Three weeks on, what did we learn from the banking crisis?

Completing our cycle of three webinars on volatility in the banking sector, Kim Catechis, Investment Strategist, Franklin Templeton Institute, gave his perspective on recent events, where we are now, and what the implications are for markets in Europe and globally.

Three weeks after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and two since UBS took over Credit Suisse, what have we learned?

The markets appear to have largely digested the events of the last three weeks, but investors are reminded of a few banking sector “home truths” that remain constant:

- Banking, like investment, is all about confidence.

While many understand that deposits are (mostly) guaranteed, it is hard for concerned customers not to withdraw cash during periods of market stress. This is why regulators in the United States acted fast and dealt with these concerns comprehensively. Another learning is that confidence in a bank is also built on its capital structure, as well as its capital adequacy. This episode emphasizes the need for trusted institutions and regulatory oversight, both of which international investors appreciate. That is a global phenomenon.

- Recent events might strengthen the arguments against looser regulations.

Until a month ago, there were strident voices in the United States and the United Kingdom demanding looser regulation, in the name of competition. However, in light of recent events, we should expect increased regulation and oversight globally. Some of those new regulations may have the effect of slowing economic growth, and raising the cost of funding for banks and the cost of doing business for entrepreneurs. For those whose deposits were made whole, this may be viewed as a price worth paying.

- Marketable securities will have to be considered riskier than we had thought.

Liquidity in accounting terms comes in many varieties, some of which are not cash at all. While depositors don’t usually consider the balance sheet strength of the bank they choose, from an investor’s standpoint, it appears that this is exactly the sort of depth of due diligence that is required to avoid surprises. When interest rates are rising, US Treasury bills may be safer than equities, but they do not keep pace with future interest rate increases. This mismatch can erode bank liquidity, as it did with SVB.

And now for some charts:

