Central banks will go too far

In tightening cycles, central banks typically raise rates until something breaks. We have had a few candidates in recent weeks, Credit Suisse, Argentina and most surprisingly the entire UK pension market.

I have an emerging market blowup and a random investment bank that didn’t understand the risks on my “what to watch in case it blows up” bingo card, but the UK pension market was not one that I was expecting. Some timely intervention by the UK central bank, and a government backflip have taken the sting out of that one.

The real question is:

What markets should you be watching for something to break?

Inflation path

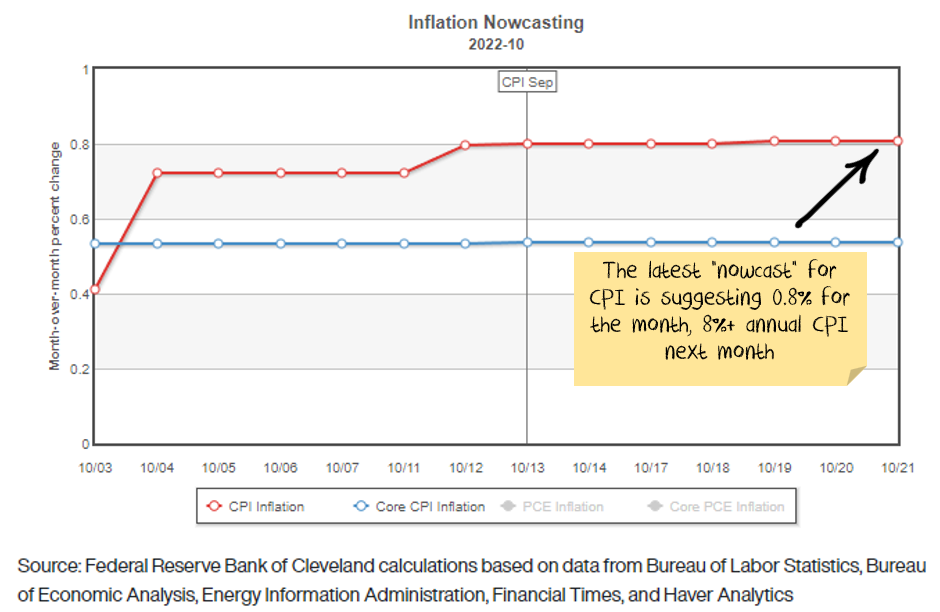

To start, I’m going to assume that the Cleveland Fed “nowcast” US inflation for October is about right:

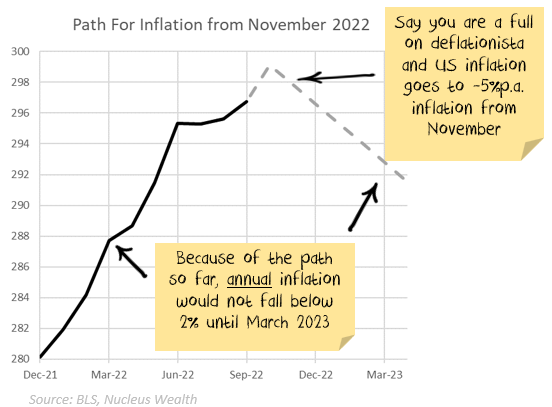

The big issue, as I see it, is that the path US inflation has taken to date means that annualised inflation is going to stay high for at least six months. Even if the US went into a depression starting November, with monthly inflation at say -5% per annum (so deflation), annual inflation would stay high until March:

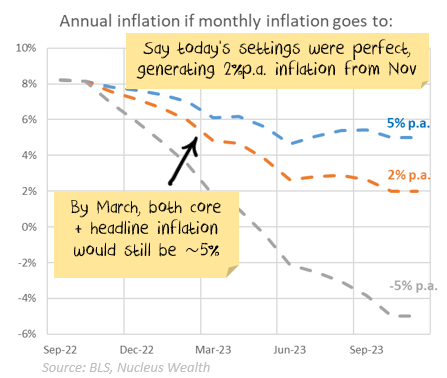

This is going to leave the US central bank in an unenviable position. Use the above example where the central bank has clearly gone too far:

- At the March meeting the US central bank would have seen four months of deflation at a -5% annualised rate

- But annual inflation would still be 3.5% at the headline, 2.8% for core inflation

- So, even with a dire outcome for inflation, it would be very hard for the US central bank to back-track

- More likely they would pause for several months, worsening the problem before having the cover to pivot

Say you were more circumspect and thought that current interest rate settings were perfect. Say inflation fell immediately to 0.17% per month (2% per year). By March, annual inflation would still be around 5%, which means the Fed is probably still raising rates beyond what is required.

