Oracle: why a 40% surge is just the beginning

When a stock like Oracle (NASDAQ: ORCL) skyrockets 40% in a single day, it’s easy to get nervous.

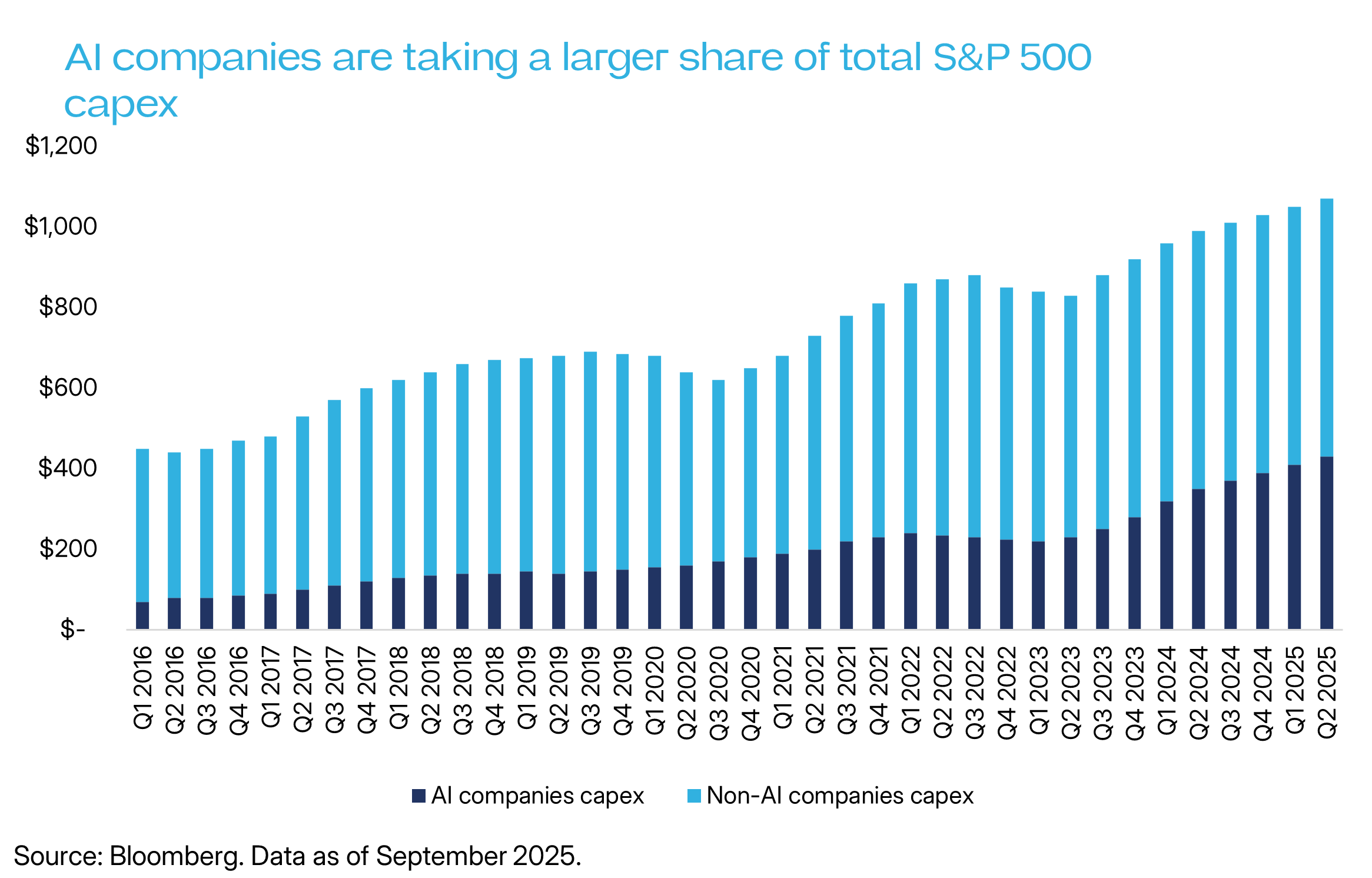

Critics are already out in force, calling the AI boom a bubble: a closed loop where Nvidia, Microsoft, and Oracle just sell things to each other. They point to the colossal spending (capex) and ask, "where's the revenue?"