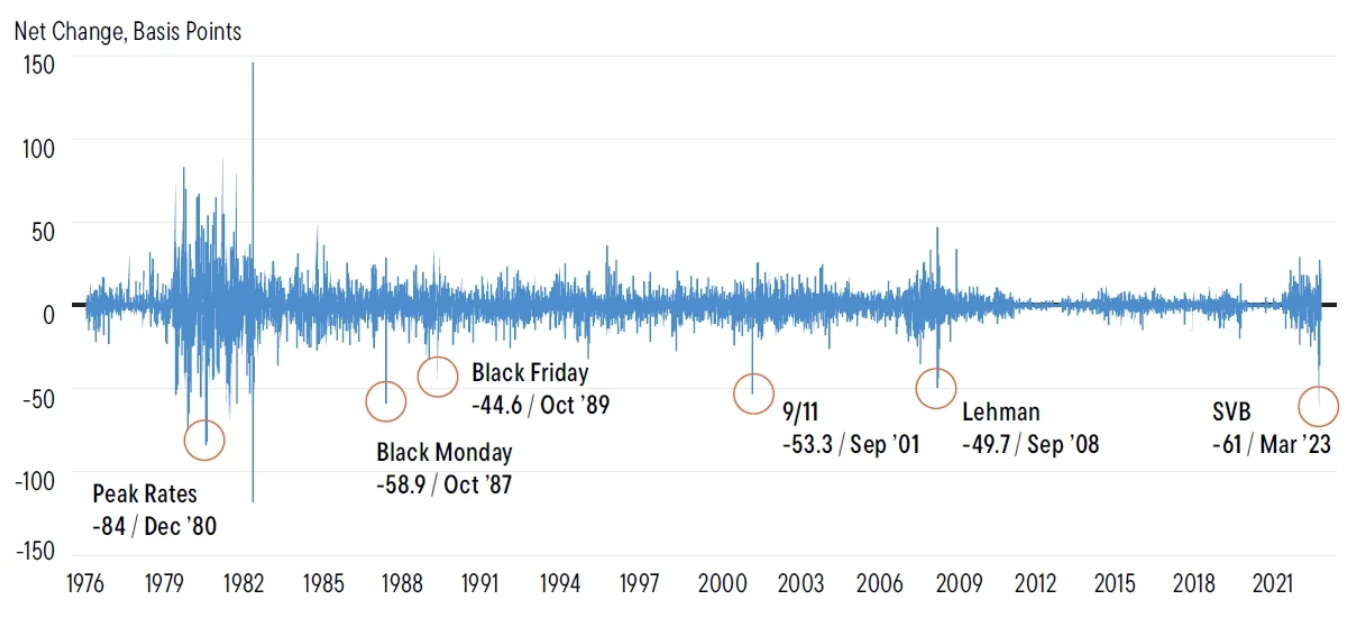

Exhibit 1: Seven Sigma Move on the Front End of the Yield Curve

US Short-Term Yields Fall Most Since the 1980s Two-Year Treasury Rates Fell Over 60 Basis Points on Monday, March 13

Sources: Bloomberg, Macrobond. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future results. See (VIEW LINK) for additional data provider information.

Over the last few weeks, sharp moves at the front end of the yield curve led to a significant plunge in Treasury yields. The market clearly thought that there was a problem with the short-term rates and expected the Federal Reserve (Fed) to ease monetary policy soon. We experienced a seven-standard-deviation move on the front end of the yield curve for the first time since 1987 as two-year yields dropped 60 basis points (bps). On March 8, SVB announced it would book a US$1.8 billion loss after selling some of its investments to cover increasing withdrawals; within 48 hours California state regulators and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation had intervened. The biggest drop in the two-year US Treasury yield was on March 13, as investors got a chance to express their view that the Fed was wrong and should cut rates immediately.

