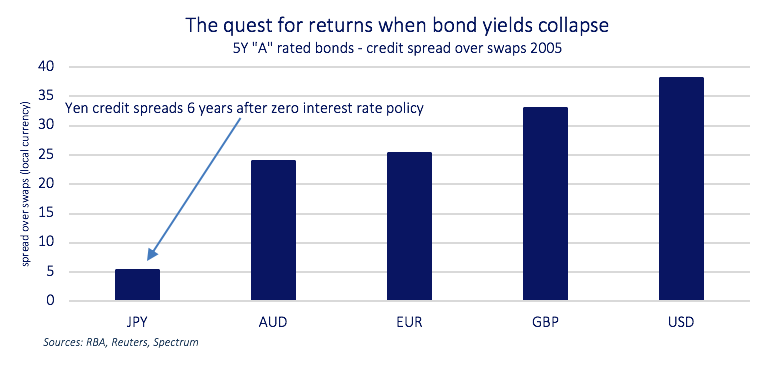

The growing scarcity of positive return investments is pushing investors to chase riskier investments around the world at ever rising prices.

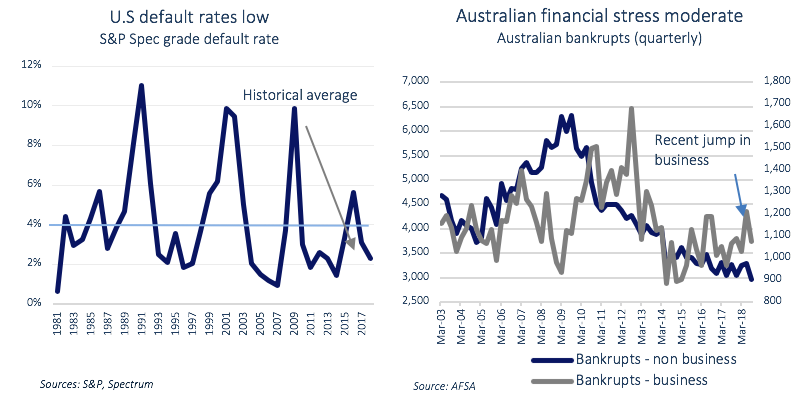

Lower yields not only can cause investors to chase credit risk. Lower interest rates also make it easier for borrower to service debt. Hence widespread financial distress may be kept at bay. In turn, absent default fear, yield hungry investors may chase credit spreads to ever narrower levels.

The same phenomenon was apparent in Japan in the early 2000s. Following the fall-out from a multi-year boom the Bank of Japan slashed interest rates to zero in 1999. Credit spreads collapsed after to settle and remain at levels well below similarly rated peers internationally.

Locally, fears are mounting that a softening residential property could send the local economy into reverse. If this happens, the RBA may well cut the already record low official rate of 1.5%. In turn Australian government bond yields could fall even lower. An Australian 10-year government bond at 1.5%, unthinkable in the past, is now not a far-fetched idea.

We may not agree with the long term economic and financial impact of actions taken by central banks in recent times. But our job is not to adjudge what policy should be. The role is to assess likely financial asset performance and manage the risks within our market.

Global and local government bond yields may remain low for a prolonged period. If so, local credit spreads could contract far below historical averages – and produce moderate capital gains for investors. So, economic conditions may be so bad that they are good for A$ corporate bond investors – at least for a period. A key performance factor may be to avoid the fallout from the driver of lower local bond yields - the Australian residential property market.

______________________________________________________________

(1) The “put” refers to option terminology whereby an investor has an option to sell an asset at certain price. The link to central banks refers to a period in the late 1980’s and 1990’s where it was seen the central banks would take market positive action if risk assets fell in value. Or in other words, investors termed it as meaning the central bank would set a price floor or a strike price for investors to sell assets