The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind

Global Macro

How good are you at reading people? How about a large frightened animal? It’s an interesting question, in today’s tech driven social world, to consider the skill of “reading” the situation. Is it being lost? Does it matter? Hold that thought, and consider the following. You are asked to step in a 20 metre wide fenced enclosure, with a horse kicking and galloping at full speed around the perimeter.

Your task. Get the horse to “join up”. Huh? Get the horse to calm down, accept you as the leader, walk over to you follow where ever you walk like a puppy dog. Oh, and you can’t touch the horse.

I had no idea that could be done. But it is all about “reading” the horse, and then sending the horse the right signals. You see, horses are herd animals. Meaning they like to stick together, and they like to have a leader. When they get a fright they bolt. Typically for some 400 metres. And then they look to calm down, to re-join the herd, to find a leader. You simply have to recognise this, and present yourself as the leader. Easy right?

Well yes actually. When you know what to do. The horse will give you signs it wants to calm down and look for a leader. It will slow down. It will lick its lips. It will flick its ears to listen to you. It will snort. You show some leadership by getting in front and changing its direction a few times, then turn away (at the right time), and hey presto, it walks up and follows you. Like a puppy dog.

Like horses, markets sometimes “take fright”. I’m not suggesting I can step in and lead the market. Far from it! But I can try and read it. What caused it to jump, what signs are there that it is calming down, and so on.

And certainly the worst December for US equity markets since 1931, followed by the best 2 month start to a year since 1934, would present as a market that “took fright”.

So what now? Is the market calming down? Or is the “scare” still there?

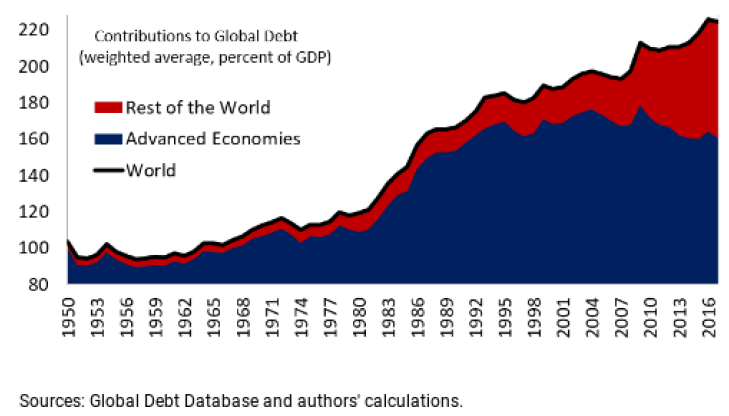

We have been writing about the “scary” situation since June. Specifically, was the world about to pay the price for 10 years of zero interest rates and a blow out in global debt to 185 trillion dollars, aided by 18 trillion dollars of purchases by the G4 central banks plus China?

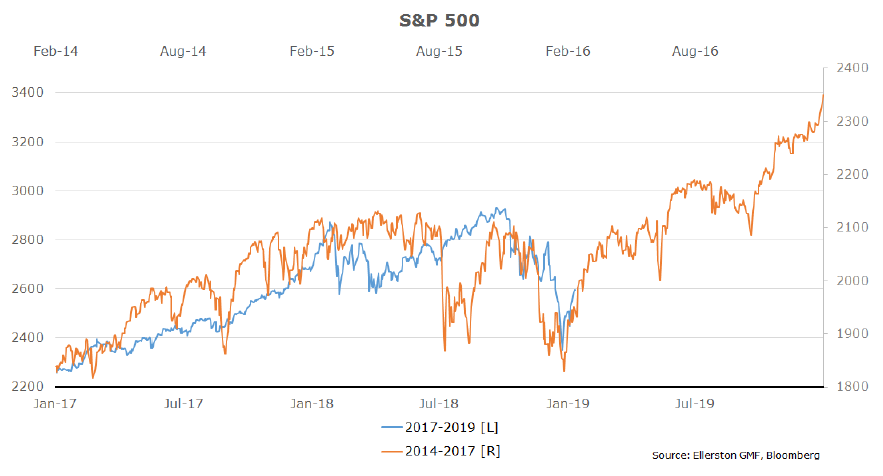

But we also speculated in January that the Fed pivot had removed that “scare”, at least for now. Could it be that Q4 18 was “just” a healthy market correction,

touched off by tariff wars and Fed hikes, and with that behind us we are now in for smooth sailing? Like 2016? The horse is calming down?