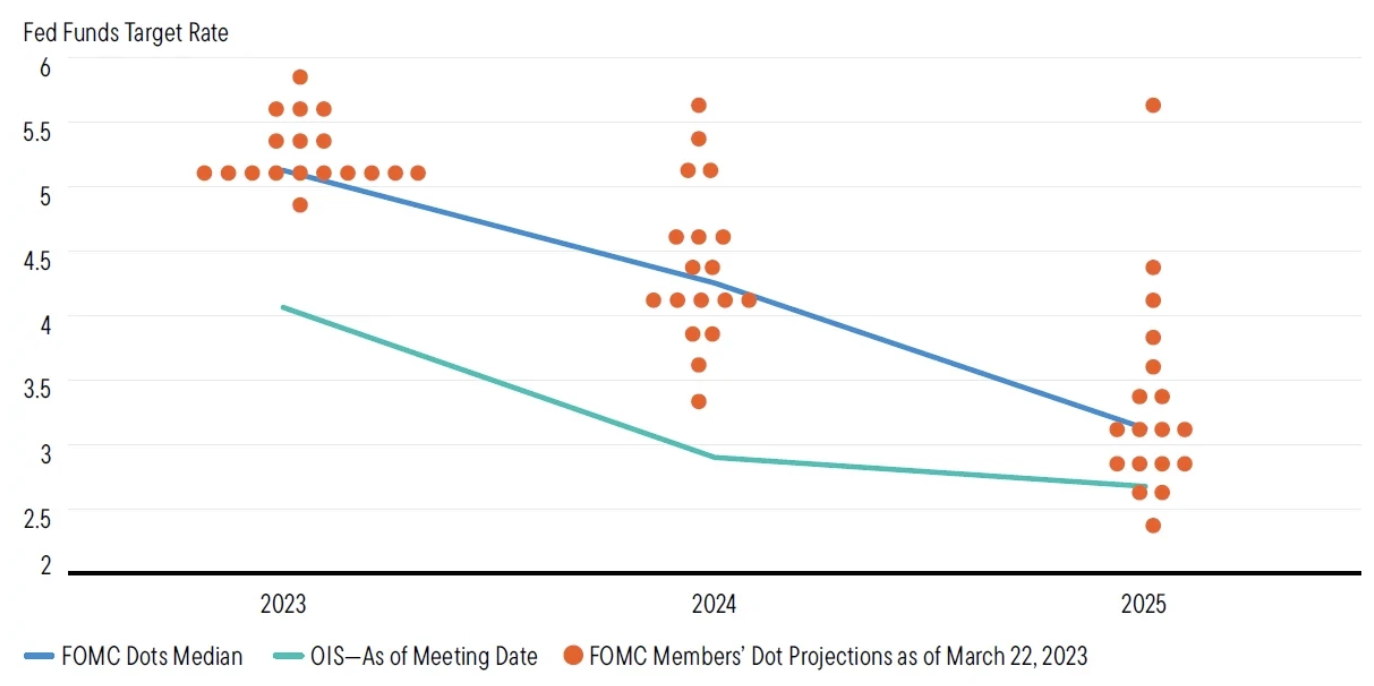

Exhibit 2: Tug of War Between the Fed and Markets

Sources: Bloomberg, US Federal Reserve. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.

Exhibit 2 is the famous “dot plot” chart, where each orange dot represents the view of a Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) member on the appropriate level for the fed funds rate. The median of these views is illustrated by the blue line.

The green line represents market expectations; these are based on the overnight index swaps (OIS) market.

The chart shows that the Fed and fixed income markets differ significantly in terms of their assessment of the right level for the terminal interest rate. The market has been consistently pricing a more dovish path for interest-rate hikes since the third quarter of 2021; however, the gap between the market and the FOMC projections has been increasing and it is now (as of FOMC meeting on March 22) over 100 bps. In other words, the FOMC members think that one more hike (25 bps) is appropriate in 2023, while the market believes the Fed target rates should drop by approximately 100 bps from where we are today. This divergence is important for investors, as expected returns are dependent on which of these two paths will eventually materialize. Of course, we all know that these expectations fluctuate daily, so please do not treat them as carved in stone!

