Markets haven’t changed: prices still move more than business value

For decades, the prevailing academic narrative has been that public markets should become progressively more efficient, more accurately reflecting the underlying value of the businesses that the share prices represent.

Information now moves, quite literally, at the speed of light. Algorithms trade in microseconds. Vast pools of capital and armies of analysts research and analyse companies in real time.

All of this should mean that share prices trade within a tighter range of the company’s underlying value.

Yet when you look at how share prices actually behave, the evidence points in the opposite direction. Markets do not look more rational nor more anchored to fundamentals. If anything, they look more reactive, more flow-driven, and more vulnerable to swings in sentiment than they did a generation ago.

What Does The Data Tell Us?

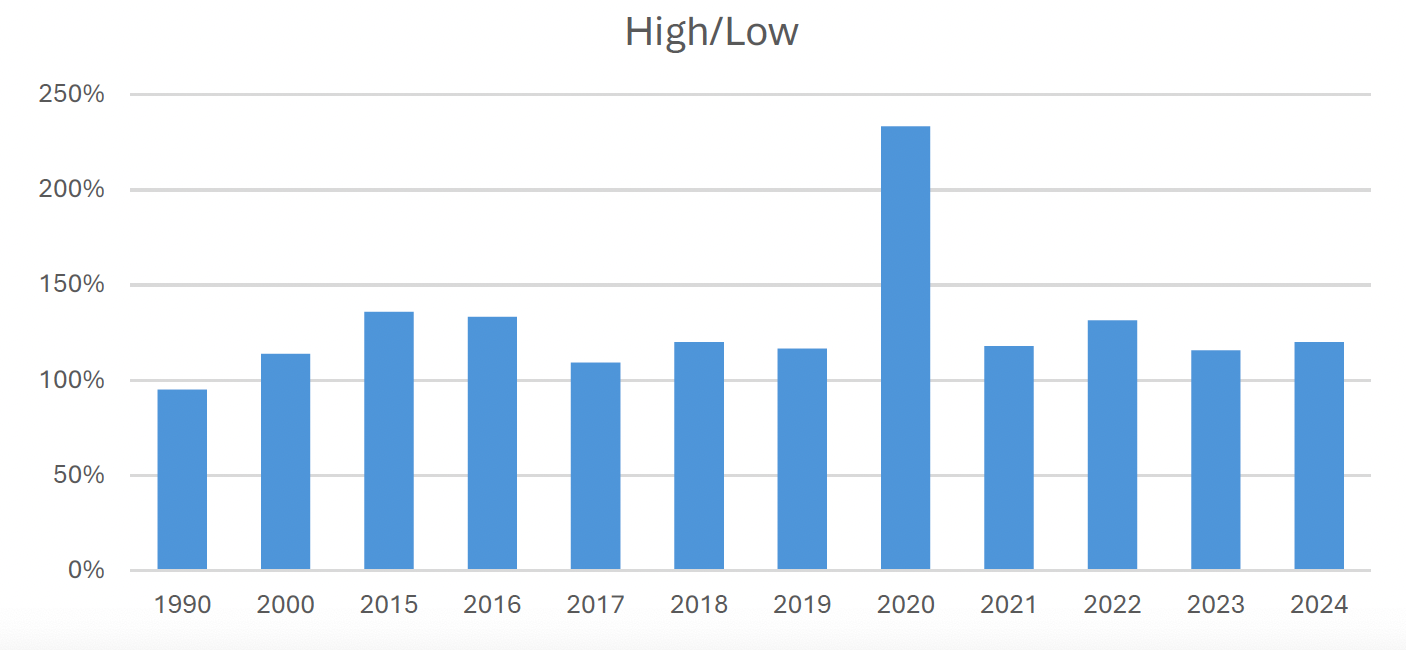

A simple, intuitive way to see this is to look at the median ASX-listed stock’s 52-week high versus its 52-week low. This is a rough gauge of how much the market’s view of a company’s worth fluctuates over a single year.

