Battery Age Minerals: Undervalued, uncovered, unmissable

As the world scrambles to secure dominance in artificial intelligence, one obscure mineral has quietly soared more than 450% in price - largely under the radar of most investors.

Germanium, a rare semiconductor element critical to fibre optics, infrared sensors, and AI data infrastructure, is now effectively embargoed by China, which controls around 75% of global supply. With Western demand accelerating and supply evaporating, prices are spiking, and strategic interest is rising fast.

Yet few listed companies outside of China have meaningful exposure to this vital resource. One little-known Australian miner - Battery Age Minerals (ASX:BM8) - may be sitting on one of the highest-grade germanium deposits in the Western world. Based on current prices, the estimated value of germanium in the ground could range from US$10–15 billion, yet the company trades at a market cap of just A$17 million.

In this piece, we explore why germanium may become the next critical chokepoint in the AI arms race, and why Battery Age Minerals could be one of the most asymmetric investment opportunities hiding in plain sight.

Germanium Basics

Germanium (symbol: Ge) is the 32nd element on the periodic table. It was first discovered in Freiberg, Germany, by chemist Clemens Winkler, who patriotically named the element after his home country.

Germanium is a rare metal, typically found as a byproduct of zinc mining. Its supply is highly concentrated in China, which dominates both the mining and refining of the element. While estimates vary, China is believed to produce around 75% of the world’s germanium. Outside of China and Russia, the largest Western producers include Teck Resources (through zinc byproducts), and Umicore and Boliden, both of which focus primarily on recycling.

What makes germanium unique among critical minerals is its strategic importance across several future-facing industries. Roughly 40% of global demand comes from its use in fibre optics and optical transceivers, used in the data centre and AI buildout. Another 20% is driven by high-tech infrared and military-grade camera systems. It is also a key input in certain solar panel technologies. When combined with silicon, germanium is used to manufacture high-end semiconductors and radio frequency chips.

Given its role in artificial intelligence, defense, telecommunications, and clean energy, germanium is becoming increasingly central to the race for global technological supremacy.

The Geopolitics of Germanium

In December 2024, China introduced a new export licensing regime that effectively banned the export of germanium. As of last month, several of China’s largest germanium producers noted in their mid-year earnings reports that obtaining an export license had become virtually impossible. Market rumours even suggested that Chinese authorities raided the offices of a major rare earth exporter to enforce the ban and ensure no germanium or optical components were leaving the country.

Why such a hard stance? China recognises germanium’s strategic importance. Just as the US has restricted the export of NVIDIA’s most advanced AI chips to China in an effort to maintain a technological lead, Beijing’s germanium export ban serves as a countermeasure. The policy not only advances the Chinese Communist Party’s ambition to lead the AI race, but also hampers the US defense industrial base, which relies on germanium for applications such as military drones and infrared optics.

The impact has been stark. Chinese germanium exports have collapsed, with shipments for certain applications falling by more than 90% compared to pre-restriction levels. Simultaneously, China’s imports of germanium have surged, rising by an estimated 60% year-over-year. This underscores China’s urgency to secure supply for its domestic needs, particularly in defense and AI-related industries.

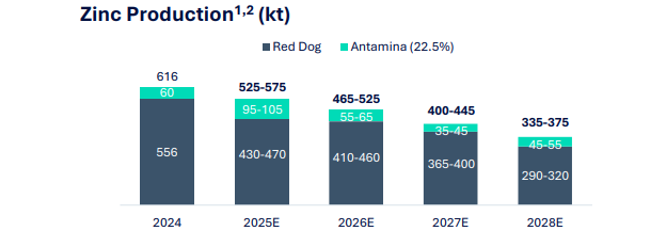

At the same time, Western sources of germanium are under pressure. The largest non-Chinese supplier, Teck Resources, has flagged a 20% annual decline in zinc output at its Red Dog mine, one of the world’s key sources. Since germanium is a byproduct of zinc mining, this decline is expected to result in a comparable drop in germanium production, further tightening an already constrained market.

Source: Teck Resources July 2025 Company Presentation

It comes as no surprise, then, that western prices for germanium have surged, rising from approximately US$1,000/kg to over US$5,500/kg. The market is facing a classic supply-demand imbalance, and no major new supply sources appear imminent. While Ivanhoe’s Kipushi zinc mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo is ramping, China owns and controls more than half of the offtake. The only potential increase may come from Korea Zinc’s memorandum of understanding with Lockheed Martin, though details remain vague. It’s still unclear whether this deal pertains to refining only rather than upstream mining, and even optimistic projections suggest commercial production wouldn’t begin until 2028 at the earliest.

