The ramifications of QE in Australia

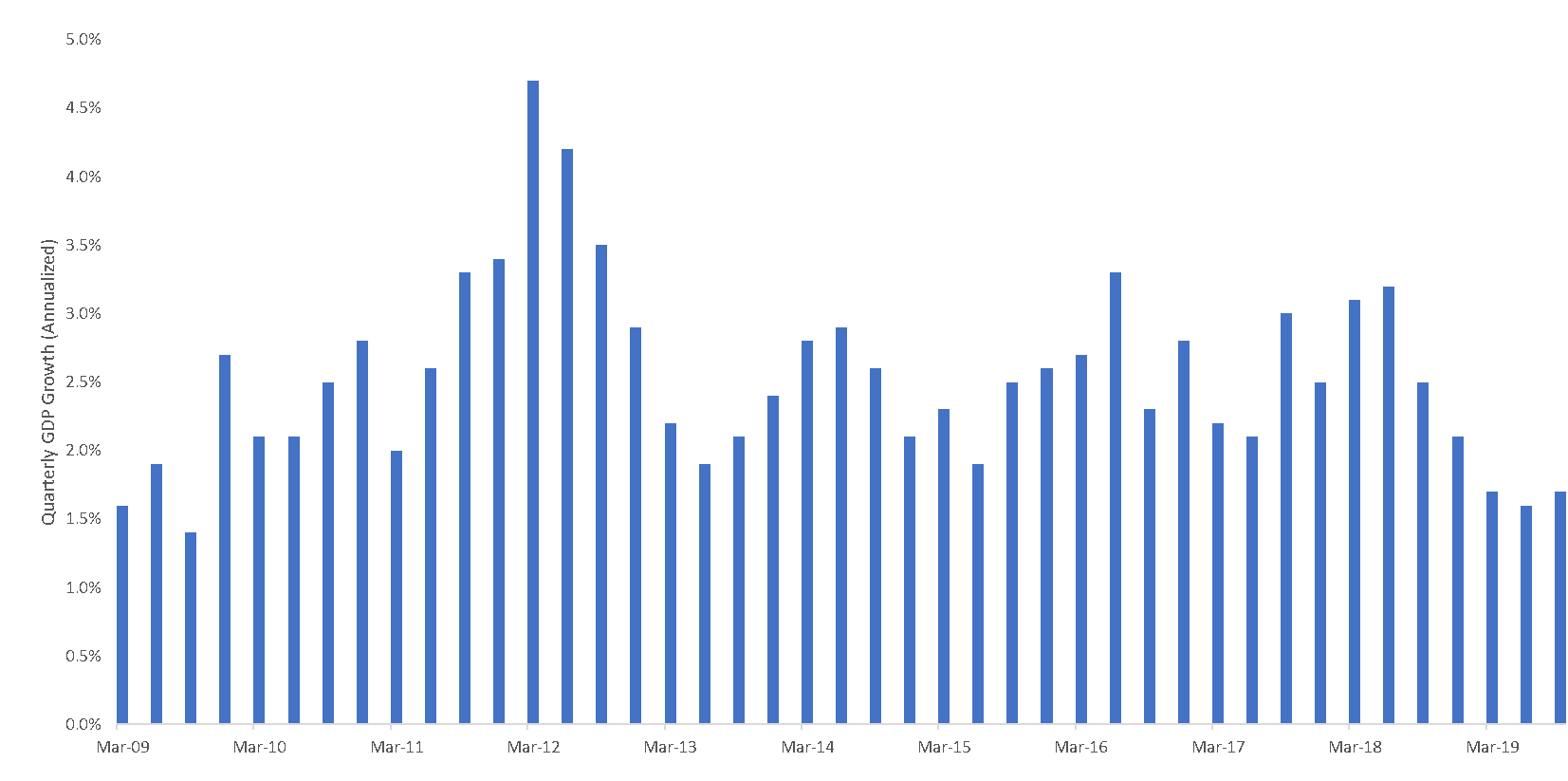

It may seem misplaced to discuss the likelihood of unconventional monetary policy in a country that has registered only three quarters of negative GDP growth in the past 25 years, but a convergence of macroeconomic forces has placed the issue on the Reserve Bank of Australia’s agenda. Until now, extraordinary policy tools such as central bank purchases of assets (i.e., quantitative easing) and negative interest rates have been deployed in economies that have struggled to deliver growth and ignite inflation. Yet, Australia’s economy is slowing, and perhaps worryingly so. After having registered 10 years through December 2018 where annualized quarterly growth averaged 2.6%, the country’s GDP failed to reach that rate during any of 2019’s first three quarters.

Exhibit 1: Annualized Quarterly Australian GDP Growth

Growth failed to reach 2.0%, annualized, in any of the first three quarters of 2019 due to global trade disputes, and prospects for 2020 look even more challenging due to the coronavirus outbreak.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 9/30/19

Growth prospects are expected to only worsen as the global economy grapples with the effects of the rapidly expanding COVID-19 coronavirus. Facing both supply disruptions and demand destruction, monetary authorities have been forced to act, something illustrated by the recent Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) 25 basis point (bps) and Federal Reserve (Fed) 50 bps rate cuts. Authorities in both countries cited the “significant effect” that COVID-19 would have on the global economy. Despite the RBA’s target cash rate sitting at a record low of 0.50%, futures markets expect an additional 25 bps cut at the central bank’s April meeting.

Should that occur, the RBA would find itself effectively at its lower bound for interest rates, thus leaving only unconventional steps as a policy lever.

Even prior to the coronavirus outbreak, the RBA under Governor Philip Lowe was proactive in addressing this slowdown. Late last year he presented his ideas of what form extraordinary policy in Australia may take. While he made clear his preference for purchasing government bonds, many aspects of how such a program would be instituted – and what the economic and market ramifications would be – remain up for debate. Rather than presuming Australian-style accommodative policy would resemble that of other developed markets, one must account for factors in trade and the government’s fiscal position that would likely influence which policy prescription may ultimately be implemented.

