This investment theme is broken, with US$34 trillion on the line

Sustainable investing is here to stay, as institutions and private investors alike demand firms be greener, more accountable and more equitable.

From its origins as a footnoted afterthought, ESG (environmental, social, and corporate governance) focused investing is now projected to account for US$33.9 trillion dollars (21.5%) of funds under management in 2026.

But, absent the efficient and productive allocation of these resources, the movement's lofty aims will fall short of the mark.

Striking new research co-authored by Samuel Hartzmark from Boston College and Kelly Shue from Yale has found that the current sustainable investment regime is counterproductive. So counterproductive, in fact, that it's making firms perceived to be “brown” (negative environmental impact) even more brown, at the expense of making "green" (positive environmental impact) firms more green.

This wire will summarise that research.

And just to be clear, this wire is about the impact of the ESG movement from an investment standpoint. Those hoping it will out ESG as a scam, or are wanting to argue the validity of climate change, should jog on and yell at each other in another room.

As the authors note themselves, "Our findings and conclusions are not meant as a negative assessment of all possible sustainable investment strategies. Rather, they highlight potential problems with the most popular sustainable investment strategy to date."

The dominant strategy

As it relates to emissions, firms can be broadly split into three categories.

Brown firms have the worst ESG metrics. Green firms are at the other end of the spectrum with the best ESG metrics. Then there's everything else in between.

For the sake of argument, the research focuses on green and brown firms - i.e. those firms that represent the top 20% and bottom 20% of the distribution.

The paper offers a great hypothetical analogy describing the practical differences between the two:

Travelers is an insurance firm in the S&P 500 that looks spectacular on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics. Travelers widely advertises its low greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, it emitted 33,477 metric tons of carbon, which is about 1 ton per million dollars of revenue. At the opposite extreme lies Martin Marietta Materials, another S&P 500 firm that supplies heavy building materials. Amongst ESG ratings providers, Martin Marietta is uniformly considered poor. In 2021, it emitted about 5.1 million tons of carbon, corresponding to about 1,000 tons per million dollars of revenue. Relative to Travelers, Martin Marietta has 1000 times as much emissions intensity, measured as emissions scaled by revenue."

(Take note of this case study, as I'll refer back to it later in the piece.)

The prevailing ESG strategy prioritises investment in companies perceived to be green in place of companies perceived to be brown. Thus, "it rewards green firms by lowering their cost of capital and punishes brown firms by raising their cost of capital."

In the above case study, investment capital flows to Travelers because of its minimal carbon footprint. By extension, capital is directed away from Martin Marietta because of its large carbon footprint.

Why it's broken

At its crux, the research found that directing capital to green firms over brown firms makes the brown firms browner without making green firms any more green.

