The case for energy

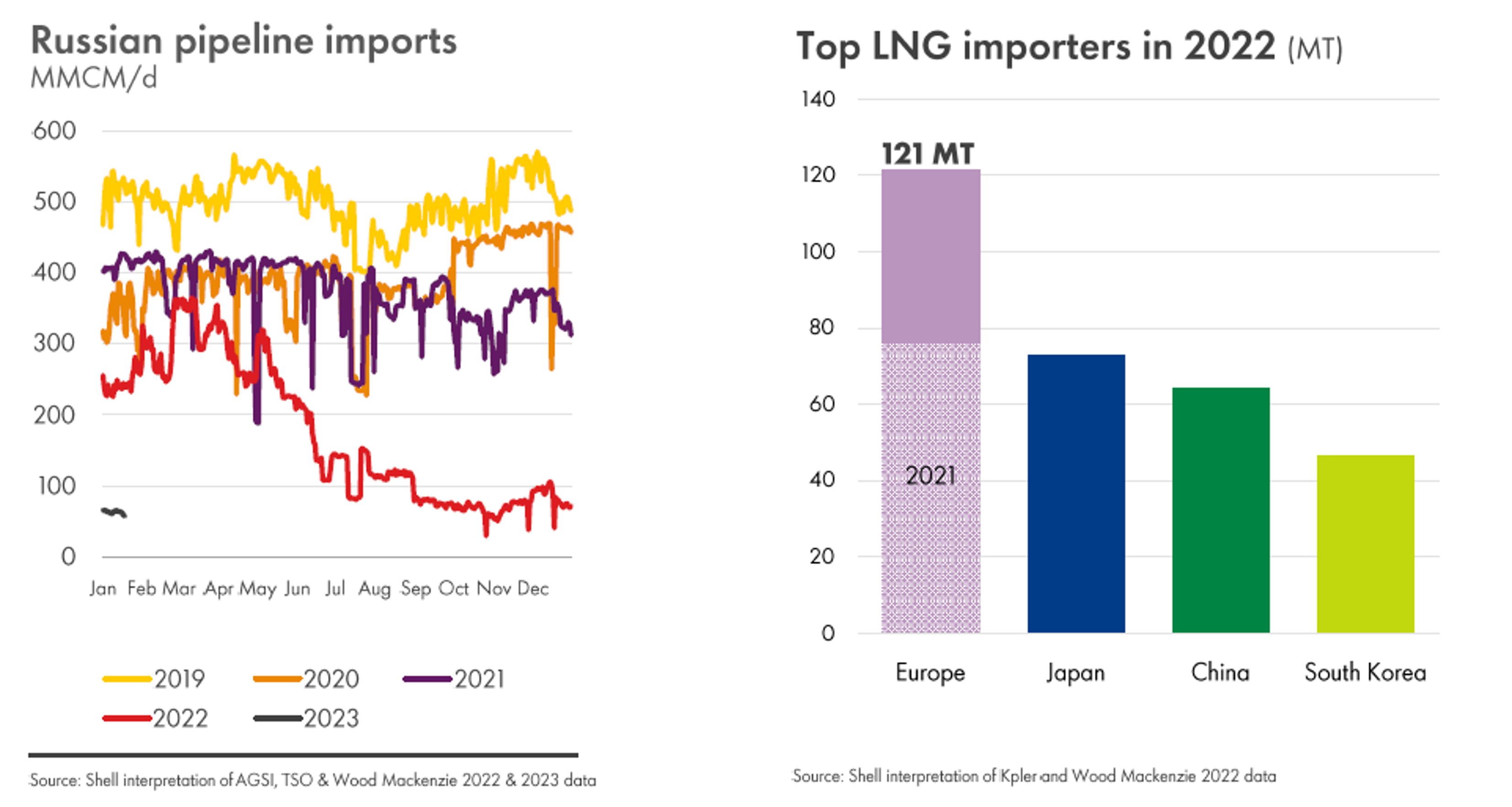

The invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is exposing the fragility of the global energy complex. Piped natural gas from Russia to Europe was disrupted and liquified natural gas (LNG), which shipped by sea, was the substitute. Europe quickly became the biggest LNG consumer in the world. The energy markets tightened, and electricity prices skyrocketed. Under sanctions, Russian oil originally bound for Europe was diverted to Asian countries which refined them into end products like diesel, gasoline and jet fuel. This meant that while the supply of energy did not collapse despite the sanctions, it highlighted the issue of energy security.