Bringing on new supply is difficult. Germanium is typically found in trace amounts as a byproduct of zinc or coal mining. If those primary resources are uneconomic to extract, then recovering germanium becomes commercially unviable. This makes germanium inherently supply-constrained, with very few viable sources outside of China.

On the demand side, while companies like Corning and Lightpath are working on next-generation alternatives to reduce reliance on germanium in fibre optics and infrared sensors, the reality is that germanium remains critical for premium applications. For example, Corning, the largest Western supplier of optical fibre in the world has germanium in every single one of its products. This includes optical interconnect products within the datacentres as well as fibre optics that join datacentres together. When alloyed with silicon, germanium produces industry-leading reflective coatings essential for high-speed optical interconnects and transceivers, which underpin the bandwidth capacity of AI data centres. Corning’s enterprise business, which serves data centres around the world, has been growing around 80% year-over-year. Importantly, germanium represents only a tiny fraction of total product cost, meaning end users are relatively price inelastic. No other element reflects light as effectively as germanium. Germanium’s refractive properties make it practically impossible to replace in next-generation fibre optics that demand faster speeds. Even at elevated prices, demand remains robust.

Even if the West were to develop substitutes, Chinese demand is expected to rise substantially, driven by its military, drone, and AI ambitions. With supply declining, no significant new projects on the horizon, and structural demand growth from next-generation industries, we believe germanium prices are likely to remain elevated for a long time.

