Is Australian monetary policy tight enough?

There is key evidence that monetary policy has not been sufficiently tight. Comparing the cash rate to the policy setting suggested by various ‘rules’ that summarise past central bank practices and the stance of policy in other countries suggests the RBA policy setting has been too easy. Maybe we are witnessing an immaculate disinflation but assessing the level of the cash rate suggests there are significant risks to the disinflation path and interest rate outlook.

Inflation has slowed substantially from a peak of around 8% at the end of 2022 to around 4% at the end of 2023. But much of this decline came from an unwinding of pandemic-related supply, shipping disruptions, and the energy price spike from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, not monetary policy.

Given that the maximum contractionary effect of monetary policy on inflation occurs after around 18 months, we haven’t yet seen the full effect of contractionary monetary policy. The economy has slowed but the easing of the tight labour market has been very mild to date.

Various factors continue to contribute to high inflation, including large increases in the public sector, minimum and award wages; tax cuts in July; the tight housing market and weak productivity growth. Just a couple of weeks ago, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) pointed to the “potential need for further monetary tightening to achieve the targeted inflation range by 2025” (IMF 2024a).

Policy rules

Policy ‘rules’ are widely used in central banks and academia to describe how the central bank has in the past, or should, set the policy interest rate based on inflation and ‘spare capacity’ (i.e., the unemployment rate or a GDP ‘output gap’) and the neutral interest rate (i.e., the rate that is neither stimulatory nor contractionary).