As a result of the high gas prices, both wealthy and poorer nations turned to coal for power generation, as it was a more affordable alternative. This shift was not limited to developing countries but also occurred in Europe, leading to a decline in air quality. This setback in access to natural gas has temporarily slowed down progress towards achieving carbon neutrality.

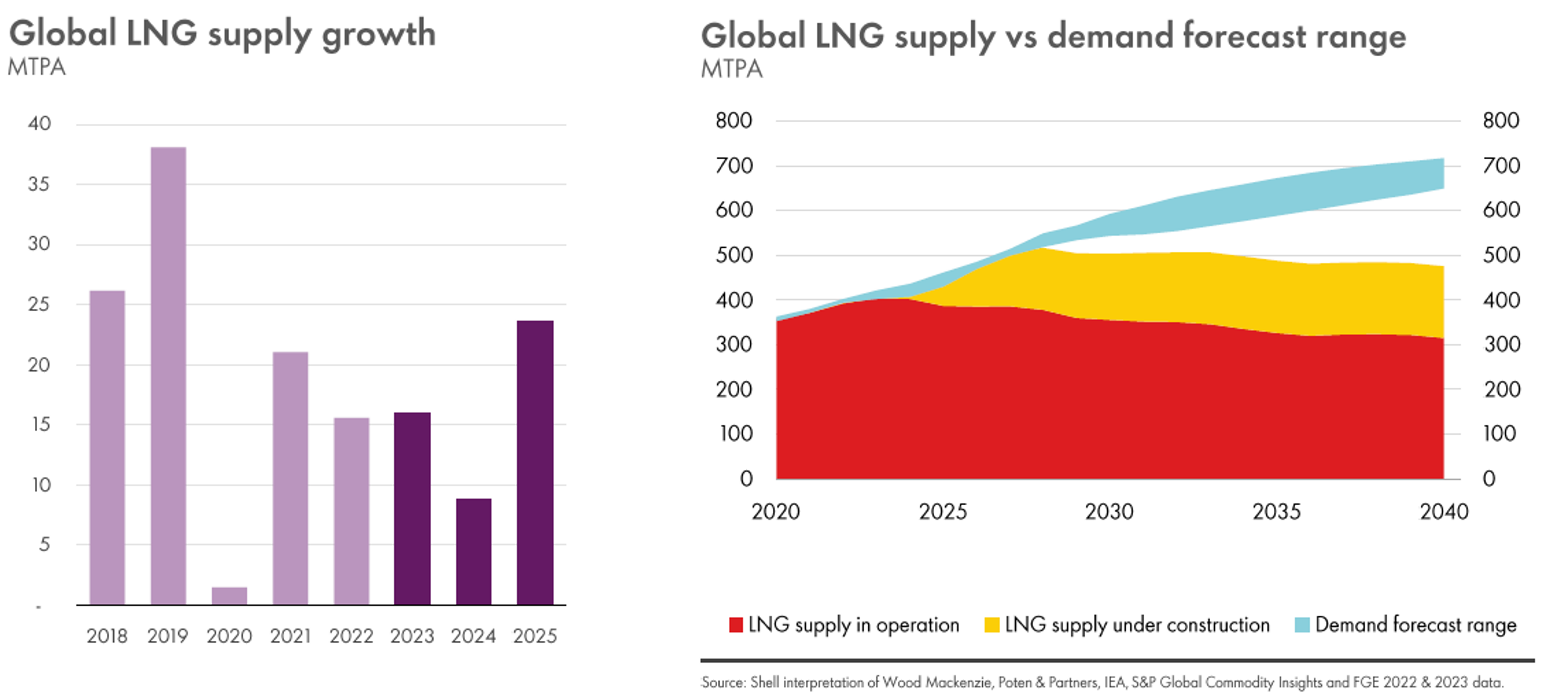

The functioning of the modern global economy heavily depends on energy, and as developing economies, particularly in Asia, continue to grow, the demand for energy will only rise. The fact is, we need a source of energy to ease our transition to carbon zero. The supply side remains less than enthusiastic. Russia continues to shrink its supply, and investment in new production capacity is still being curtailed. This will provide long term support for energy prices.

