The great disconnect

BMO

We concluded our March quarter note with the comment: “Let’s just hope we now don’t have a gigantic bounce in share prices fuelled by the central bank injections, pushing them back to bubble levels. Or, are we, once again, being naïve?” Yes, we were being naïve. The bounce occurred and it had nothing to do with investment fundamentals.

The ‘money’ created by central banks is not connected in any way to income producing economic activity. It is generated by computer keystrokes. The modus-operandi is simple: Governments issue bonds to the market, the central bank manufactures its ‘money’ and buys them (or at least some of them) and when repayment of principal is required the government issues more bonds which are again purchased by the central bank and the fresh money is used to pay back the principal of the original issue. If this sounds like a giant Ponzi scheme you would be correct.

Some now advocate that the government simply issue the bonds straight to the central bank. In other words, join central banks and governments at the hip and keep the messy market out of the picture. This form of financing allows governments to spend without limitation as the bonds will never enter the private market. However, control over monetary policy is lost. Inflation targeting? Forget it.

Now whilst this somewhat esoteric economic debate may be fascinating to us we appreciate it will bore the socks off most of our readers so perhaps we should leave it there (for now) and take a look at what has been happening in the “real” world.

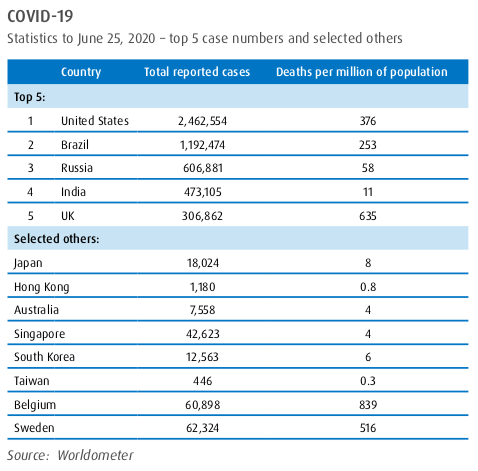

COVID-19 has created a huge economic crater. The climb-out will be much tougher and more protracted than many acknowledge as the world economy wasn’t in great shape when it entered the crisis – and, not to forget, the virus is yet to be defeated. What we find interesting is that deaths directly caused by COVID-19 are relatively few in number if measured per million of population. Many countries have done an outstanding job of containing the virus. Taiwan, for example, has recorded just 7 deaths which represents a rate of 0.00003% of the total population. Hong Kong with 6 deaths has a rate of 0.00008% and Australia with 104 deaths a rate of 0.0004%. Remarkable – especially when you consider that the annual flu season typically causes more deaths. The country with the highest recorded deaths relative to the total population is Belgium but even there the rate is 0.084%. The notorious Spanish flu which took hold at the end of the first World War allegedly killed an astonishing 50 million people or around 2.8% of the world population at the time (approximately 1.8 billion).

Has the lockdown been an example of government overreach?

Ultimately it is only the perspective of history that will be able to satisfactorily answer that question. There is much we still don’t know about the virus. And, of course, there may yet be a second-wave.

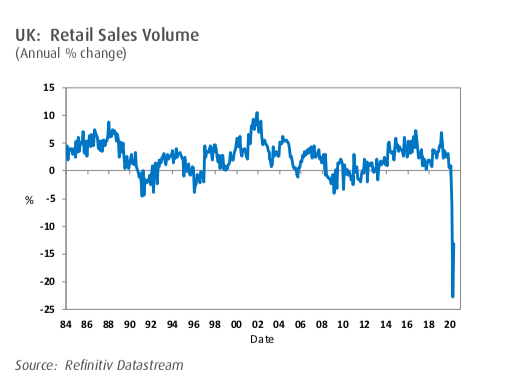

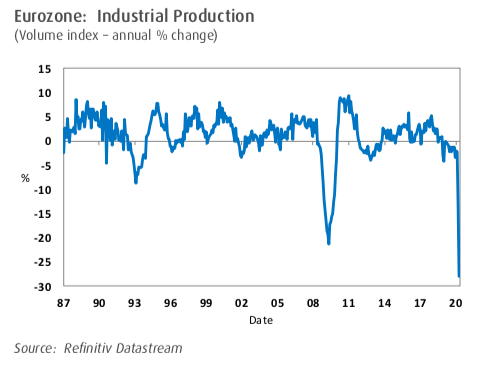

In our many years of scrutinising graphs and data relating to global economic activity we have never seen anything remotely like the data coming out of the last few months. We provide a selection over the next few paragraphs. If you weren’t aware of the economic cataclysm caused by COVID-19 you soon will be.

