Central banks are not truly independent anymore

As is often the case, forecasting the outlook for interest rates or inflation or the economy generally for the year ahead is never easy. More difficult is the forecasting of short-term returns from asset classes. Often asset prices and economic activity diverge, with expectations or sentiment overtaking economic reality.

However, it is generally the case that the longer term is clearer to see than the short term. Over the long term, the world economy invariably grows, and that is what ultimately drives asset values higher and returns to investors.

For the rest of this decade and beyond, the world economy will steadily grow as hundreds of millions of people in developing or emerging economies across the world progressively move up the income curve. Historically, global economic growth averages around 3.2% per annum. Across Asia and in particular India, Thailand, Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia, the standard of living will continue to lift. In Australia, following the COVID-19 period, we will return to growth rates that are superior to our developed economy peers as we benefit from recovery and growth across the Asian region.

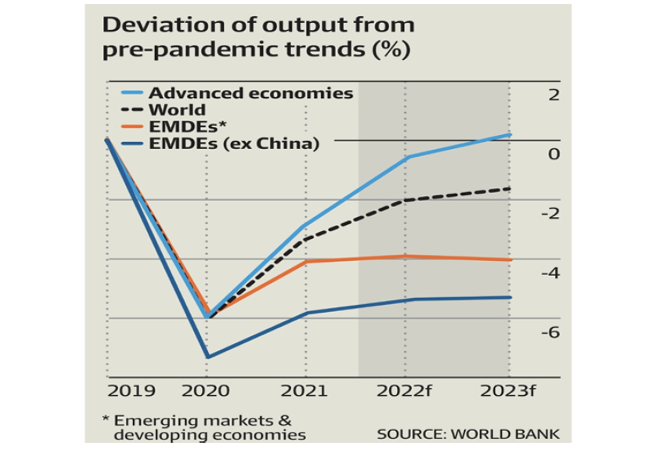

There is no doubt that COVID-19 has hit emerging economies hard and pushed their current growth profiles downwards. However, the virus headwinds will soon fade, and these parts of the world will recover and then grow strongly. The short-term World Bank forecast (refer to graph) may be too negative, particularly if COVID-19 turns from pandemic to endemic in 2022. However, it does suggest a strong bounce back post 2022.

The tangible effect on world growth is primarily due to the emergence and broadening of the middle classes, as has been occurring over the last three decades in China. Other developing and emerging economies will follow. This will supplement growth for those “developed” economies which support the free trade of goods and the flow of capital to these countries. In turn, this should provide a steady tailwind for the growth of asset prices that are attuned or leveraged to this opportunity. Australia generally, and specifically its growth asset markets, are well-positioned to benefit.

In recent years, we have observed growth in the Indian economy at double the average rates of the world. Since 2000, India’s GDP has risen by around 9% per annum. Whilst India is clearly the standout, others will follow with their growth rates somewhat determined by their political will, cultural attributes, and access to capital.

Growth across the developing world might not be as dynamic as China’s has been over the last three decades - after all, it has averaged almost 10% per annum since 1978 - but it will occur and thereby support world growth, even as many developed economies either falter or slow due to their ageing populations. By way of comparison, a country such as Italy has only grown by around 2% per annum over the last twenty years.

Having made those observations, I reiterate that the short-term outlook for markets is not so clear. Whilst investors will be rewarded (as they always have been) over the longer term, traders focused on the short term will have a difficult environment to navigate – more so if they don't perceive the nuances of Central Bank statements, understand their real policy endeavours and understand that they are no longer truly independent.

The 2022 market environment

The short-term outlook for markets and asset prices is clouded by a number of well-reported issues. Whilst known, these issues could develop in highly uncertain ways that could either support or hinder short-term prices. What could initially be perceived as a ‘white swan’ or positive event could quickly switch to a ‘black swan’ or negative event.

An example of this quandary is the milder Omicron variant, which has swamped the far more dangerous Delta. If this pattern persists, and Omicron subsequently peters out without being followed by a more dangerous variant, then this will be a strongly positive development for the world economy. In particular, the emerging world will be buoyed by a tourism and trade surge ensuring a quick recovery.

Sentiment and therefore risk markets in the developed world will be uplifted. (However, I suspect that asset prices will be constrained by the structure of monetary policy set by the major Central Banks, as explained below.)

