Fed's "Dirty Harry Moment"

The best way I can think to describe what happened on Friday was that this was US Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell's "Dirty Harry moment".

Whatever guns the hedge fund bears were bringing to the COVID-19 fight, the dithering and historically market-unfriendly Fed chair has clearly committed himself to out-muscling them. (This was the guy who when he first cut rates by 50bps in early March told the world that the Fed was not going to do any QE.)

Friday's decision was tantamount to Powell staring down the shorts and declaring, "You've got to ask yourself one question: 'Do I feel lucky?' Well, do ya, punk?"

The audacity of the Fed's move was breathtaking. While we were convinced in late February that the inability of financial markets to price global pandemic risks meant that we would get the mother of all liquidity/solvency crises that would in turn necessitate unrestricted liquidity support and quantitative easing from central banks, which was a novel view at the time, we never imagined the Fed would go as far as to start buying junk bonds.

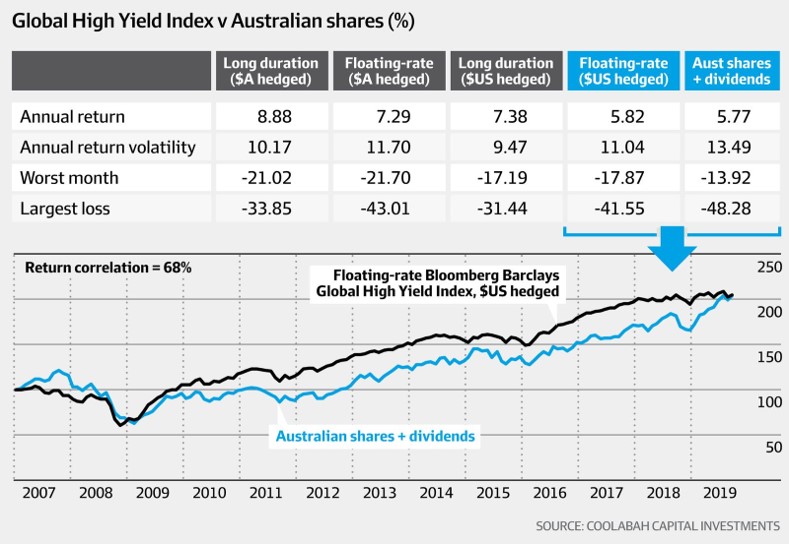

Many high-yield or sub-investment-grade bonds (ie, with credit ratings less than the minimum "BBB" investment-grade threshold) are basically equities with inferior liquidity, as we have shown before. The Bloomberg Barclays Global High Yield Bond Index has very similar long-term volatility and worst losses to the Aussie equities index (see table/chart below).

That makes sense: this is typically debt issued by smaller businesses that are not publicly listed, or the junior-ranking debt of bigger firms. That is to say, it is debt that is similar to the equity of large listed companies. And the data highlighted below bears that out.

The Fed is now arguably the biggest asset manager in the world (with over US$6 trillion in AUM) with one ace up its sleeve: it has never-ending capital through its unlimited ability to print money and can never, therefore, really lose. If the market wants to try and bet against the Fed, the Fed will simply buy it--and I mean all of it. Hence the aphorism, "Don't fight the Fed!"

There is some quasi-logic rationalising the Fed's decision. In the primary and secondary bond markets, it will only buy high-yield bonds with BB ratings that were previously rated investment-grade (BBB and higher) as at March 22 (ie, it will not buy bonds with ratings less than BB or which were junk before March 22). The idea is that the Fed will support "fallen angels" that have been downgraded to junk, or below BBB, as a result of the great virus crisis (GVC).

The problem with this defence is that the Fed is also going to be directly buying high-yield ETFs, which include many bonds rated below BB (and all of which were junk before the GVC), although the Fed argues that the "preponderance" of its ETF purchases will be focussed on investment-grade ETFs.

I am not sure anyone knows what the definition of "preponderance" is. It could be 60%, 70% or 80%, and is presumably going to be left to the Fed's discretion.

The mitigants are that the Fed can only buy up to a maximum of 10% of any bond issue and 20% of any given ETF, it cannot buy ETFs at a price above NAV, and the program is slated to end in September this year. One would have to think that the many folks worried about high yield defaults and downgrades will use the Fed's purchases as a liquidity point.

It is also worth noting that the Fed's chair was a partner of the Carlyle Group, a leveraged buyout firm, between 1997 and 2005, and there is no doubt that this decision will help his private equity buddies who rely on the high-yield market to leverage their investments. The illiquidity and soaring cost of this debt combined with plummeting corporate earnings risked blowing-up many of their portfolios...

In conjunction with our forecast for the peak in US and Australian infections to arrive in early-to-mid April, which has come to pass, this is clearly a very positive development for short-term risk-taking and sentiment.

We nevertheless remain concerned about downgrades of BBB rated corporate bonds to junk and rising default risks in the high-yield market and amongst mid-cap companies that are neither too-big-to-fail nor too-small-to-matter. We have consistently warned about the elevated risks embedded in corporate high-yield bonds over the last 12 months, which during the GVC have most vividly blown-up in the ASX listed investment trust (LIT) market. We sold our two senior-ranking corporate bond exposures in January.

3 topics