FINALLY Australia gets interesting

Global Macro

January 1996. My wife was 8 months pregnant with our first child. I was a proprietary trader at Bankers Trust (had been since 1991), meaning I took macro views on interest rates and currencies. Indeed, very similar to what I do now, but with the bank’s capital rather than investors’ capital. And I had just come off a frustrating performance year – 1995.

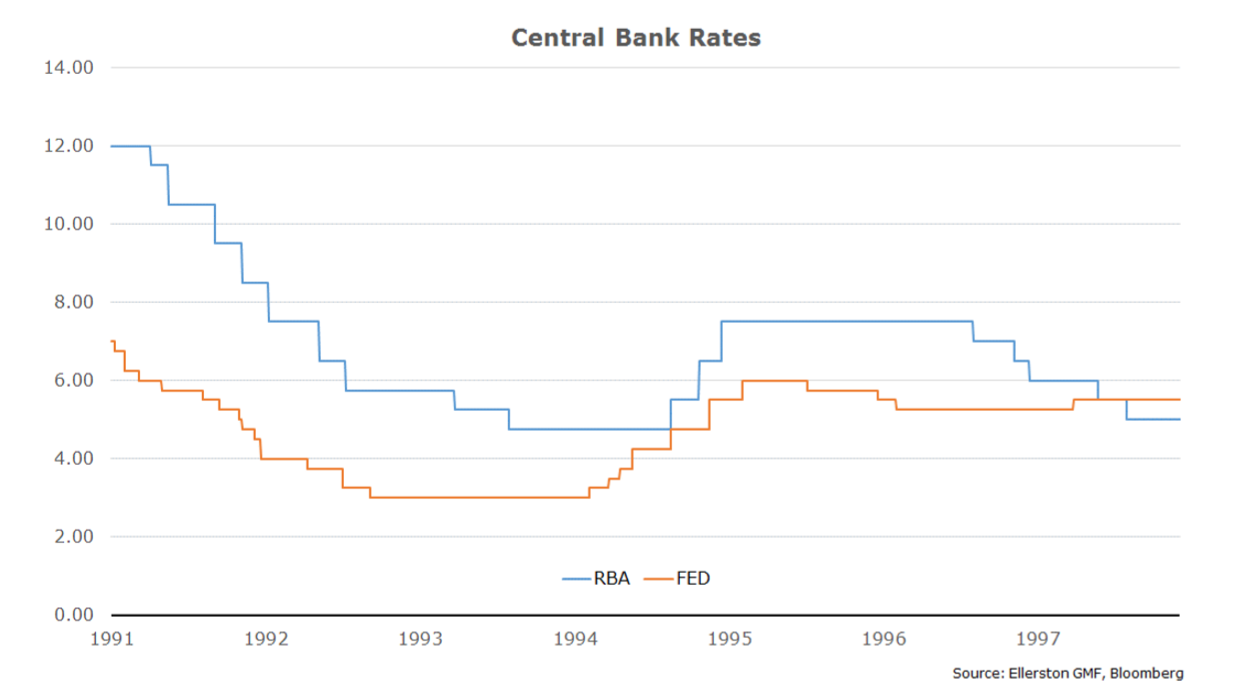

Why? At this stage in my career, my sources of alpha, the asset markets that I would take risk in, were much more limited. Indeed, 90% of my risk was either in Australian interest rates or US interest rates. And why not? In the first half of the 90’s they moved a lot. An awful lot, particularly in Australia.

And then in 1995 the RBA didn’t change rates at all. Not once. What’s more, at the start of 1996, I judged there was little prospect of them changing much either. At least compared to the US, who had made 3 adjustments during 1995. So I made a dramatic decision. For 1996, I would work nights and trade the US market. Yes arrive at work at midnight, just before the US open, and leave at 7:30am, just after the close. I figured why not? There would likely be more moves by the Fed than the RBA, and I could have some time at home with the new baby. Win, win!

Now I don’t know if I would go as far as to say lose, lose, but perhaps it was not the optimal decision for the year. As it turned out, the Fed only moved once, but the RBA moved 3 times. Indeed, it was the year that made Rory “rate cut” Robinson famous in Australia, for unilaterally calling the RBA rate cut in August 1996. Whilst I was twiddling my thumbs on the night shift…

And being home with the new baby? That proved a little more work than expected, not least because my wife was pregnant again 11 weeks after the first birth and in bed/hospital with morning sickness for 3 months. But cherished memories, of course…

And why is 1996 so interesting for you?

Well firstly, because I am now gunning for the Brett “rate cut” Gillespie mantle. (Jump to the end of this note for my take on Australia). And secondly, because Powell loves it as an analogue. In his August 2018 speech at Jackson Hole, he points to the “considerable fortitude” of Greenspan.

The second half of the 1990s confronted policymakers with a situation that was in some ways the flipside of that in the Great Inflation. In mid-1996, the unemployment rate was below the natural rate as perceived in real time, and many FOMC participants and others were forecasting growth above the economy's potential. Sentiment was building on the FOMC to raise the federal funds rate to head off the risk of rising inflation. But Chairman Greenspan had a hunch that the United States was experiencing the wonders of a "new economy" in which improved productivity growth would allow faster output growth and lower unemployment, without serious inflation risks. Greenspan argued that the FOMC should hold off on rate increases.

Over the next two years, thanks to his considerable fortitude, Greenspan prevailed, and the FOMC raised the federal funds rate only once from mid-1996 through late 1998. Starting in 1996, the economy boomed and the unemployment rate fell, but, contrary to conventional wisdom at the time, inflation fell.

I was on the receiving end of the “considerable fortitude”, spending endless nights positioning for rate hikes in 1996 as the unemployment rate moved below “the natural rate perceived at the time”.

It’s worth reading the whole speech, because this is when Powell first started to hint at his true colours. He dismisses the 1960’s analogue (where the Fed lost control of inflation) because inflation expectations weren’t well anchored, (despite two decades of 2% inflation!), and dismisses work from his own Fed that said if you don’t know what level of unemployment generates inflation, pay attention to the change in the unemployment rate as a guide of when to be concerned.

So we had a hint of the dovish Powell. But then in October he went all hawkish on us, declaring we were a long way from neutral interest rates. Ignore his August speech. He was of bona fide Fed DNA, ready to follow Fed orthodoxy and stand guard against excesses in the economy that might generate inflation (or bubbles). And then we saw the worst December for equity markets since 1931. Followed no less by the best January since 1987!

