Hybrid market developments

Since the ASX hybrid markets' all-time record 6.46% flash-crash on Monday, which was triggered by a completely incorrect news report that NAB had bailed-in its NABPC hybrid holders into equity, it has staged an incredible rebound. The Solactive ASX Hybrid Index has now surged 9.2% higher (before franking) over the last three sessions alone...Funnily enough, there has been no media reporting about that.

This should come as no surprise for two reasons. First, as I previously explained here, NAB called and fully repaid its $1.34 billion hybrid (ASX: NABPC), contrary to the report in question, as the major banks have always done with these Basel 3 securities (via repayments, buybacks, exchanges etc).

That meant holders of NABPC were transferred the $1.34 billion in hard cash they expected to receive during the week. Put differently, no NABPC holders were bailed-into equity, and they all received the $100 per unit they had assumed they would get.

Concurrently, NAB also raised $750 million of fresh common equity via an issuance of ordinary shares to an institutional investor, as it did in February 2019 when it repaid one of its $1.5 billion hybrids at that time (Westpac has also done exactly the same thing).

The $750 million of equity raising is a direct benefit to NAB hybrid holders because it increases the buffer of lower-ranking common equity tier one capital that protects hybrids. In particular, Australian bank hybrids are automatically converted into equity if a bank's common equity tier one capital (CET1) ratio falls from the current circa 11% level to a very specific 5.125%. As the banks boost their CET1 ratios, the probability of this risk event falls. Of course, banks also have the option of raising additional equity before they come close to hitting 5.125%, which would be my central case in such a scenario.

Here APRA's stress-tests of bank losses during recessions are informative. In the latest stress-tests that were publicly disclosed, APRA ran simulations that basically involved a much worse version of the last 1991 recession. Specifically, this encompassed:

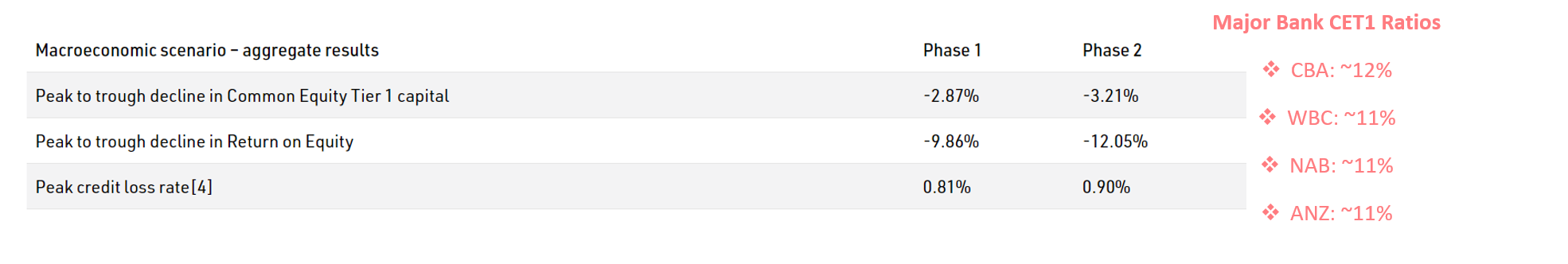

The table below summarises key results from APRA's stress-test. In analysing the results, APRA assessed not only the impact on capital, but also the effects on profitability and loan portfolios. You can see that the maximum CET1 reduction of about -3.2% would only reduce the typical major bank CET1 ratio of 11% today to around 8%, well above the 5.125% trigger for hybrid conversion into equity. This is even after assuming a 35% drop in house prices and an increase in the unemployment rate to about 11%. (Click on the picture to see it better.)

