Central banks in retreat

A masterly retreat can itself be a victory, or so penned American author Norman Peale. And key global central banks have spent the past two months in retreat, signalling pauses or delays to both rate rises and balance sheet unwinds. This has underpinned a strong start to equity markets in 2019.

“Part of the happiness of life consists not in fighting battles but avoiding them. A masterly retreat is in itself a victory.”

Norman Vincent Peale - American Author and Clergyman

Of course, market sentiment has also been helped by an improving tone in the US-China trade spat, culminating in President Trump delaying the 1 March deadline for increasing tariffs. Brexit negotiations continue to break new ground ahead of the 29 March deadline, with the risk of a ‘no-deal’ exit falling and the likelihood of a delayed departure rising. Some stabilisation in data—a rebound in China’s exports and credit growth, still strong US jobs and a tepid rise in European business conditions—has also helped.

But most important is the new ‘patient’ tone from the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and the likelihood that monetary policy tightening is ‘on pause’ for at least the next six months. It is this that has calmed markets and reversed the tightening in financial conditions that catalysed December’s collapse in risk. Yet the Fed’s ‘retreat’, at least initially, has been made possible by inflation receding. Globally, inflation has fallen short of most central bank forecasts (despite very tight jobs markets). This ‘shortfall’ in inflation is something we identified back in September 2018.

This month, we take a look at the dramatic shift in expectations around central bank tightening in the year ahead. What started with the Fed has spread like wildfire to the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of Canada (BoC), the Bank of England (BoE), the Bank of Japan (BoJ) and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). Prospects for a sharp move higher in yields have been forestalled for now, while the outlook for currencies has also been altered.

We have made no tactical changes to our asset allocation this month. Our 2019 outlook embodied expectations that central banks would pause and a further escalation in geo-political risks could be avoided. Thus, we remain cautiously engaged with risk, while ensuring diversification through defensive government bonds and alternative assets. It is true that the rally in equities has reduced the market’s attractiveness. But the key issue for clients is whether the global pause from central banks—and renewed stimulus in China—has elongated the latter stages of this macro cycle. We think it has.

Shifting central bank expectations have calmed markets

The US Federal Reserve — from hikes to on hold

“Many participants commented that upward pressures on inflation appeared to be more muted than they appeared to be last year.” - January 2019 Fed meeting.

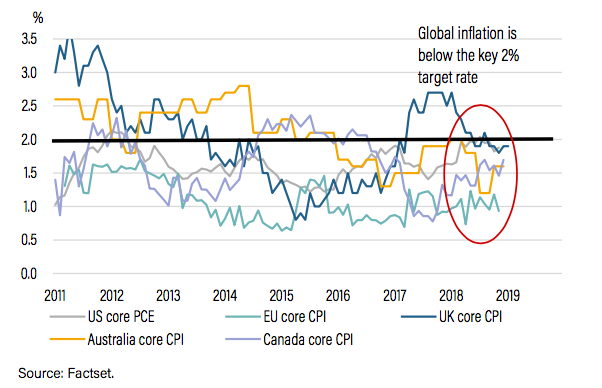

Having risen from 1.4% in mid-2017 to 2.0% in mid-2018, the Fed’s preferred inflation measure, core personal consumption expenditure (PCE), has now stalled below 2% (the Fed’s target) for several months. Looking ahead, more trend-like US growth (and lower oil prices), despite falling unemployment, also suggest less inflation pressure.

At the start of December 2018, the Fed was planning to hike three times in 2019. It trimmed that to two at its mid-December meeting. But after its late January meeting, a more ‘patient’ wait-and-see approach was signalled. UBS shifted its view to a single Fed hike in September this year. In contrast, Société Générale is forecasting no hikes in 2019 and rate cuts in 2020.