The answer, my friend, is blowing in the wind. At least that might be Bob Dylan’s answer. For me, it is as always, somewhere in between. (At least that’s how I sing it).

So this month, let me put the pieces together for you so we can at least be ready for what is next. Or possibly next.

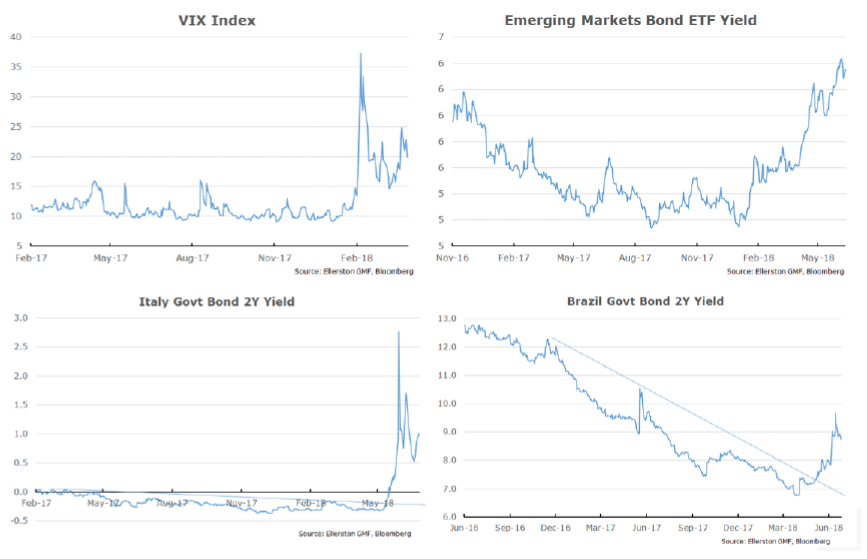

Last year we wrote about wage and inflation pressures building in the US, and that the Fed would have to hike rates every quarter to slow the economy. At the same time, we were concerned about the “credit bubble”, the dramatic increase in money invested in risky bonds around the world, in search of a higher yield. And what would happen if the lenders of this money got nervous and wanted it back.

The first, for us, was relatively easy to track and forecast. The second, however, is like predicting when a horse will take fright. Sometimes obvious, but many times a trivial catalyst.

And so last year we saw the horse take fright many times.

Culminating in the horse bolting in December!

And so in January, entered the horse whisperer, Jerome Powell. Even looks a little like Robert Redford no? And as we know, the market has been calmed. But like the movie, is the horse so damaged now that it will never really be calm again. Now permanently scarred, and ready to take flight at the most trivial trigger?

Perhaps. But also like the movie, the market has now been moved to a calming oasis, well away from the catalyst for its angst, namely the Fed itself. Because with the Fed not only pausing with hikes, but also discussing targeting average inflation, the Fed has well and truly put away the whip.

The markets next startle will not come from the Fed.

Which is not to say the market still won’t be startled in the near term. Because for markets, the underlying problem is still there. How do you withdraw 18 trillion dollars of support for bond markets, and raise interest rates, without spooking the horses? Even worse, are the horses so vulnerable – is so much money now invested in bonds with returns so minimal that investors are ready to bolt – that it will only take something ever so trivial to start the stampede?

Whilst one can never be sure about the emotion – the fear and greed – that so often drives investing, our view is that the Fed has demolished the immediate catalyst for the panic that was developing in Q4, and the market is likely to stay calm for now. Like 2016.

And then?

