Cash rates up by 2023? Not bloody likely

The impressive recovery in the Australian labour market has brought forward expectations for the timing of the RBA’s first cash rate hike. Earlier this month, the RBA indicated that it did not expect cash rates to rise ‘until 2024 at the earliest’ and remained committed to a 3-year government bond yield of 10bps. However, a surprising employment growth outcome for March, which was subsequently announced, left the market questioning the strength of its convictions.

We believe that the conditions required to shake the RBA’s convictions remain unlikely to emerge.

Any hint that the RBA is softening its expectations that rates will not rise before 2024, at the earliest, will lead to an upwards revision of the expected path of cash rates and downwards revision to quantitative easing activities. Yields for bonds maturing after April 2024, which are the current focus of its yield curve control activities, would rise considerably relative to current levels. It is likely that the AUD would rise and credit spreads would widen in that event.

After the RBA’s April meeting was held, the Australian Bureau of Statistics released favourable March employment figures. These showed some 70,700 jobs were added, unexpectedly drew the unemployment rate to 5.6% and brought the level of employment and hours worked above where they were a year ago. This was an unambiguously strong outcome.

We have considered the circumstances required for the RBA to step away from its commitments and do not find any reason that it would change its current guidance as a result of this development.

Further, while not as certain, we believe the likelihood that the RBA will move its focus on yield curve control to the November 2024 bond are at least 50%, which is presently higher than market pricing and commentary infer.

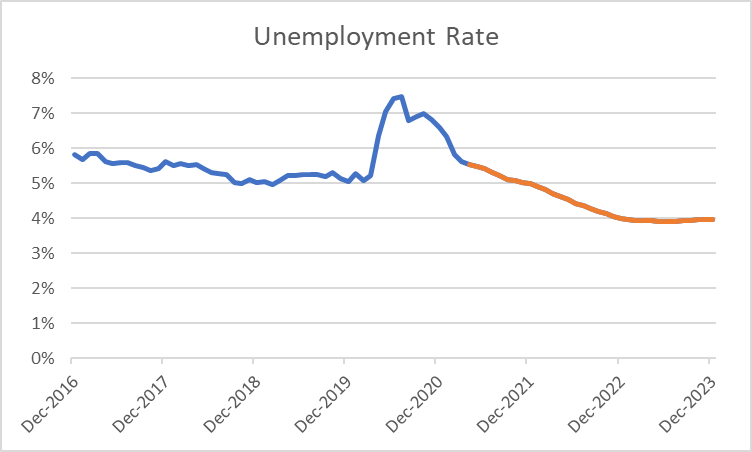

The target unemployment rate is presently around 4%

The RBA has indicated it will not shift rates until CPI is sustainably within its target band of between 2% and 3% per annum. This requires that actual annual inflation exceeds 2% and wage inflation is sustainably at least 3% per annum, the difference is based on expectations for future productivity growth and associated economic relationships.

The above outcomes are clearly minimum conditions and it is unlikely, given the low levels of price inflation and real wages which have been experienced for nearly five years, that the RBA will seek to slow the economy upon reaching this low threshold. More likely, the RBA will want to see expectations for wage and price inflation re-establish at higher rates and allow wage growth to reach a figure like 4% per annum, which is more consistent with a CPI outcome that is sustainably towards the middle of the target band.

Treasury has recently revised its non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) estimate to between 4.5% and 5%. This infers that unemployment must reach lower levels to generate the desired rate of wage inflation. The RBA has also been placing a great deal of significance on achieving full employment. Consistent with this, it has indicated that an unemployment rate of around 4%, possibly lower, may be required. They point out that our pre-covid unemployment rate of 5% was not sufficient to generate the desired rate of wages growth and that the US was only able to generate these outcomes when unemployment reached around 4%.

Forward guidance is at risk if unemployment is expected to reach 4% by the end of 2022

The RBA is committed to achieving sustainable wage inflation, a goal that can be linked to an unemployment rate of 4%. This means an assessment of the likelihood of the RBA softening its stance can be obtained by examining the prospect of unemployment reaching this level by around the end of 2022. This outcome would be expected to deliver the targeted level of inflation by 2023 and provide the earliest reasonable timeframe where the RBA can remain consistent with its policy objectives while stepping away from its current forward guidance.

