How this cycle will (may) end

Quick Brown Fox

Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio recently gave an interview where he said he believes that we are in around the 7th inning of the current economic cycle. To spell it out, baseball games have 9 innings and so this suggests he believes that we are closer to the end of the cycle than the beginning. We would agree with this assessment and whilst we acknowledge that we don’t have a crystal ball (and this article does include plenty of speculation), there are some signs we are watching that look like late cycle indicators. In examining current economic conditions we have discovered that we are considerably more concerned with risks and vulnerabilities in the Australian economy at present than the US economy.

To understand the global economy, it’s important to look back to history. The story of the last 30 odd years is one of a credit super cycle in the developed world. This started back in the 1980s when interest rates started to come down from record high levels in the high teens. Globally, interest rates since that time have trended down towards zero as can be seen with the most important interest rate in the world, the Federal Funds Rate.

Declining interest rates combined with deregulation in the banking sector led to a huge boom in household credit. The banking sector globally took on more leverage. Prior to 1980, the global standard for banks was a leverage ratio of 7x, this has changed dramatically since. Just prior to the Global Financial Crisis, leverage in the European Banking system stood at 40x, in the US it stood around 30x and in Australia it stood at over 20x.

This increased leverage enabled more lending and lower interest rates meant households could service more debt. Household consumption over the period was a key driver of growth in the developed world whilst a large portion of the manufacturing base slipped off to China.

With increasing debt levels, households become more vulnerable to small changes in interest rates. From the chart above we can see that since the Mid 1990s each US recession has been preceded by a tightening cycle from the Federal Reserve. We can also see that every time the Federal Reserve has concluded a tightening cycle, the peak in interest rates has been lower the previous time. In 1989, the effective rate peaked at 9.85%, in 2000 it peaked at 6.54%, and in 2007/08 it peaked at 5.25%. This shows to us that whilst we love to talk (or complain) about politics, the key variable in economic cycles is interest rates and those setting them.

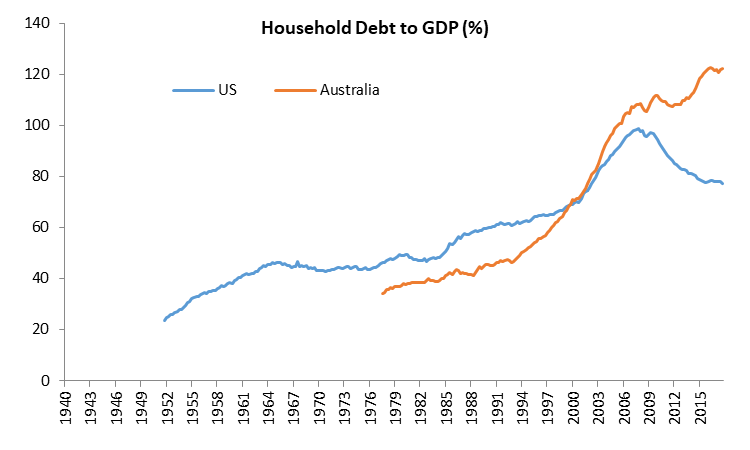

The question then becomes when will the Federal Reserve raise rates too far and what will the impact be? One of the key variables in this equation is household debt and one of the key differences in the US now as opposed to 2007 is that households have deleveraged.

Source: Bank of International Settlements

This deleveraging cycle has been a key reason why the economic recovery in the US since 2008 has been anaemic. However, the effect that deleveraging has is that it makes households less vulnerable. In addition the banking sector has deleveraged over this period with the help of bailouts and Quantitative Easing. As a result, a repeat of 2007/08 in the US, is unlikely in our view. Note that Australia’s household debt has continued to rise, more on this later.

The greater risk we see as interest rates rise is an increase in risk pricing. One of the side effects of low interest rates is speculation and malinvestment as investors are pushed into riskier assets to find returns. Currently the price of risk is low and we see that through credit markets where the high yield spread is currently at its lowest level since July 2007 (note it hit an all-time low earlier in 2007 at 241bp). Investors have driven spreads down as they currently see little risk; previous spikes in the chart below coincide with the GFC, the European crisis and the fall in the oil price.