Fair to say a few heads are spinning. To understand the last two months, you need to understand just one thing. The Fed committed Seppuku.

Who at the Fed committed the “honourable death”? It was not an individual, but rather an orthodoxy – the Phillips curve.

Think of Powell as the dagger. And in true seppuku a samurai stands behind the practitioner and once the disembowelment is completed chops the head off. Perhaps Trump is the Samurai…?

I digress.

So let’s first “dissect” what Powell did, and then consider the implications. Last month I referred to the Powell capitulation on January 3rd, and the possibility we were about to repeat the 2016 analogue. On the 31st January the Fed met, and the ceremony was performed. Of course the Fed statement and following press interview by Powell didn’t explicitly acknowledge that the Phillips curve orthodoxy has been terminated. But the actions did. What were they?

- They removed the reference to more gradual hikes being required. ie the next move in rates could be up or down.

- They indicated they would adjust the wind down of the balance sheet if required.

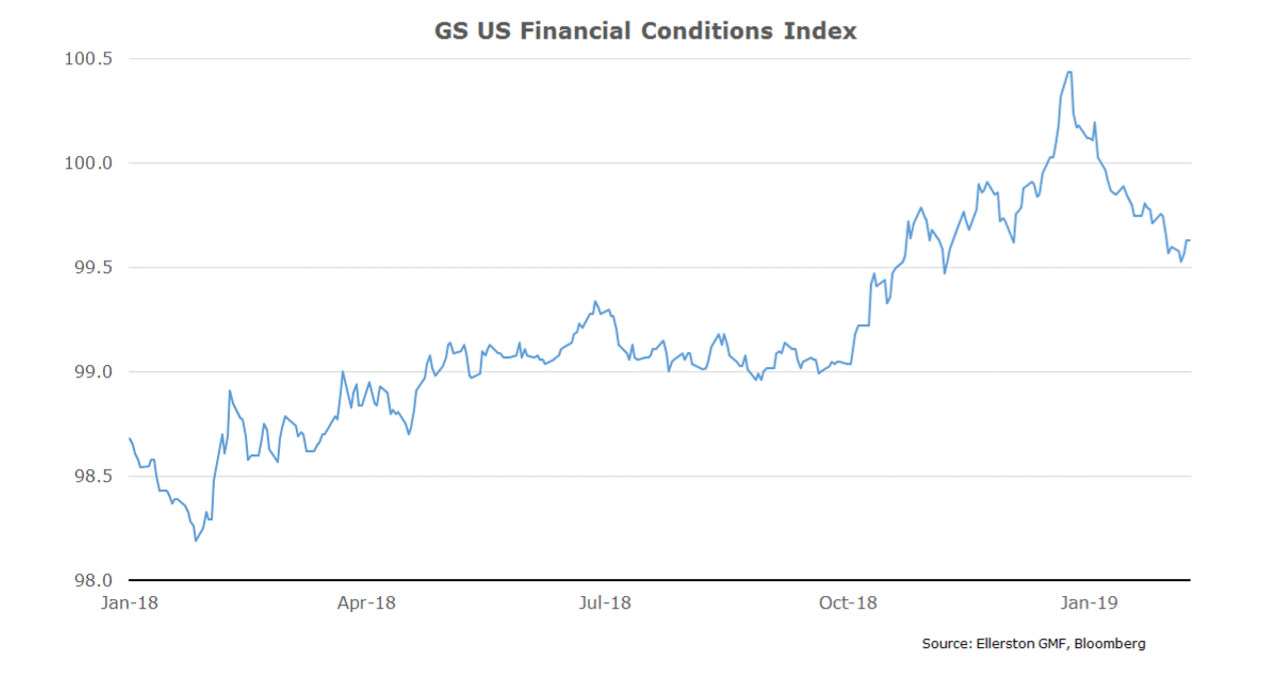

In the press interview Powell was questioned repeatedly about a “Powell put” in the equity market, and what had changed so much from the December meeting to this meeting? He was clearly uncomfortable explaining the about face. But he made two things clear. Firstly, it “was all about financial conditions”. And secondly, he will now wait to see inflation before increasing interest rates again.

Sounds reasonable no? Only to a layman. Monetary policy operates “with long and variable lags”. Around 18 months to 2 years. And inflation also operates with long lags. So the Fed has to anticipate inflation and adjust monetary policy well in advance if it is to control inflation. Hence the 40 year reliance on the Phillips curve – the relationship between the unemployment rate and inflation. Or the wages Phillips curve (unemployment v wages). A belief in this relationship has allowed the Fed to act in anticipation of inflation for the last 40 years. And it has worked so well, that we have never seen inflation. Which has led to the discussion of the so-called “flattening of the Phillips curve”. That for ever lower unemployment rates we are seeing less and less reaction in wages and inflation. Which in turn has led policy makers, including Powell, to question whether the Phillips curve is now a reliable tool. On January 31st, he came out of the closet. He no longer believes in the Phillips curve.

Wow, wow, wow. This is monumental. Make no mistake. And it is monumental whether he is right or wrong. Because first and foremost what it means is the Fed is going to let the economy run much hotter. No “taking away of the punch bowl”. No sirree! Let’s party!

