What the government and RBA can do to save the economy...

We are in the eye of the worst financial storm in modern history, which has vaporised the liquidity of key government bond markets, compelling profound central bank interventions to avoid the outright market failures that I had repeatedly warned policymakers about in late February. In the AFR today, I explain what the RBA and the government can do to save the Australian economy. Click that link to read my column or AFR subs can click here. Excerpt only:

The good news is that Coolabah Capital's data scientists' analysis suggests we might pass through the storm over the next month, which is going to liberate immense investment opportunities. One key turning point will be when the infection and mortality rates recorded in the world’s largest economy, the US, materially decelerate.

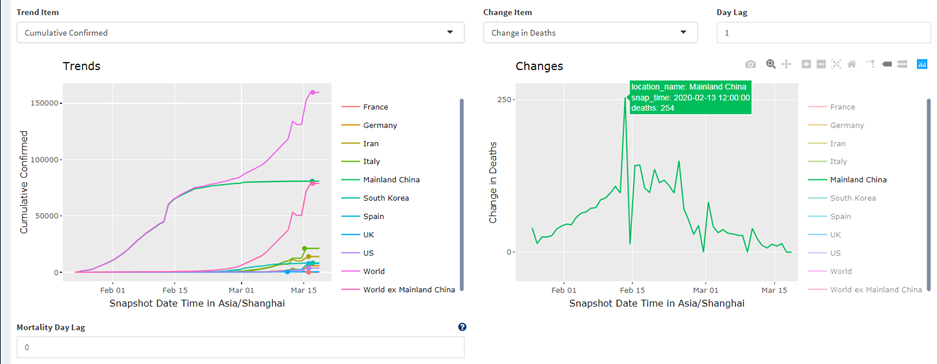

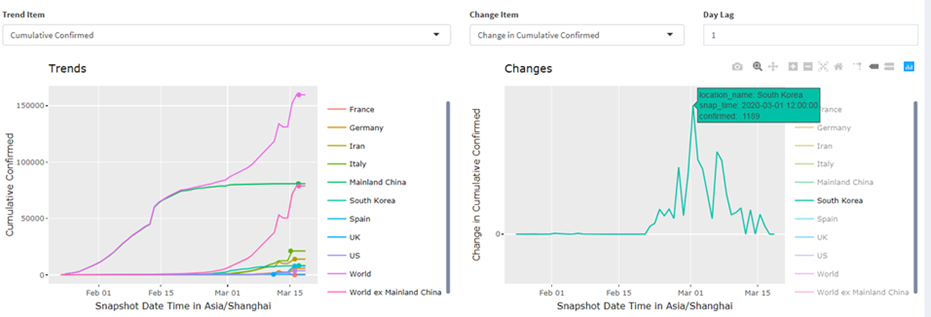

Examining our live data feeds from South Korea and China (excluding Hubei), the peak infection and death rates have occurred within two to three weeks of them noticeably ramping up on a daily basis. This time horizon assumes the US can effectively contain and mitigate the virus as well as the South Koreans have done.

(The images below are screen-shots from our real-time coronavirus tracking systems. The right-hand-side charts show the rapid escalation and de-escalation in Chinese deaths and Korean infections. We trust the Korean data, and have some faith in the Chinese fatality information.)

Two advantages the US has are its geographic dispersion and rapidly rising temperatures as it transitions into summer, which appears to impede transmission. A disadvantage has been poor testing capacity and policy coordination.

A second inflexion point will be when the US government secures an appropriately-sized fiscal stimulus to compensate for the enormous depression in activity that it will experience over the coming months.

The coronavirus has propagated the single-largest globally synchronised drop in demand-side activity since WWII, which is orders of magnitude more significant than the short-term supply chain shocks everyone was fussing over in February. Our real-time monitoring of Chinese traffic congestion levels suggests that most key cities are back online. In places like Shenzhen, traffic activity is now bursting through 2019 levels. Within one month, China will be firing on all cylinders.

The failure of any decent “Trump Pump” in contrast to the fiscal firepower being rolled out in most other developed countries has been a source of tremendous concern for financial markets and the US Federal Reserve, which has finally come to the party with the full-spectrum quantitative easing (QE) that this column was calling for in late February.