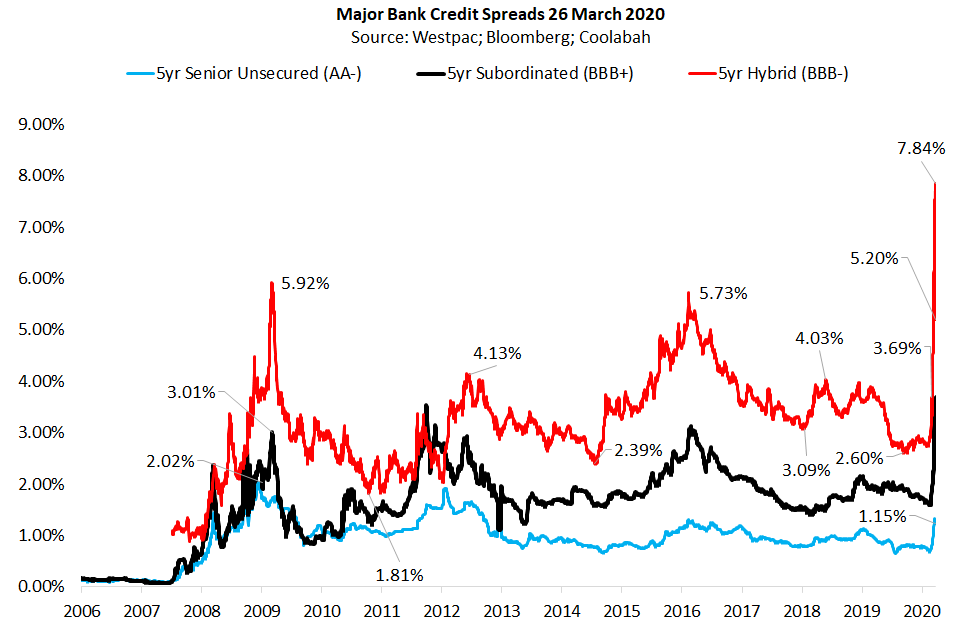

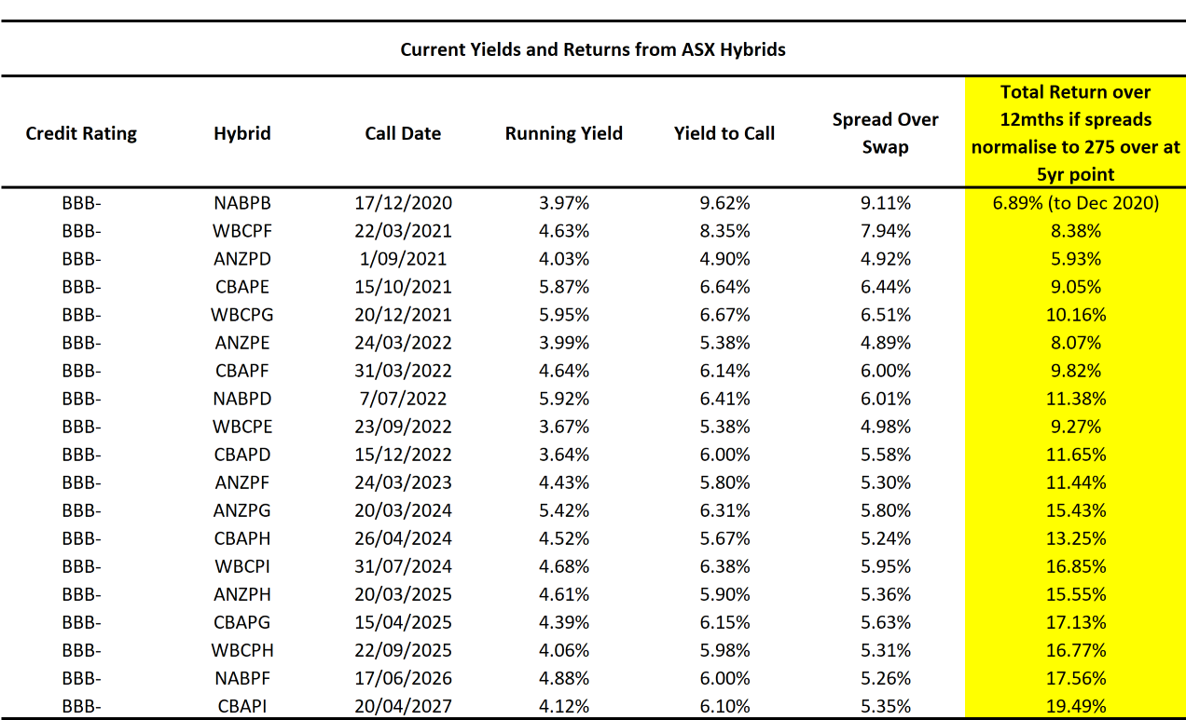

A second reason the ASX hybrid market has been performing so well is because it is historically very cheap, as we previously highlighted. Even after the recent rally, the average 5 year major bank hybrid spread is still at 520 basis points above the quarterly bank bill swap rate, which means it is paying an expected yield to its call date of 5.82%, which is not far off its GFC wides. (In the unprecedented March episode, the spread peaked at 784bps). That is exceptional compensation for an investment-grade, BBB- rated, security.

