China’s deep structural problems with no easy solutions in sight

Themes preoccupy the investment industry. Inflation and rising interest rates have dominated industry thinking over the past two years and continue to remain front of mind.

Recently, another iceberg has appeared to give us more to mull over — China’s struggling economy.

China’s economic trajectory matters to the world and is especially significant for Australia as the prosperity of our natural resources companies, education providers, tourism industry, and wine producers, amongst many others, is bound to the country’s fortunes.

Last year, China accounted for 64% of US chipmaker Qualcomm’s sales, and 37% of Mercedes-Benz’s retail car sales were made there.(1)

A China that buys less from the world, or invests less globally, will be an economic handbrake.

As China came out of COVID-related restrictions last year, there were expectations its economy would roar back to life. That’s not how things have panned out.

To be clear, some parts of its economy did rebound — domestic tourism, hospitality, and retail services — on the back of the release of pent-up demand.

However, soft durable goods consumption trends, weak private-sector investment rates, and households emphasising saving, suggests that people and companies are battening down the hatches.

More recently, one of the country’s largest property developers, Country Garden, has been battling a debt crisis, a symptom of larger problems.

China has one of the world’s largest homeownership rates with official data showing it hitting 90% in 2020(2). Moreover, property is estimated to account for around 70% of Chinese household wealth(3) and the property sector and related industries make up around third of its economic output. That includes houses, rental and brokering services; industries producing white goods that go into apartments; and construction materials.

However, the price rise music has stopped and there have been stories of ‘mortgage strikes’ with borrowers refusing to make payments on properties amid falling prices.

Add to this mix massive debts racked up by local governments that, up to now, have used land sales to raise revenue and it’s a disturbing picture.

It would be easy to get caught up in endless recent economic statistics but doing so runs the risk of losing sight of profound structural issues facing the country.

End of an economic model?

The decades-long model of pushing the economy upward with another shot of fixed asset investment has seemingly reached its limits. The marginal utility of the next new highway, airport, railway, or city is declining, and policymakers recognise this, and that’s why Beijing has not announced another massive old-school stimulus program.

What to do about this, so that China doesn’t fall into the ‘middle-income trap,’ is historically important.

The middle-income trap describes a situation where a middle-income country can no longer compete internationally in labour-intensive industries because wages are relatively too high, but it also cannot compete in higher value-added activities on a broad enough scale because productivity is relatively too low. Consequently, there are fewer avenues for further growth. Arguably, this is now China’s situation.

The quote, “Demography is destiny” is widely known and even if an overstatement, demography is very important to the development of economies and countries.

Here are a few especially noteworthy figures relating to China’s demographic situation:

- The Seventh National Population Census(4), published in 2021, revealed that only twelve million babies were born in 2020, the fewest newborns since the horrific Great Leap Forward related famine of 1961.(5)

- China’s working-age population, aged 16-59, is contracting, falling by 40 million workers since 2010 to less than 900 million today.(6)

- China recorded a net increase of just 480,000 people in 2021, the lowest ever official rate.(7)

- The Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences team predicted an annual average population decline of 1.1% after 2021, pushing China's population down to 587 million in 2100, less than half of what it is today.(8)

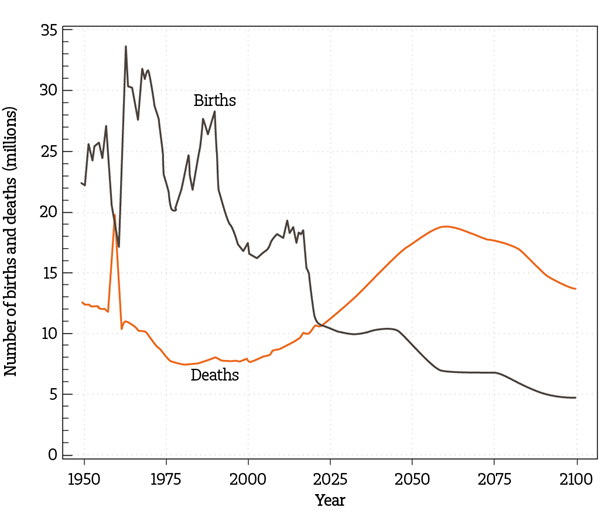

As it is, China’s population growth may reach a tipping point soon (see chart) where the mortality rate outpaces the birth rate, and the population begins to decline. No wonder it’s now being said of China that the country is going to become old before it becomes rich.

