9 lessons from the scandals that fooled the market

As the old saying goes:

“Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me”.

It’s not just a proverb – it’s a survival strategy. This is especially true for investors.

When it comes to investing, mistakes aren’t just inevitable – they can be expensive. But the worst mistake is repeating them.

Trying to beat the market means taking risks. When you take risks, you’re going to get things wrong. Buffett, Lynch, Templeton, they’ve all found themselves falling victim to this reality; it is unavoidable.

The best investors make sure they learn from them.

Fortunately, there’s a (cheaper) shortcut available to investors – learning from the mistakes of others.

Frauds, scandals, bankruptcies. There’s no shortage of stories of financial tragedy waiting to be consumed and analysed. So, why not take advantage of it?

Let’s take a look at three of the biggest of the last 25 years.

The Bernie Madoff scandal

- Lesson 1: Beware gurus.

- Lesson 2: If it looks too good to be true, it probably is.

- Lesson 3: Trust but verify.

Bernie Madoff went from the private clubs of Palm Beach, Florida, to federal prison.

He was once a high-flying financier and chairman of the NASDAQ stock exchange; he is now more famous for being the mastermind of the world’s largest Ponzi scheme.

At its core is a story of misplaced trust in a person people believed was an investing guru.

Notoriously secretive, Madoff refused to engage with those who trusted him with their capital, even becoming abusive if they tried to ask questions.

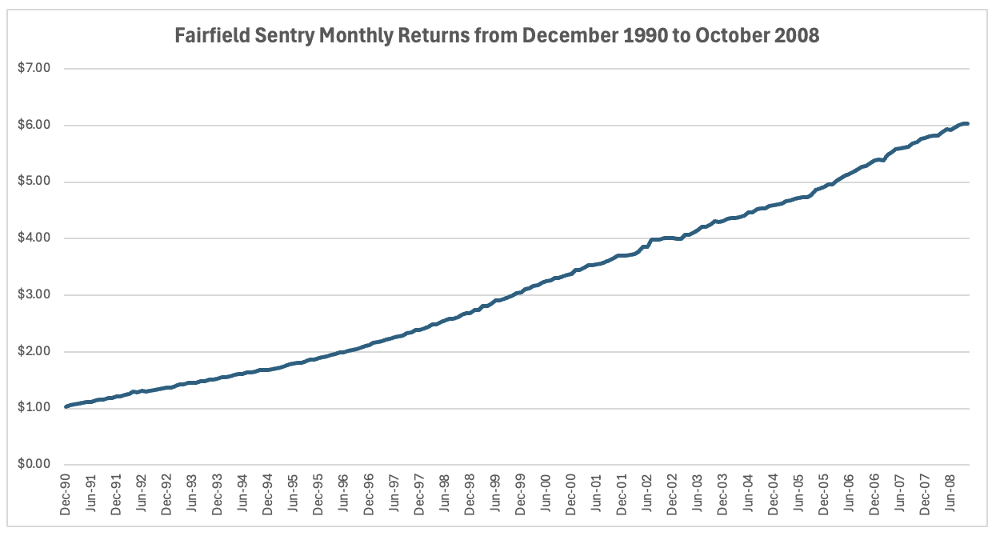

As shown below, in the chart of Fairfield Sentry, a hedge fund that invested 95% of its capital with Madoff, shows, the results were good (or so it seemed). So, it worked. Investors left him alone.

But, as the saying goes, if it is too good to be true, it probably is.

Madoff, it seemed, couldn’t put a foot wrong. Even continuing to generate positive returns during the collapse of the Dot-com bubble, when everyone else lost a fortune.

Not everyone just accepted Madoff’s figures. At least one fund manager, sceptical of the performance, took the time to run the numbers and simulate Madoff’s strategy. The results clearly showed that such performance was impossible.

The SEC and FBI would soon be made aware of this and would be used to convict him.

To summarise, beware gurus, especially if they refuse to shed any light on how they achieve their results. Don’t let greed blind you to incredible claims, even (or perhaps especially) if they are delivered in a way that looks official.

Finally, although a lot of trust is involved in investing, it’s also important that you try to verify, if not try and falsify, claims being made, especially if those claims are big ones.

Suggested watching: Madoff: The Monster of Wall Street on Netflix

Enron

-

Lesson 1: Intelligence can be an asset or a liability.

-

Lesson 2: Culture matters!

- Lesson 3: Although bad numbers can be hidden, they can’t disappear.

Outside of Madoff, Enron is arguably the most infamous scandal of the twentieth century.

Once a boring energy distribution business, it would soon reinvent itself as a flashy, fast-growing energy trader. That is, before it all came crashing down under the weight of dodgy accounting.

Enron provided another example of misplaced trust. This time, not in gurus, but genius.

Enron’s management was considered some of the most intelligent business minds in the world. Which was arguably correct; however, genius can be used for both good and bad purposes, which is what happened here and arguably why it took so long for it all to go pear-shaped.

It also highlights the importance of culture.