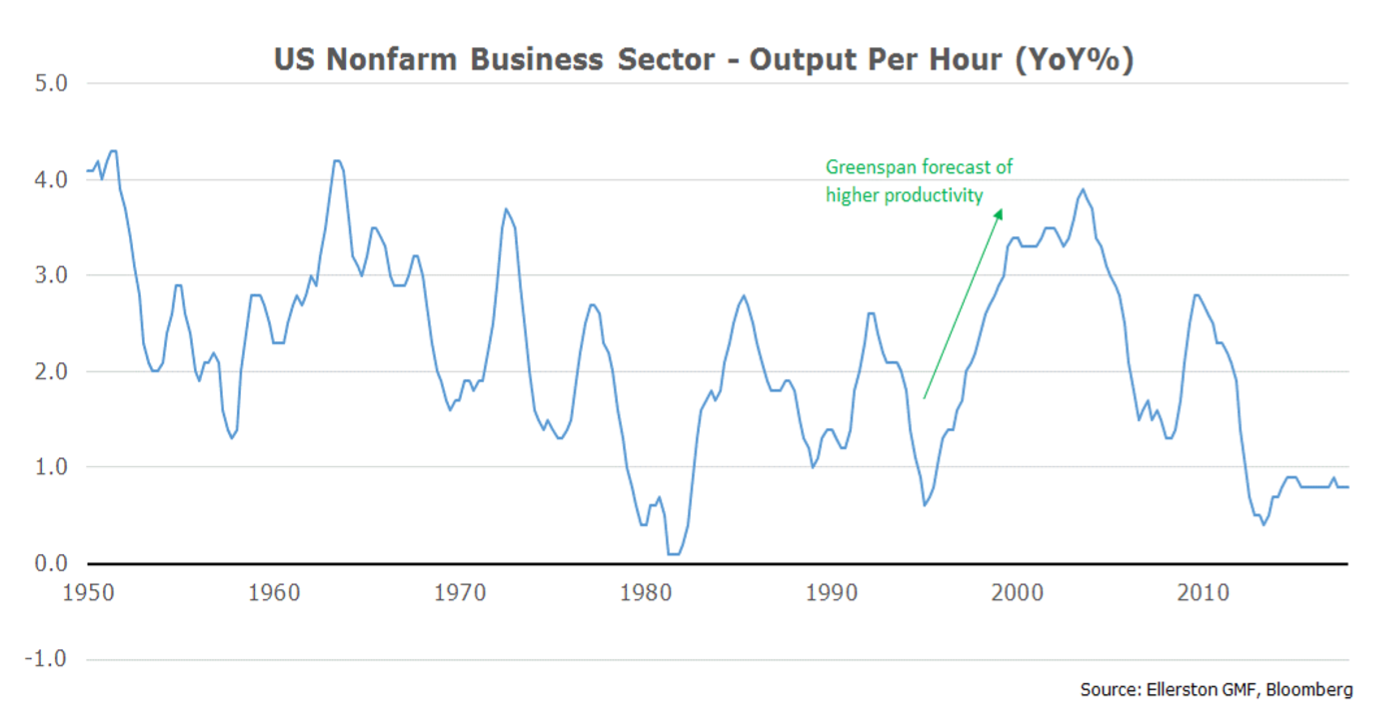

Will there be consequences? “No!” Powell says. It’s just like 1996, when Greenspan made a similar decision. Well, a similar decision to run the economy hot. But for a different reason. In 1996 Greenspan correctly identified an internet driven lift in productivity. And indeed productivity did lift to over 3% for 3 years, from an average 1.75%. And given potential growth (the rate of growth that doesn’t generate inflation) is the sum of productivity growth and population growth, the economy could indeed run over 1% hotter for a period.

But this time we have not had a lift in productivity – at all. Will it rise? Well as one of our very experienced consultants said in our last monthly meeting, “Productivity is the hardest variable to forecast. And to forecast a convenient rise in productivity just when you need it is rather wishful thinking”.

Indeed, Powell isn’t explicitly forecasting a lift in productivity. Though he has suggested it. He is explicitly questioning whether the Phillips curve works anymore. Has technology, global competition or some other force caused wages to no longer rise when workers are scarce? Apparently so.

Except we find no evidence of this – at all. But what we find doesn’t matter for markets – today. It will later this year…

So what happens now? Powell has declared he wants financial conditions to ease. Even more. By the Fed meeting last month, they had already reversed the tightening in financial conditions in November and December. He wants more.

This is exciting stuff for macro. Very exciting. Why? Firstly, because the outlook for the next 3-6 months suddenly became a lot clearer. And secondly, because in our opinion the Fed is setting up for a massive policy mistake.

That’s rather arrogant of me no? Unfortunately not. Mistakes by central banks are continually repeated throughout post WW2 history. Usually exactly the same way as Powell is about to – namely letting the economy run too hot, creating inflation and an asset bubble, and then causing a recession as they try and tame it. No one likes the punch bowl taken away…

So what is the scenario? Recall the three scenarios I have been writing about the last few months.

Scenario 1: Benign outlook

- Wages matched by productivity gains/Inflation contained.

- Fed moves to neutral/modestly restrictive, treasuries 2.8-3.4%.

- Business cycle extended, equities positively re-rate.

Scenario 2: Inflation rises

- Policy has not been this easy since the 60’s. Inflation accelerates.

- Fed cash rate and 10 year yields move to 4-5%.

- Recession risk surges, equities crash.

Scenario 3: unwind of credit yield chase

- Global credit markets crash/rerate.

- Tightening in financial conditions dramatically slows growth/cause recession.

- DM equities crash, Fed aborts, rates rally.

And last month wrote:

I still think the 3 scenarios are the right framework. And in 2019, markets could embrace all 3 at various times. But labour markets are too tight and credit exposures/debt levels too high. Eventually all roads lead to 3. Moving between scenarios will continue to create large market moves which we believe will provide both large opportunities and large risks for investors. We continue to focus on keeping risk limited and risk/reward high, and are very excited about the opportunities we see/expect in 2019.

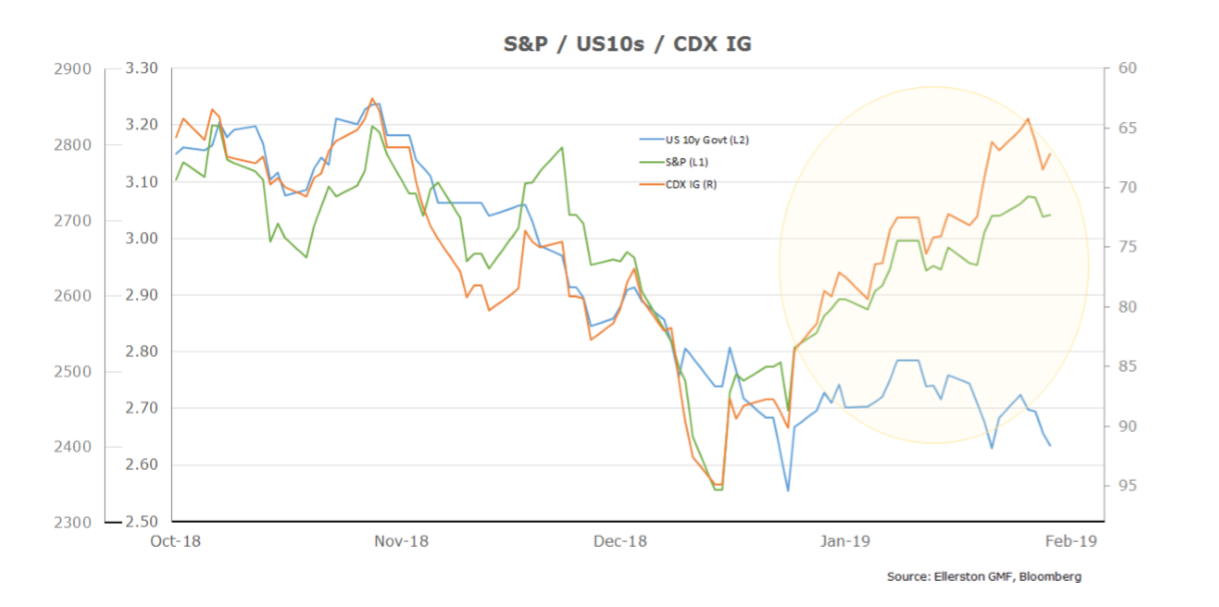

The month before, the end of November, we were biased to scenario 3, and positioned “short” credit in November, December and the beginning of January. One of the instruments we were “shorting” was CDX IG, which is a derivative that represents the cost of insuring investment grade corporate bonds against default (in the US). We had bought the CDX around 70, and bought options for the CDX to go to 120 by March. It was looking good, very good, until Powell’s seppuku.