Since the GFC, Australia's banking system has aggressively deleveraged and derisked, which are positive for hybrid holders. Back in 2007, CBA was more than 21 times leveraged in risk-weighted terms whereas today it is only 8-9 times levered (even after APRA doubled risk-weights on home loans). In 2007 CBA did not have government guaranteed deposits or access to dedicated emergency liquidity facilities at the RBA, which it does today.

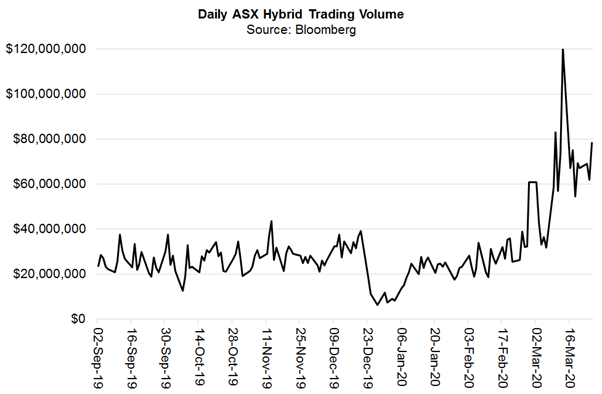

Liquidity, or daily trading volumes, in the ASX hybrid market has also been strong, and around 100% higher than normal volumes. In March to date, average daily turnover has picked up noticeably to more than $63 million a day. On some days, we have seen more than $120 million of hybrids trade, arguably providing much better liquidity than what you find in the over-the-counter, or unlisted, corporate bond market in Australia.

A final noteworthy feature of the ASX hybrid market is that the main ETF, BetaShares' HBRD product, has consistently traded at its Net Asset Value. (My firm, Coolabah Capital Investments, is HBRD's investment manager.)

There has been a lot of debate in recent months regarding Listed Investment Companies (LICs) and Listed Investment Trusts (LITs), including those that invest in foreign high yield (ie, sub-investment grade) bonds and loans. Since the crisis, these foreign high yield LITs have traded at substantial 20% to 50% discounts to their reported Net Tangible Asset (NTA) values.

Over the last 12 months, I repeatedly warned investors that these foreign high yield debt LITs would trade at large discounts to NTA in stress scenarios, as they have always done throughout history, and copped a fair bit of criticism for doing so. Investors in the most recent foreign high yield debt LIT listed in November are currently sitting on 42% losses, underperforming even equities.

This is not because the LIT managers are poor per se---in fact, many are impressive---it is an inevitable artefact of putting illiquid and higher risk assets into a closed-end (as opposed to open-end) fund where (1) the estimates of the NTA are always subject to debate and (2) the closed-end structure forces investors to find a buyer at any price rather than having the manager sell the underlying assets at NTA (if they actually can) as is the case with a normal open-ended fund. One question here is how does one know the true value of these assets if there is limited or no liquidity in them.

HBRD is interesting because it is an ETF that holds ASX listed hybrids that are transparently traded every day. There is no question about the true value of those assets (or the NAV of the ETF) because their prices are signalled every minute of the day.

This contrasts somewhat with many other fixed-income ETFs, which Rodney Lay and others have written about. During the crisis, many global fixed-income ETFs have traded at decent 1% to 6% discounts to NAV.

There are probably two convincing explanations for this phenomenon. First, passive ETFs do not always have dedicated market-makers, and in stress events these market-makers can apparently withdraw their services. (HBRD has an internal market-maker via BetaShares, which is outsourced to an investment bank that is mandated to always provide transparent bids and offers.)

A more convincing explanation for me is that most fixed-income ETFs are holding unlisted OTC corporate bonds. The NAVs associated with these unlisted corporate bonds can be difficult to estimate when liquidity dries up, which is a problem that has plagued the non-financial corporate bond market over the last month.

It has been much less of a problem in bank-issued financial (as opposed to corporate) bonds that can be sold to central banks under repurchase (or repo) arrangements, which benefit from structural demand for these assets through the liquidity books of bank balance-sheets, amongst other investors.

If the NAV of a corporate bond ETF is stale or mis-estimated, one can expect a rational discount to NAV to emerge during periods of stress when investors question what the true NAV actually is. That is, the actual trading price is a form of price discovery that can lead the reported NAV when the underlying assets are illiquid.

The same insight applies to fixed-income LITs that hold illiquid assets. While part of the explanation for the discount to NTA may be the closed-end structure, another is very likely price discovery where investors are rationally discounting the reported NTAs because they are stale due to the difficulty of estimating true value when dealing with thinly traded or completely illiquid assets.

1 topic