Of course, if a new dangerous variant emerges, then activity across the world will (once again) be disrupted. The world will slow despite the predictable reintroduction of massive “developed” government support backed by monetary policy programs. 2022 would then become a rerun of the second half of 2020, and of calendar 2021. But this time, risk markets (equity, property, and corporate credit) will tire at their current elevated levels and drift lower.

Whilst COVID-19 twists, turns, and transmits, it is my view that there is a more crucial dilemma to consider, and one which the market commentariat is misinterpreting.

Clearly interest rates (particularly cash rates) have bottomed and will rise; and certainly inflationary pressures have emerged (with China’s deflationary influence declining, energy prices rising and the pandemic choking supply lines).

In spite of emerging inflation, there is little certainty regarding how the Central Banks intend to trade out of their bloated balance sheets (their bond trading policy). Central Banks are well aware that sharply rising interest rates can cause economic disruption, and even recession: therefore, rates will need to be “normalised” in an extremely delicate process that is not without risks.

In my view, normalisation of interest rates - whereby short-term rates match (at least) inflation - could be a decade away.

Serious consequences

Most market commentators accept the narrative of Central Banks without questioning their logic or consistency with recent past policy or indeed with each other's policies. For instance, while it is clear that the US Federal Reserve (Fed) will taper bond purchasing and might end it in March, that does not mean it will sell down bond holdings. The Fed may well decide to not roll its current bond holdings when they mature in the primary market. However, they will always retain the right to buy bonds in the secondary market if it determines that it is essential for economic wellbeing.

If a Central Bank stops buying bonds, it reduces the buy side pressure on the bond market. That buying needs to be replaced by “normal” market purchases by institutions and the public to stop a sharp adjustment in bond prices. Without replacement buying, bond prices will fall and bond yields will rise.

Similarly, if a Central Bank sells its bond holdings (reduces its balance sheet) more pressure is put on the bond market – and for what benefit?

Further, it is important to remember that major Central Banks (ex the Fed) – the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan – have no intention of immediately following the Fed. There is no end in sight for quantitative easing (QE) in Europe or Japan. Cash rates in these areas are still negative.

Today, the US bond market has ballooned to a record US$28 trillion – larger than the US economy. Bond yields could increase sharply in 2022 if Central Banks are not active and particularly skillful in their trading policies. If bond yields rise, then over a fairly short period (3 to 5 years), the fiscal policies of a government are affected as their debt servicing costs (interest) rise.

In passing I note that the Australian Government debt is not as large as developed world peers (measured against GDP) and the following chart shows how we have benefitted from the compression of bond yields by the intervention of the RBA and by other Central Banks.

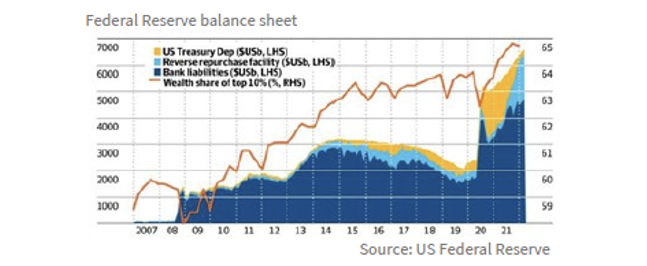

With all Governments heavily indebted, COVID-19 not yet fully dealt with, and interest rates set so low, it is unclear why the markets expect that Central Banks will actively or aggressively reduce the size of their balance sheets. In my view they won’t.

A more prudent and logical course of action for Central Banks would be to support and allow the economy to grow. In that scenario, their balance sheets would be held, but decrease as a percentage of GDP. Its actual size would stay the same. Such a course would ensure that interest rates rise slowly and methodically whilst bond yields rise at a rate that governments can afford.

No political will

Let’s be clear: the die is cast, and interest rates are moving up. But they might not go up as fast as the market anticipates. Further, with inflation leaping upwards as a result of COVID-19, real interest rates have dipped further into negative territory.

The persistence of negative real interest rates suggests that Central Banks are certainly not independent of political force or influence, despite their claims.

Indeed, the aggressive purchasing of government debt has made Central Banks the largest single owners (or creditors) of most western governments. Therefore, how can they be truly independent?

The political will of democratic western governments has been tested by COVID-19 as parts of the world (particularly Europe) continue to deal with the financial aftershocks of the GFC.