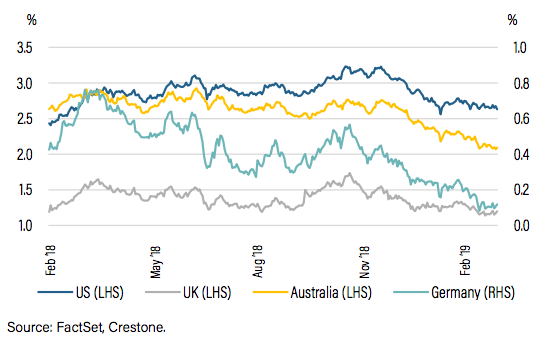

Financial markets are pricing no further action from the Fed this year, while also flirting with an easing of rates (from 2.5%) and an end to balance sheet reduction later in the year. Reflecting this, US 10-year government bond yields have fallen from 3.19% in November to 2.67% currently.

The European Central Bank — shifting to more stimulus?

“The risks surrounding the euro area growth outlook have moved to the downside.” - Mario Draghi, President of ECB, 24 January 2019.

The ECB ended its quantitative easing (QE), or bond buying, at the end of 2018. Forecasts for stronger growth and rising inflation saw the ECB signal rate hikes (from -0.4%) starting in Q4 2019. But European core inflation has failed to lift, being stuck at 1% (against a 2% target) for the past six years. Like the US, this has occurred against a backdrop of a tightening jobs market.

The ECB has not changed its forecasts but, for the first time at its January meeting, it has flagged downside risks. Financial markets have shifted expectations for the ECB’s first hike to H1 2020, while UBS and CBA have delayed it until Q1 and Q4 2020 respectively. Given the sharp slowing in European growth during H2 2018, there is also speculation the ECB may announce new stimulus measures. Government bonds in Germany have fallen from 0.56% in October to just 0.14% currently.

Global inflation has fallen short of central bank forecasts

The Bank of England — a more dovish tone

We are “bit-part players in a much bigger drama”, shifting dovish on Brexit uncertainty and a slower global backdrop. - Mark Carney, Governor of the BoE, 7 February 2019.

The BoE hiked rates in August last year on the back of a growth rebound in Q2 and a tightening jobs market, taking the policy rate from 0.50% to 0.75%. However, according to CBA, “the economy has slowed because of Brexit and the global economic slowdown”. Inflation has retraced from 2.7% in August to 1.8% in January, below the BoE target for the first time in two years.

At its February meeting, the BoE cut its growth forecasts. It also confirmed its asset purchase reinvestment facility will continue buying government bonds. While still focused on a post-Brexit growth rebound and ‘gradual’ future tightening, it has nonetheless stepped back from its more upbeat tone. CBA has delayed its 2019 hike expectations until 2020. UK 10-year government bonds have fallen from 1.74% in October to 1.20% currently.

Other global central banks

Elsewhere, a range of other central banks have softened their policy tightening, mostly on the back of lower-than-forecast inflation. In late January, the BoJ trimmed its inflation outlook by a notable 0.5%, and UBS sees the 0% 10-year government bond yield target unchanged until 2020. Société Générale, however, forecasts no change until mid-2021. In December, the BoC turned dovish, signalling a “clearly more uncertain” outlook.

In emerging markets, China’s central bank is deep in an easing program to combat the negative impact of the US-China trade war. Both bank reserve requirements and small business tax rates have been cut. India’s central bank surprised with a rate cut in early February due to lower inflation.

Reserve Bank of Australia — volte-face!

“Looking forward, there are scenarios where the next move in the cash rate is up and other scenarios where it is down.” - Philip Lowe, Governor of the RBA, 6 February 2019.

As recently as November, the RBA materially upgraded its outlook, seemingly moments before conditions turned weaker. Subsequently, the RBA cut its inflation and growth outlook in its February update. The faster-than-expected correction in housing, including tighter credit conditions to small and medium businesses, was key to the shift away from its prior tightening bias.

The RBA argues the strength of jobs growth and low unemployment will be a strong defence against the need to cut rates from 1.5%. However, having been positioned for rate hikes at the end of 2019, financial markets have now fully priced an RBA rate cut by the end of this year, with another cut in 2020.

The RBA has clearly shifted to a more dovish stance. A further material weakening in the housing sector in H1 2019 remains the most likely catalyst to drive it to further cut rates from its already record low level. Australian 10-year government bond yields have fallen from 2.76% in November to 2.09% currently—they have also significantly outperformed their global peers.