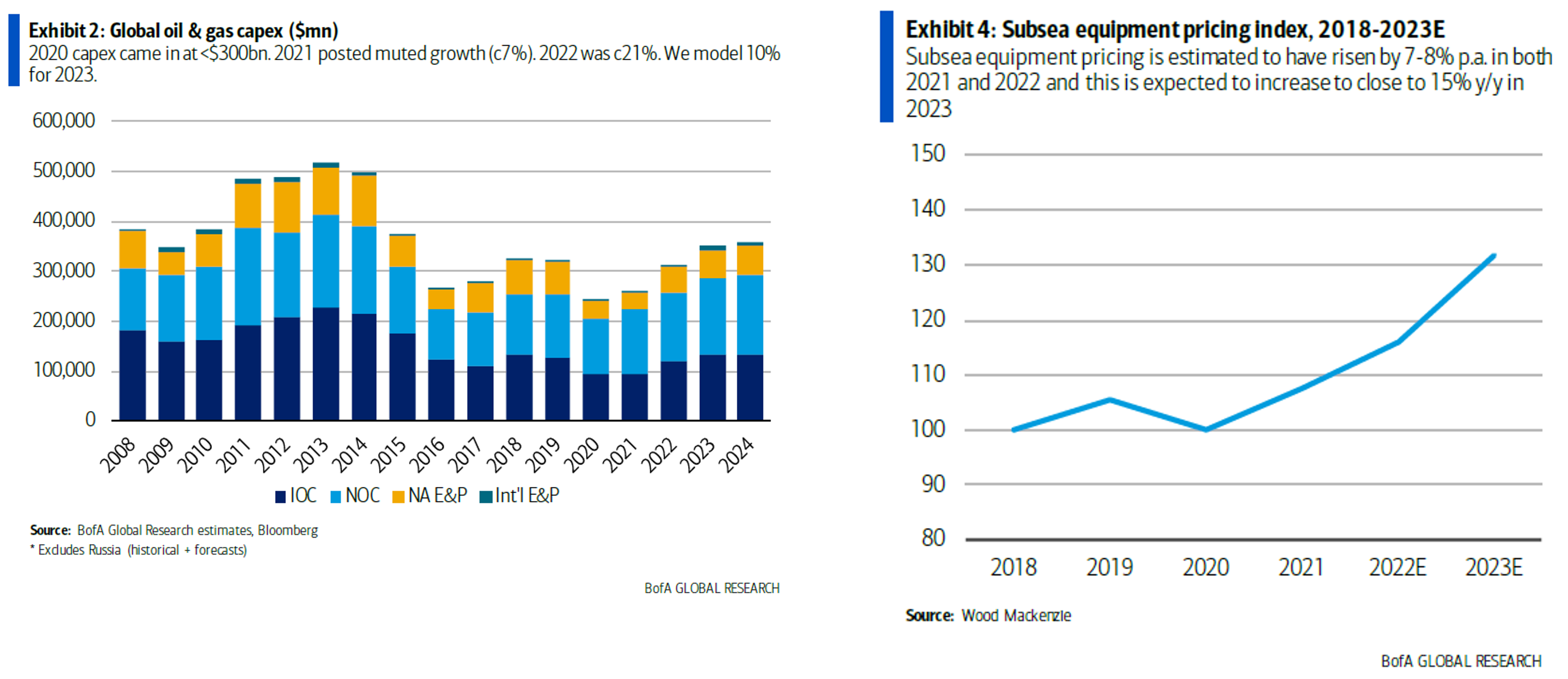

Globally, total investment in the energy sector has fallen significantly in the past decade. At the same time, offshore equipment costs have gone up by 30% since 2020. The reality is that development investment increase in 2023/24 will not be able to meet the world’s increasing energy needs, let alone be producing slack in system to bolstering the capacity to flex supply.

The sense of complacency over energy price is perhaps a result of weak prices despite a decline in investment. The reality is that global oil supply has been underpinned by large greenfield projects in Canada, Brazil, and Norway that were sanctioned in 2010-2014. The drastic reduction of new investment dollars going into the industry will likely lead to supply shocks in coming years.

