Is value investing really dead?

There is strong support from many decades of data that investing in value stocks - lowly-rated companies that are deemed undervalued compared to their future worth - can deliver strong outperformance. However, in the past few years, compared with market indices increasingly dominated by bond proxies or tech stocks, value style portfolios have underperformed.

In fact, growth investing has outperformed value investing for so long now, some are beginning to wonder if it will ever end. 2020 has been an extremely difficult year for value investors, and it comes after a five-year period which could hardly be described as vintage for the investment style.

At the turn of the year, the relative valuation dispersion between value and growth across global markets was reaching the widest in history, which we firmly believed was unsustainable. Fast forward eight months and as global markets have reacted to the impact of Covid-19, this dispersion between value and growth has widened further. It is now at all-time highs rivalled only by the extremes witnessed before the tech bubble burst in 2000.

While the saying goes that history doesn’t repeat itself, but often rhymes, there are some startling similarities between the market today and the market back in 2000.

Growth companies, especially those in the technology sector, had outperformed dramatically, driving the Nasdaq to all-time highs. Many argued technological disruption had changed the rules of the game and we had entered a new paradigm for equity markets where fundamental valuation no longer mattered. Anyone with a preference for the cheap, old economy stocks were deemed as investment dinosaurs, destined for extinction.

Does this sound familiar?

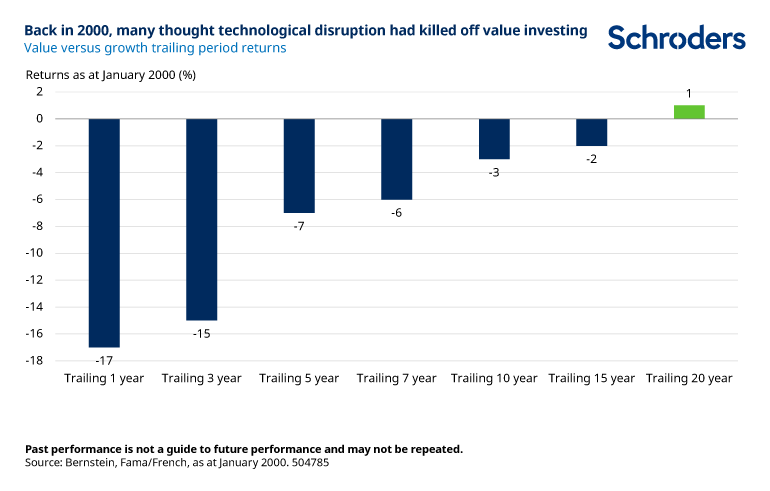

The chart below shows the contrast in fortunes between growth and value investors at that time. In January 2000, value was not only trailing growth materially across shorter time horizons, it had also fallen behind over 10 and 15 years and was only just ahead on a rolling 20-year basis.

Needless to say, you could find a lot of obituaries being written for value at this point.

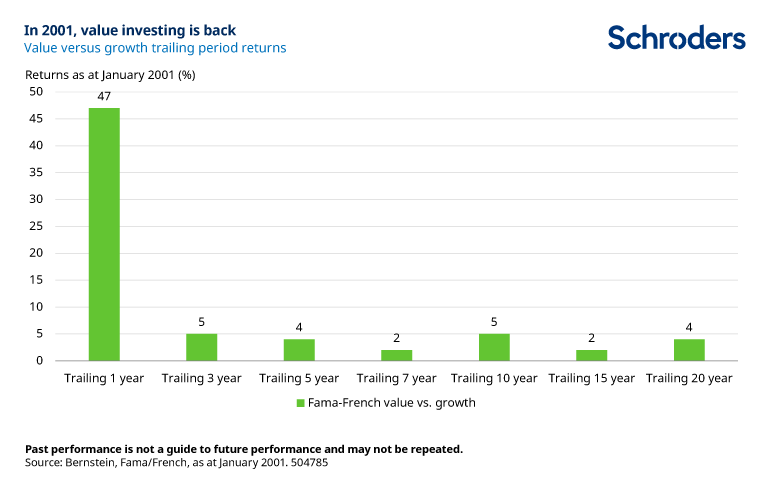

Just 12 months later, however, the situation had completely reversed. Come January 2001, value had regained the upper hand across every single rolling time period.