While inroads in the U.S.-China trade dispute and last autumn’s stabilization of global purchasing manager indices seemed to have improved the outlook for global growth, the economic contagion sparked by the coronavirus will likely force authorities to explore policy options sooner rather than later.

Headwinds Converging

Acutely threatening Australia’s run of uninterrupted economic growth was 2019’s slowdown in global trade. With China in the crosshairs of U.S. tariffs, suppliers of raw materials to the world’s second-largest economy and main manufacturing hub felt the second-derivative effects of the trade dispute. Yet the trade war only intensified the headwinds emanating from China, namely already slowing economic growth and authorities’ attempts to rein in that country’s recent debt binge. The spillover into Australia’s economy has been evidenced in both coal and iron exports to China well off their 2017 highs.

With economists forecasting dramatically lower Chinese GDP growth in the first and second quarters of 2020, the Asian giant will continue to cast a long shadow over Australia’s economy.

Other factors negatively impacting Australia’s economic prospects are domestic in nature. Household debt as a percentage of GDP is among the highest in the world, eclipsing the levels found in the U.S., UK and Canada. Housing debt as a percentage of housing assets has recently climbed, hinting that consumers’ ability for additional borrowing may be limited. Over the past two years, non-mortgage consumer lending has trended downward, perhaps signifying a shift toward deleveraging. And given the interconnectivity of global markets, Australia is not immune to the low-growth, disinflationary forces that have hampered other advanced economies. Foremost among these are poor demographics and the deflationary effects of technology.

Reigniting Growth

Faced with this backdrop, the RBA has set about identifying countercyclical tools that could be deployed to combat a further slowdown in the economy. With a decade’s worth of case studies provided by advanced economies that have implemented unconventional policy, the RBA has plenty of options to examine. In seeking the appropriate policy, Australian policy makers need to clearly identify their objectives. At the highest level, it’s to spur economic growth. The manner through which it would seek to accomplish this is most likely credit expansion.