The political cycle with its regular flow of elections continues to feed populist agendas, with little appetite to reform or to restructure economies for the better. Reflecting on this, recessions generally occur when Central Banks aggressively increase short-term interest rates to smother inflation due to excess growth. No incumbent government wants to govern a country into recession, and no central banker wants to go down in history as either the architect of an economic meltdown or the devastation of their own balance sheet.

With mid-term elections in the US (in November), and elections in Europe (France, Hungary, Sweden, Ireland) and Australia (by end May), there is no political will anywhere in the western world to make necessary or hard decisions.

This supports my contention (which will become increasingly obvious in 2022) that Central Banks have a lot to lose by lifting rates too quickly. A globally coordinated response (as has recently been suggested by the Chinese Administration) is required as we attempt a normalisation of interest rates. “Let’s wait and see” will be the most used term by Central Bankers during 2022.

What does this mean for investors?

The above scenario is moderately positive for risk assets, and moderately negative for bonds.

There may be arguments (for higher asset prices) based on human greed and gullibility or supported by historical observations of excessive exuberance. However, the hope of a continuing raging bull market for equities, in the style of the recovery from the March 2020 lows, is too optimistic.

However, the current environment, after (and continuing with) a sustained period of zero bond interest rates, negative real rates, and QE across the world, is unlike anything seen in the last century. A lot of good news and expectation of recovery is already factored into risk markets.

The policy settings, from this point, will be implemented and adjusted to support sustainable growth rather than hinder it.

For example, in my opinion, it is likely that regulators (under government influence and indeed common sense) will restrict credit to segments of the economy that are overheating or creating social dislocation. In Australia, this will be seen in the residential property market.

Given the solid outlook and projected slow adjustments to interest rates, my tactical view for asset allocation is to continue to be underweight low-risk assets and slightly overweight riskier growth assets like shares and property.

It is interesting to note from the table below that higher risk growth assets generally present with a much superior cash yield than low risk assets. Therefore, if growth is secure over the longer term, it remains hard to justify any significant weighting to low risk and low yield assets. A good and broad spread of yielding risk assets presents a sensible portfolio response for investors who require regular income.

Holding some cash, perhaps between 5% and 15% (depending on personal circumstances), is always sensible in periods of heightened uncertainty. Cash operates as a safely cushion – it would only start to become attractive if cash deposit rates were to rise far higher than expected

As the following table of current market expectations suggests, interest rates will rise steadily across the world. However, they are likely to remain below inflation, and the purchasing power of passive assets will be continually diluted.

Aggressive interest rate rises will not occur in the US (they may rise by 1% to 1.5% over the next 18 months).

Indeed, the ability of the Fed to move rates higher will be checked by its focus on growth, support for the political imperative, and because neither Europe nor Japan will follow suit.

Cash interest rates will probably be 2% to 3% below inflation readings at the end of 2022. Even today, we can see that 10-year German bunds (sovereign debt) are yet to move back to a positive yield (yes – above a zero yield), although it will surely happen in 2022.

My conclusion

I am neither negative nor positive in looking at the world’s risk assets or markets for 2022. I believe that good quality assets - whether they be equities, property, or corporate debt - will continue to do relatively well in 2022. More importantly, they will do particularly well over the rest of this decade.

There is no reason to expect that every year in a longer investment time frame will produce above average returns. In my view, 2022 will be a positive but low returning year as interest rates slowly begin to lift. The current market turmoil will pass, a new base set and positive returns recommence.

Companies or assets that generate solid cash flows and distribute or reinvest them in a sensible manner will continue to prosper. In 2022, cash received from income (as opposed to capital gain) may well make up the bulk of investment returns.

Average or poor quality assets, measured by cash generation and return on equity measures, will continue to be challenged. Slowly rising interest rates, inflationary and cost pressures, will pressure weaker assets.

As for cash, bonds, and low yielding fixed income assets, I would restrict exposure to moderately low levels. The holders of these assets are faced with a real dilemma in their portfolios, particularly when they consider the impact of inflation.

Investors would do well to sit back on their good investments and turn down the noise from the omnipresent commentators who front aggressive trading enterprises - for it is the traders that have real conundrums to deal with in 2022.

Those conundrums will be determined by Central Bankers, who will pivot when necessary and are no longer truly independent but who will support economic activity rather than drive an economy into recession.

Never miss an insight

Enjoy this wire? Hit the ‘like’ button to let us know. Stay up to date with my content by hitting the ‘follow’ button below and you’ll be notified every time I post a wire.

Not already a Livewire member? Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.