An optimistic pathway for unemployment, which is now circulating more widely, calls for a 5% unemployment rate by the end of 2021. A pathway that is consistent with this outlook and an unemployment rate of 4% by the end of 2022 is:

Source: ABS, Author calculations

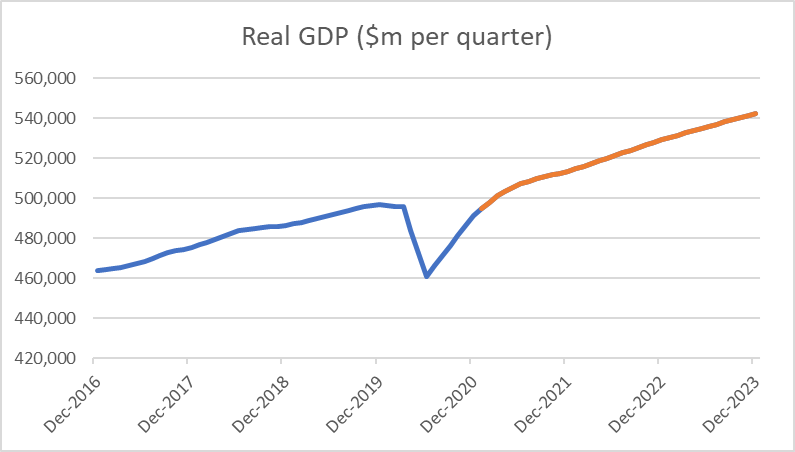

GDP growth expectations are similar to those experienced during the Pre-GFC era

To assess the likelihood of this outcome, we examine the chain of events required to achieve it. First, we begin with the current GDP consensus forecast, which depicts a near-full recovery to the pre-covid trajectory over the projection period, a remarkable outcome, especially in the context that our working population growth has not been supported by net migration for over a year and open borders remain a distant notion.

Source: ABS, Author calculations

The rebound is supported by significant government stimulus, together with pent up expenditure and business investment. However, unlike in the US, the Australian fiscal package is not calibrated to push growth beyond these relatively favourable outcomes. In contrast, Treasurer Frydenberg has indicated that fiscal consolidation would become a priority once unemployment was ‘comfortably’ below 6%. If unemployment is to reach 4% by the end of 2022, government expenditure and the effect of automatic stabilisers will drag on growth.

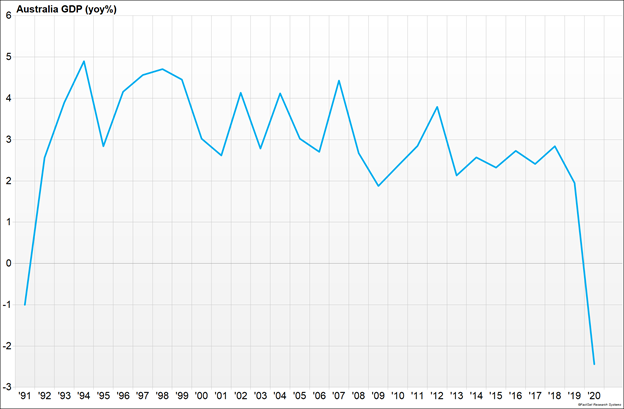

Even if we allow for a very strong Q1 2021 GDP outcome, substantively closing the gap to the pre-covid trajectory, the remaining period to end 2023 shown in the projection would need to be around 3% per annum. During the last 30 years, these outcomes were only achieved against a backdrop of an emergence from the recession of the early 1990s and extraordinary credit creation from that point to the GFC in 2008 which funded strong cycles of housing price movement and dwelling investment over the period. It also financed significant growth in household spending which, in turn, stimulated business investment. Growth rates above 3% per annum were also supported by the generational Chinese-led resource super-cycle in mining investment, whose final burst is visible in 2012:

Source: Factset

These outcomes will be difficult to achieve but are not overtly unreasonable when viewed as merely returning GDP to the pre-covid trendline.

Apart from covid and geopolitical risks, the most obvious challenges to the forecasts are APRA’s preparedness to tolerate a credit boom again and the absence of a clear driver for another very large commodity super-cycle.

Nonetheless, household balance sheets are strong, and businesses have under-invested for many years, which may provide a springboard for immediate growth.

Labour market dynamics required to achieve 4% unemployment by end 2022….defies belief

It should be noted that economic growth has been supported by the contribution from net inwards migration. This averaged 1.5% per annum over the period shown above. For unemployment to be driven to low figures, GDP growth would probably need to be supported by a workforce that is growing more slowly than this. Indeed, it will take some time for international travel and migration to revert to prior levels. To create a scenario that supports the optimistic path for unemployment, we assume that travel will remain highly restricted for the rest of this year and gradually revert to a 1.5% per annum rate in late 2023.