Over more than 30 years worth of data, the picture is remarkably consistent: in a typical year, the median stock on the ASX trades at a high that is more than double its low.

In other words, the “average” company experiences an annual peak-to-trough price swing of greater than 100%.

The consistency of that pattern over a long time frame is what matters. It tells us that share prices today are at least as volatile as they were in the early 1990s, despite enormous advances in technology, disclosure and professionalisation. Unless we believe that the underlying businesses themselves have become twice as volatile in their true economic value – a hard case to make – then it follows that markets are no more efficient at pricing businesses today than they were three decades ago.

Ideally, we would compare price swings directly to changes in intrinsic value, defined as the present value of all future free cash flows a business will generate from now until judgment day. But that isn’t practical with any precision. Instead, we need to rely on imperfect but relevant proxies that capture how the typical business is evolving over time in an effort to be “roughly correct.”

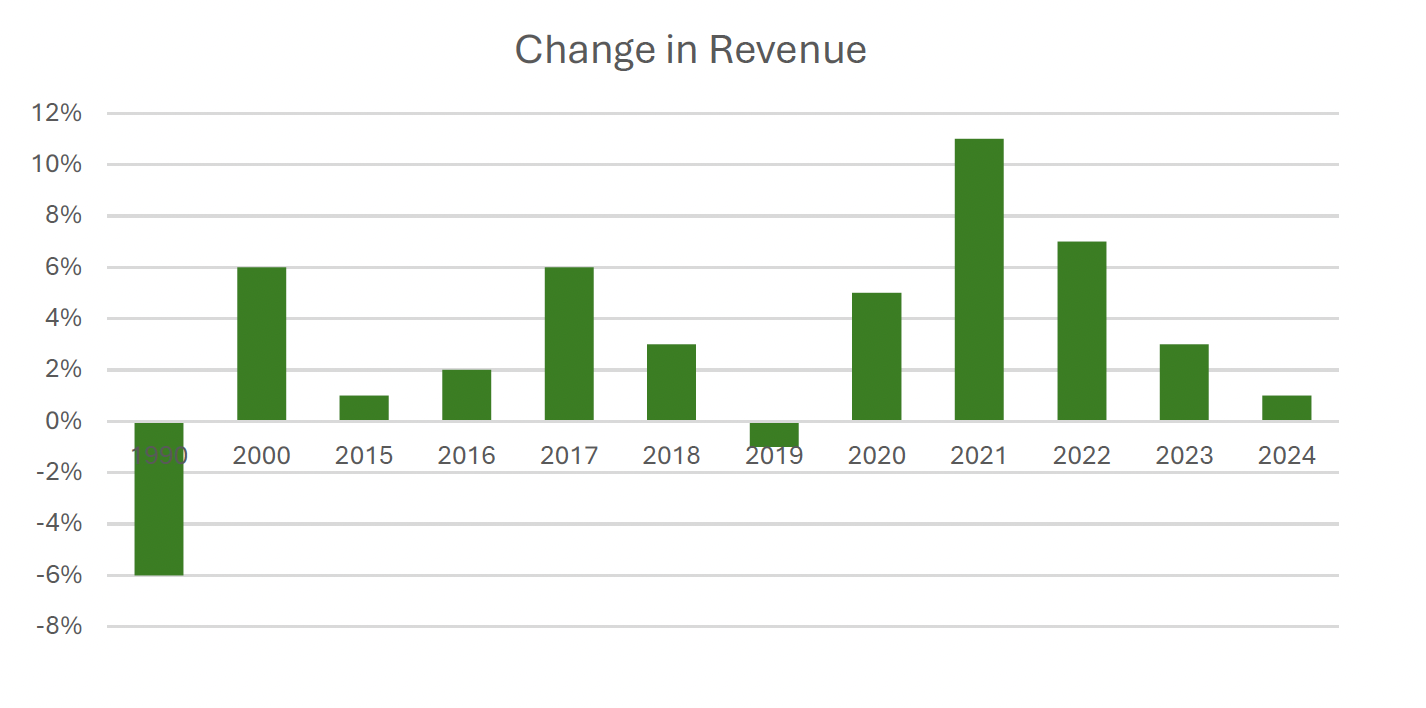

Reasonable candidates include book value per share, earnings per share, and revenue. Each has limitations: earnings can be noisy and subject to accounting judgements; book value can be distorted by write-downs, acquisitions or capital-light models. Revenue, by contrast, is harder to manipulate and provides a clean read on whether the median company is broadly shrinking, flat or growing. It is not a perfect representation of value, but it is a useful, relatively unambiguous yardstick.