But the critics are missing the forest from the trees. Oracle isn’t caught in a bubble; it’s running one of the oldest and most lucrative plays in American capitalism.

Capex: the “land grab first, rent later” playbook

For centuries, US capitalism has followed a pattern: grab land first, then charge rent on it second.

This involves massive upfront investment, offering the old “silver-or-lead” dichotomy to competitors, and then, only at the end, outsized profitability.

Some examples from history:

- The railroads: Robber barons like Leland Stanford poured colossal sums into laying track, bankrupting rivals and creating monopolies that later became enormously profitable.

- Standard Oil: John D. Rockefeller didn’t just drill wells; he controlled the refineries and pipelines. By dominating the middle of the supply chain, he could dictate terms to the entire industry.

- Amazon: Jeff Bezos famously ran Amazon at a loss for nearly two decades. Profitability was delayed until scale and dominance were secured.

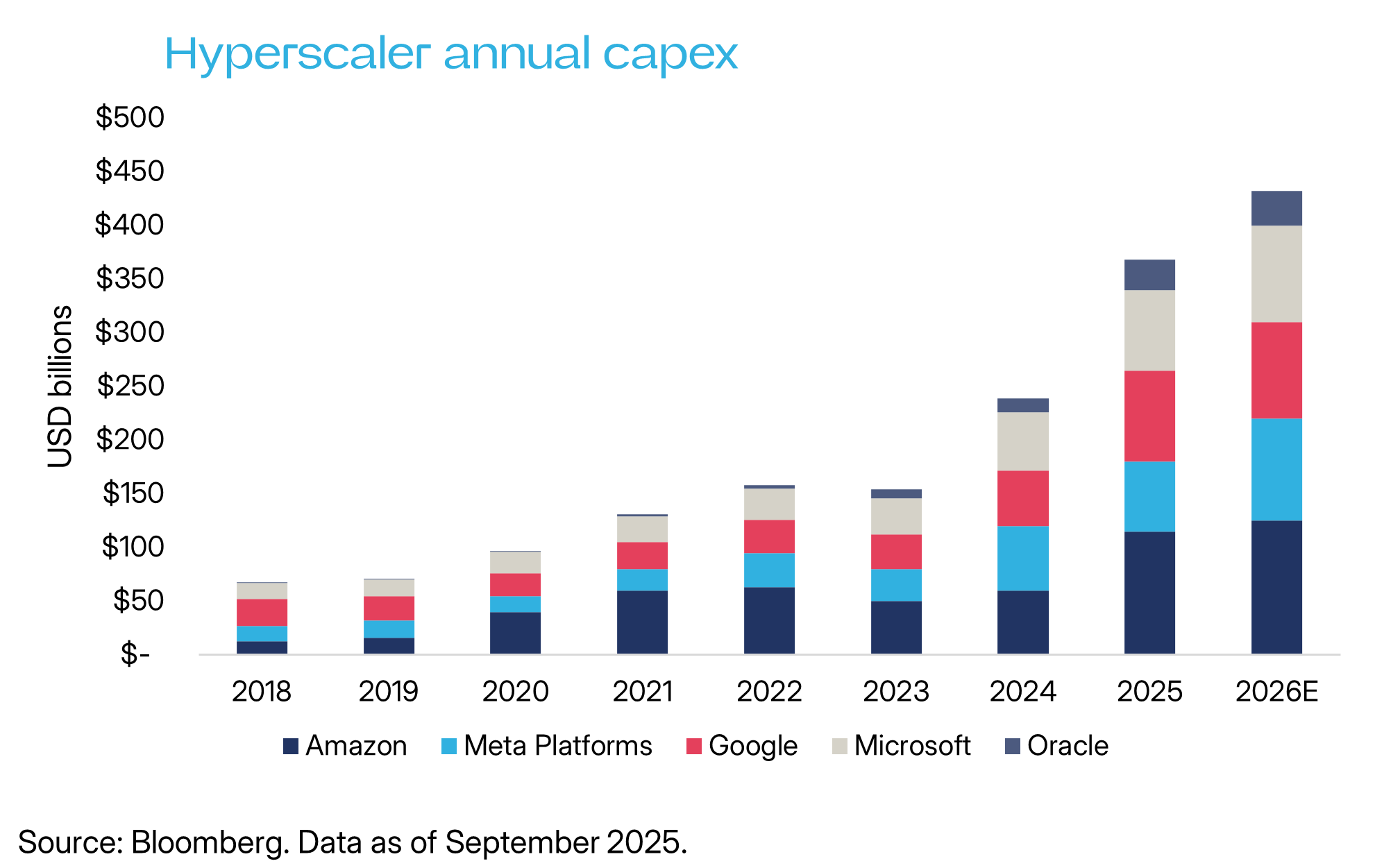

The spending spree by Oracle and the hyperscalers (Google, Microsoft, Meta) fits neatly into this tradition. Oracle alone committed $35 billion in capital expenditure this fiscal year to build data centres for the AI era. Far from a weakness, this is the cost of admission for grabbing prime real estate in what Larry Ellison calls a “gigantic, multi-trillion-dollar market.”

Revenue: the real metric of success

In a growth phase, revenue - not profits - is the ultimate yardstick. Companies can manage margins later, but capturing market share and customers comes first.