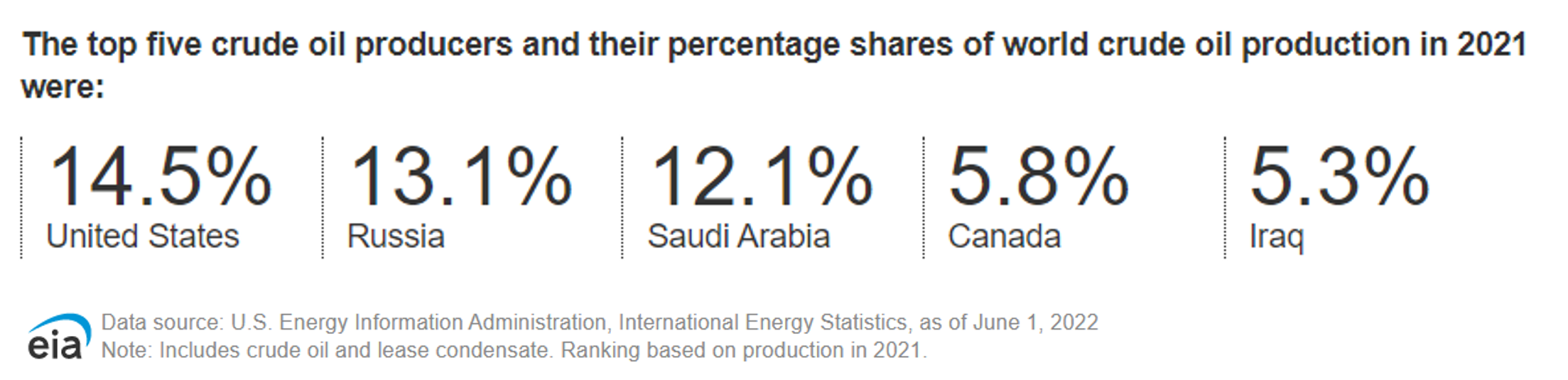

The key oil producers in the world are the USA, Russia then Saudi Arabia. We will go through each of the country in turn.

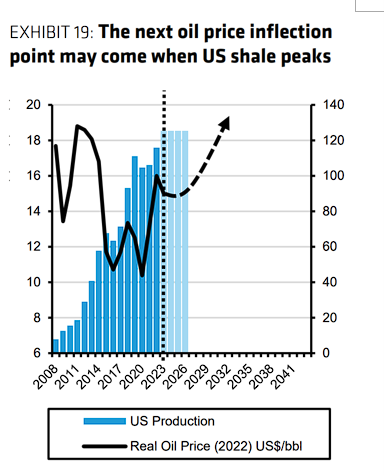

The rise of shale production has turned US from an oil importer to an oil exporter with shale production doubling since 2014. The drawback for shale is that decline rate tends to be much steeper, around 30%+ a year. As a result, the marginal cost of production is typically higher. The best and lowest cost shale resources may have already been utilized. Some traditional shale regions like Eagle Ford and Bakken failed to lift production in 2021/2022. The US shale production is expected by some market observers to peak by the middle of the decade. In previous cycles, oil price reacted enthusiastically upwards when major incremental supply source peaked. US shale production is expected to peak in 2024/2025.