If we start with revenue and apply some normalising assumptions for the median business – say, a 60% gross margin and a 10% EBITDA margin – then a 1% change in revenue will translate into roughly a 6% change in EBITDA. In our data set, the median company’s revenue moves in a band of approximately -6% to +11% per year. That implies that EBITDA swings in a range of roughly -36% to +66%.

Of course, in reality, short term swings in earnings have relatively little impact on the long term valuation of a business. But even using this extreme framing, the annual movements in price still exceed the movements in value, and frequently by a wide margin.

From that we can come to one very clear (and potentially very profitable) conclusion:

Stock prices consistently move more than business value.

While some would argue markets have become larger, more rational and better at accurately pricing businesses, we’d instead argue they’ve become louder, more emotional and prone to consistently present opportunities for the rational investor.

The Old Patient Bear Wins in the End

A quick story.

The young bear charges up and down the river, splashing around and lunging at every flash of silver. Sometimes it will catch a fish, often it won’t but it always burns an enormous amount of energy in the process. Its days are volatile: big wins, big misses, lots of decisions and activity.

The old bear has seen many seasons.

It knows the river, the currents and the narrow channels where salmon are funnelled or forced to jump. It walks to a particular rock or stands just below a small waterfall and waits. For long stretches it appears to be doing nothing at all. Little activity, few decisions, patience.

Then, when a salmon passes through its high-probability zone, it moves, decisively. Over a season, the old bear often ends up just as fat (if not fatter) than the young one, but with far less wasted effort and risk.

We try to be the old bear.

We stay within our spots, we know exactly what we’re looking for and we remain patient. We know that patience often gets you to your destination faster than haste and activity for activity's sake does anyway.

We don’t react to prices. We don’t trade daily. We don’t focus on short term market movements or things that are out of our control.

Our time is spent researching good quality businesses, maintaining our watchlist, meeting management teams, talking to customers and slowly but surely building conviction in our investments and a pipeline of new ones.

Our brokers don’t always love us for it, but we can go many weeks without any meaningful activity within the portfolio.

On the outside, this might look like inactivity. But it is preparation for when the increasingly irrational markets present an opportunity right in our sweet spot.

When that opportunity does present, we move in a way that matters.

Every so often, like is occurring today, markets can switch quickly from exuberant optimism to fear of loss. Some stocks, albeit many of them coming from silly valuations, are already -30-50% from their highs set just a couple of months ago.

Good quality businesses can trade to ridiculously cheap valuations whether due to market or company related short term issues, or a combination of both.

But good quality business don’t remain cheap for long. The market might be irrational for short periods, but eventually, it gets it right.

Whether it was Praemium (ASX:PPS) at 40c when the market dumped the stock in 2023 after a short term profit impact. Or Cogstate (ASX:CGS) last year at 90c when Eisai dumped stock unexpectedly in the market. There have been many others, and the data suggests there will be many more.

Good businesses that have long term track records of profitable growth, and bright long term outlooks, frequently go on sale for short periods.

And it is the preparatory work, the knowing exactly where to sit and wait for the fish to swim, that allows us to move quickly and meaningfully in those times that opportunities present.

It is easy to be drawn in by the noise and flashing lights of modern markets. To react to every price movement or macro development.

But it is more profitable to recognise that today's market consistently throws up opportunities for those that are ready and know where to wait.

Be the old bear.

5 topics

2 stocks mentioned