Deaths predicted to exceed births soon

Annual number of death and births in China

Source: United Nations World Population Prospects 2022

The leadership emphasised that “proactively responding to the aging population directly relates to the country’s development and people’s well-being,” and is necessary to “safeguard national security and social stability.”(9)

But policy changes are unlikely to easily solve China’s demographic problem. The easing of the one child policy to allow two children per couple in 2015 did not translate to an increase in births, and so it’s uncertain that increasing the limit to three children will have much impact.

China’s population has reached a level of education and income where having larger families has lost its appeal. That is because there are many other factors keeping the birth rate and fertility down, some of which are trends seen in many industrialised and newly industrialised countries.

Increased participation of women in the workplace and changing attitudes toward marriage means people are less inclined to have children. Additionally, the rising cost of living and changing expectations toward quality of life and lifestyles means that people are less willing – and capable – of taking on childrearing responsibilities.

These are profound structural issues any government would struggle to address. It’s not impossible that China could experience some of what Japan has endured since the bursting of its property and asset bubble more than three decades ago.

All sorts of criticisms have been fired at Japanese policymakers but a lot of that seems overdone given the aging of the country’s population and drop-off in births explain much of what’s transpired.

There is only so much governments can do to turnaround structural demographic trends.

China equity exposure in portfolios

Ironically though, potential returns from Chinese shares may be more promising now than in the years when the country’s economy was growing at thumping rates. Large state-owned enterprises, which are by-and-large inaccessible to investors, drove much of the growth in the go-go years. Now, however, small-to-medium sized listed companies are much more to the fore enabling investors to participate in their growth.

Consistent with this, one of the ways we are providing portfolios with exposure to Chinese shares is through investments in companies listed on the Shenzhen Composite Index. This index provides greater access to sectors that, we believe, will benefit from government policy favouring small-to-medium sized enterprises over big companies.

Our positioning in developed country share markets have been fine-tuned to lean towards ‘quality companies’, that is, companies with strong records of profitability and cash flow dependability. We believe that share market valuations currently capitalise levels of optimism that are at odds with ambiguous business conditions, and ‘quality companies’ are better placed to navigate uncertainty.

Role of skill-based strategies

It is also times like now that the diversifying character of our alternative investments become especially valuable.

The skill-based liquid trading strategies in our toolkit can go short assets (benefit from a fall in asset values), as well as long. Freeing managers from the long-only constraint empowers them to act more comprehensively on their views than is possible with long-only investing.

We also know that the last 30 years have been unusually favourable to long-only investors in equities and bonds, and it is plausible the next decade may be bumpier. This means that identifying global macro and trend following strategies that can make money from being short equities and short bonds at the right time, could potentially benefit our diversified portfolios.

Putting our investment beliefs into action

The skill-based strategies, as well as the derivatives strategy applied to our China shares’ exposure, are expressions of our five investment beliefs in action.

Great culture is the foundation for great investing

A culture that fosters debate; encourages fearless enquiry; values humility; and which rests on trust and collaboration is the basis of great investing.

Consistent with this, we embrace change, and new ways of thinking and investing recognising that what has been effective in the past, may be less so into the future.

Active management adds value

There are many factors that may lead to current market pricing not accurately reflecting the value of an asset to a long-term investor like us. This may include behavioural biases like overconfidence and herding (following the crowd), availability and access to information, and the fact that deep research and analysis can reveal the ‘intrinsic value’ of an asset which has been overlooked by other investors.

It’s these market inefficiencies that present opportunities for skilled active management to add value, delivering stronger long-term returns than would be possible by investing in a passive manner.

Skilful diversification delivers over the long-term

Skilfully constructed multi-manager portfolios made up of a wide breadth of asset classes, many assets within asset classes, risks, investment styles, and investments across many geographies maximises the odds of achieving strong long-term returns while managing risk.

Successful investing relies not just on strong performance in rising markets but also on preserving investors’ capital in hostile markets. The combination of skilful diversification and active management is one of the best ways of achieving these dual objectives.

Intelligent risk taking is a must

It’s understood that some risks must be taken to achieve return objectives. However, not all risks are equal.

Our role as active managers is to assess the range of possible market outcomes and position portfolios so that they maximise the chance of meeting clients’ return expectations while minimising exposure to risks unsupported by high conviction.

The long-term matters but we remain agile

Deeply held investment convictions, sound judgments gained from navigating multiple market cycles, and structures and incentives that reward patience and perseverance, support our long-term focus.

At the same time, we are very mindful of occasions when market events can, if overlooked, undermine returns. Our risk-aware investment approach alerts us to possible threats and position portfolios to weather difficult market conditions.

Learn more

MLC Asset Management applies its knowledge and experience, with the aim of delivering the best possible investment results for institutional and retail clients in Australia and globally. For more information, please visit our website.

1 topic