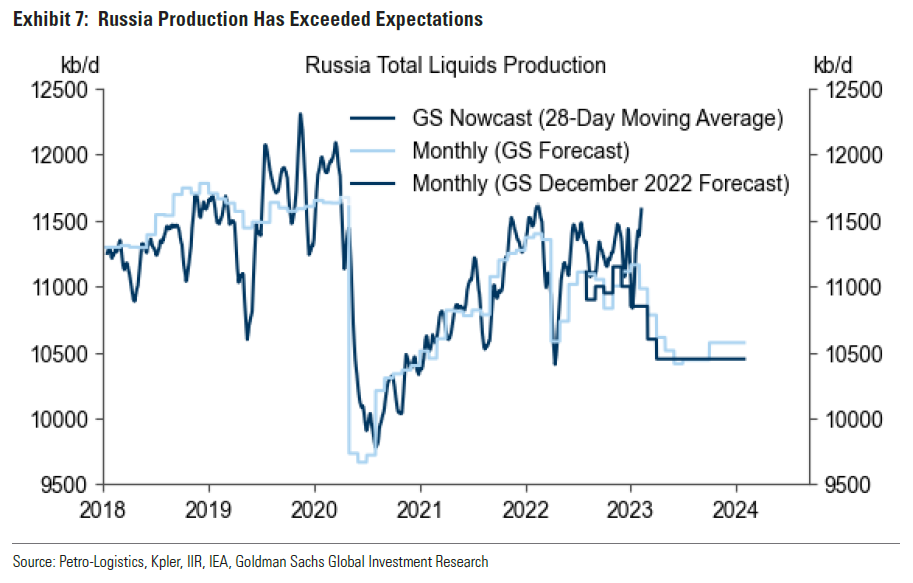

Moving onto Russia, surprisingly, Russia oil production has remained remarkably resilient since the beginning of the invasion into Ukraine. Sanctions on Russian oil did not manage to curtail Russian oil output as it was mostly diverted to Asia for refining before re-exported to the rest of the world. The fact is, we have not had to deal with a significant decline in Russian output yet, but this is about to change.

In February 23, Russia announced its plan to cut oil production/export by as many as 500K barrels per day. Ostensibly, the announcement was Russia’s response to the oil price cap under the sanction plan. It is also likely that the Russian government’s hand was forced as major Western oil services companies like Halliburton and Schlumberger withdrew from Russia and oil majors like BP and Shell exited their investments in Russia in 2022. It will be difficult for existing oil fields to be maintained properly without western equipment and expertise. The problem is made worse because some of the major oil and gas projects in Russia are in especially harsh external environment, such as the Artic LNG projects for instance.

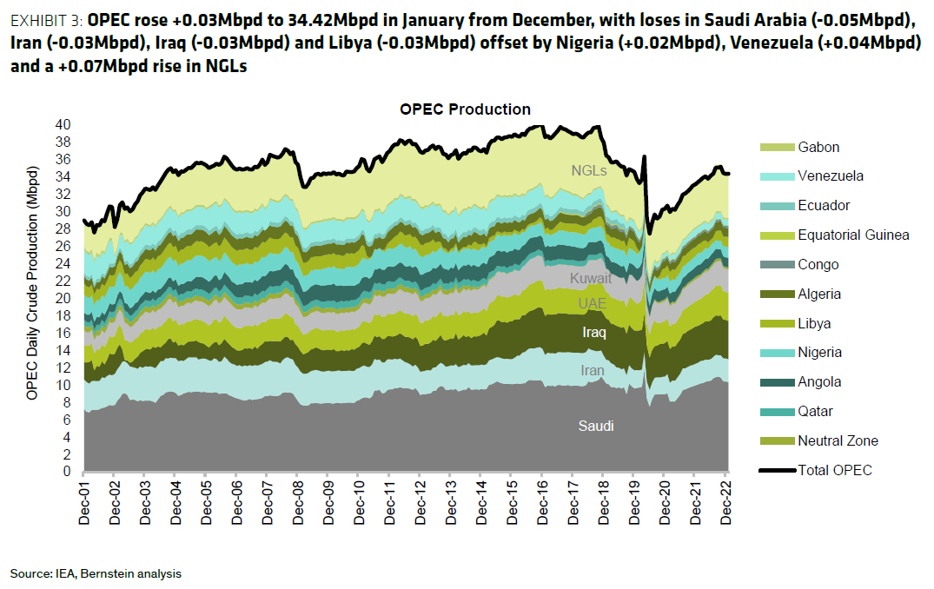

Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) is unlikely to be able to flex its supply significantly if energy market tightens. In the context of the general belief that OPEC can easily step into the void and cover any supply shortfall, it is striking to note that OPEC’s production appears to have peaked given the current level of capital investment.

