The cost of being too liquid

Legendary investor David Swensen famously stated that the “Intelligent acceptance of illiquidity, and a value orientation, constitutes a sensible, conservative approach to portfolio management”.1 What Swensen, and so many other sophisticated investors recognised, is the illiquidity premium available by allocating capital to illiquid investments like private equity, private credit, and private real estate.

In fact, throughout Swensen’s tenure as the chief investment officer of the Yale Endowment, he often allocated between 70-80% of his portfolio to alternative investments broadly, with illiquidity budgets of up to 50% of their total allocation. The illiquidity bucket is a technique used by institutions to identify the amount of capital that they are willing to tie-up for an extended period-of-time (7-10 years).

Of course, Endowments are very different than individual investors, and Yale has certain built-in advantages, including unique access to private markets, dedicated resources to evaluate opportunities, and long-time horizon. If Yale needs capital, they have the ability to reach-out to their well-heeled alumni and donors for additional capital.

Most high-net-worth investors would be uncomfortable locking-up so much capital – but the concept of an illiquidity bucket would certainly apply. While high net-worth investor may not have donors to call upon, they often do share something with Yale – a long time horizon for some of their goals.

What does the data show?

Academic research has shown the historic persistence of an illiquidity premium2– the excess return received for tying up capital for an extended period of time. This makes intuitive sense because you are providing the private fund manager ample time to source opportunities and unlock value. The fund manager isn’t beholden to investors and shareholders, like their public market equivalents, who are viewing results over shorter intervals.

While the magnitude of the illiquidity premium will vary over time, depending upon the market environment and the fund, the data shows that private equity, private credit, and private real estate has historically delivered a substantial illiquidity premium relative to their public market equivalents (see below).

Average 10-year Annual Returns of Private vs Public Markets

Source: Source: Franklin Templeton Capital Markets Insights Group; Private Debt = Cliffwater Direct Lending Index, US Bonds = Bloomberg US Agg Bond TR USD, Private Equity = US Burgiss Private Equity, US Equities = S&P 500 TR USD, Private Real Estate = NCREIF Fund ODCE Index, REITs = FTSE Nareit All Equity REITs TR USD.

Up until recently, high-net-worth investors had limited access to these elusive investments due to investor eligibility and high minimums. However, due to product innovation, and a willingness of institutional-quality managers to bring products to the wealth management marketplace, HNW investors now have a growing array of options to select from.

How much should advisers allocate to illiquid investments?

The amount of capital to allocate to illiquid investments varies by investors and their underlying liquidity profile. Many investors believe that they should be 100% liquid – but there is an opportunity cost, especially in today’s market environment. Traditional liquid market investments will likely deliver returns below their historical averages, and advisers may need to consider private markets to help investors achieve their goals.

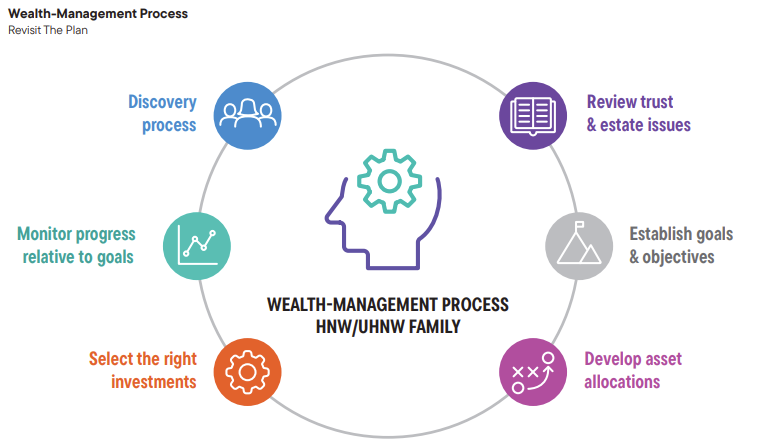

One way of determining the appropriate percentage to allocate to private markets is to develop an illiquidity bucket. Similar to the Yale example covered earlier, the illiquidity bucket should represent the amount of capital that an investor is willing and able to tie up for 7-10 years. It can be determined via the discovery process and advisers should designate these investments as long-term in nature.

As the adviser is determining the family’s needs and requirements, they should inquire about their short and long-term liquidity needs. Do they have significant capital expenditures in the next couple of years (college funding, purchasing a second home, boats, etc.)? How much of their portfolio needs to be short-term in nature to meet these needs? What portion are they comfortable putting aside for the next 7-10 years?

For many HNW investors, a 10-20% illiquidity bucket may be appropriate given their wealth, income, and cash flow needs. Once the adviser has determined the illiquidity bucket, they can then define which asset classes are appropriate to achieve their goals.

Allocating to private markets

Once the illiquidity bucket has been established for a particular client, you can then determine the appropriate allocation to private markets. There are several factors to consider before allocating.

- What are the family’s goals and objectives?

- What is the optimal combination of asset classes (traditional & alternatives)?

- What are the types of investments that provide the highest likelihood of achieving goals?

- What is the most appropriate type of fund given the investor’s wealth and liquidity profile?

- What is the appropriate amount of capital to allocate per strategy?

As with any investment, advisers must understand and evaluate the many dimensions of a fund before recommending (structure and strategy). Because of the specialised nature of conducting due diligence on private markets, advisers may rely on due diligence conducted by their firm or a third-party provider.

Conclusion

The bottom line is there is a potential illiquidity premium for allocating capital to private markets. The illiquidity premium is the reward for giving the fund manager ample time to execute their strategy and unlock value. There is an opportunity cost for being too liquid, especially in today’s market environment.

Advisers should help investors in determining their illiquidity bucket. The illiquidity bucket should be determined based on each investor’s ability to allocate capital for an extended period of time (7-10 years). An illiquidity bucket can help instill a long-term disciplined approach that can remove the impulses to respond to emotional stimuli.

Learn more

For further insights from the Franklin Templeton Institute, please visit our website.

Endnotes

(1) Source: David F. Swensen, Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment, Fully Revised and Updated

(2) Source: The Illiquidity Premium and the Market for Private Assets | Portfolio for the Future | CAIA