Housing bears becoming bullish

In the AFR I write that as it becomes increasingly clear that the numerous deeply pessimistic predictions for the Aussie housing market will not be realised as home values stabilise six months after the original March COVID-19 shock, some bears are dropping their dour outlooks and becoming much more bullish. Excerpt enclosed:

One of the first of these transformations has occurred at CBA, which in April forecast that house prices would fall by 10 per cent nationally. CBA’s projections were actually quite optimistic compared to the consensus, which was divining cataclysmic price declines of between 10 per cent and 30 per cent.

Our more modest position expressed in March 2020 was that national dwelling values would only decline by zero to negative 5 per cent over a six month period following which the market would rebound robustly with capital gains of 10 per cent to 20 per cent over the next 1 to 3 years.

In the dark days of the COVID-19 crisis this view attracted visceral criticism. It had nothing to do with the suggestion that we are preternatural housing bulls: when prices were still rising in early 2017 we were the first mainstream analysts to predict the subsequent 10 per cent correction between late 2017 and early 2019. Along similar lines, this column was the first to call for the end of that bust and a 10 per cent increase in house prices in April 2019 on the back of an expectation the RBA would slash rates, which is what came to pass between June 2019 and April 2020.

These forecasts can therefore be positive or negative depending on what analysis of the data tells us.

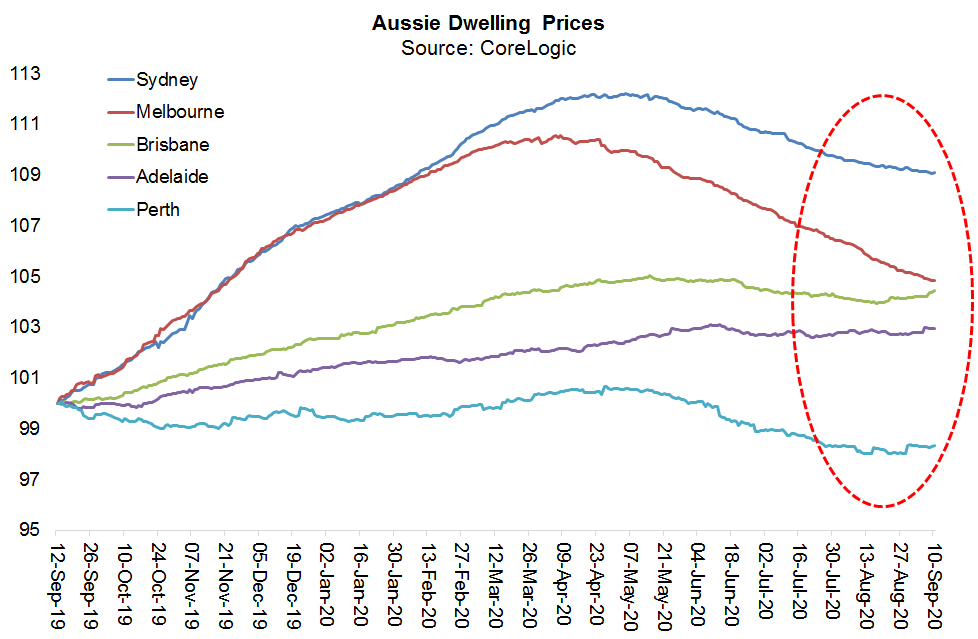

At present the CoreLogic indices clearly show that six months after the March shock house prices are gradually stabilising or starting to slowly climb again in Sydney, Canberra, Adelaide, Brisbane and Perth. Melbourne is the one big exception. If it were not for Melbourne’s surprising second wave and savage ensuing lockdown, the current Aussie housing turnaround would be sharper.

In a research report published this week, CBA’s economics team noted that in April 2020 their “central scenario was that dwelling prices nationally would fall by around 10 per cent from their April peak”. With the benefit of the information that has emerged since, CBA concedes that “the fall in dwelling prices to date has been a lot smaller than we anticipated”.

CBA had expected prices to fall by 10 per cent in just six months. In practice, national home values have slid by around 2.5 per cent, which is coincidentally at the mid-point of our proposed zero per cent to negative 5 per cent forecast range.

“Parking the Melbourne issues to one side, what has genuinely surprised us is the resilience of house prices in some of the other capital cities considering the negative shock to labour markets around the country,” CBA’s economists reveal.

While CBA still believe national prices will continue to ease, they’ve substantially revised their outlook: “we are now looking for a national peak-to-trough fall of 6 per cent versus our previous call of 10 per cent”. And they are forecasting “solid price growth in the second-half of 2021 as the economic recovery gains traction and incredibly low interest rates once again become the dominant influence on dwelling prices”.

More specifically, CBA think that house prices will rise at a 6 per cent annualised pace over the second half of 2021. Here they share our view that the radical improvement in purchasing power as a result of the huge reduction in mortgage rates “will once again become the dominant driver of dwelling prices”.

“The RBA has tended to play down the influence of monetary policy decisions on dwelling prices,” CBA says. “But we believe that changes in interest rates are the single most important driver of real property prices over the longer run.”

We’ve previously highlighted the RBA’s internal research which finds that a permanent one percentage point decline in mortgage rates from early 2019 levels could propagate a 28 per cent increase in home values. Aussie households captured the first 10 percentage points of that rise between June 2019 and April 2020.

Accounting for the tiny circa 2.5 per cent drop in national home values since April 2020, we are still theoretically owed house price appreciation of another 10 per cent to 20 per cent. (One could argue for potentially larger gains since many home loan rates have declined by more than 100 basis points since early 2019.)

The most accurate bank to date has been Goldman Sachs’s economics team, which in April projected only a 5 per cent decline in national prices, which they argued would then be superseded by strong capital gains of between 10 per cent and 15 per cent over the next 2 to 3 years. While Goldman Sachs is retaining its core call for a 5 per cent national draw-down, it has become more bullish: “we now expect to see a more front-loaded rebound of 10 per cent over the next twelve months”, which will be supported by the resumption of solid net overseas migration.

The latter is a feature of our outlook, which has encouraged the government to aggressively ramp-up its efforts to attract top talent and capital fleeing COVID-19 ravaged areas and the extreme political instability in Hong Kong. The Prime Minister Scott Morrison and Treasurer Josh Frydenberg have of late talked-up the prospect of a global war for talent and the much-needed return of foreign students to Australia’s ailing education sector. On the ground, leading real estate agents also report a surge in interest from both expatriates and Asian investors seeking a relative safe harbour in the form of Aussie housing.

Beyond the dramatic recent increase in purchasing power, term deposit rates dropping well below 1 per cent are also fuelling a search for superior returns. And we expect the investment narrative to increasingly concentrate on the advent of “positive gearing”.

According to CoreLogic, gross rental yields on apartments in Canberra (5.7 per cent), Adelaide (5.4 per cent), Perth (5.3 per cent), Brisbane (5.2 per cent), Hobart (4.8 per cent), Melbourne (3.9 per cent), and Sydney (3.4 per cent) are all significantly higher than the interest repayments on home loans. Property investors used to claim tax deductions from "negative gearing"—in most Australian cities today they can actually make money from rents net of their transaction costs.

The recovery in housing will be enormously helpful for consumer confidence and provide a positive feedback loop for household spending via the wealth effect as asset prices climb. This is, to be clear, precisely what the RBA is hoping to engineer.

A healthy increase in house prices next year will also be a fillip for the stamp duty revenues collected by state governments, which will in turn help them fund investments in productivity enhancing infrastructure.

Not already a Livewire member?

1 topic