Bond yields fall as policy tightening expectations are eased

Implications for fixed income markets

Although global growth has been above trend for the past couple of years, inflation has only managed to meander toward central bank targets and, in many cases, has fallen short. The interaction between clearly tightening jobs markets and so-called structural disinflation forces that limit the modern rise in inflation (such as globalisation and automation) remains uncertain.

However, with global activity now retracing to a more trend-like pace and inflation proving benign, the urgency for central banks to normalise policy (by both lifting rates and unwinding balance sheets) has eased. The recent downdraft in global growth could also gather momentum. Market unfriendly outcomes in US-China trade and Brexit negotiations are still possible.

But it is more than likely that a stabilisation of growth through 2019 and a further tightening in jobs markets will provide central banks with scope to re-embark on normalising policy. Yet it seems unlikely that such an environment will arrive before late this year at the very earliest.

With bond yields having now rallied 40-60 basis points (bps) since early Q4 2018 (see previous chart), there are a number of implications for investors:

- Central banks now seem likely to be less active during 2019, suggesting fears about duration risks have somewhat abated for now. However, a further shift lower in yields also appears less likely from here.

- A return to a higher-yield environment has likely been delayed, and yields could trade in a narrower range ahead. A delayed central bank balance sheet unwind will also maintain downward pressure on yields.

- While high-grade bonds retain their defensive portfolio characteristics, the sharp rally in yields has reduced their risk-return benefit.

- A persistently low-yield environment is likely to encourage fixed income focused investors to chase yield, moving to higher risk credit.

Implications for the Australian dollar and other currencies

Significant event risk can still lead to sharp currency adjustments (with the British pound a likely candidate in 2019). However, steadier central bank policy in 2019 should typically portend a steadier exchange rate environment:

- With the Fed no longer leading the charge on rate rises (as has been the case in recent years), the US dollar may prove more stable in 2019 and possibly trend lower (particularly if global growth stabilises ahead).

- For emerging markets, a more stable US dollar will allow some stabilisation and recovery in both exchange rates and capital inflows.

- For the Japanese yen, the likelihood the BoJ will remain on hold will leave the currency to ebb strong during risk-off periods and vice versa.

- For the euro, the shift from tightening to ‘on hold’ with the risk of further stimulus suggests the prior market forecast for a strong rebound in the euro is less likely. Unless growth recovers, the euro may weaken.

The Australian dollar remains exposed to significant cross-currents. The resilience of commodity prices and renewed China stimulus suggest it should be closer to USD 0.80, while record low local interest rates with risk of further rate cuts suggest it should be closer to USD 0.60. With the Australian dollar currently sitting around the middle of this range—and also quite near its 35-year average since free floating—strong directional calls are more difficult.

Over the short term, we continue to see the risks to the downside for the Australian dollar, potentially with a move to USD 0.70 or even to USD 0.68/69. This reflects the expectation that it will be some time before global data strengthens and supports the currency and political uncertainty is elevated into mid-year. Further, the risks to domestic growth and rates remain firmly to the downside, particularly given Australia’s highly-leveraged consumer.

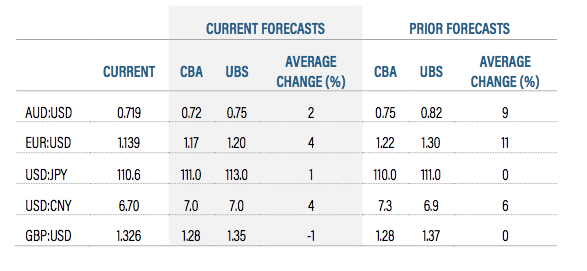

However, the resilience of the economy, the potential for rate cuts to support activity, the strength of Australia’s fiscal position and its AAA credit rating argue against a materially more bearish stance. As the table below reveals, even after the recent significant revisions, both UBS and CBA expect the Australian dollar to be unchanged or higher by the end of 2019.

Currency forecasts now suggest 2019 may embody less significant moves in exchange rates.

Recent changes to currency forecasts for end-2019

Never miss an update

Stay up to date with the latest news from Crestone Wealth Management by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

Crestone Wealth Management provides wealth advice and portfolio management services to high-net-worth clients and family offices, not-for-profit organisations and financial institutions. Find out more

1 contributor mentioned