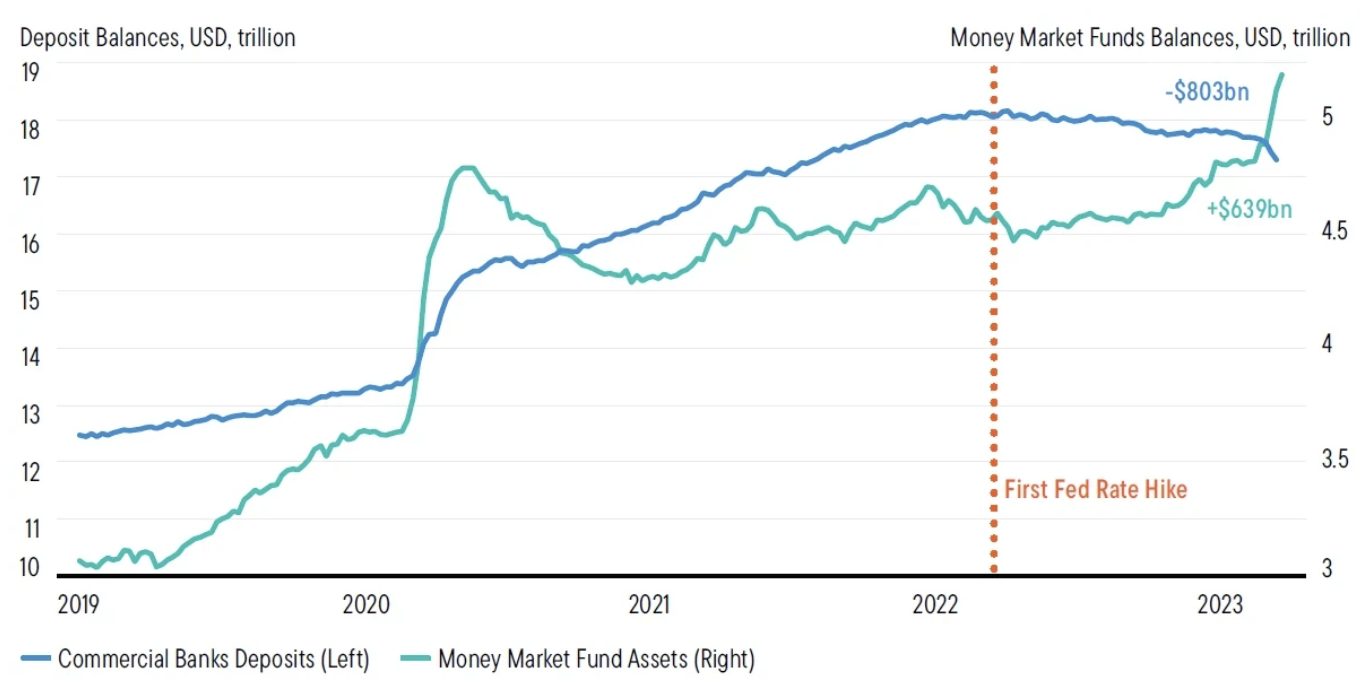

Exhibit 3: Money Markets In, Bank Deposits Out

US Money Market Funds vs. Bank Deposits

Sources: Federal Reserve, ICI, Macrobond, as of March 2023.

This chart shows the increasing switch out of bank deposits and into money market mutual funds. On one level, depositors are diversifying their accounts among commercial banks because they are looking for deposit guarantees, yet money market funds continue to attract inflows because of slightly higher yields. Deposit rates have broadly started to rise, but they remain below money market mutual fund yields, implying that outflows of bank deposits will probably continue. The 14% increase in money market fund balances (US$639 billion) since March 2022 (first Fed rate hike) compares with a 5% decline (US$803 billion) in US commercial bank deposits. [Deposit data trails money market fund figures by seven days.] This deposit flight may cause banks to either continue to raise rates to maintain deposit levels, or to restrict lending.

Exhibit 4: Treasuries Versus Equities

Sources: Bloomberg, Macrobond. European stocks are represented by the STOXX 600 Europe Index. US stocks are represented by the S&P 500 Index. European government yields are represented by 10-year bund yields. US government yields are represented by 10-year Treasury yields. Indexes are unmanaged and one cannot invest in them. They do not include fees, expenses and sales charges. Past performance is not an indicator or guarantee of future results. See (VIEW LINK) for additional data provider information.

Asset allocators often compare the relative attractions of bonds versus equities. The current spread between the earnings yield on the S&P 500 Index and the 10-year Treasury yield has contracted to around 161 bps. Investors consider this to be the risk premium, or the compensation investors get for the greater risk and volatility of equities over government bonds. This now stands at 1.6 standard deviations below the 10-year mean. The implication is that the case for stocks is weakened. Historical analysis suggests that investors typically take this as an attractive entry point for Treasuries.

In Europe, the story is less clear, as you can see from the right-hand side of Exhibit 4. The spread between equity earnings yield and the 10-year Bund yield is 495 bps, which means that it is 0.5 standard deviations below the mean over a 10-year period. The spread is somewhat lower; however, statistically speaking, we cannot say that it has reached extreme territory, which means that the signals for asset allocators are inconclusive.

Never miss an insight

Stay up to date with all my latest insights by hitting the follow button below, or visit our website for more information.

As Franklin Templeton’s Chief Market Strategist and Head of the Franklin Templeton Institute Stephen Dover leverages the knowledge of the firm’s autonomous investment teams to provide global capital market and long-term investment insights...

Expertise

As Franklin Templeton’s Chief Market Strategist and Head of the Franklin Templeton Institute Stephen Dover leverages the knowledge of the firm’s autonomous investment teams to provide global capital market and long-term investment insights...