Unlike what was experienced by many advanced economies in the throes of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when lenders were afraid to deploy capital, Australia’s current problem is a lack of demand for credit.

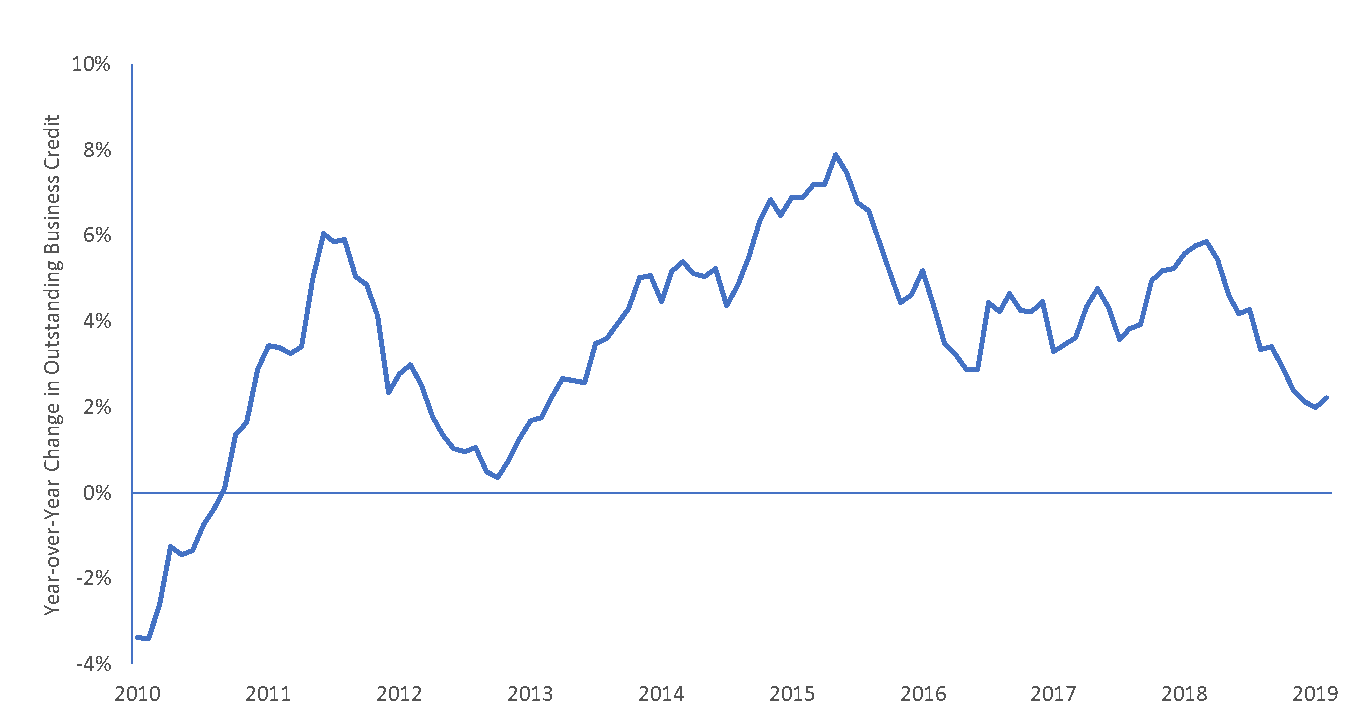

Illustrating this is the considerable slowdown in borrowing by businesses that has occurred over the past year. To remedy this lack of demand, the RBA must set about creating the conditions in which companies view taking on additional debt as an attractive proposition. Perhaps the most direct way this can be accomplished is by lowering the cost of capital to a degree that new investment becomes more compelling. These projects, in turn, would allow funds to circulate into other businesses and, ultimately, translate into higher wages, thus creating a tailwind for the consumer to contribute to economic growth as well.