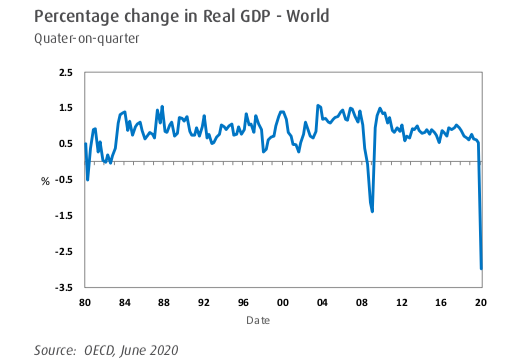

The OECD has released some timely data relating to the world economy. The quarter-on-quarter real GDP progression for the world is shown below. Clearly, the 2008-9 economic downturn (the notorious GFC) wasn’t a patch on this one. The June quarter result will also be miserable as April and May bore the brunt of the world-wide lock- downs.

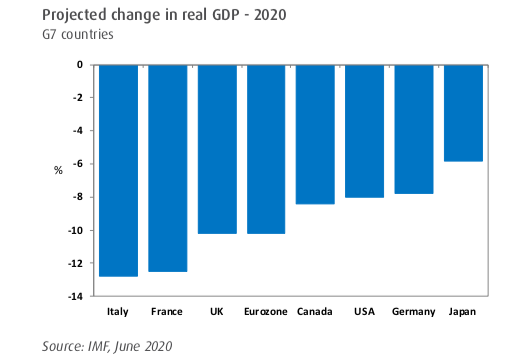

The projected change in real GDP in the world’s leading economies in calendar 2020 presents a picture that was unthinkable just a few months ago. When you shut most things down output has only one direction to go.

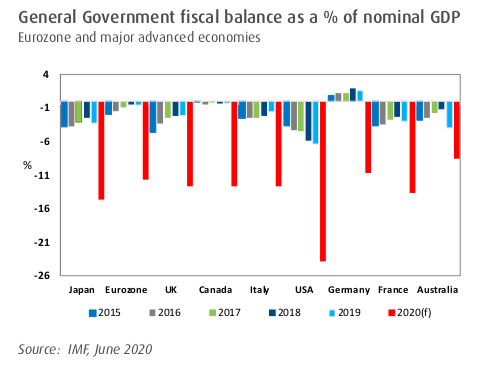

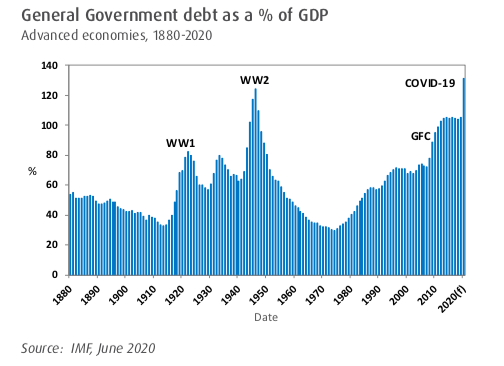

With governments throwing staggering sums of money at the ‘problem’ fiscal deficits attain dimensions that are without precedence. Some countries have fiscal space because overall government debt levels are relatively modest (Germany and Australia are examples), but most countries are not in this favourable position. Without wishing to burden you with too many graphs we can advise that Japanese Government gross debt will climb to around 268% of GDP as a consequence of the massive fiscal spend whilst those tracking at more than 100% of GDP include: USA (141%); Italy (166%); Spain (124%); France (126%); UK (102%) and Canada (109%). Germany and Australia come in at 77% and 57% respectively. (IMF projections for general government gross debt balances relative to GDP at the end of 2020).

If we examine the aggregate government debt levels in the advanced economies based on a long-term perspective, we can now see that COVID-19 has taken them over the peak level attained during the second World War. It has been said that fighting the virus is akin to fighting a war and that analogy now appears particularly apt.

The difference this time is that the government debt to GDP ratio fell rapidly after WW2 because of post-war reconstruction and a high birth rate which introduced many young and willing workers into the workforce over the ensuing decades. GDP bounded ahead at a much faster pace than debt accumulation – a pattern that ceased in the 1980s.