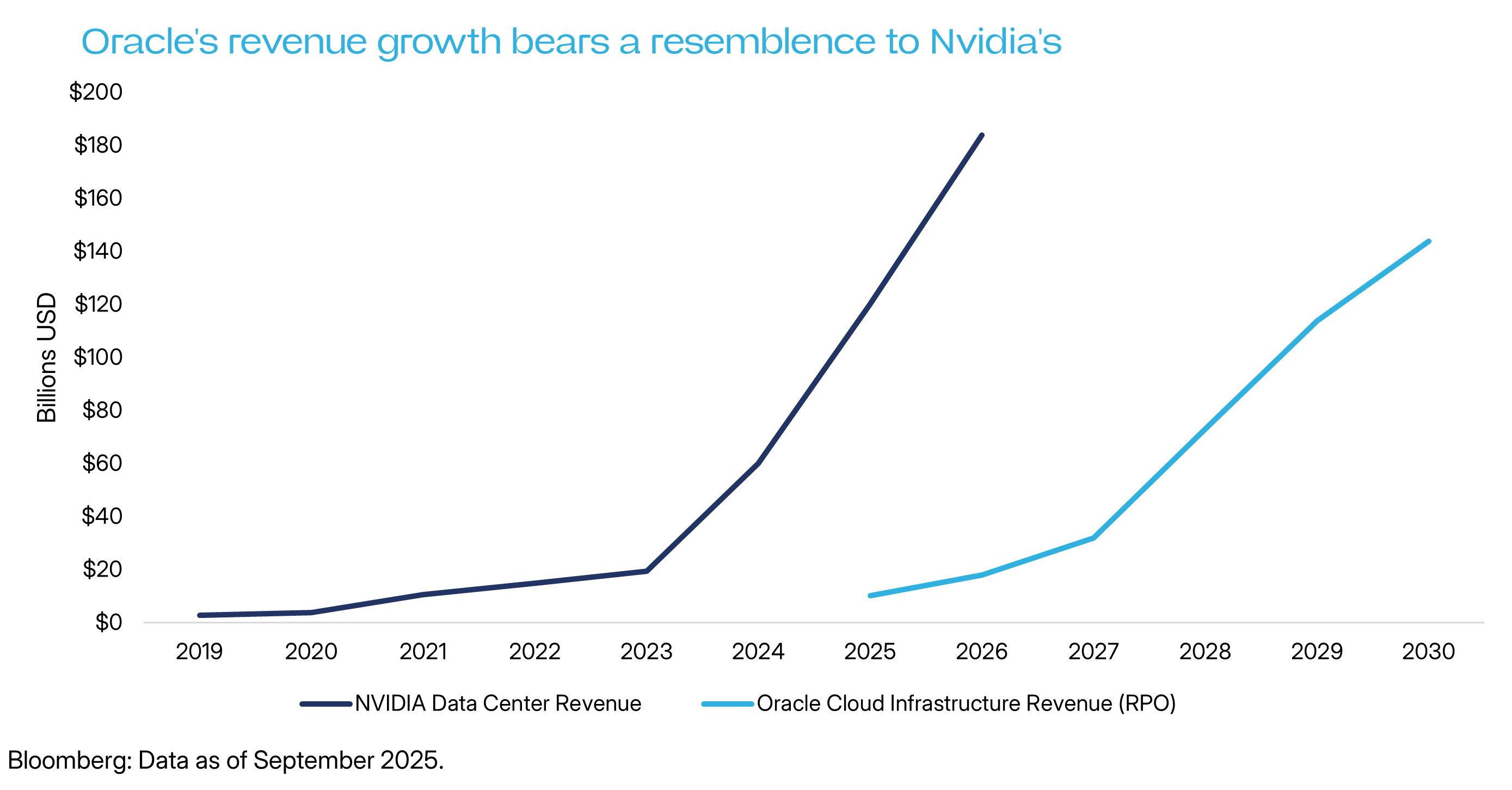

Oracle’s revenue pipeline is extraordinary. The company recently reported $455 billion in Remaining Performance Obligations (RPO) up 359% from a year earlier, Most of this came from OpenAI, creating something of a halo effect as well. RPO is contracted legally binding future revenue that has not yet been billed. For perspective, $455 billion is nearly double the annual revenue of JP Morgan.