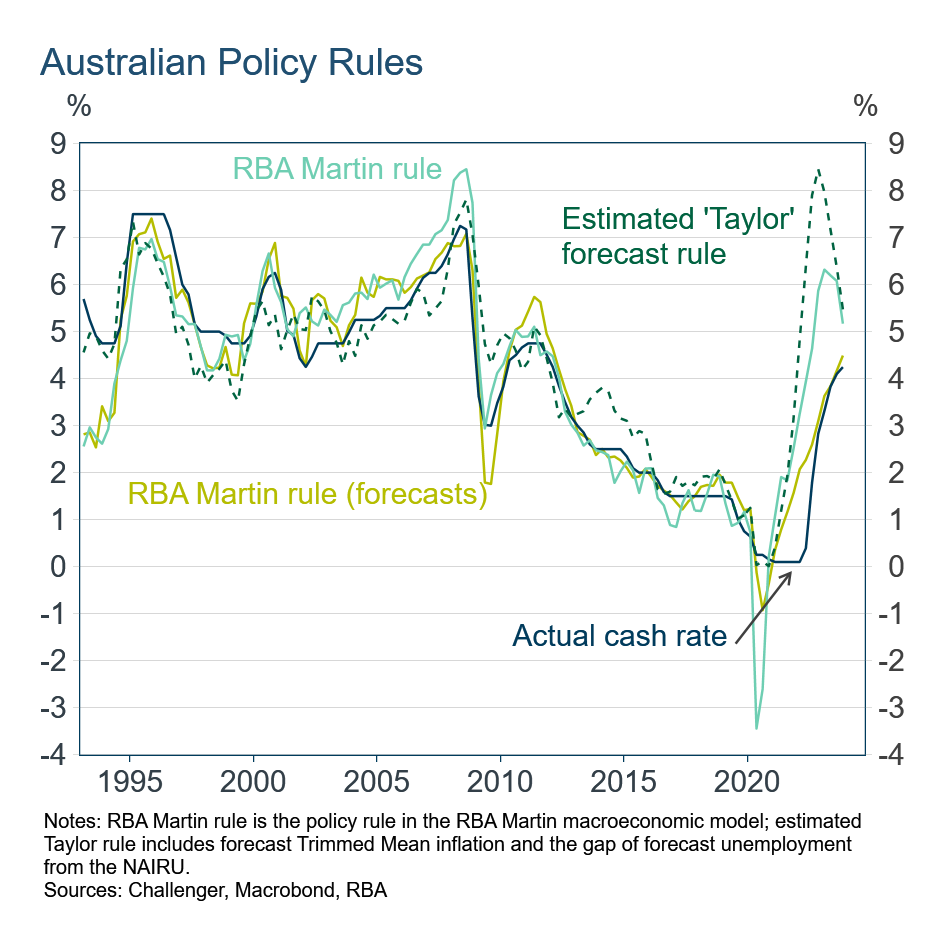

The policy rule in the RBA’s macroeconomic model, MARTIN, and an estimated (‘Taylor’) rule (based on forecast inflation and unemployment) indicate the cash rate should be over 5% (Figure 1). A Martin rule using forecasts would have the cash rate around its current level, but all three rules indicate the RBA should have started tightening well before it did, suggesting the RBA is playing catch-up to bring inflation back to target.

Figure 1: Different rules and where the cash rate would be if those rules are followed:

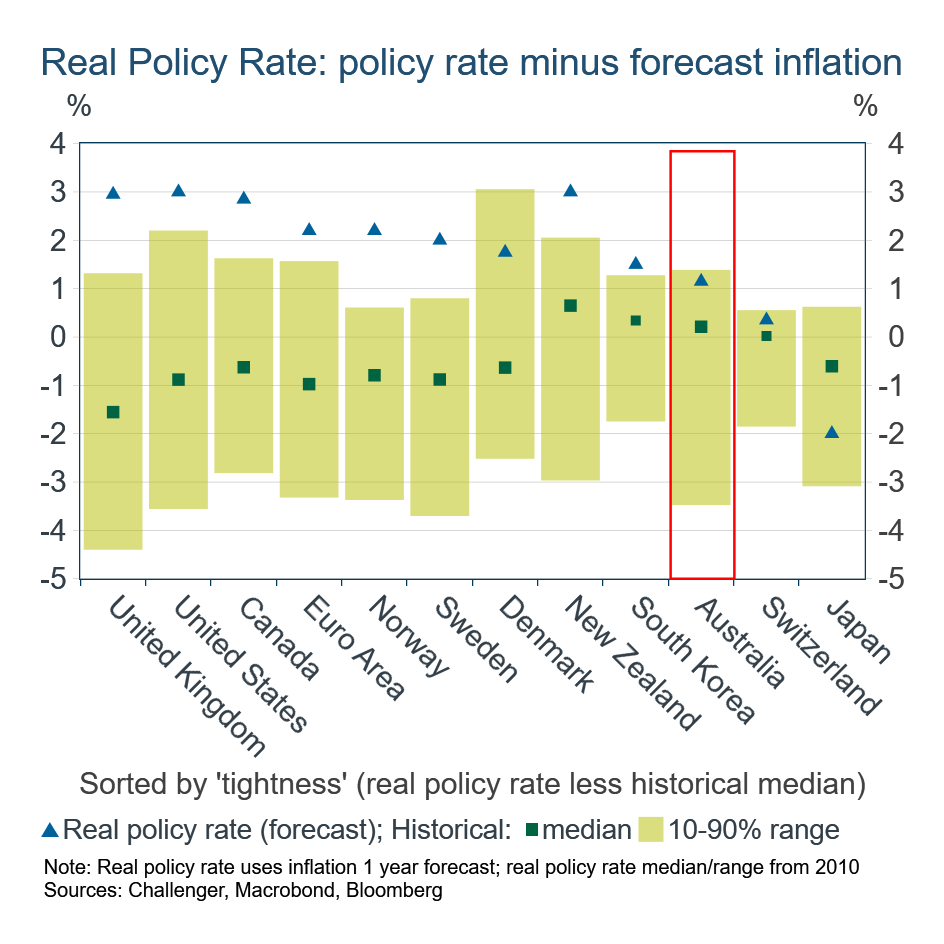

Figure 2: The real rate

International comparison

To represent the true return to saving (or cost of investing) we need to adjust the interest rate by how much prices change. In the same way, to assess how tight monetary policy is we should adjust the central bank rate for (realised or forecast) inflation, i.e., use the real policy rate. The increase in central banks’ real policy rates has been much less than the increase in their nominal policy rates because of higher inflation.