Exhibit 2: Year-over-Year Change in Outstanding Australian Business Credit

Despite low interest rates, Australian businesses have been hesitant to borrow as seen in the growth of outstanding credit sliding from 6.0%, year over year, to roughly 2.0%.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 1/30/2020

The Right Policy Prescription

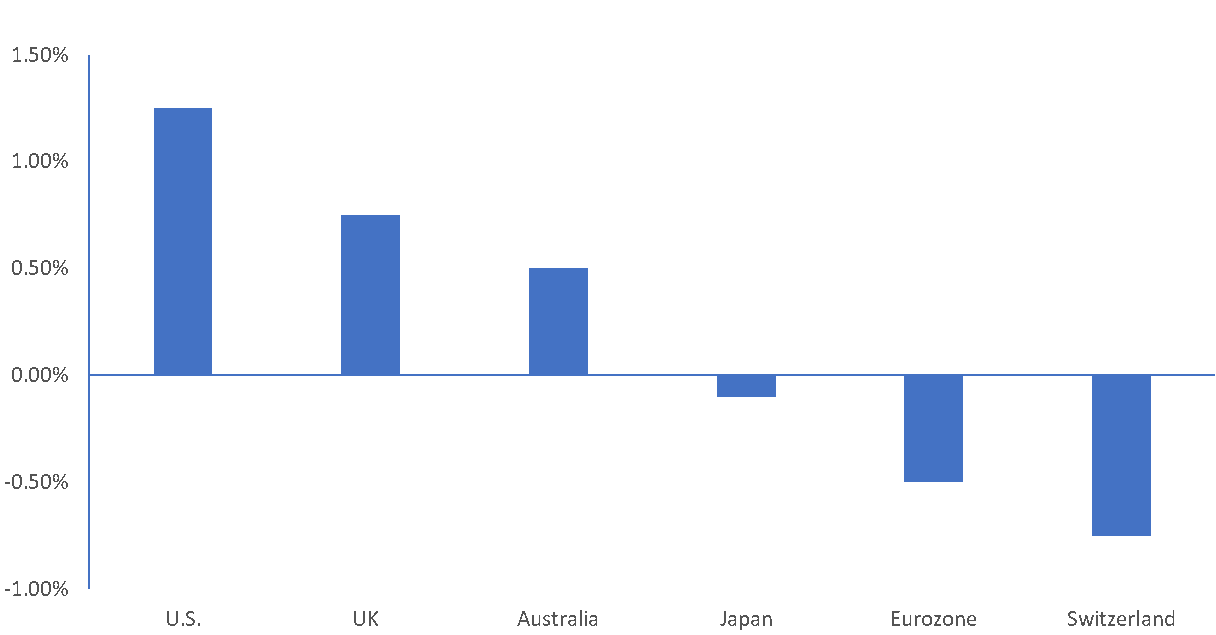

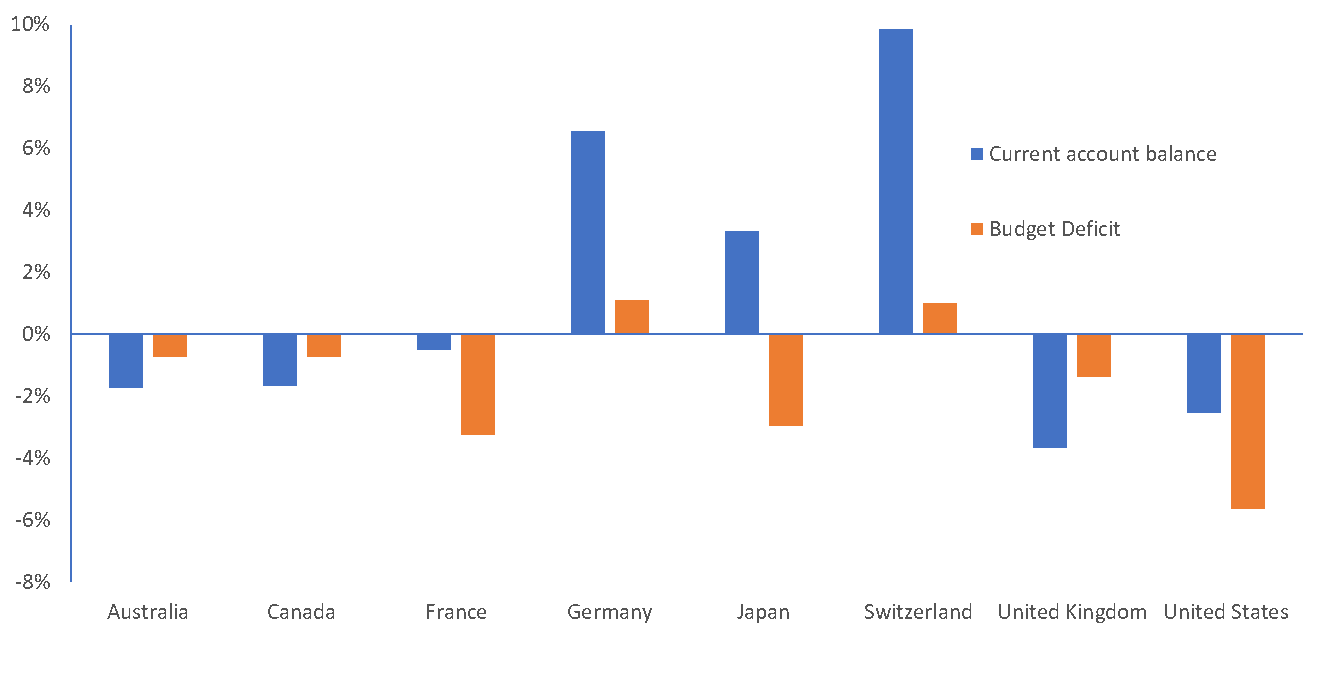

In confronting their own countries’ stagnant growth, central bankers in the U.S., Japan and Europe have largely relied upon two powerful mechanisms: low-to-negative interest rates and quantitative easing (QE). While lowering rates may help the RBA move toward its objective, years of zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) failed to materially ignite growth over the past decade in countries where it was implemented. More recently, authorities have shifted to negative interest rates – charging institutions for parking excess reserves in central banks. This is a tactic that Australia is unable to adopt given that unlike Japan, Germany and Switzerland, it persistently runs a current account deficit, meaning it must keep rates positive to attract the foreign capital necessary to fund its deficit. Positive rates are also necessary to attract overseas money to Australia’s wholesale funding market. As domestic deposits are not sufficient in meeting banks’ funding needs, the promise of positive returns in short-term lending markets is essential in attracting foreign investors to plug this gap.

Exhibit 3: Developed Market Central Bank Benchmark Policy Rates

Australia has room for an additional rate cut, but unlike countries that run current account surpluses, it cannot take its policy rate negative, thus leaving unconventional policy as the remaining option.

Source: Bloomberg, as of 3/3/2020

This leaves the asset purchases that are the hallmark of QE. But this begs the question: which assets? In stating his preference for government bonds, Governor Lowe laid out an argument that this method would be most effective in achieving the RBA’s objectives while limiting any potential ill effects. These purchases would directly lower the cost of funding for the government and indirectly for other borrowers, including businesses and consumers. Furthermore, by purchasing government debt, the RBA would not run up against liquidity restraints and could avoid the negative optics of potentially distorting private markets by picking favored businesses or industries.

Similar to what occurred in other countries, the RBA could buy bonds across a range of maturities, thus lowering rates across the yield curve. Not only would this decrease the cost of credit instruments benchmarked to longer-dated bonds, but also the associated lower yield would likely push investors toward riskier instruments such as high-yield debt and equities, creating more favorable financing conditions for those entities.

A major risk associated with purchasing government bonds, however, is these are the same instruments banks are required to hold as capital buffers.

Should RBA purchases crowd banks out from this market, lower levels of regulatory capital could, perversely, limit the very same credit growth that policy makers are attempting to catalyze.

