What to do with Pre-Crisis Deja Vu

Current conditions are very similar, with high yield debt markets, commodities and emerging markets all suffering. However, equities, property and infrastructure are showing no signs of stress with US equity indices near record highs and some landmark transactions, like the NSW sale of TransGrid, happening at record low yields. Some leading economic indicators are also showing weakness, warning that tougher times could be ahead. Identifying the similarities is the easy part, making decisions about how to invest is the hard part. Here’s my thoughts on how to think and act in light of this pre-crisis deja vu.

Focus on Return of capital

In my August 2014 analysis I used the phrase “weeding and pruning” to describe how to act in light of the high prices then being paid for credit investments. This was an encouragement to get rid of weaker credits and replace them with stronger ones. In the last few months an old adage has become popular again, “I’m more concerned about the return of my capital than the return on my capital”. These two sayings convey a similar meaning; always own securities that will perform well in a downturn as it might be just around the corner. A good investment is typically a business with high prospects of positive cashflow but trading at a reasonable price.

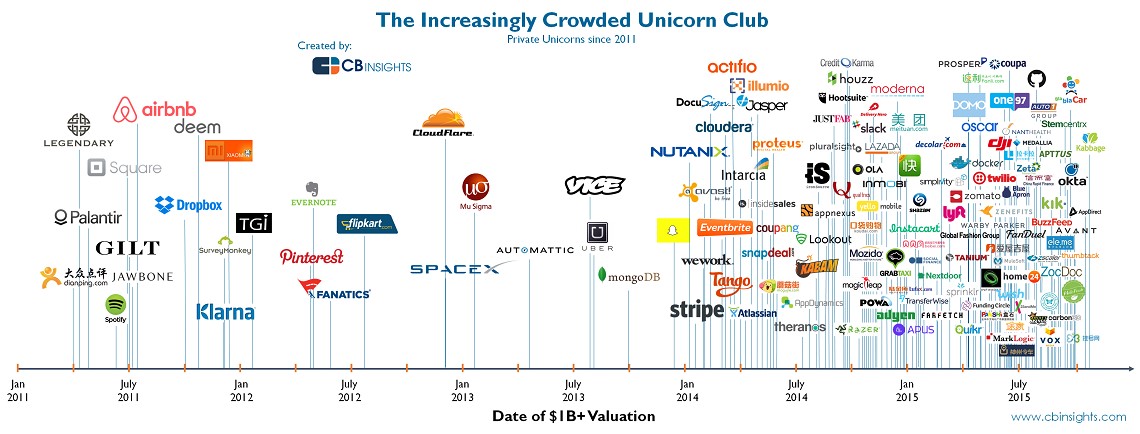

It’s hard not to mention the second tech boom currently underway as a classic example of low prospects of positive cashflows but high valuations. Particularly in the US, lots of tech ideas are being funded, but few have positive cashflows. Many expect there will be a separation of the useful from the faddish tech firms in the years ahead. Firms with a clear way to increase profit and efficiency for others, like Atlassian, will survive but will likely be marked down as the whole sector reprices. Many firms that focus on attracting eyeballs with the hope of figuring out how to monetise that later will disappear. The graph below tracks the minting of new “unicorns”, tech companies with implied billion dollar valuations. It’s hard not to be cynical when so many firms losing so much money reach this benchmark.

Focus on Leverage

It’s no great insight that leverage amplifies returns both for good and bad. But the most often ignored point about leverage is that it’s not just about debt but also the operating leverage of the company and the interaction of the two. Operating leverage is typically defined as the relative split of costs between fixed and variable, with a high level of fixed costs leaving a business unable to reduce costs proportionately as sales decline. However, in a more expansive sense operating leverage includes exposure to volatile revenues and expenses such as commodity prices. For instance, lower oil prices hurts oil producers but helps transport companies, with both being cyclical industries.