Monetary policy in Australia is less restrictive than in most other advanced economies, with a lower real policy rate both in absolute terms, and relative to its historical average and range (Figure 2). A less restrictive policy stance in Australia does not appear to be justified by economic conditions.

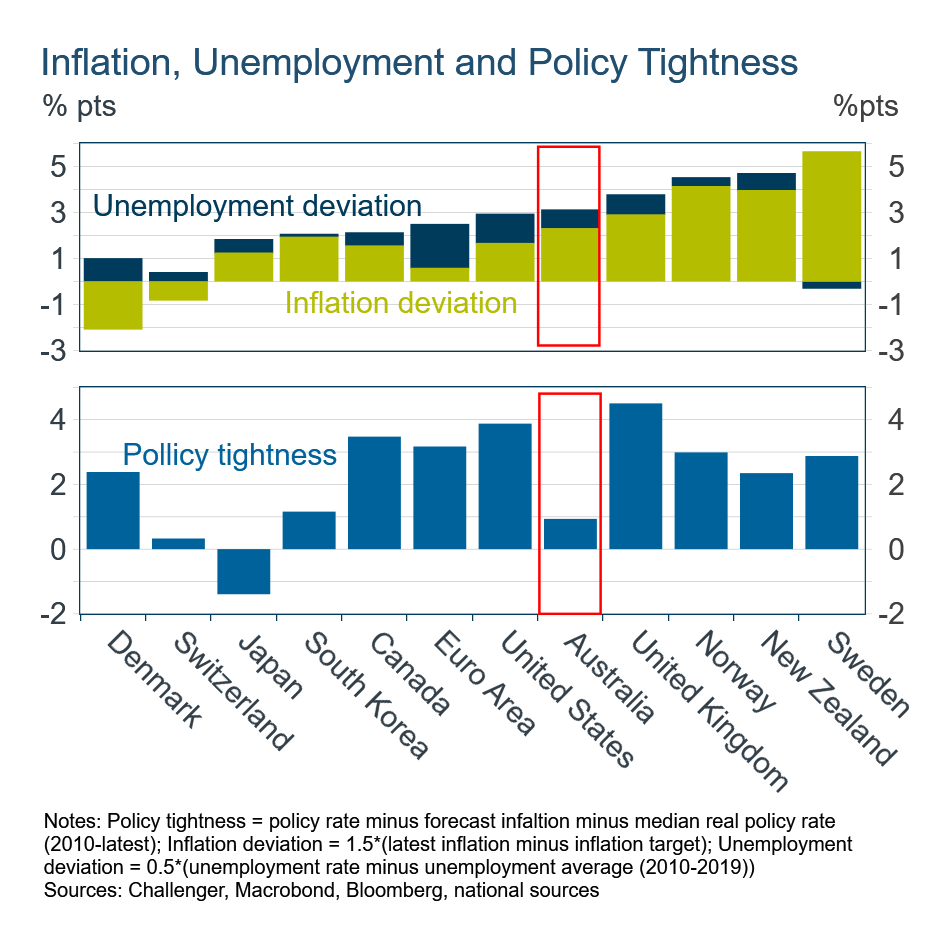

Figure 3 ranks countries by the sum of their inflation deviation (forecast inflation minus the inflation target) and their unemployment deviation (unemployment rate minus average unemployment before the pandemic). This macroeconomic deviation for Australia has declined but is still in the top half of countries despite policy here being less restrictive. The US, Euro area and Canada have all tightened much more given their macroeconomic situation and so have better prospects of containing inflation.