The culture inside Enron was hyper-aggressive. It was also one almost singularly focused on keeping the share price going up.

This creates a volatile situation where fraud, where there was not just an opportunity for it to happen, but the incentive to do so and the ability to rationalise it – known as the fraud triangle.

The Enron scandal also showed that, while bad numbers can be hidden, they can’t disappear.

Every time Enron shifted negative figures off its financial statements, it left something behind – such as a declining return on equity, which was used by famed short seller Jim Chanos to spot that something was going wrong and profit from the company’s collapse.

Enron was a story of extremely smart people not realising they were doing dumb things, which was allowed because they created a culture that allowed it to happen. But by digging under the surface and questioning the picture being drawn by management, some were able to spot what was really going on and either avoid the blow-up or, as in the case of Chanos, profit from it.

Suggested reading: The Smartest Guys in the Room by Bethany McLean

Wirecard

-

Lesson 1: A combative attitude to critics is a major red flag.

-

Lesson 2: You really don’t know who you are trusting.

- Lesson 3: You can’t absolve responsibility to regulators.

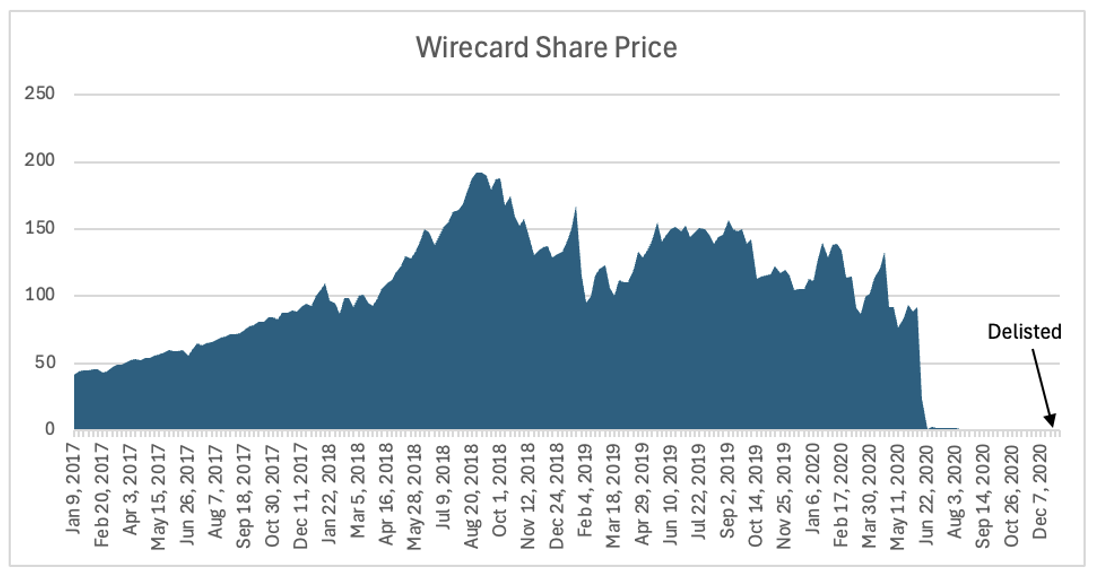

Wirecard was meant to be Europe’s response to Silicon Valley’s monopoly on high-flying tech companies.

However, its captivating tale of soaring revenue growth would eventually be proven an illusion, leading to the company’s collapse.

The most interesting thing is that Wirecard’s nefarious activities weren’t even much of a secret. In fact, the Financial Times had been blowing the whistle on the company as many as six years before the company’s collapse, which you can read about here.

So why did so many people fall for it?

Wirecard took a very combative approach to critics.

They made the market question the motives of those calling out the company. Wirecard were the good guys in this story, fighting a cabal of short sellers and market manipulators.

This is regularly a red flag. A business that is performing well and has nothing to hide doesn’t need to attack critics. Business performance will prove them wrong eventually.

Wirecard also highlights the fact that you really don’t know who you are investing in.

Jan Marselek, Wirecard’s chief operating officer, was seen as a bit of a boy wonder. Today, he is one of Interpol’s most wanted and is alleged to be an asset of Russia’s intelligence services.

Warren Buffett can say that he will only invest in management he trusts. His clout means he gets to meet and get to know these people.

For the average investor, this isn’t the case. Made even harder by the fact that CEOs and other key managers are also very good salespeople. They are easy to trust, even when you shouldn’t.

You also can’t absolve the responsibility of protecting yourself to regulators. You are the only person who is really looking out for you.

Wirecard proved this more than any other story. Germany’s financial market regulator was given all the information they needed to clamp down on Wirecard; instead, they investigated the Financial Times and other whistleblowers for alleged market manipulation.

They would issue an apology, but not for many years.

Wirecard was a captivating tale of technological disruption built on a bed of lies. It lasted for as long as it did as the company managed to silence its critics, partially helped by regulators, and change the narrative.

Don’t fall for it.

Suggested reading: Money Men by Dan McCrum

5 topics