The BM8 Opportunity

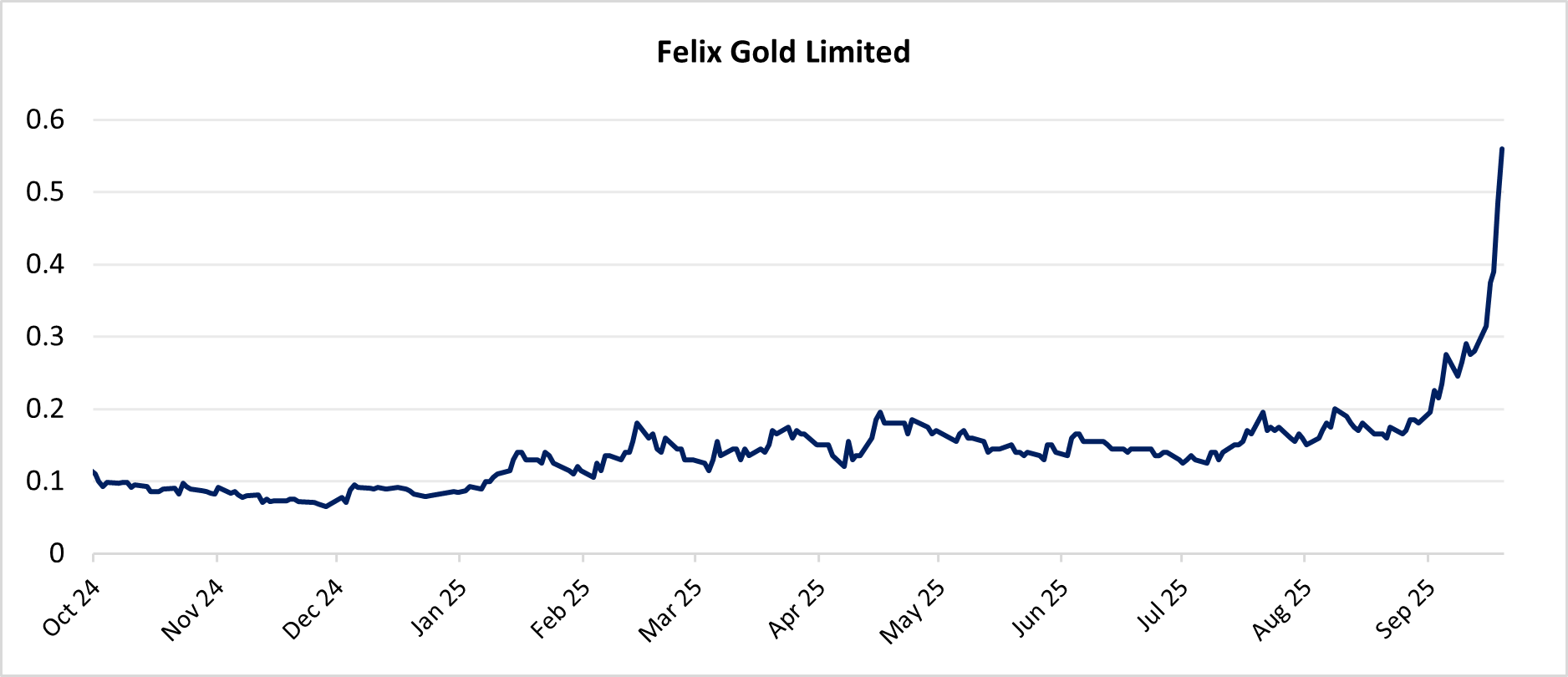

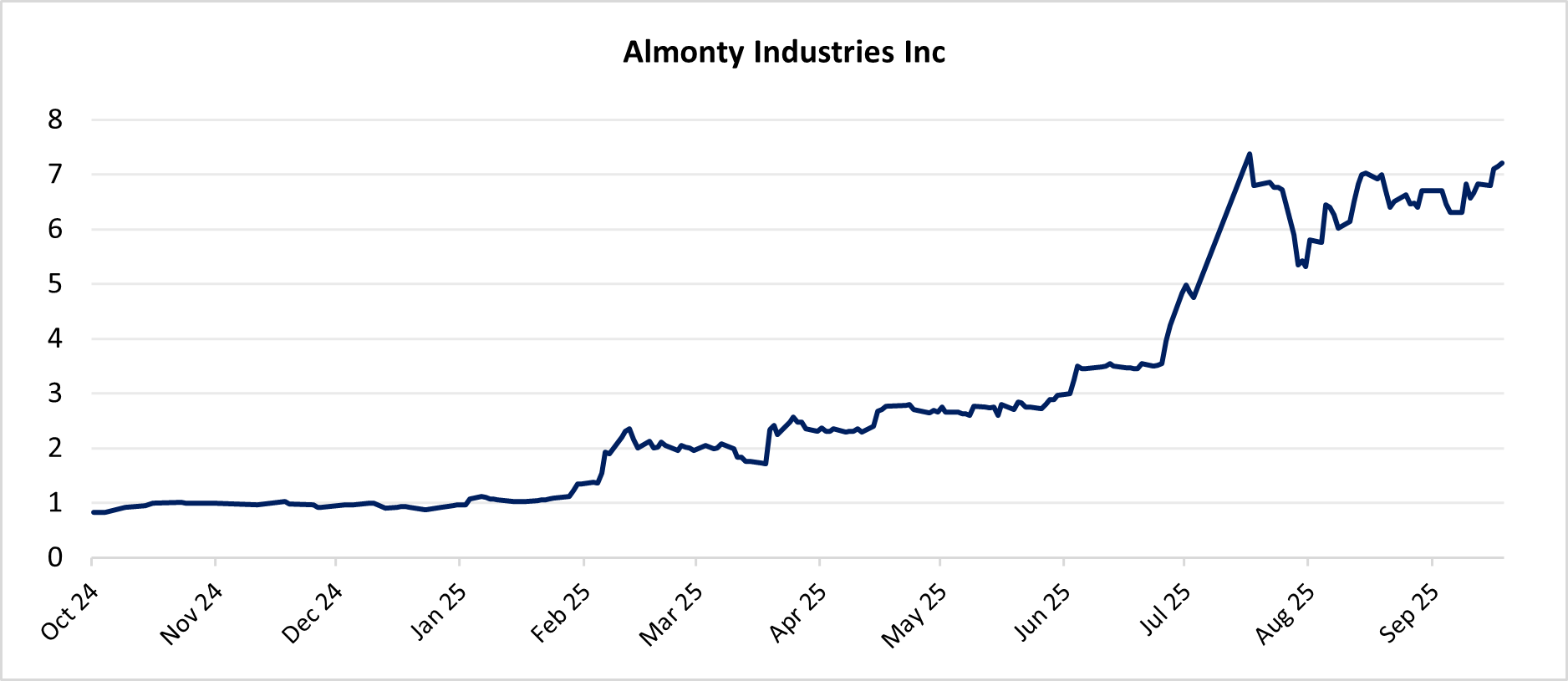

We’ve seen several mining companies deliver outsized returns by being in the right place at the right time, particularly when (i) geopolitical forces disrupt supply chains, and (ii) genuine shortages emerge in critical minerals. Felix Gold’s (ASX:FXG) success during the antimony shortage, and Almonty Industries’ (ASX: AII) rise amid the tungsten disruption, are two recent examples in our own portfolio.

Source: YahooFinance

With germanium, we believe the stakes are even higher. Unlike antimony or tungsten, germanium is deeply intertwined with the AI arms race, robotics, autonomous systems, and national security priorities. As countries race for technological and military dominance, control over germanium supply chains may prove pivotal.

Yet, investible opportunities are scarce. Few listed companies offer pure-play exposure to germanium, and in most cases, it’s a minor byproduct, not the core value driver.

That’s what makes Battery Age Minerals Ltd (ASX:BM8) such a compelling opportunity.

Among its three projects, BM8 owns the Bleiberg zinc-lead-germanium project in Austria, a site with historical pedigree and uniquely high-grade germanium concentrations. Crucially, this is one of the highest-grade known germanium deposits in the Western world, outside of China and Russia.