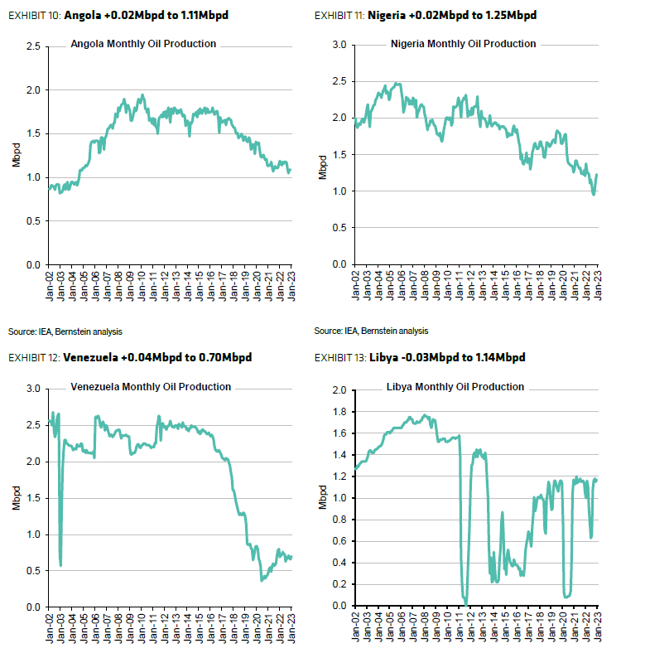

Within OPEC, Saudi Arabia remains a dependable source of supply, but it only contributes under one third of OPEC total production. The challenge within OPEC comes from its other member countries such as Iran, Kuwait, Nigeria, Angola, and Venezuela. These countries are producing far less oil (as much as 30-40% less) in 2022 than in 2017.

Furthermore, OPEC appears to have regained pricing power. OPEC in Oct 22 decided to unilaterally reduce oil production by 2M barrels per day when most global central banks and governments were fighting to tackle inflationary pressure. OPEC’s decision to act in its own interest at the expense of the rest of the world suggests a willingness to support oil price going forward when necessary.

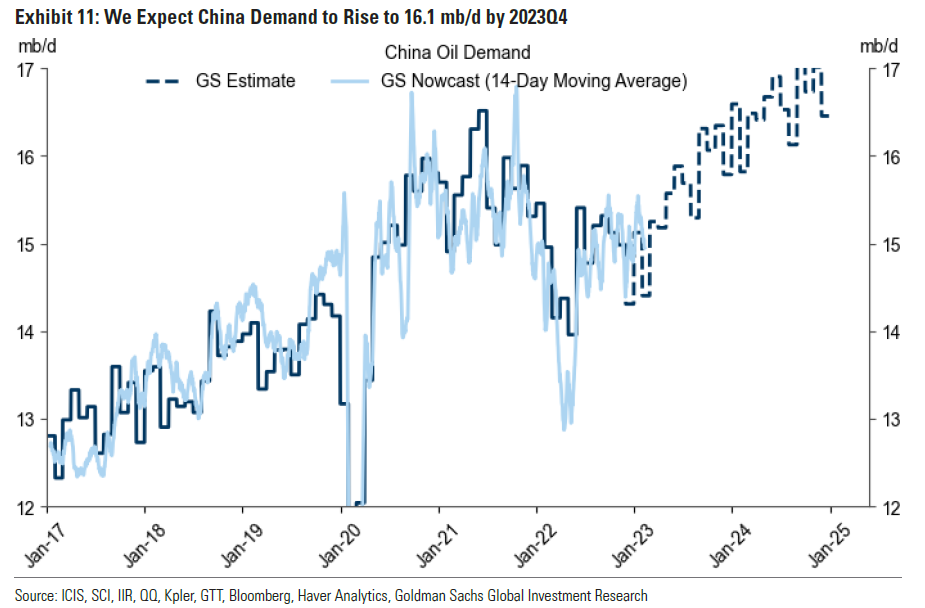

Shorter term, as global inventories are running at or below decade lows, and China’s reopening can drive a significant increase in demand as early as the second half of 2023.

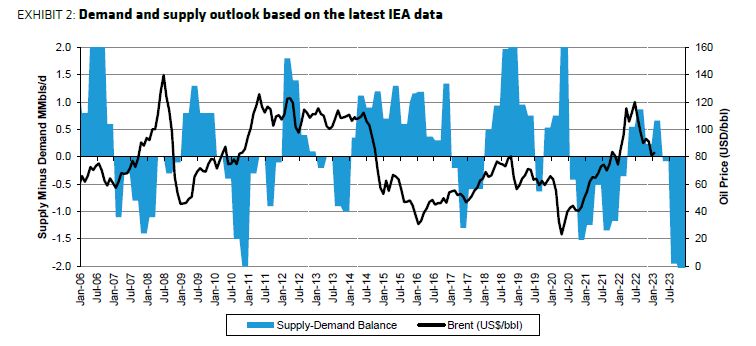

Demand may overtake supply in 2H 23, as suggested by forecasts from Morgan Stanley and Bernstein