As I said last month, eventually all roads lead to scenario 3, where we see this chart explode higher from corporates defaulting in a recession/credit bubble bursting sparked by Fed tightening. But not yet. Powell has firmly laid down the gauntlet. There will be no pricing of recession risk under his charge (at least if he can help it).

And so now the market knows one thing. Growth is going to be stronger in 2019 than they thought. The Fed WILL ease financial conditions. Whether it causes an inflation problem is up for debate. And that is the point. The market can’t be sure about inflation. The Fed tells them not to worry. But they can be sure about growth. And the Fed having a high hurdle to hike. So the market has to embrace scenario 1. And worry about scenario 2 if/when it emerges. Given that will take 6 months, possibly a little longer to be resolved, the market has no choice but to embrace scenario 1. For now.

Since Powell’s interjection, bonds have tracked sideways and equities and credit have rallied.

It is a time to be long equities, at least for the next 6 months. With one caveat. Well several really. There is still a lot of event risk to get through in the next month; US/China tariff negotiation, Brexit, even another US government shutdown. If/when these are cleared, expect 3-6 months of a grinding equity rally. We started February long equities but have already trimmed as tariff tensions flair and will look to engage if resolved.

Nothing much will happen in rates for now. So we don’t have a lot of risk there (modest positions for a Q3 hike from the Fed). We need to wait for scenario 2 to be triggered. We will build risk for that scenario as time passes and financial conditions ease further (from equities and credit rallying).

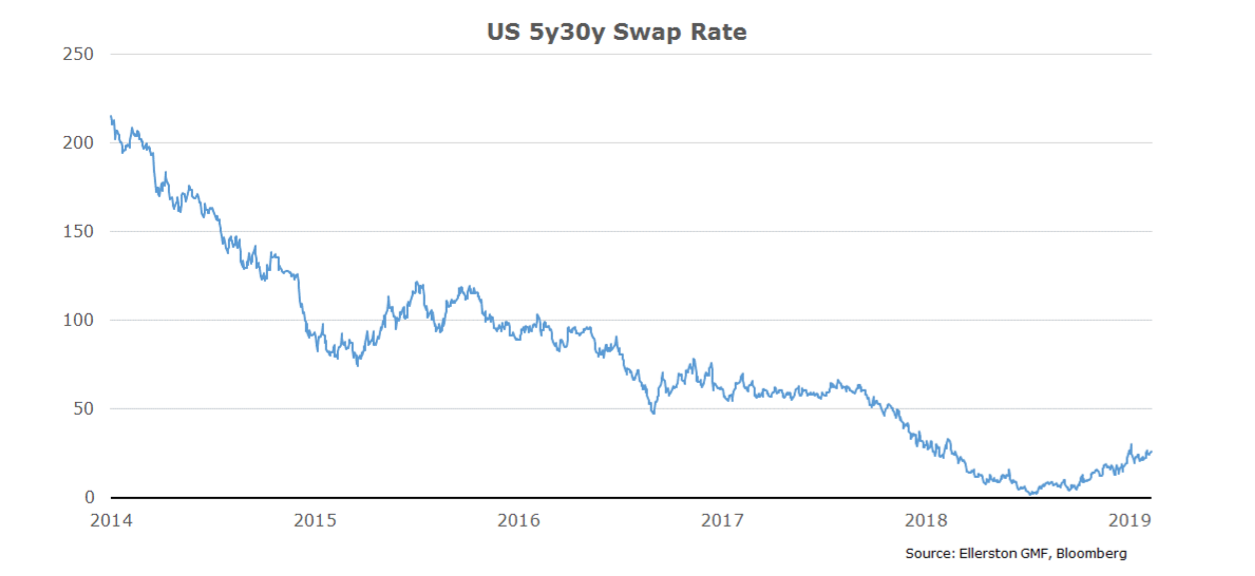

Will that take long? Sort of. Because the Fed’s reaction function has changed. They are no longer going to hike just because growth is strong and unemployment is falling to 50 year lows. That means the US curve will likely steepen. Bear steepen as the 5 year rate is anchored. The long end (30 year) moves higher as the market builds some inflation premium, higher real rates due to stronger growth, and continues to unwind the suppressing effects of quantitative easing.