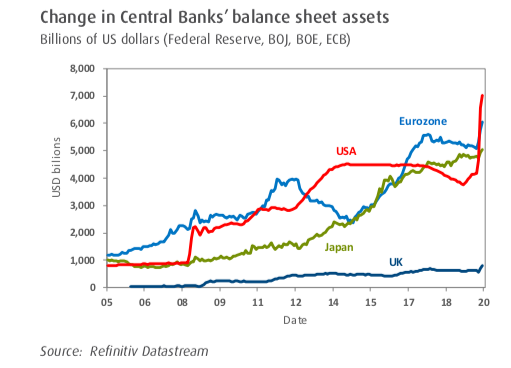

The Bank of Japan has been buying equities for years through ETFs whilst the Swiss central bank has been doing the same – only in their case through direct stock purchases in the market. Apparently, Apple is one of their largest holdings. In the US, apart from Treasuries, the Fed has long been buying Municipal bonds, mortgage-backed securities and other bits and pieces. It has now announced, however, that it will be buying corporate bonds. This is a first. The US corporate sector has more debt relative to income than at any time in its history and a good percentage of it is sliding down the credit rating scale. Around half is at the lowest investment grade (BBB) - just one step from ‘junk’ and perilously close to slipping into that category. It is mainly these bonds that the Fed will be buying. The Fed is also prepared to purchase bonds direct from corporations and participate in issues of syndicated loans. With intervention at this level any semblance of the market mechanism has been washed away.

In October last year the balance sheet of the Federal Reserve was less than $4 trillion. Today, it is over $7 trillion – equivalent to around a third of US GDP. The Fed has no plans to stop buying. It certainly has no plans to increase interest rates. In the memorable words of the Chairman of the Fed it is “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates.” The other key central banks in the world are also piling on the dollars although the rate and scale of expansion by the Fed dwarfs them. The IMF has calculated that as of mid-May the COVID- induced additional monetary deployment (expanded budget deficits, loans, equity injections, guarantees and various other quasi-fiscal operations) amounted to a staggering $9 trillion in the G20 economies. It will not stop at that figure.

The impact of the lockdown has varied by industry, but the most adverse impact has been in the areas of accommodation and food services, arts, entertainment, and recreation. The OECD estimates that shutdowns in these industries averaged 70— 80% across most countries.

Retail sales statistics have racked up record falls everywhere. Typical is the collapse in the UK:

In the eurozone industrial production has dived by almost 30%. It didn’t even manage that sort of fall in the GFC. Exports are down a similar percentage.

The most vulnerable eurozone economies remain those with high public debt levels and anaemic growth. The IMF estimates that by the end of 2020 gross government debt relative to GDP will amount to 200% in Greece, 166% in Italy and 135% in Portugal. None can ‘print’ as those tools were given away when the common-currency bloc was formed. Interest rate policy and the printing presses remain in the hands of the ECB. They cannot depreciate their currencies and they are fiscally constrained because of eurozone policies. Both Italy and Greece will end 2020 with real GDP no higher than the level prevailing 20 years ago whilst Portugal will be only marginally ahead. The OECD estimates that Italy’s real GDP will fall 11.3% this year, Portugal’s 9.4%, and Greece’s 8% (assuming no second-wave of the virus). Either the rule book is thrown out and eurozone-wide debt pooling is formally adopted along with fiscal integration or selective exits from the ‘zone’ must be contemplated. The grand experiment which began in 1999 cannot in any sense be called a success. COVID-19 will either hasten its demise or result in significant reconstruction.

Hong Kong finds itself in a pickle. The suffocating Beijing blanket is descending despite the ‘one country, two systems’ policy that was, in theory, in place for 50 years post-handover to the communist power in 1997. We have no idea where this is heading, no one does, but it cannot be a good sign that the rules appear to be changing less than half-way through the 50 years.

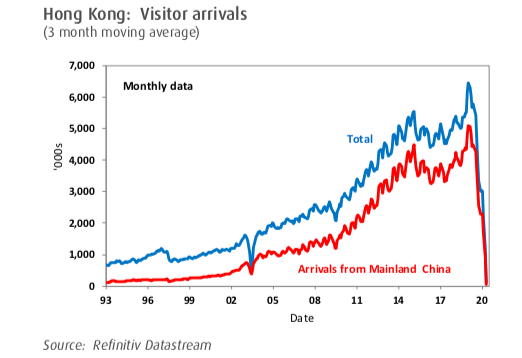

In the meantime, the Hong Kong economy has imploded. GDP was already tumbling in the final two quarters of 2019 but then a nosedive occurred in the first quarter of 2020 (down 9% on a year earlier). The second quarter of this year will see it fall further. Retail sales are down over 40% (year-on-year) but one of the most startling statistics is the number of visitor arrivals.