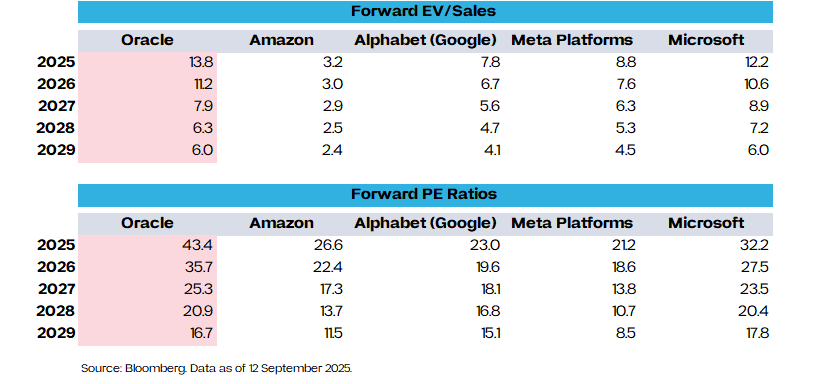

CEO Safra Catz reinforced the story on Oracle’s latest earnings call, noting that several large deals closed at quarter-end and that “many, many more are in the pipeline.” She expects AI demand to keep pushing sales and backlog “even higher.” The stock’s rally isn’t irrational exuberance: it’s the market rationally pricing in visible, contracted, and still-growing business.