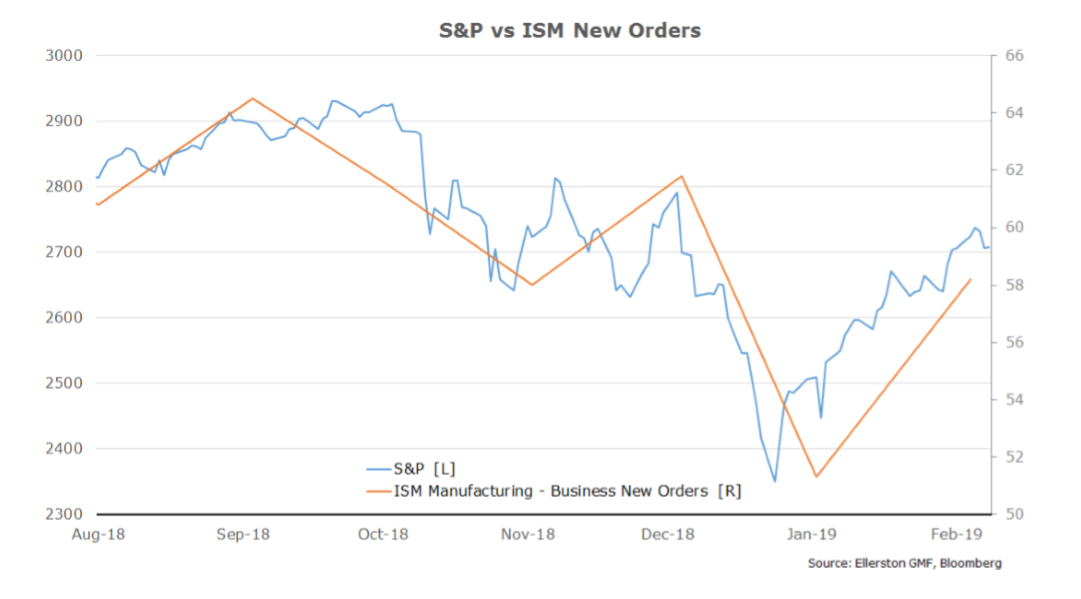

Activity data is likely to be stronger than expected in coming months. Yes stronger. Remember the US economy had a lot of momentum into the end of 2018. It was only going to be weak in 2019 because of the sharp tightening of financial conditions driven by the fall in the equity market and the higher corporate bond spreads. But they are now reversing. Quick smart. And the only “weak” data we have seen so far was survey and confidence measures falling. Not real activity. So the survey of manufactures plummeted in January. Because everyone expects a recession when the equity market falls 8% in one month. But it will also improve with the bounce back in equities in January. Indeed, look at the snapback in “new orders” on Feb 1 in the ISM manufacturing survey. Who’s watching equities?

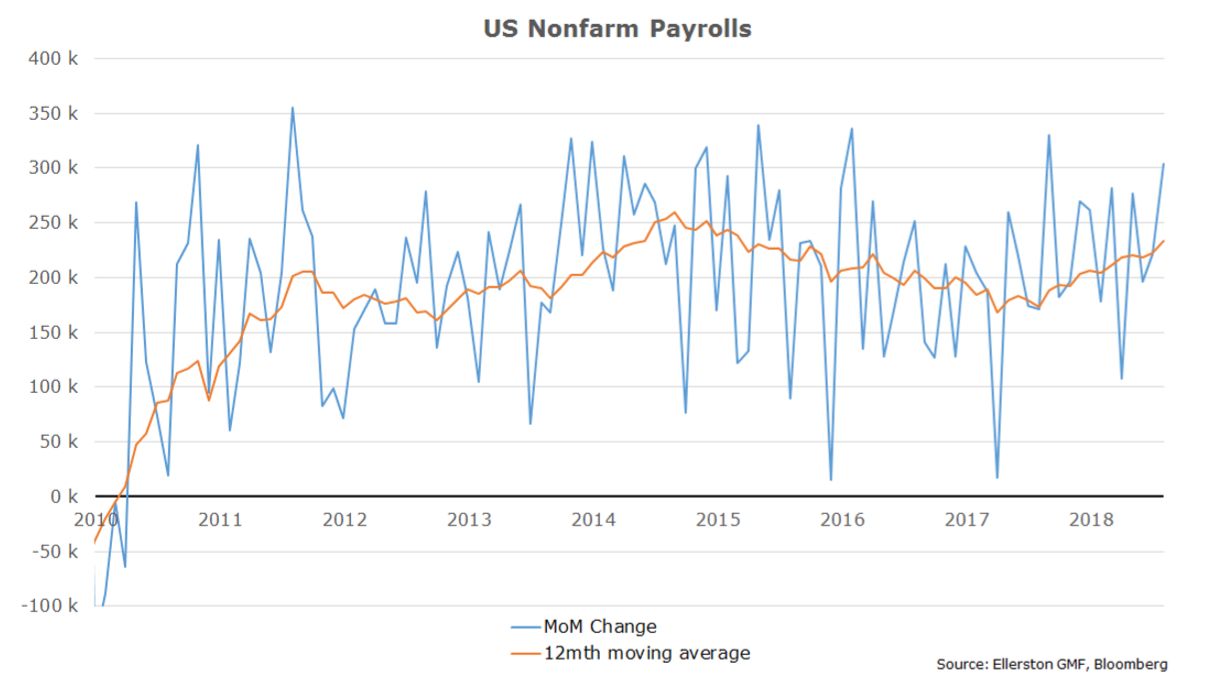

And if confidence returns, well the real economy hasn’t missed a beat. Indeed, look at the steady improvement in the 12 month average employment gain. Again, as of Feb 1, 234k per month. It doesn’t get much better than this.

So we are excited. We have, for the last few months, been working with 3 scenarios, and reluctant to engage a lot of risk until the scenario was clearer. We thought the market and the data would dictate the scenario. But Powell has decided too. That caught us a little by surprise, but hey, now it is game on. Play scenario 1 for 3-9 months, and be ready for scenario 2 – the Fed loses control. There will be good opportunities in scenario 1. We just have to get the tariff brinkmanship and Brexit decision out of the way…

But there will be tremendous opportunity in scenario 2 – both the Fed trying to tame inflation, and the inevitable recession. Fun, fun, fun – at least for macro…

The trades? Equities rally grind a low volatility “climb the wall of worry” rally for 3-9 months. And credit spreads narrow. Bond yields consolidate, then drift higher. In that window, as mentioned, we like long equities and 5-30 year steepeners. Then sometime in 3-9 months all hell breaks loose. The Fed has to hike, but is late. So they have to hike more. Equities (and credit) smell a recession. And so crash. All the more so in the case of credit, given 10 years of inflows under QE. And the Fed delivers a recession as they fight to tame inflation. All rather ugly. Unless you can play the game. Like macro can.

We also still have our positive Brexit trades on in EURGBP. If over coming months we see either May’s plan pass, a customs union plan pass, or a referendum is called, we expect to make about an 8:1 return. We are currently risking about 0.4% of capital to make 3.2%. And feeling more confident of a positive outcome this month than last month, despite the delays.

And finally AUSTRALIA gets interesting.

I think there is a 60% chance they cut rates this year. And if they cut, they will cut twice.

This is a big change for us. Towards the end of last year we still thought the RBA would be on hold, with a move up sometime in 2020. So what has changed? The data, and now the RBA’s tone. And it was two indicators in particular.