Regardless of how strictly operating leverage is defined, businesses with high levels of cyclicality are higher risk. Combining high operational leverage and high financial leverage multiplies the risks and rewards even further. Private equity firms understand this, as they typically only apply high levels of financial leverage to businesses that have low operational leverage. The wave of defaults coming in US high yield is being led by commodity producers and their service providers, where the combined operating and financial leverage is extreme. US retailers, with high levels of fixed costs from their tenancies and high debt levels, are another sector showing high levels of distress.

Focus on Cashflows

One of the subtle signs that investor hubris is creeping back is the predominance of adjusted earnings in company presentations. Companies seek to exclude all sorts of expenses from their profit picture in an attempt to dress up their otherwise meagre results. In some cases, it can best be described as financial lipstick on a pig.

One of my favourite examples of accounting adjustments is Qantas. Alan Joyce became CEO in November 2008 with seven annual results released since then. Every single year Qantas has reported an “underlying” profit before tax which was substantially better than the statutory profit before tax. Over the seven years the underlying profit sums to $1.83 billion compared to $2.84 billion of statutory losses. The difference is an enormous $4.67 billion. On a cashflow basis (including operational and capital expenditures but excluding debt and equity changes) it is still an ugly picture as Qantas has burnt through $20 million of cash in seven years. As a result of the lack of positive cashflow, there hasn’t been a dividend paid since April 2009. Long standing shareholders might well be shouting “show me the money”.

This sort of fudged accounting can also show through in valuation methodologies. Gross yields replace net yields, or valuations may be based on (hoped for) full tenancy/usage rather than the current positon. Property and infrastructure can both be havens for this sort of shenanigans. Gross yields are usually quoted for residential property with rates, maintenance costs, insurance, vacancy periods, stamp duty and agency fees treated as if they don’t exist. In infrastructure the use of EBITDA instead of EBIT or cashflow can be used to hide maintenance costs. These might be near zero on a brand new asset but I’ve seen maintenance costs as high as 40% of EBITDA for aging assets.

One of the reasons I like credit investments is that there’s little room for a fudge factor. Interest is an expense the company must pay or it will be insolvent. There’s very few things that investors need to add to or subtract from either the regular cash received, or the purchase and divestment prices. In the second half of this year I’ve been finding securities at or very close to investment grade, with the expectation of stronger credit profiles over time, paying 6-9% yields. These aren’t particularly complex or risky, but they are somewhat illiquid.

Presume illiquidity and build cash

Another favourite investment idiom making a comeback is “liquidity is always available, until it is needed.” In a time of crisis those with cash benefit and those with a need for it pay the price. Few institutional investors have the luxury of moving to 100% cash if they believe that markets will worsen. However, almost all investors have some flexibility in how much cash they hold and the amount of beta in the non-cash investments they make. Increasing the amount of cash held by selling off high beta assets that haven’t seen much of a reduction in price is arguably the best way to reposition. In Australia, trophy infrastructure and property assets seem the most obvious candidates.

In the current environment I’m using a barbell strategy to manage liquidity. To keep cash optionality high, increased cash levels are supplemented with short dated securities (maximum 3 years) that have a reasonable yield. These short dated securities have a number of benefits, the most important being they will convert to cash in the not too distant future allowing for capital to be reinvested when prices may be lower. In the event that liquidity is needed, near term maturities mean that the discount when a higher credit spread is applied will be less.

The other end of the barbell are Australian securities that pay high returns for low risk, primarily because they are considered illiquid. The additional return earned on these offsets the lower returns on short dated securities and cash. Subordinated securities, preference shares and other long dated credits that are showing limited pick-up for the additional risk are being avoided.

Conclusion

Many investors are seeing the similarities between the current investment conditions and those present in late 2007. An appropriate investment strategy begins with a focus on return of capital, leverage and cashflows. Implementing this strategy should include selling down asset classes that have not factored in the changing conditions and lifting cash levels to take advantage of potential future repricing. Whilst the option value of cash is currently ignored by many, it has the potential to skyrocket in 2016.

Written by Jonathan Rochford for Narrow Road Capital on December 14, 2015. Comments and criticisms are welcomed and can be sent to info@narrowroadcapital.com

1 topic