Figure 3: Inflation, Unemployment, and Policy Tightness

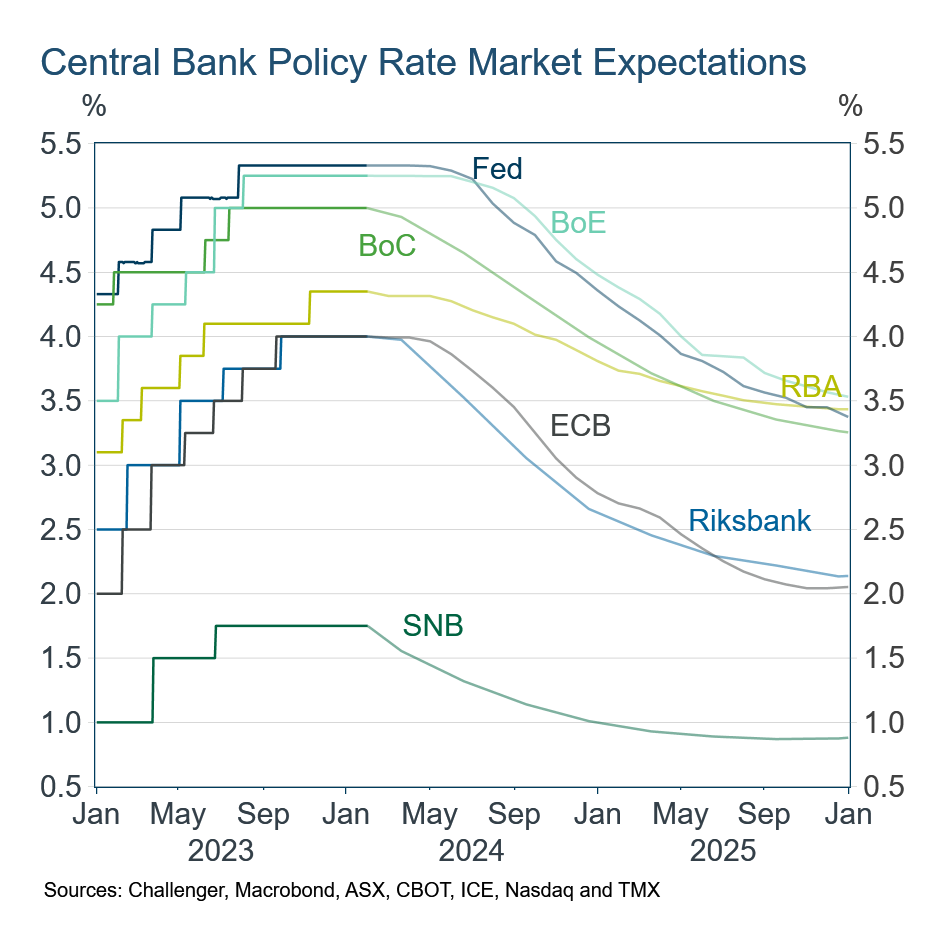

Figure 4: Rate Expectations

Discussion

From one meeting to the next, market analysts consider whether new information is cumulatively positive or negative and so whether the cash rate is likely to be held constant or increased or decreased (hoping to mimic the RBA Board’s thinking). But it is important to look not only at changes and consider whether the level of the cash rate is correct, otherwise, a policy setting error can persist.

The question the RBA Board should be asking on Tuesday is whether policy is tight enough.

A comparison of historical policy settings in Australia and relative to other countries suggests the cash rate has not been high enough. RBA communication has indicated it is placing a large weight on minimising the increase in unemployment.

This is a worthwhile aim, but less weight on inflation carries the risk that inflation remains above target for too long with inflation becoming ingrained and sticky above the target.

Persistently high inflation will necessitate high-interest rates for longer. Not surprisingly, this is exactly what financial markets expect, with the RBA projected to have a higher policy rate than other economies by the end of next year (Figure 5).

But given the evidence that policy has not been tight enough in Australia, there’s a good chance that the scenario of internationally high Australian interest rates plays out sooner than that.

2 topics