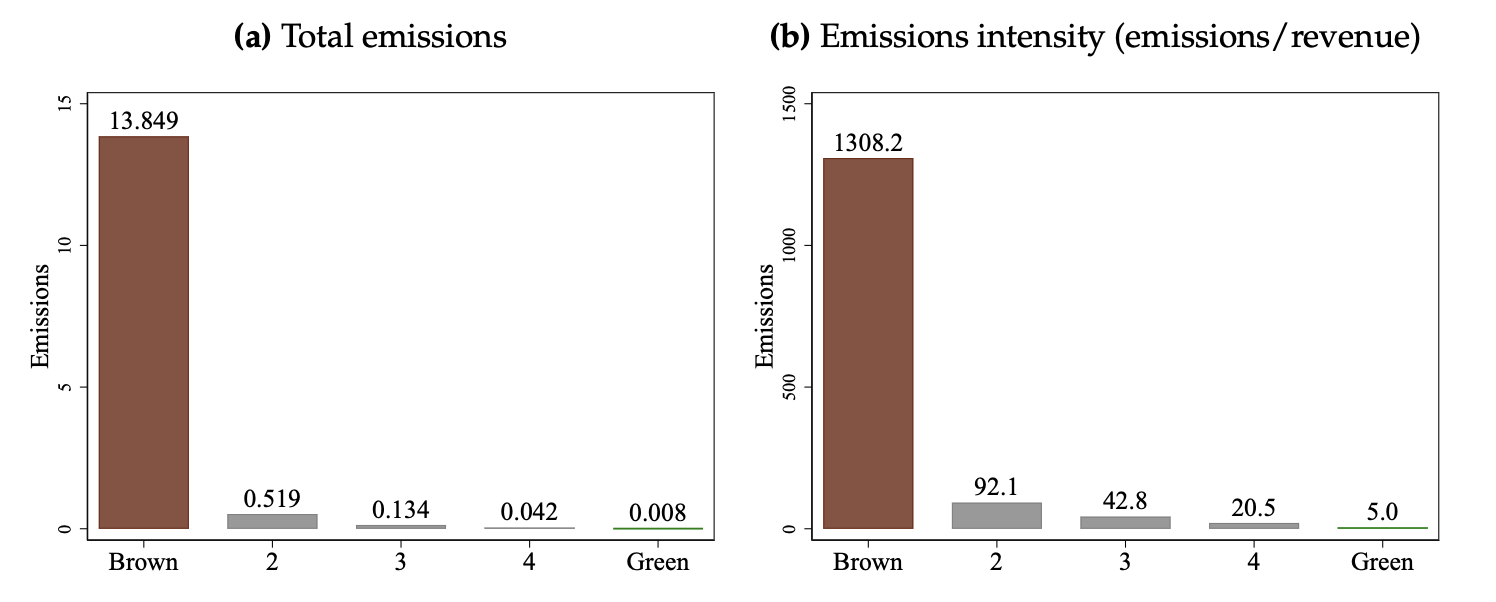

Marry that with the finding that (all things being equal) brown firms have approximately 260 times as much environmental impact as similarly-sized green firms, and you see how big the problem is.

This figure plots the average emissions of scope 1 and scope 2 greenhouse gases by firms, sorted into quintiles within each year, with quintile 1 representing brown firms and quintile 5 representing green firms. In Panel (a), emissions are measured as million tons of CO2 equivalents. In Panel (b), emissions are measured as tons of CO2 equivalents emitted per million dollars of revenue.

A reduction in financing costs for firms that are already green leads to small improvements in impact

Much of the distribution problem centres around the tendency for investors to prioritise emissions reductions in percentage rather than absolute terms.

"Sustainable investors appear to suffer from a proportional thinking bias in which they reward firms with large percentage reductions in emissions rather than large level reductions in emissions. Influential ESG environmental ratings similarly reward percentage reductions in emissions rather than level reductions in emissions."

What's more, brown firms and green firms have drastically different emission profiles to begin with. So a high percentage reduction in emissions by green firms can lead to a low reduction in overall emissions, whereas a low percentage reduction among brown firms will result in a far greater improvement in overall emissions.

"Due to a mistaken focus on percentage changes in emissions, the sustainable investing movement primarily rewards green firms for economically trivial reductions in their already low levels of emissions."

"A 100% reduction in emissions by a green firm is far less economically meaningful than a similarly-sized brown firm reducing its emissions by a mere 1%."

By the same token, the focus on percentage change provides brown firms such as Martin Marietta with little incentive to reduce their emissions.

Increasing financing costs for brown firms leads to large negative changes in firm impact

The research developed a measure called "impact elasticity", defined as "a firm’s change in environmental impact due to a change in its cost of capital."

It found that brown firms (especially highly levered ones) typically respond to financial distress or the increased cost of capital by raising emissions.

Going green is good for cashflows in the long term but bad in the short term. So during periods of financial distress and increased cost of capital, brown firms naturally prioritise short-term cashflow.

"Brown firms likely face a choice between dark-brown investment projects (e.g., continuing or expanding existing high-pollution operations, or cutting corners on pollution abatement) and light-brown investments (e.g., shifting toward cleaner production or green energy). Because the light-brown investment project entails a departure from existing production methods, it likely requires investment in new capital which costs more up front and delivers back-loaded cash flows compared to the dark brown project."

And given that brown firms are higher emitters to begin with, increased cost of capital has an outsized impact on overall emissions.

"In contrast, a green firm likely operates in a line of business (e.g., insurance in the case of Travelers) where the firm cannot generate substantial environmental externalities regardless of which investment projects it chooses to pursue, leading green firms to have impact elasticities close to zero."

"Green firms exhibit low variability in impact and close-to-zero impact elasticity with respect to changes in their cost of capital. In contrast, brown firms have approximately 260 times as much environment impact as similarly-sized green firms, and have substantially greater scope for change. Brown firms exhibit large negative impact elasticities—they become substantially less brown in response to easier access to capital and more brown if pushed toward financial distress."

Where to next?

The actionable takeaway from the research is clear - investment dollars in brown companies go much further than the same dollars invested in green companies.

To use the case study provided, the most sustainable investing strategy dictates that investors should invest in Martin Marietta rather than Travelers.

"If money flows toward Travelers allowing further investments in green projects at subsidized rates, where would it go? If Travelers were able to cut emissions by 100%, it would be equivalent to Martin Marietta cutting its emissions by a mere 0.1%. As an insurance firm, Travelers is also very unlikely to develop new green technology that could be adopted by other firms. On the other hand, Martin Marietta has the capability of becoming much more green or brown. While the company emits a large amount of carbon, it does so after having made significant green investments to cut its emissions per ton of cement from 0.84 in 2016 to 0.77 in 2019."

How do we get to this new regime?

Well, investment simply needs to be redirected towards the companies for whom change will make the most difference in absolute terms. And for that to happen, ESG investment needs to put greater emphasis on emission levels, not the percentages they represent within firms, and incentivise accordingly. Time for less feel-good green ticks and more heavy lifting.

Seems simple enough, but something tells me that getting there will be decidedly less so.

2 topics