Source: Pension Partners

As interest rates have come down over the last thirty odd years we have seen capital flow into the Tech sector back in the 1990s and in the early 2000s it flowed into real estate.

This time around a record amount of capital has flowed into private capital markets. This has increased competition in the space and pushed up multiples that private equity firms have to pay to buy companies. Risk is increasing in the space and we have seen our first major blow-up in Theranos. The story of which is covered superbly by John Carreyrou in his book “Bad Blood”.

There have also been other areas of speculation. Last year we saw speculation in Cryptocurrencies. In the listed space, we have record divergence between growth and value. We have also seen wild moves in speculative sectors such as Cannabis, most recently in Canadian company Tilroy. Last week saw its market capitalisation exceed $28 billion despite its revenue last half only being $20m.

Although they make for interesting stories, the fallout impact from Blockchain and Cannabis is likely to be small. What could have a bigger impact is the Information Technology sector which has been the key driver of sharemarket returns in recent times. We could get into a debate around the valuations of companies such as Amazon and Facebook (as well as potential regulatory risks) but we think the greater risk lies in a number of companies which are reliant on capital markets. The most notable and debated of these is Tesla.

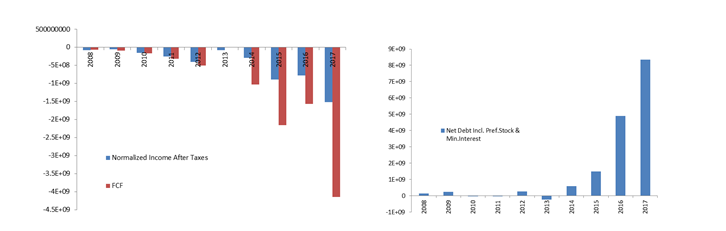

Proponents of the company claim that the company is revolutionising the car industry whilst critics point towards financial statements that are troubling. In fact, last year the company had negative free cash flow of over $4bn (followed by almost $2bn in the first six months of this year) and has accumulated a net debt position of over $10bn now. In fact the company has never made a single cent of free cash flow (as can be seen in the chart below) and is completely reliant on capital markets to fund their operations.

Source: Thomson Reuters, Company filings

The company reports next month and it is a crucial period as the company has $900m worth of convertible notes due in February next year. In order for conversion to be worthwhile, the company needs the share price up above $359 (currently $299). A major bankruptcy for a darling company such as Tesla could have a similar impact as the fall in Enron back in 2000.

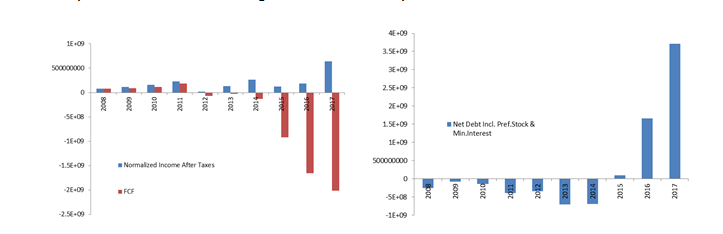

Tesla isn’t alone in this regard. Netflix, another market darling, is spending significant amounts of capital to create its own programs in response to a coming competitive threat from the likes of Disney. The result is an increasing cash burn funded by the debt market.

Source: Thomson Reuters, Company filings

Overall, the risks to the US are similar to the early 2000s. Back then an equity market fall led to a very mild economic recession. The fallout came from primarily from one sector and had a greater impact on asset markets than it did on the overall economy.