Back then we argued that the inability of markets to price the financial consequences of a global pandemic would eviscerate liquidity in all markets, including government bonds, and trigger a rapid solvency crisis. The only choice was for central banks and treasuries to move quickly to coordinate an unconditional "liquidity bridge" via full spectrum QE to span the time gap between now and when vaccines and/or anti-viral drugs are eventually available. Unfortunately, the central banks were slow to move, which has amplified the extreme financial duress. But they have now got the message.

There is nevertheless more Australia’s government and the RBA can do. Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg have handled the crisis adroitly, but the current $17.6 billion stimulus, worth less than one per cent of GDP, is going to need to be upsized substantially. HSBC’s chief economist Paul Bloxham says the government should consider something along the lines of New Zealand’s package, which is worth four per cent of GDP.

One crucial policy challenge is how to convince small businesses to keep staff on, pay wages and rent, and not shut-up-shop. Many governments have addressed this via life-line style loans for SMEs to ensure they can meet overhead over the next six to twelve months. Hong Kong's government has offered to lend SMEs up to A$420,000 to cover wages and rents, which can be repaid over the next three years. It should be straightforward for Australia to develop something similar via one of the major banks where the government provides the funding and the bank administers it.

While the RBA was quick off the mark with the surprise rate cut we expected in March, it has lagged peers on guaranteeing banking liquidity and minimising borrowing rates. One welcome development this week has been opening up longer-term funding options for banks via so-called term “repurchase” (or repo) arrangements of six months or more, which is what it did during the GFC. (It technically classifies this as QE.)

On Monday the US Federal Reserve announced it would purchase at least US$200 billion (A$327 billion) of residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) to maximise the pass-through of its cash rate cuts to borrowers as lenders’ funding costs sky-rocket. Here in Australia we have seen the same dynamic play out.

The major banks’ cost of borrowing via senior bonds has jumped from 69 basis points over the bank bill swap rate (BBSW) in January to about 170 basis points based on current secondary market bids. The cost of funding through their subordinated bonds has leapt from 165 basis points to about 350 basis points above BBSW. And, finally, funding via ASX listed hybrids has never been more expensive for the banks, with credit spreads soaring from 274 basis points to 645 basis points above BBSW.

These spreads are in line with, or above, the worst levels experienced during the GFC, which will eventually feed into a radical reduction in the banks' net interest margins. With deleveraging forcing the major banks’ returns on equity down from 18 per cent in 2015 to around 11 per cent today (in line with their cost of equity), they will have no choice but to pass on additional funding costs to borrowers via higher interest rates, unless they abate.

The RBA can assist during this 1-in-100 year crisis by emulating the efforts of the Bank of England, which has offered almost unlimited four year term funding to all UK banks with incentives for them to make loans to SMEs. This would cost taxpayers nothing while ensuring the banks can continue to make cheap finance available to all borrowers. An express goal of the BoE has been to shield British banks from market-induced funding cost pressures.

A final idea is for the government to roll-out the Treasury’s RMBS investment program, which I helped develop during the GFC to assist smaller banks and non-banks during that funding cost crisis. This is precisely what the Federal Reserve is doing in the US right now. Treasury’s Australian Office of Financial Management (AOFM) could step-up and offer to fund, say, $50 billion or more of RMBS and Asset-Backed Securities (ABS) comprising pools of home loans, SME loans, personal loans and credit cards. The AOFM is already implementing a $2 billion ABS investment focussing on SME loans that I formulated for the prime minister in 2018.

This has several huge advantages. First, it will make money for taxpayers, because the government earns the difference between its cost of borrowing (government bond yields) and the interest paid on the ABS/RMBS, which would equate to a net interest margin of at least 1.2 per cent annually. Second, it will not impact net government debt, because the AOFM will be investing in highly rated asset-backed bonds. Third, it can be rolled out very quickly, as banks and non-banks issue RMBS and ABS every week. Fourth, it can help all types of borrowers, including SMEs, personal loans, auto-loans, credit cards and home loans, which are all securitised. (It should be made available to any lender.) And, finally, it will place significant downward pressure on all borrowing costs if the AOFM’s investment is priced on pre-crisis credit spreads because RMBS/ABS is fungible with other types of funding, such as deposits and senior bonds, that banks and non-banks use to underwrite themselves.

1 topic