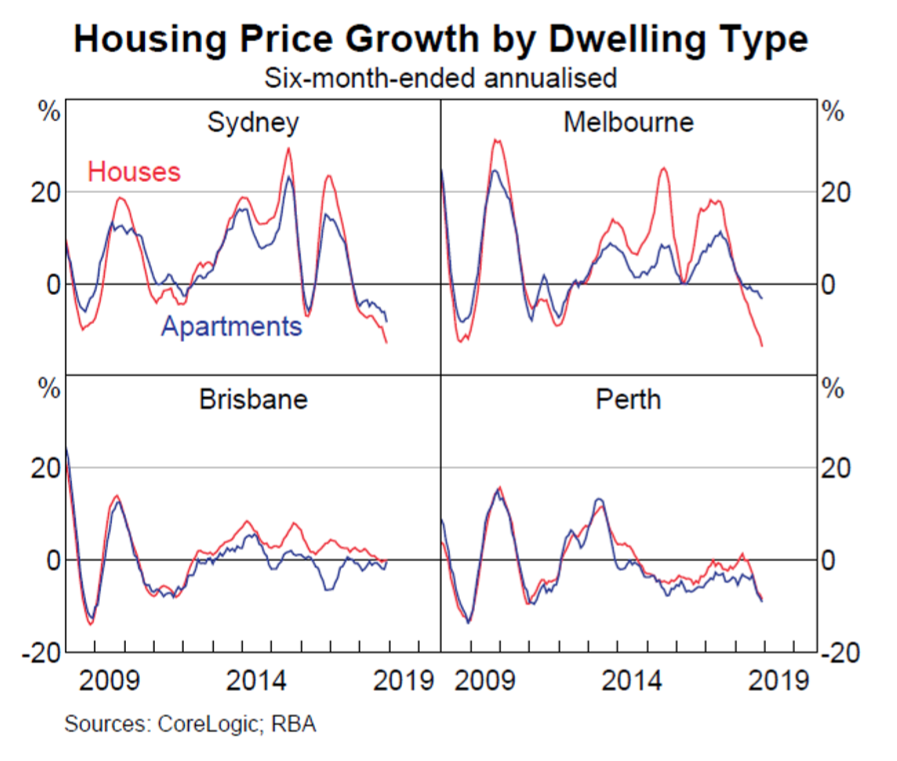

1. The housing market decline accelerated.

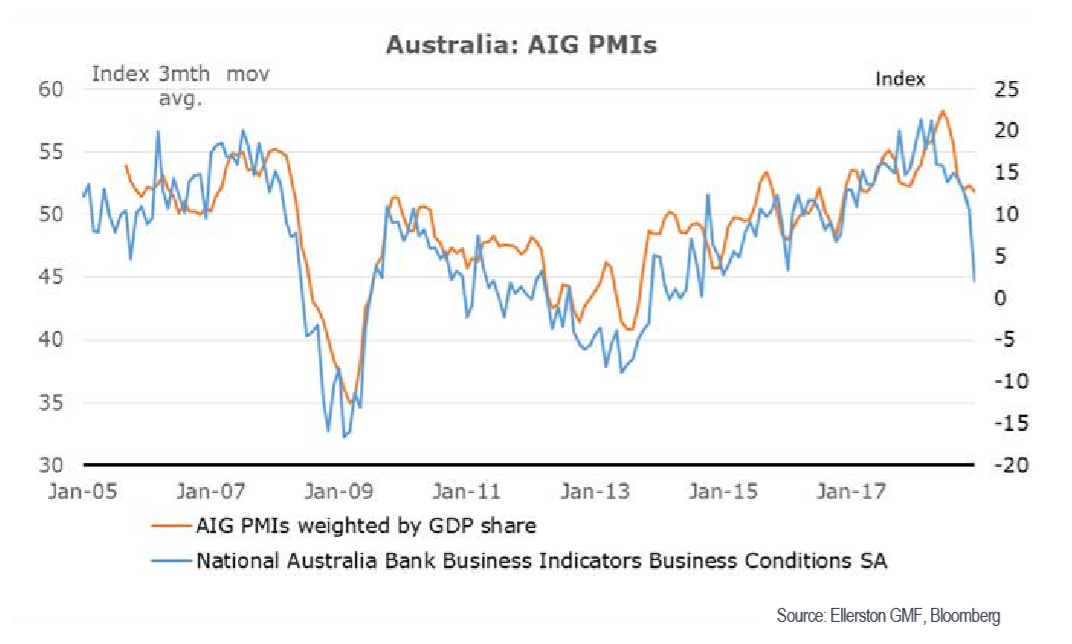

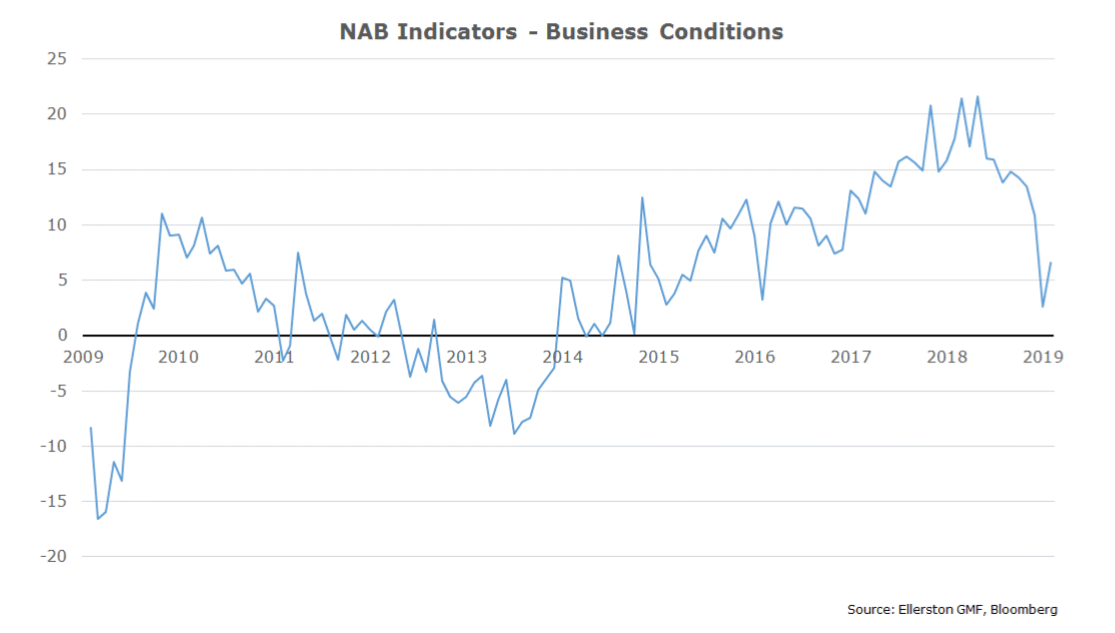

2. The business survey’s collapsed.

Source: Ellerston GMF, Bloomberg

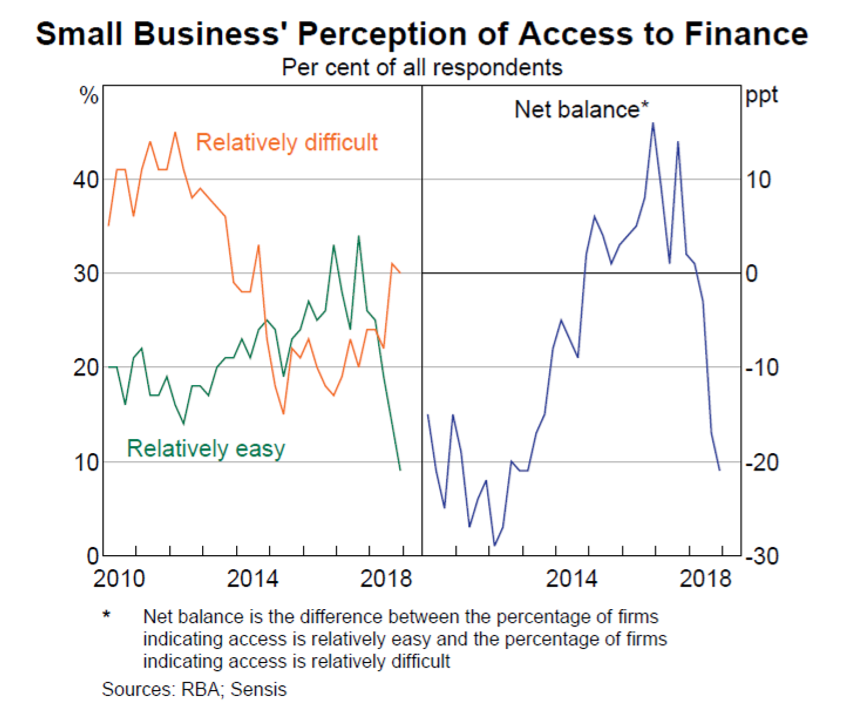

In addition, I have been hearing anecdotes that small business lending (loans under $500,000) have essentially stopped as a consequence of the Royal Commission. So