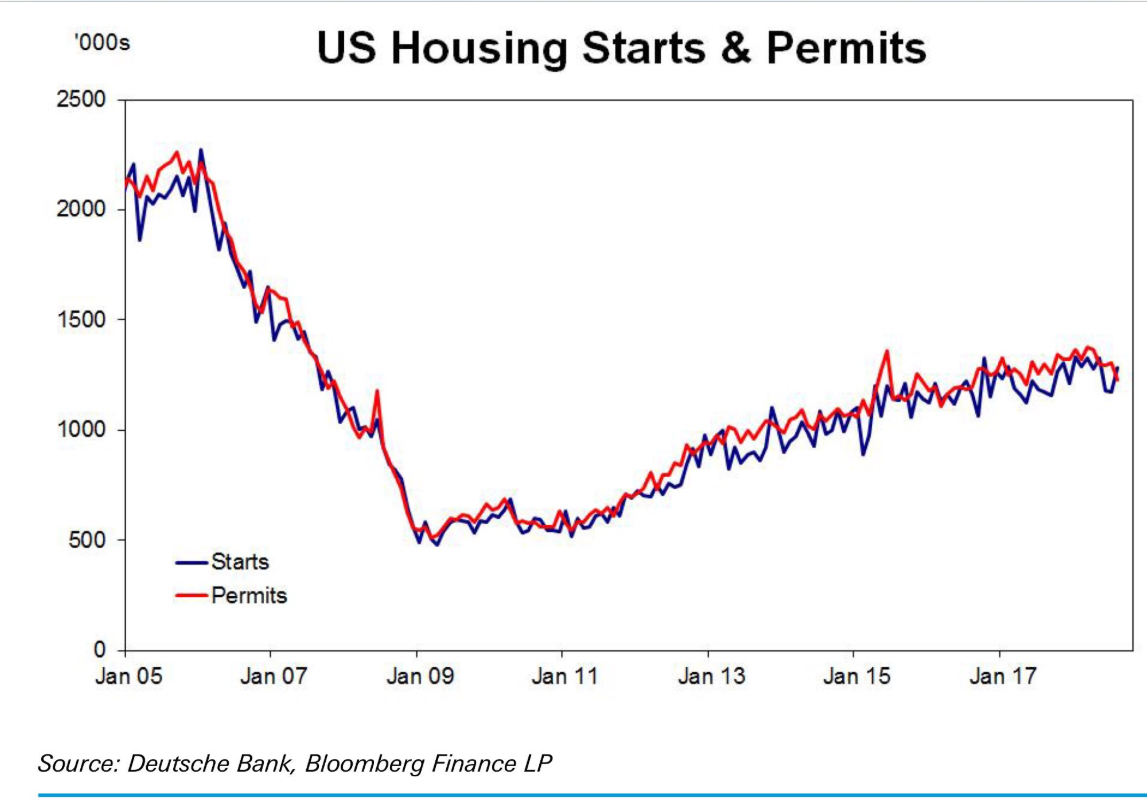

The other reason we don’t fear a major recession or crisis in the US is the housing market. Regular readers of ours will be familiar with Edward E. Leemer’s 2007 economic paper, “Housing is the business cycle”. In this paper, Leemer looks at all the recessions in the United States since World War 2 and finds that 8 out of the 10 were “preceded by substantial problems in housing and consumer durables.” This leads him to conclude that “Housing is the most important sector in our economic recessions, and any attempt to control the business cycle needs to focus especially on residential investment.”

The only two US recessions that are exceptions to the above were the end of the Korean War in 1953, caused by a decline in defence spending, and the 2001 “Tech Wreck”. As the paper was written in 2007, we can now improve the success ratio to 9 out of the last 11 recessions following the 2008 recession, something that Leemer warned about.

The key reason Leemer gives for housing being so important to the economy is that “house prices are very inflexible downward, and when demand softens as it has in 2005 and 2006, we get very little price adjustment but a huge volume drop. For GDP and for employment, it’s the volume that matters."

In other words, a housing cycle will typically see a drop in transaction volumes and building activity that will lead to job losses and ultimately a downturn in the economy. So it’s important to note that whilst housing activity has increased since the 2009 lows, it remains well below the 2005-2007 levels. Whilst a slowdown may occur, the overall economic fallout will be less.