A long runway for growth

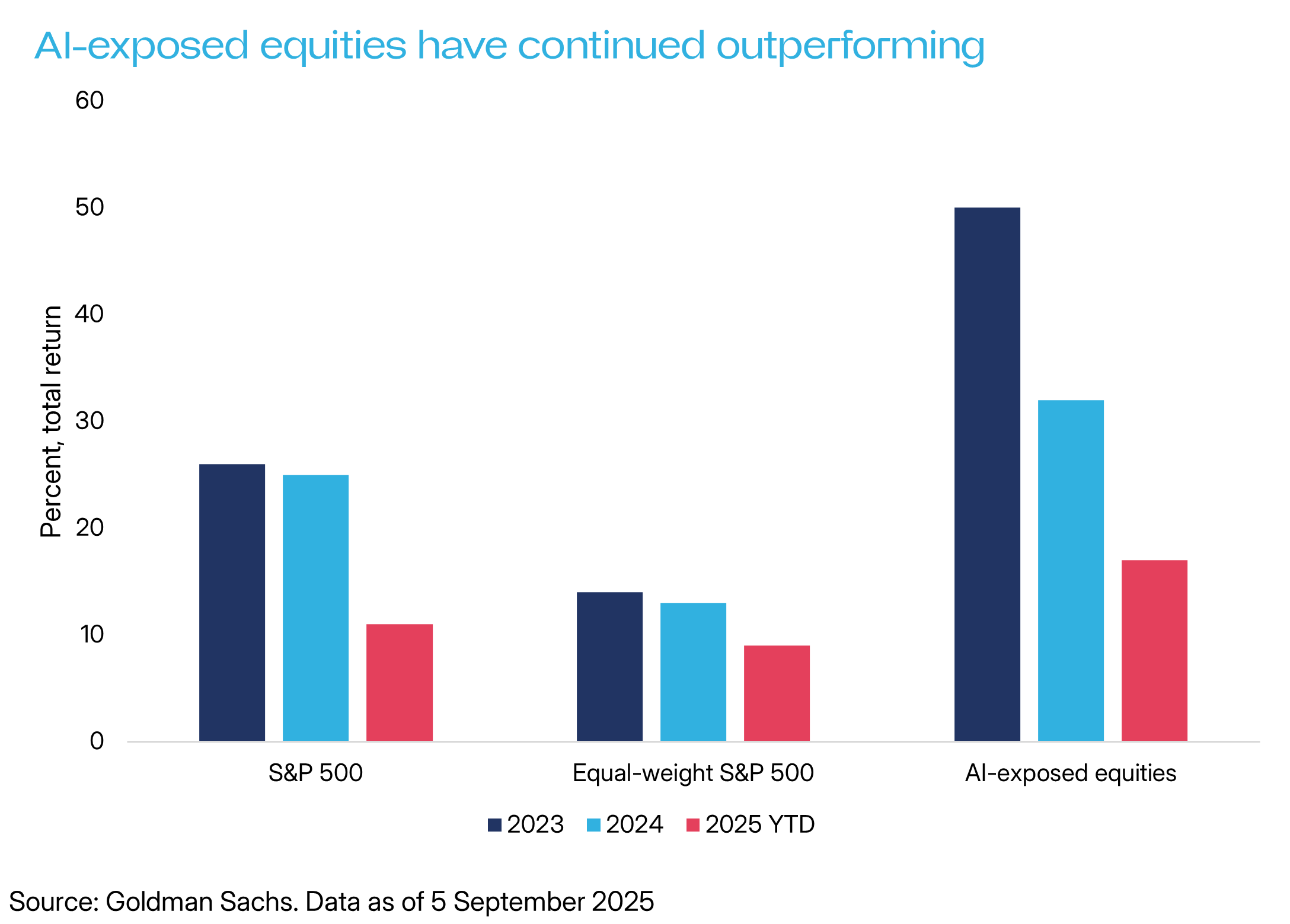

There is a lot of retail hype, sure. But we’re still in the earliest innings of the AI cycle. ChatGPT only launched in late 2022, and adoption remains at an experimental stage. Few companies are paying for AI services at scale, and very few are reporting meaningful bottom-line impact.

That will change quickly. Competition ensures it. Once AI-powered productivity tools deliver proven efficiency gains, companies won’t be able to stand still. The gap between adopters and laggards will widen dramatically, forcing investment.

We’ve seen this playbook unfold before:

- In the late 1990s, websites shifted from novelty to necessity.

- A decade ago, cloud migration was a choice; today, it’s table stakes.

AI is following the same trajectory. Once adoption reaches a tipping point, demand will surge, driven not by hype, but by the cold logic of survival in competitive markets.

Oracle, with its $35 billion capex build-out and $455 billion in contracted revenue, is positioning itself as one of the landlords of this new digital economy. Far from irrational, Wall Street’s enthusiasm reflects a sober reading of history: first comes the land grab, then comes the rent.

About ETF Shares

ETF Shares is a low-cost index ETF issuer, based out of Macquarie University. We specialise in Magnificent 7 and US technology ETFs.

3 topics

1 stock mentioned