After years of pain for value investors, service had been resumed for those who had kept faith through those very difficult times.

The example from the dotcom era is a stark one, but it is not a timing message. Nonetheless, when markets are all pointing the same way, history tells us it often ends in significant pain for those that have put all of their eggs in one basket.

We do not profess to know when the tide will turn, only that we believe the ongoing and increasing disregard for company fundamentals is unsustainable.

In the early 2000s, it turned out the world had not really changed as much as people imagined and valuation still mattered – it mattered a great deal. We remain absolutely steadfast in our belief it matters every bit as much today.

Is value dead? Well, people have thought so before and you do not have to go too far back in time for an example of when they were proved wrong – and at a pretty lively pace too.

Are today’s growth companies just “better” and value companies just “worse”?

One counter argument to the comparison between today and the tech bubble is that today’s technology companies justify their valuations because they are simply better companies, with better earnings profiles in markets that still have significant structural tailwinds.

The narrative also goes that today's value stocks are poorer quality than historically, with far greater cyclicality and significant structural headwinds.

When we take a step back and look at the empirical evidence for this narrative, we see no evidence of this in the data.

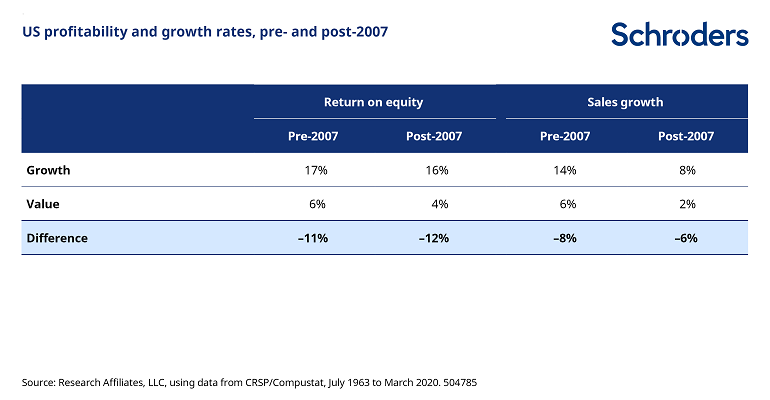

Research Affiliates have looked back through history of the US stock market to assess the return on equity and sales growth rates of growth and value companies over time. The data below shows that between 1968 and 2007, value companies’ return on equity lagged growth by 11%. Since 2007, this has only deteriorated very marginally. To justify today’s valuation dispersion we would expect to see a far more distinct difference.

On sales growth, the difference between value and growth has actually narrowed, favouring value.

So to say that today’s growth is better and today’s value is worse is simply not supported by data.

While this data is backward looking, many argue the prospects for technology stocks are brighter given they can exert greater monopolistic power and take an increasingly higher share of profits. Is it this that can justify the disconnect between value and growth?

One way to test this is to try and account for those large monopolistic shares by cutting the universe a number of ways: exclude the TMT (tech, media, telecoms) sectors that they operate in; exclude the largest 5% of companies by market cap; or exclude the most expensive 10% of shares. Even after doing all of this, you still see the same level of relative valuation dispersion between growth. So none we believe are explanatory variables.

That arguably leaves us with one explanation… it’s just a story. And as any behavioural psychologist worth their salt will tell you, humans fall in love with narratives and the market is in love with growth today.

The scariest times can often yield the best rewards

While past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance, history suggests that the best time to buy (and also the worst time to sell) has often been after sharp pullbacks in relative performance. The biggest rewards can come from being brave during the scariest times. For investors willing to ride out the turbulent times, the potential rewards could be considerable once the tide turns.

Access unloved stocks with long term growth potential

We seek to identify stocks which trade at a substantial discount to their fair or intrinsic value and where profits growth will surpass expectations. To be the first to read my latest insights, hit the follow button below.

1 topic