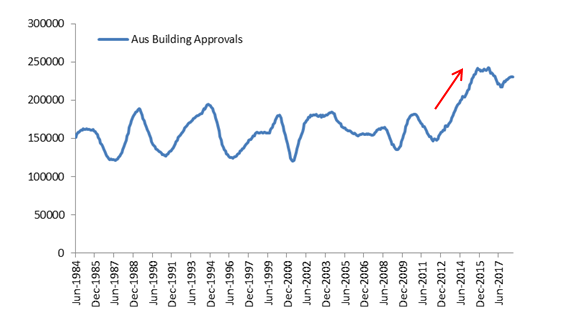

This of course brings us to Australia. Since they saw the end of the mining construction boom coming, the RBA have cut interest rates from 4.75% to 1.50%. The result has been that they have effectively replaced a commodities boom with a residential boom. Households have taken on more debt (as seen above). House prices have risen and construction has followed suit.

Source: ABS

After the experiences of countries like the US, Ireland and Spain in the early 2000s, organisations such as the Bank of International Settlements have warned that one of the worst things you can do to your economy is fuel a speculative real estate boom with cheap credit. Unfortunately the RBA and APRA weren’t listening.

Now that the residential boom is ending, we believe the fallout is likely to be bigger than any previous cycle. The reason we believe this is twofold.

Firstly, this boom since 2012 has been coupled with a record boom in residential construction. With demand starting to fall, supply (construction) is likely to fall and lead to a rise in unemployment. The multiplier effect from construction activity is large with all ranges of employment from developers, constructors, trades, property agents and financiers impacted. As we said above, we can see the impact of a fall in construction via the United States where 9 out of the 11 recessions they have had since World War II have been preceded by a fall in residential investment.

Secondly, all of the previous declines in house prices locally have been reversed by the RBA entering an easing cycle. Typically when the RBA starts cutting, the market starts to rebound. This time is different for two reasons, firstly with interest rates at 1.5% there is very little scope to cut rates and secondly, the RBA has been very firm on the fact they won’t cut just to save the property market. In addition, recent increases in wholesale funding costs are starting to flow through to “out of cycle” rate hikes from the banks and forced switching from interest only to principal and interest is expected to pick up over the course of 2019 and 2020.

The property market is set in our opinion to have a significant impact on the equity market. If the RBA, APRA and the government can engineer a soft landing then the equity market as whole will be an ok investment. Investors will pick up solid dividends but limited earnings growth. However, it has to be acknowledged the risk of a hard landing is building. The impact in this scenario will be felt broadly with Residential REITs and building companies at the front line. It will spread through the financiers (Banks) who have residential exposures well above international peers (mortgage books equivalent to c. 60% of their assets as opposed to 30-40% globally). It will also impact retail stocks most notably those exposed to furnishing new dwellings (Harvey Norman, Nick Scali, JB Hifi through The Good Guys). We are not sure how this plays out but we do believe the overall market is too sanguine about the risk currently.

Investment Implications

We have no idea when this equity market cycle will end but we do see risks ahead. The US will lead global markets but we believe the risks are more pronounced in Australia where high household debt, a slowing property market and stretched valuations in certain sectors are all prevalent. If the US (or even more importantly China) sneezes, Australia may well catch a cold (or worse still the flu).

Australian Investors need to be aware of these risks and position accordingly, we believe that the following should be some key considerations.

- Portfolios should be more defensively positioned than recent years. Cash levels should be higher and government bonds as well as high quality credit should be considered for their diversification benefits.

- Investors should be more cautious of illiquid assets given the flood of money entering the space and competing for deals. Be particularly cautious of the latest fad of private debt products looking to provide high yields.

- International equities remain preferable to Australian equities. Look to tilt towards Value. We believe that a “risk off” environment will lead to a reversal of the current record outperformance of growth companies.

- In Australian equities, look to limit exposure to financials, residential exposed companies and retail. Look to companies exposed to the boom in infrastructure construction, regulated utilities and quality companies with offshore earnings that are trading at a reasonable price.

Guy is the Chief Investment Officer at Quick Brown Fox Asset Management. Guy has over 13 years’ investment experience as an analyst and fund manager.

Expertise

Guy is the Chief Investment Officer at Quick Brown Fox Asset Management. Guy has over 13 years’ investment experience as an analyst and fund manager.