I found this chart particularly interesting from the RBA’s Statement on Monetary Policy in Feb.

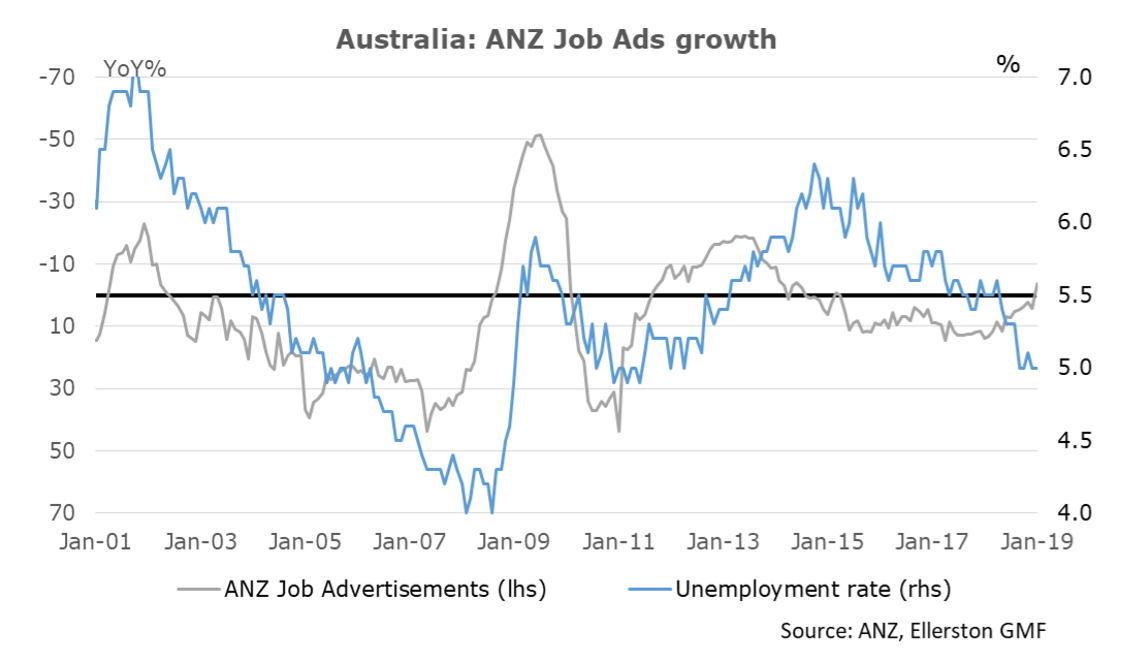

Some think the RBA won’t cut unless unemployment rises, particularly because it is at 6 year lows. Certainly Lowe has suggested that. But historically the RBA looks at where unemployment is going, not where it is. And the lead indicators suggest the unemployment rate is about to move higher.