Net effect: if the US central bank already has interest rates too high, they are unlikely to have annual inflation low enough to start lowering rates until the middle of next year. The risk of policy error is high.

Which central bank should we fear the most?

The US central bank is the default answer. Policymakers have promised to squash inflation, even if it causes a recession. Rates have higher to go, and the charts above show you that headline inflation will stay high even if deflation takes hold. Wages growth is still strong. And most long-term bond markets around the world are taking their lead from the US.

The UK central bank has made a late entry into this category. The UK has high inflation, high wage growth, a big current account deficit and a budget deficit. Into the teeth of this, the UK government suggested an extreme form of tax cuts and trickle-down economics. After a market revolt, and some concerning liquidity issues in the long-term government bond market, the UK government backflipped. The lesson? Rising interest rates lowers the margin for error. Financial shocks can come from unexpected places.

Hyman Minsky is an economist who is most famous for his risk framework. Basically, he posits that when risks are low for a long time, individuals get too used to low risk and start to use derivatives, debt and other forms of leverage to increase the risk and returns. When the stability ends, the financial shock is much larger because of the amount of leverage in the system. This is highlighted by the long-term bond market in the UK which suffered big liquidity problems as rates spiked, requiring a central bank intervention.

In a way, the problems with the UK bond market and government spending is a classic emerging market shock. The punchline is that the UK is not an emerging market.

The European central bank has its own risks. Despite eye-wateringly high energy prices, which are dragging on consumer demand, and a likely recession, they have been raising rates. At the same time, a number of countries like Italy and Spain that had problems with high debt and low growth after the financial crisis still have high debt and low growth. A rising interest rate may expose further problems.

The Chinese central bank has the opposite problem to the rest of the world. Inflation is low and falling. Interest rates are edging down rather than up. Lockdowns are constraining supply, but a bigger issue is the slow-motion crash in the property sector. Can the Chinese central bank manage the above? At the same time, the impossible trinity is breaking down. Inflation is low owing to terrible domestic demand but sinking currency and capital flight threaten any easing. Fiscal policy has been the answer so far but not enough. There is a danger of capital flight and the Yuan has been weak.

A rising US dollar puts pressure on emerging markets as (a) emerging market debt is often US dollar denominated (b) import prices rise and (c) many emerging markets are reliant on commodities that also suffer under a high US dollar. Adding to the problem, a weak Chinese Yuan means that exports to China will suffer while China’s own exports will be more competitive.

What are the likely scenarios?

- Central banks cool inflation without breaking anything too big. Only slow easing. Result: Moderate global recession.

- Rising rates trigger rolling sovereign debt crises or other meltdowns. If the UK is Bear Stearns, who is the Lehman Brothers? Result: Deep global recession.

If the second scenario occurs, how big could it get? First, a deepish recession is likely to result in a deflationary shock. The question then is whether the deflationary shock is followed by:

- Austerity as debt crises rock governments

- Central banks pivot to printing and governments start spending regardless of the fiscal situation

If the first, then we will have a re-run of the 2010s. If the second, inflation (particularly in energy) could well be back with a vengeance a year or two after. But that is a step ahead of the current problem. Right now we want to know which markets we should be watching.

Where are the vulnerabilities?

If central banks go too far, then something will break. There are a range of different candidates that are vying for the opportunity to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back:

US Corporate Lending:

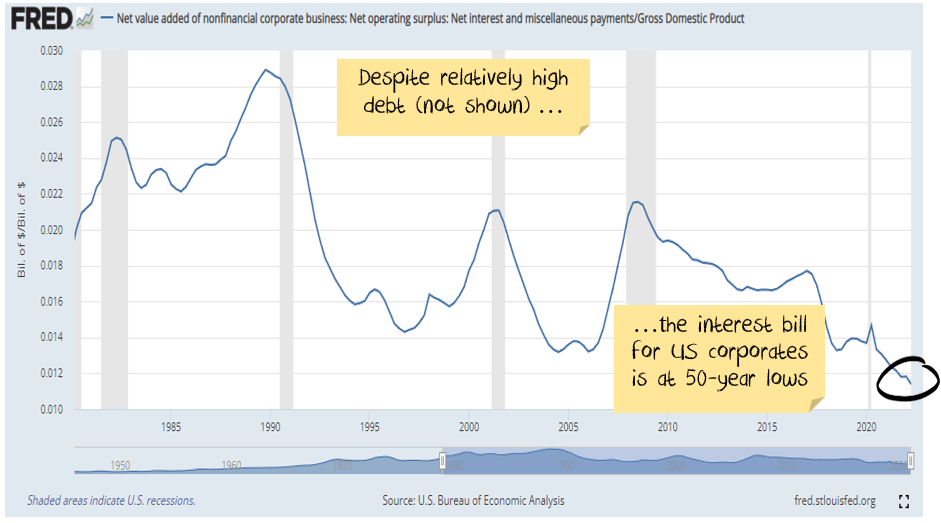

Over-leveraged corporates are often to blame when central banks break something. But probably not this time.

Debt levels are relatively high. Interest burdens however are not, due to low interest rates in recent years. This will change, but the average loan term for corporates is 3-4 years and so it will take a considerable period of time before this becomes a widespread issue.

There will of course be individual companies that run into trouble. And the number of these will increase. But, there do not seem to be endemic overleveraging issues.

It is more likely that something else breaks before US corporates do.

US Consumer Lending:

Over-leveraged consumers were the key factor that broke during the financial crisis in 2007. But, US consumers broadly delevered following that episode and don’t have excessive levels of debt. Additionally, with most mortgages fixed for 30 years at current low interest rates, the debt service costs are low for many.

US Asset Markets:

The stock market has been increasing its correlation as a factor in consumer confidence and consumption. In 2000, the recession was led by the bursting of the Tech bubble. Potentially that could happen this time. Falling house prices will probably exacerbate the issue.

US Inventory glut:

We are now on the other side of the inventory cycle. Many companies have excess inventory as a hangover from the supply chain problems which led to hoarding. With supply chain issues largely solved, it is likely that company earnings will be hit as the inventory cycle unwinds.

The thing is, the unwinding of inventories is part of the ordinary business cycle. It is not typically an end-of-cycle event. i.e. inventory destocking is likely to be a drag on growth, but unlikely to be the catalyst for a crisis.

European politics:

There is a lot that can go wrong in Europe. Russian sanctions distorting food and energy prices add an extra layer of risk to everything. A cold winter would see a further energy shock on top of an already strained system.

Politics is another major risk. The imbalances that sparked the European Debt Crisis in 2009 have never really gone away. They have just been hidden by negative interest rates and lots of money printing. Sovereign debt issues could reappear. Arguably, they already have in the UK through the whole Truss budget debacle. Parties with relatively extreme policies are attracting more support. These parties do tend to reduce their extreme policies once in power (see Five Star in Italy and Syriza in Greece), but then get voted out. Presumably, because voters want something more extreme. Next on the clock? Brothers of Italy.

European banks:

The problems with Credit Suisse over the last few weeks are a reminder:

- Bank returns are low, leaving not much room for error

- Rising rates will cause unexpected problems

- A liquidity flood made every investor a genius, now the tide is going out.

My expectation is that investment banks that run into trouble will probably get bailed out. But only probably. There are risks.

Chinese imbalances:

China is running into a buzzsaw. Economically.

- A huge boom in goods during COVID is just finishing, so the industrial sector will be weak.

- Property starts are down 65% peak to trough – and showing no signs of slowing.

- As an indicator of how large the Chinese property building boom was, starts could fall another 30% and still only be at the average level we see in other economies.

- Property is such a huge part of the Chinese economy that the pain is spreading to other sectors. There are banking risks, not least from the overleveraged property developers.

- Zero-COVID policies have led to continued weak consumer demand.

- Deflation and falling interest rates are in stark contrast to the rest of the world and so the currency is weak

Vulnerabilities abound. Will any of them come to fruition?

Emerging Markets:

A strong USD is often the precursor to an emerging markets debt crisis. The Chinese currency falling is problematic for emerging markets in a different way. Both have been occurring.

Australian Consumer Debt:

Could the Australian consumer spark a debt crisis? Sure. When you mix together:

- Housing expensive, but falling in price

- High household debt levels

- More variable mortgage rates than elsewhere

- Low wage growth

- An electricity shock in Eastern states

then you have all the recipe for a crisis.

What will break first?

It is hard to tell. My best guess is a continued slow-motion crash in China, followed by a broader emerging markets crisis or capitulation of the Australian consumer. But, as the UK long-term bond market and Credit Suisse showed us, there are vulnerabilities in unexpected places.

Maybe we muddle through with swift rescues for failing sectors while central banks guide us into a feathery soft landing. But I doubt that.