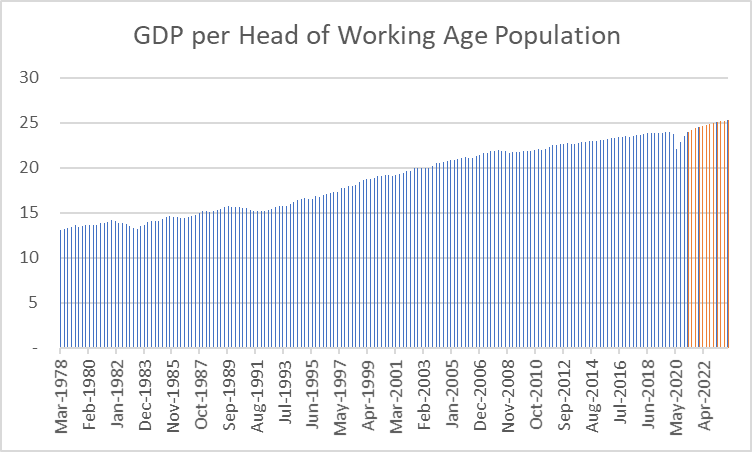

To achieve these outcomes, several other features of the labour market must combine. In the aggregate, GDP per working-age head of population would need to accelerate at the fastest rate since the mid-90s:

Source: ABS, Author Calculations

This is generally achieved by a combination of:

- Increasing the participation rate;

- Increasing the proportion of the labour force which is employed;

- Increasing the hours worked per employed person; and

- Increasing the productivity per working hour.

However, if workers are prepared to work more hours and are more productive with their time, less will be required to accomplish the task. In order to drive unemployment down in the coming years, it is better for factors like participation rate, average working hours and productivity not to grow too much.

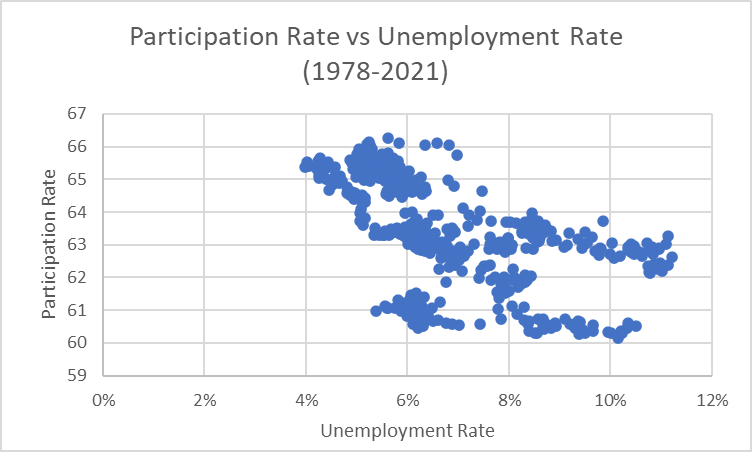

Working through each point, we note that participation rates tend to rise as labour markets tighten:

Source:

ABS

Also, as the labour market tightens, those wanting to work more hours are able to find additional employment and work longer hours on average. Additionally, business investment tends to lag an increase in productivity and, yet, in order to drive unemployment down, productivity per worker must not rise too much.

In order to generate the unemployment pathway consistent with an early cash rate rise, it is necessary to underplay the observed historical relationships. Specifically:

- The increase in the participation rate must not even match trend growth rates associated with increased female and part-time participation in the workforce;

- Average hours per employed worker must not increase by more than 0.5%, from the March 2021 figures, despite underutilisation rates currently remaining well above what is required to engage wage tension; and

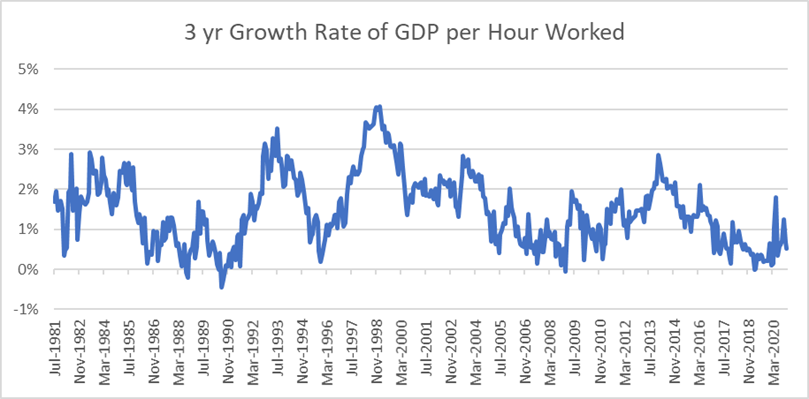

- Productivity only rises by 1% per annum, below Treasury’s assumed longer-term figure of 1.5% per annum and significantly lower than the levels associated with generating significant growth in non-mining business investments in the 1990s:

Source: ABS, Author Calculations

For the optimistic scenario to be plausible, the Australian labour market must already be at a juncture where there are relatively few discouraged workers outside the workforce and workers are generally satisfied with their hours. This is not consistent with market observations which show that an elevated level of underutilisation remains in the labour force, and other research demonstrating that workers who lose their jobs tend to exit the workforce for a while rather than join the unemployed.

Furthermore, a significant shortfall in Australia’s economic performance arose from the sudden stop to educational and tourism exports and we will need students and tourists to return in order to complete our economic recovery. Population growth is also necessary to support significant dwelling investment and reduce the risk of creating an overhang which could create concerns for financial stability. It would contribute to a boost to demand that may spur business investment further. Borders need to be more open than we have generated for this scenario and there will be pent up demand for migration movements. Exceptionally low population growth is somewhat inconsistent with the level of economic growth currently embedded into market expectations.

The requirements to achieve a 4% unemployment rate by 2022 and create the conditions for the RBA to lift rates by 2023, given the current consensus outlook for growth and an imperative for fiscal repair, do not appear plausible.

Extrapolating the clearance of backlogs?

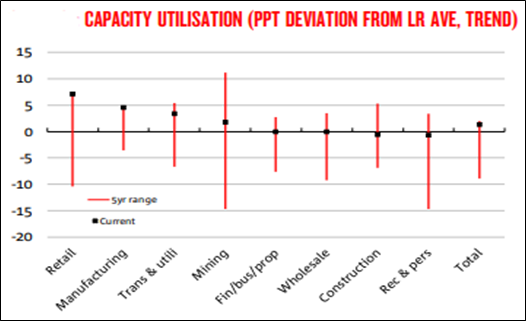

The economy has returned to form exceptionally quickly and there are significant backlogs of demand which need to be cleared. Unsurprisingly, the capacity utilisation of the goods sectors which were most severely affected are now at highs:

Source: NAB March 2021 Business Survey

This upswing in capacity utilisation is unlikely to be sustained and improvements in employment arising from releasing pressures in the supply chain should probably not be extrapolated beyond the next few coming months.

An ongoing fiscal drive could get it done

One catalyst that could improve the probability of an early rate rise is a revision to the commitment towards fiscal consolidation in the near term, even if unemployment rates decline further. If Treasurer Frydenberg elects, as for the US, to retain high levels of ongoing fiscal support to drive economic growth beyond levels considered to be sustainable in the next few years, an early rise would become likely.

Conclusion

The exceptional recovery in Australia’s labour market and the economy more generally is excellent news.

While the outcomes are certainly better than the RBA expected when first making its commitments to avoiding rate rises before 2024, it remains unlikely an early rate rise will occur unless substantial fiscal support remains in place to drive unemployment down. This is not the Government’s stated position.

More immediately, the RBA will consider whether to roll its yield curve control efforts forward from the April 2024 government bond to the November 2024 bond.

We estimate that markets currently assign a likelihood of far less than 50% to this. Should the RBA not extend its forward guidance by around August, the yield curve beyond the April 2024 bond will experience a material rise as expectations for QE will likely be wound back as well.

Given the Government’s commitment to fiscal consolidation and the RBA’s intention to re-anchor wage and price inflation outcomes at higher levels, the RBA is very unlikely to lift rates at the earliest time that CPI records a result within the target band.

It will also be cognisant of the path of US rates, where the Fed has committed to allowing an overshoot of inflation, out of concern for the AUD rising in an unhelpful way. Before lifting cash rates, unemployment will need to fall to close to 4% and remain there for some time. This remains very unlikely to be achieved before 2024.

We expect the RBA to retain its commitment to this language and believe the likelihood of extending the yield curve control commitment is higher than the market anticipates.

Realm is your partner

Our clients are our lifeblood. With deep experience investing in Australian Credit and Fixed Income markets, Realm is result-oriented. We are always focused on delivering client outcomes. Click the 'FOLLOW' button below to receive our insights.