While management conservatively estimates current germanium grades to be around 200 grams per tonne, recent technical studies released in April 2025 show that the last-mined grades exceeded 1,500 grams per tonne. That’s an order of magnitude higher than many competing projects. Additionally, previous mining stopped at certain fault lines because they lacked the technological equipment back in 1993, but the highest grades of germanium tend to occur in these areas which are now more readily accessible.

The mine was previously shut due to uneconomical prices amid a flood of Chinese exports, but with today’s radically different geopolitical and pricing landscape, this asset has become strategically valuable. In our view, it represents one of the few credible, near-term pathways to meaningful Western supply of germanium.

At current germanium prices, and based on BM8’s ownership interest in the Bleiberg project, we broadly estimate the in-situ value of the germanium resource to be between US$10-15 billion. A JORC-compliant resource estimate, once completed, will help narrow this range and provide more certainty. However, even with conservative assumptions, the mismatch between asset value and market capitalisation is stark.

Importantly, BM8 has just received expedited approval to commence drilling at Bleiberg. This campaign could confirm historical production grades, which, if validated, may serve as a key catalyst for a material re-rating of the stock. Given that the current market capitalisation is only around A$17 million, we believe the embedded option value on the resource is not yet reflected.

BM8’s management team is heavily invested, and appears to share this view. Rather than raising capital through traditional placements, the company is prioritising funding via at-the-money options, which we interpret as a strong signal of internal confidence in the asset.

From our perspective, the risk-reward looks compelling. Yes, BM8 will likely need to raise capital at some stage to advance development, but even after factoring in dilution, the value of the metal in the ground far exceeds the company’s market cap and estimated capex requirements.

To put this in perspective, Felix Gold, which is much closer to mining its antimony resource in Alaska, has an estimated in-situ value of around US$500 million. It currently trades on a fully diluted valuation of approximately A$220 million. By contrast, BM8’s in-situ germanium valuation is 20–30x larger, yet its fully diluted valuation is just ~A$20 million.

The market is clearly pricing in a long lead time before extraction begins, but we’re comfortable with that. As outlined earlier in this note, we believe germanium prices are likely to stay elevated for years. In our view, the disconnect between long-term fundamentals and near-term valuation offers an attractive opportunity. We believe a market capitalisation closer to A$150 million would more appropriately reflect the option value of the Bleiberg project, even without full development certainty.

Risks

The primary risk to this investment case would be a geopolitical breakthrough, whereby China agrees to resume exports of germanium to the US or Europe as part of a broader trade deal. We view this outcome as unlikely, for several key reasons:

- Strategic value: The Chinese government views germanium as more strategically important than other critical minerals like rare earth magnets, due to its applications in AI, optics, and defence. It is seen as a lever in China’s broader strategy for technological sovereignty.

- Low political cost for the US: Unlike rare earth magnets, germanium is less politically salient for the US. Its exclusion from a trade deal would come at minimal domestic cost to the Trump administration, reducing pressure to negotiate its inclusion.

- Unlikely quid pro quo: A potential “chips-for-rare-earths” swap, where China resumes germanium exports in exchange for US chip exports (such as NVIDIA’s high-bandwidth AI chips), seems improbable. The US export ban on AI chips is driven by national security concerns, and policy signals suggest no change in stance is forthcoming.

- Precedent and timing: The original export controls on germanium were introduced prior to the current US-China trade escalation, suggesting that the ban is strategic rather than retaliatory. This strengthens the case that it will remain in place for the foreseeable future.

A secondary risk is technological substitution, specifically, the development of alternative materials that could replace germanium in high-performance optical interconnects or infrared camera systems. Some firms, like Lightpath, have acknowledged growing interest in germanium-free solutions. However, they have also reported that demand for their traditional germanium-based products has softened due to their inability to secure new supply. They also confirm that there is no other material that has the superior refractive index of germanium, which will become even more important as AI demands greater bandwidths.

Our base case remains that Chinese demand for germanium across AI, defence, and automation use-cases will far outpace any decline in Western demand due to substitution.

Conclusion

In our view, Battery Age Minerals remains significantly mispriced given the strategic importance of germanium, the high historical grades at Bleiberg, and the asymmetric risk-reward ahead of drill results. We expect the company to re-rate substantially as broader awareness grows around its unique positioning and as the drill campaign confirms the existence of a high-grade resource that once helped supply much of Western Europe.

In our judgment, there is a significant chance that germanium becomes the critical mineral that holds up the Western AI infrastructure buildout. When this occurs, we believe the market will search for other sources and the stock will re-rate.

5 topics

3 stocks mentioned