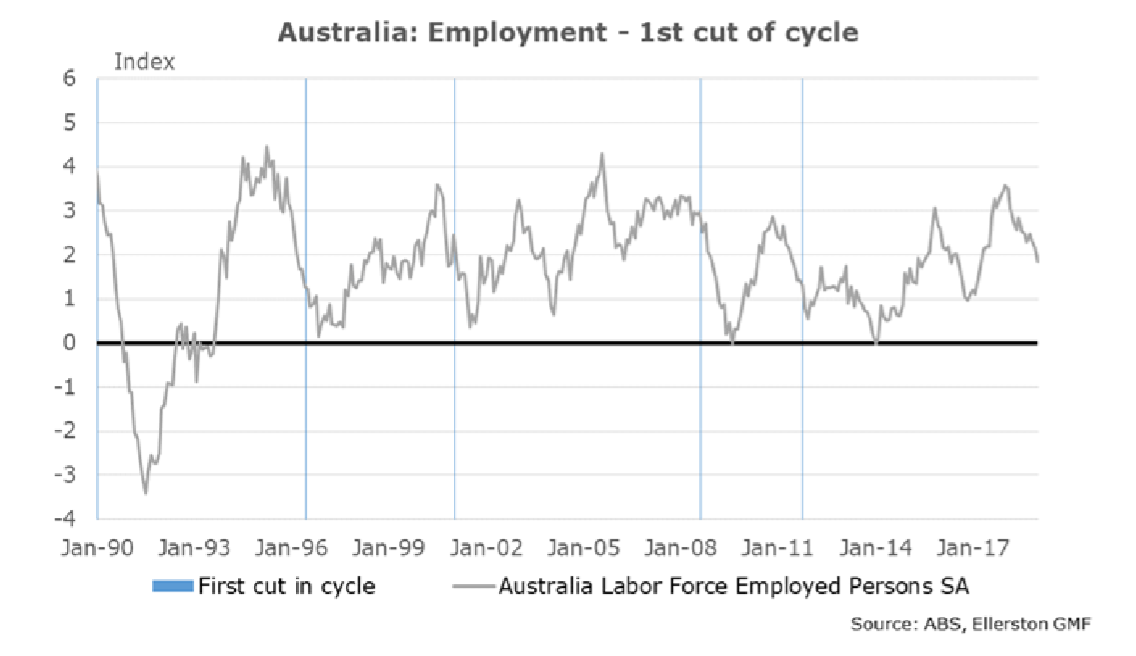

Indeed, the first rate cut of a cycle has often occurred in the past well before employment drops.

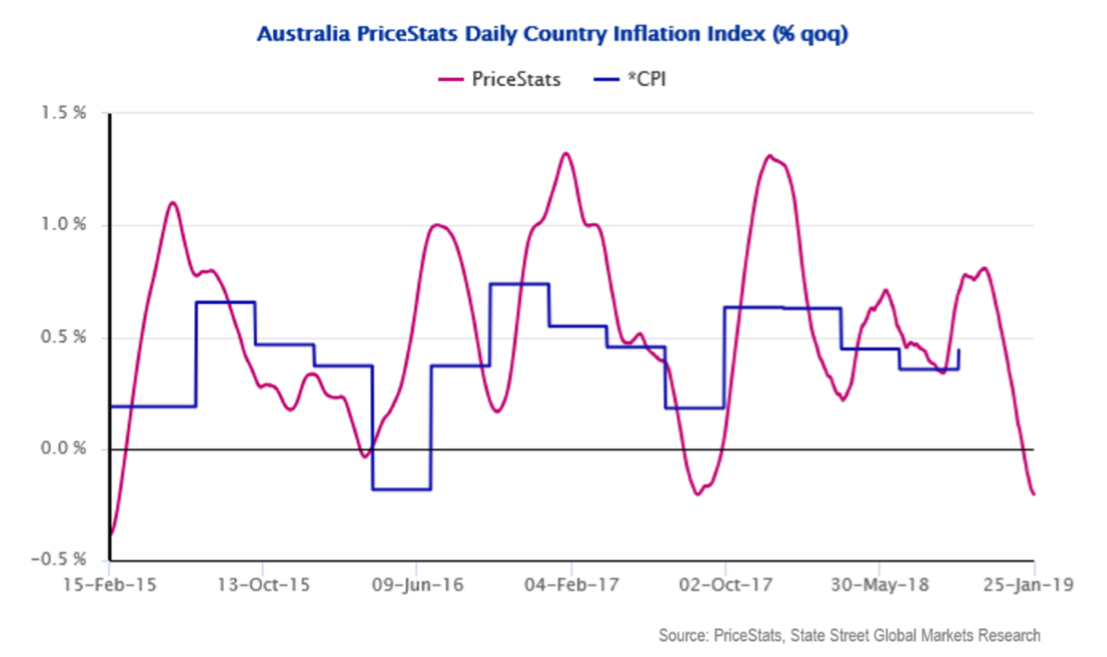

Meanwhile, trimmed inflation has been below the RBA’s target of 2-3% for 3 years. And price stats suggest it is going to weaken further.

And then there is the election in May. Suffice to say it is going to make the bid in housing “soft”. Glenn Stevens, as Governor, was fond of an expression – “the policy of least regret”. Now I don’t know if Philip Lowe is fond of the same expression. But hopefully he is thinking in those terms.

And he should be thinking like this; if I do nothing with interest rates in coming months, the fall in house prices might continue to accelerate, particularly with an election looming. This would hit consumption hard, which we saw early signs of in Q4, and meanwhile the business confidence fall would be re-enforced, meaning businesses would cut back on investment and hiring and the recession would become self-fulfilling.

Alternatively, if I cut interest rates, I would stand a reasonable chance of not allowing that cycle to develop. I would certainly not expect it to lift house prices – one cut would not be enough to do that, but I rest easier on the tail risk. And inflation? There is neither any wage inflation nor inflation at present, and on their own forecasts they are struggling to get to target over the next 2 years. That’s not a risk.

On a policy of least regret framework, it seems very straightforward then doesn’t it? So what has Lowe done? On Feb 6th 7 he has given himself optionality (my underlining).

Given the uncertainties, we are paying very close attention to how things evolve.

And

…it is possible that the economy is softer than we expect, and that income and consumption growth disappoint. In the event of a sustained increased in the unemployment rate and a lack of further progress towards the inflation objective, lower interest rates might be appropriate at some point. We have the flexibility to do this if needed.

The question one has to ask is “Why wait?” “Sustained” would suggest he would like to see several months of data. And that is what the market has concluded. Now he may wait. I don’t know. We don’t have a track record with Phil Lowe. He seems to be heavily influenced by his models, and seems to prefer to move very incrementally. Or will he retain some of the instinct of his former bosses, and move decisively and early when the need arises?

But I will say this. The hurdle for a rate cut from the RBA is low. They never respond to one month of data. And so their assumption is that the very weak data at the end of last year will bounce back (somewhat). If it doesn’t, a rate cut could come very soon. As I write we have had the NAB business survey. It was not much of a bounce back…

And there is also that little problem of the election. With growth already shaky, do you want to take a risk that it steps lower as election uncertainty bites? Do you want to move rates during the election, or even the month before? Not really. And so do you want to cross your fingers and wait till June? That’s the policy of least regret?

To me, the policy of least regret is fast becoming an insurance rate cut in the next month or two. And at 10:1, we are risking some capital on that. But our higher confidence is there will be a rate cut in the 3 months after the election (whether it is the first or the second!) And so we are risking even more capital on that (currently about 0.5% to make 1.5 %).

In summary, we are positioned for:

- Rate cuts in Australia.

- A positive Brexit outcome in the next two to three months.

- An on-hold Fed driving a benign market conditions in the US for the next 6 months or so, before the Fed hikes again in Q3.

The die is cast…

Never miss an update

Stay up to date with the latest macro news from Ellerston Capital by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

Want to learn more about big picture investing? Hit the 'contact' button to get in touch with us or visit our website for further infomation.

2 topics

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.