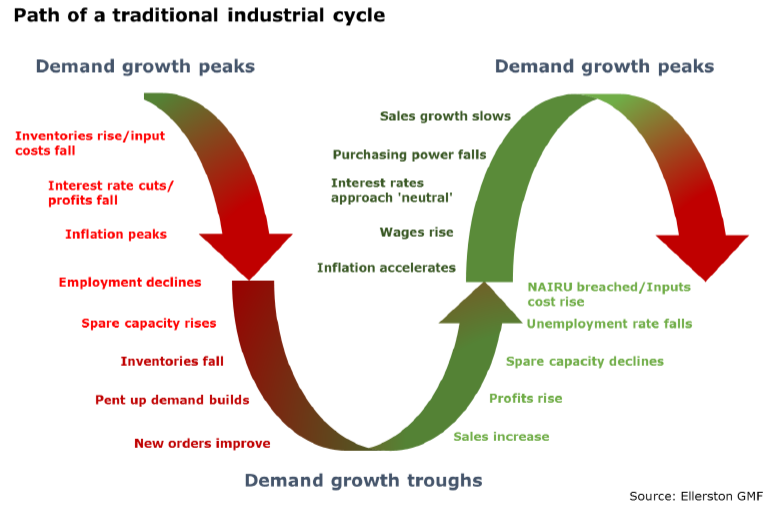

Well, eventually, the forces of supply and demand will emerge. The so called business cycle.

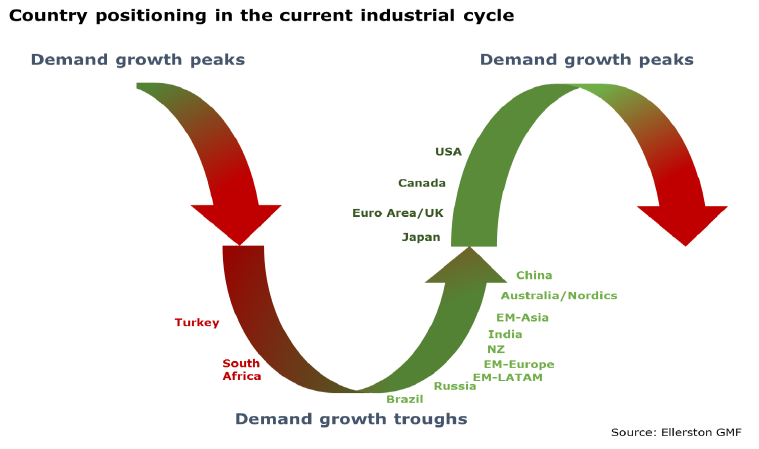

And where is the world in the business cycle? This is how we see it;

Note where the US is. Leading the world, and the part of the business cycle where wages rise, inflation rises, interest rates approach neutral and purchasing power falls.

And traditionally, certainly since Volcker in 1980, central bank orthodoxy was that if they can tap the brakes (via rate hikes) just enough to slow the economy and avoid inflation pressure, they can extend the business cycle. In the US, the 1980, 1983, and 1990 recession were caused by the Fed being just a bit too aggressive on the brakes. But then overcorrecting, the 2001 and 2008 great recession was caused by a timid Fed, avoiding the brakes, and feeding asset bubbles that eventually burst.

Is the Fed now in the same position? Dealing with another bubble of its own creation, this time in credit. Quite possibly.

Except they are not going to touch the brakes now. So now what happens?

Well like CSX Locomotive #8888, the “Crazy Eights” runaway train inspiration in the movie “Unstoppable”, we now have to look forward to the disaster point, the corner it won’t make, the elevated curve in Bellaire, Ohio.

So where is that curve? What does that curve even look like? Well, for us, the “curve” is inflation. And where is it? Well, that is a little harder to answer. But let me give you the signposts.