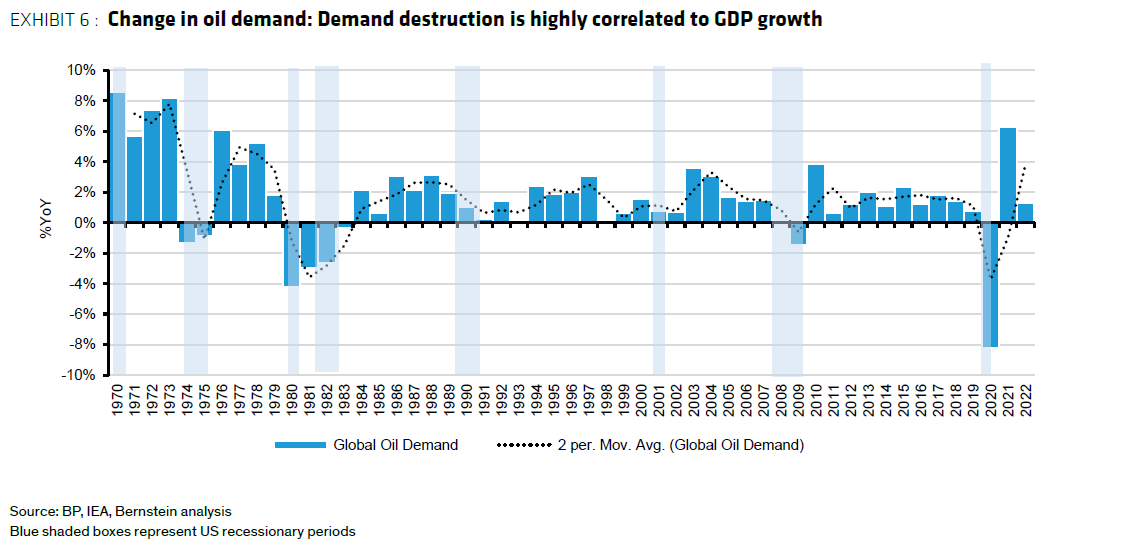

A risk to the positive energy case is the rising risk of a global recession. In a garden variety recession, physical demand has typically continued to grow. It is usually only in the extreme situation of demand destruction that oil demand fell a few percentage points. This included the oil price shock of 1979-82, the global financial crisis in 2008-2009 and during COVID where many parts of the world were in complete lockdown. While oil price can certainly fall if the global economy weakens, after years of sub-optimal return, just about all oil producers are rational these days and will react in their best interests.

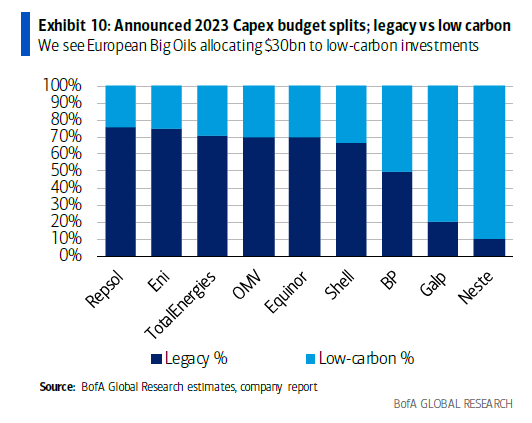

While we wait for the market to tighten, the oil majors are positioning themselves to navigate the energy transition responsibly. The European oil majors are investing typically greater than 30% of their capex budgets in low carbon initiatives.