Prior to COVID-19 there were almost 7 million a month. Today, the numbers are down to a trickle. There is, however, a benefit- Hong Kong has been virtually virus free but for an economy that relies so heavily on tourism and trade it is a hefty price to pay.

Hong Kong has always been a favoured destination for expatriates. It provided a combination of very low taxes and an exciting, vibrant commercial and financial hub where careers could quickly advance. The property market boomed on the back of the ex-pat community and the massive inflow of people and cash from China (which accelerated after the 1997 handover). The consequence is that Hong Kong has the most expensive real estate market relative to median incomes in the world – or, at least, it did. Quite where it is now is hard to say. It seems that a good number of ex-pats are waving goodbye to their Hong Kong sojourn whilst the dramatic drop in visitor arrivals will also be biting on property prices. Back in the ‘old days’ Hong Kong property was always a boom and bust market. Perhaps it will now revert to type.

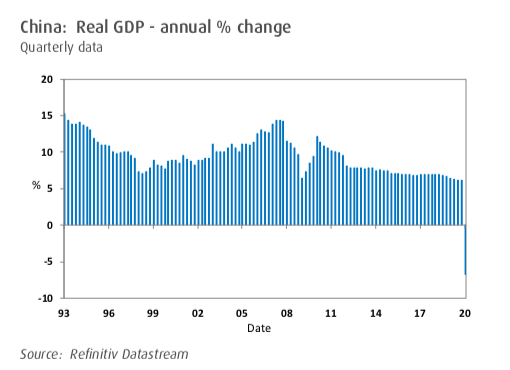

In China real GDP has suffered its first year-on-year fall in decades – down 6.8%. We get so used to the carefully managed upward trend that it is a shock to see a sizeable negative number. Retail sales fell by 19% and investment in fixed assets by 16% in the first quarter. China locked down before other countries and re-opened earlier than most so it is possible that the second quarter will see some pick-up but these are such unusual times that it is dangerous to make forecasts – particularly in relation to an economy where all data releases can be subject to ‘interpretation’.

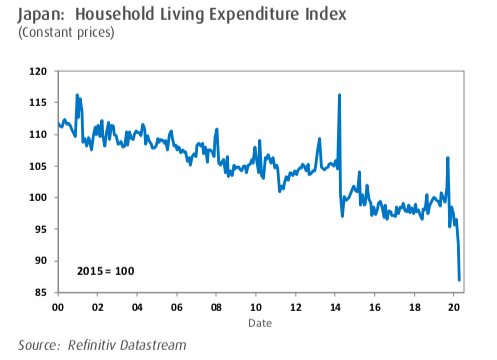

In Japan retail sales volumes have dived to a level significantly lower than 30 years ago whilst real household living expenditure has maintained a steady downward trajectory - but with a spectacular fall in the latest quarter. Real wages peaked in 1997. Since 2011 real labour productivity growth has averaged just 0.2%. Japan is suffering from a declining population so it will come as no surprise that retail sales are weak, but the erosion of real incomes is painful.

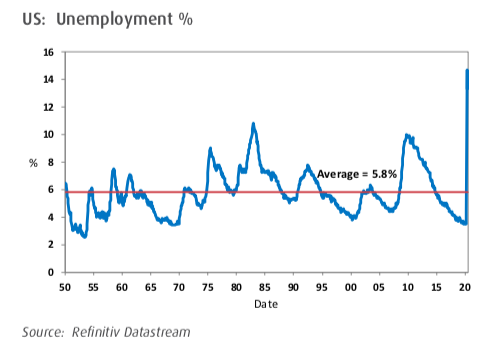

In the US, the most spectacular COVID chart relates to unemployment – zooming to 14% in a blink of an eye – and this springing from a level that was getting close to equalling a 70-year low. As the various States sporadically and unevenly reopen there will be a bounce back from this shocking number but in common with many other countries there will be some who will choose to accept the variety of government hand-outs in preference to re-entering the workforce.