The Role of the Territories

One way in which the RBA could complement its federal bond purchases, thus reducing the risks posed to banks seeking capital, is to focus part of its purchases on semi-government bonds (semis) issued by states and territories. These securities are often issued to fund infrastructure projects, so in addition to injecting liquidity into the economy, deploying funds via this channel may have the added benefit of increasing national productivity, a necessary ingredient for GDP growth. Also, by still focusing on government borrowers, the RBA could sidestep the issue of weak private-sector credit demand, which may or may not return in a regime of ultra-low interest rates.

Rebuilding the House

Yet monetary policy can only accomplish so much, a point repeatedly made by central bankers during the post-GFC era. Fiscal expansion plays a role as well. One – controversial – way to execute this would be to deposit funds directly into consumers’ bank accounts such as what has just occurred in Hong Kong as authorities seek to stanch economic contraction. This method would put consumers at the fore of growing the economy and counter the trend of them backing away from non-mortgage debt. While this approach has been considered in many economies during various crises, the likelihood of “helicopter money” being adopted in Australia is remote.

Monetary policy can help put out acute fires associated with a slowing economy; it proves, however, less effective at rebuilding the house. A more useful tool for that endeavor is fiscal expansion, which can take many forms. Tax cuts, increases in government transfer programs, subsidies and infrastructure spending all fall into this category. Australia is well positioned to increase government outlays given its relatively more favorable fiscal position vis-à-vis other advanced economies. The country tends to run much lower budget deficits than the U.S., UK and Japan, and federal debt to GDP is far below the levels registered in other developed countries.

Exhibit 4: Developed Market Current Account and Government Budget Balances

While Australia is unable to take interest rates negative due to its current account deficit, it does have more room than other advanced nations to implement fiscal expansion to combat flagging growth.

Source: International Monetary Fund, as of 10/11/2019

A problem with fiscal expansion during periods in which a central bank is the marginal buyer of government debt is that it blurs the line between monetary and fiscal policy, thus potentially compromising the independence for which many developed market central banks are renowned. In extreme situations, a central bank can directly purchase government debt, a concept known as monetization. While a particularly dire situation may call for such measures in the future, we doubt that the RBA would resort to such a drastic step in the current environment.

Inching toward Action

Expectations that headway in trade disputes would lead to a rebound in global growth have proven ephemeral in the wake of the coronavirus outbreak. While certain factors within Australia are supportive of growth, such as increases in homebuyers’ borrowing capacity, income tax rebates, higher wages and resilient iron ore prices, we believe they will not be enough and that the RBA and perhaps the federal government will be forced into action.

While the current administration has the objective of delivering a fiscal surplus by May of this year, we believe that once achieved, authorities will be compelled to increase spending to combat the ill effects of both this summer’s historic bushfire season and the inevitable negative impact on global growth caused by the coronavirus outbreak.

Secular, Not Cyclical

Magnifying the acute risks posed to the Australian economy in 2020 are the secular headwinds that have hampered growth across advanced economies. We believe that, eventually, these will catch up to Australia, especially as the decade-plus boost received from China integrating into the global trading system wanes. With negative interest rates off the table because of persistent current account deficits, the RBA will likely have to keep asset purchases at the ready.

As experienced in countries that have already been down the QE path, such measures will have profound implications for the economy and financial markets. Lower interest rates, flatter yield curves and a weaker currency would each impact investor behavior. Along with raising of riskier assets beyond what is supported by fundamentals, unconventional policy can flatten the yield curve to a degree that hampers lending and puts the finances of insurance companies and pensions under pressure.

Australia has a large and mature bond market. But as has been witnessed in Europe and the U.S. an activist central bank can cast a long shadow on these markets with no guarantee that achieving its stated goals are a certainty. Rather, it is the unforeseen consequences that investors must navigate. We believe it’s not too early for the investment community to consider the ramifications – both good and bad – that Australia QE would have on markets.

Learn more

Stay up to date with our latest fixed income insights by hitting the follow button below.