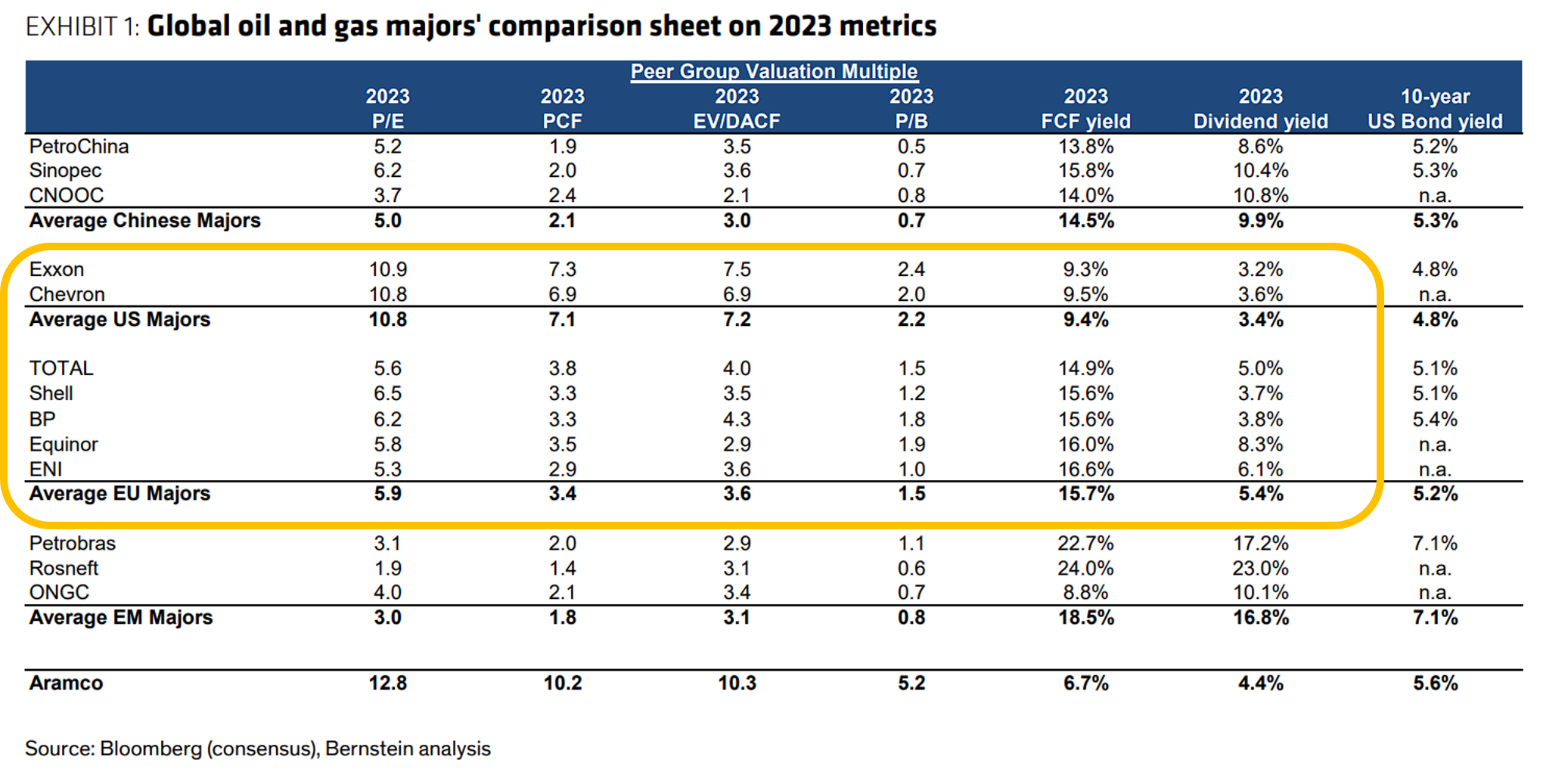

The EU majors are trading at significant discount to the majors in USA, they are more environmentally aware and are more exposed to the transitional fuel of natural gas. For instance, natural gas makes up 50% of Shell’s upstream revenue. For TotalEnergies, the proportion of gas in the upstream division is 40%. We believe they are more prospective.

The point we are making is that the global energy supply chain lacks resilience and demand is continuously increasing. The risk of a dramatic spike in energy price is not low. Investment in new greenfield projects has been constrained for some years, more and more capital needs to be invested in new fields just to offset decline in existing fields, and the Russian supply is just starting to decline. To the extent global economic slowdown can dampen energy prices, read the tea leaves, we believe OPEC’s preference is to support energy prices.

The stock market has not taken much interest in this sector and valuations are attractive. For instance, Shell is trading at 6X PE at an oil price of USD$80. If oil price drops to USD$60, it will be on 8X. Its dividend yield will be unaffected. It will still be able to deploy its FCF to buy back plenty of stocks.

At Ox, we buy quality leaders in an underappreciated theme when the valuation is attractive. The energy sector is one which we find highly prospective.

Take advantage of the rapid growth in Asia and emerging markets

Ox Capital's investment approach is to identify the immense changes taking place in Asia and other key emerging markets to find investment opportunities. To learn more, visit our website, or see the Fund Profile below.

1 fund mentioned

.jpg)

.jpg)