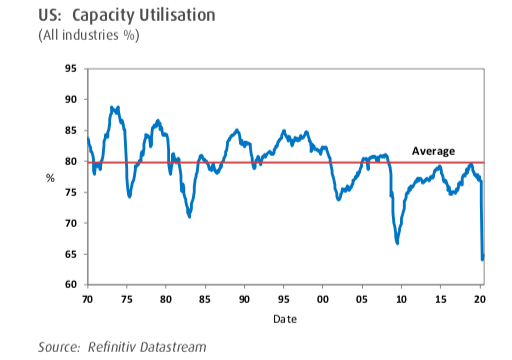

Another disturbing US chart demonstrates the pronounced slide in industry capacity utilisation since the beginning of the pandemic. It is now at the lowest level for 50 years.

On average, US industry will now be seriously unprofitable. In the first quarter whole-economy pre-tax profits fell by 14% to take them back to the level last prevailing in the third quarter of 2011. Even before this tumble pre-tax profits had been flat for six years – not something that was obvious from stock market moves or the President’s Tweets. In the second quarter we can expect further dire profit reports. Whether the plunge from peak to trough will equal the 2008 wipe-out - a fall of 40% from 2006 – is something that is impossible to forecast as the extent and pace of global re-opening is still uncertain.

In its recent Economic Outlook the OECD commented on a survey of almost 1 million firms across Europe and discovered that without any policy intervention 20% of the firms would run out of liquidity after one month, 30% after two months and 38% after three months. If the confinement measures lasted seven months, more than 50% of firms would face a shortfall of cash. Most of the firms are profitable and viable companies... “however, a sizeable share of these firms do not have enough collateral to bridge a shortfall in liquidity with additional debt and/or are too highly leveraged to bridge the crisis through further bank loans.”

In its economic overview the OECD states that in a “typical” OECD economy, even assuming some recovery in 2021, real per capita income will only get back to the level prevailing in 2016. If there is a virus second-wave real per capita income will fall to the 2013 level. In other words, the world is facing a decline in income equivalent to at least five years growth. Possibly a lot more.

Translation: this is serious.

The final word

There is no doubt that the financial world marches to its own drumbeat. If you are employed in this world COVID-19 has probably been little more than a minor inconvenience. If you work for an airline, restaurant, hotel chain or an abundance of the other ‘early-hit’ industries COVID-19 has been a catastrophe.

As we see it the problem is that growth was only creeping along prior to COVID-19. Much of the world economy has remained on life support since the GFC – absurdly low interest rates, ongoing infusions by central banks (all of whom panic at the slightest step-back by markets) and steadily increasing government debt levels. Any reduction in overall debt by consumers has been more than made up for by corporates and governments. Consequently, the global debt to GDP ratio entered the COVID crisis at a record level.

The pricing and allocation of risk becomes seriously distorted when central banks splash the cash. Scarce resources are misallocated. Stock markets turn into a one-way trade. Zombie companies continue to walk the earth.

Productivity growth, virtually everywhere, has been abysmal. Why? The simple answer is that capital investment has been running at low levels relative to the past. Again, why? We put it down to increasing short-termism in the corporate world – the pursuit of quick rewards combined with general nervousness about the future.

Non-existent (or negative) interest rates and bloated central bank balance sheets don’t inspire confidence.

The only way to get out of the crater is to foster sensible long- term capital investment. The economy has to return to a situation where growth exceeds (or at least equals) private and public debt accumulation. It is almost 40 years since this last occurred. Sadly, we have little confidence that this will happen in the foreseeable future as the world enjoys the central bank ‘fix’ and government largesse.

When the COVID crisis eases governments and central banks have to get out of the way of the economy – there is no option.

Many years ago, Ronald Reagan uttered the following insightful comment about the government’s view of the economy: “If it moves, tax it. If it keeps moving, regulate it. And if it stops moving, subsidise it.” The world is clearly enmeshed in all three but with increasing emphasis on the latter.

Access a global multi-asset investment strategy

Pyrford seeks to provide a stable stream of real returns over the long term with low absolute volatility and significant downside protection. To find out more, click the 'CONTACT' button below.

Tony joined Pyrford in 1989 and headed its European and UK investment management activities before becoming Chief Executive and Chief Investment Officer in January 2011. Tony has a Masters of Arts degree and is a CFA.

Expertise

Tony joined Pyrford in 1989 and headed its European and UK investment management activities before becoming Chief Executive and Chief Investment Officer in January 2011. Tony has a Masters of Arts degree and is a CFA.