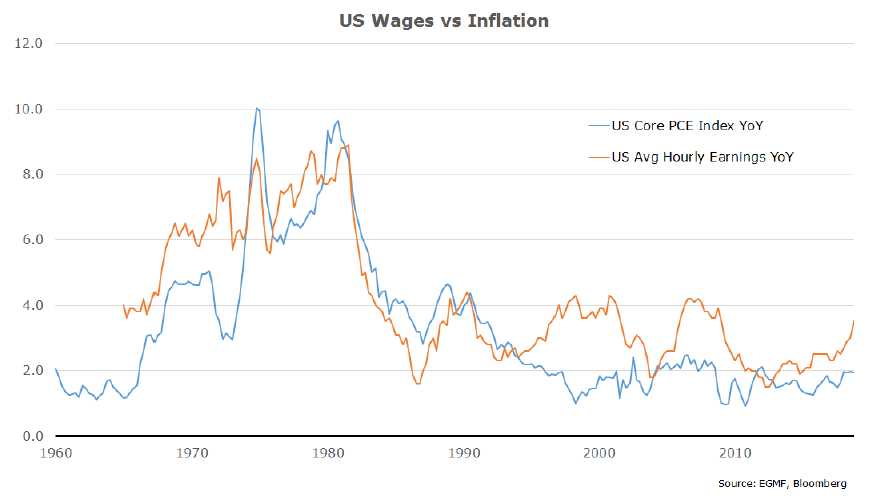

The first signpost; wages. Typically, when wages rise, inflation rises. After all, firms need to recover their costs.

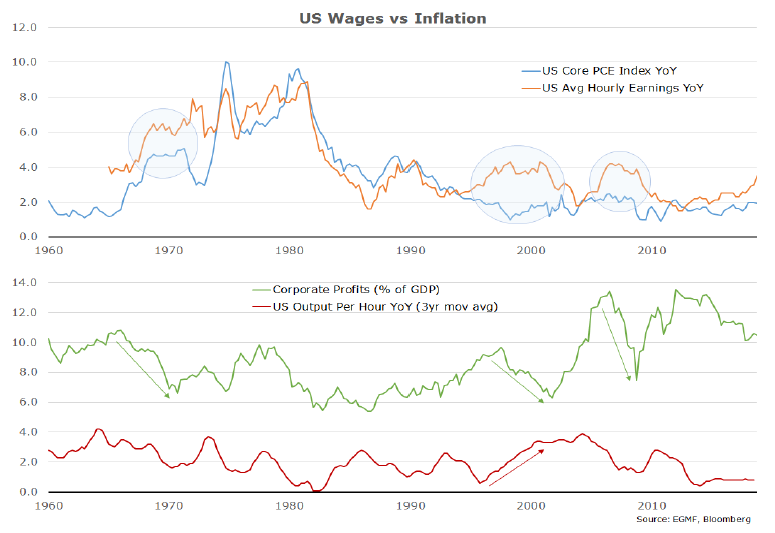

But do you see what I see? Most of the time, rising wages = rising inflation. But not in 1997-2001. And not in 2006-2008. Why? Because when wages rise, it could be because the employees have become more productive. And if they are more productive, that is not an increased cost for the firm. The cost for the firm is the labour cost per unit produced (ULC). ULC is calculated as wages – productivity. If ULC is not rising, their cost of production is not rising. This is the golden goose, a win/win for both employees and employers, the drivers of which are typically opaque and typically influenced by new inventions or labour market reform. Not something the central bank can control. But something the central bank needs to predict. Inherently difficult, but Greenspan predicted it in 1997. With the productivity enhancements of the internet. And Powell is now suggesting the same will occur. But it seems for little more reason than because productivity is too low…Well perhaps he will be right. At any rate, the red arrow below shows the lift in productivity in the late 90’s. That allowed higher wages without inflation.

The other way to have higher wages without inflation is for firms to “absorb” the cost. Note the decline in the green line in 1997-01, and again in 2006-08. That line is corporate profits as a % of GDP. Instead of passing on higher costs, firms wore it. Why? Well for one, their profit margins were relatively high at the time. One might presume that in a competitive environment, firms typically prefer to maintain market share if they can. At a profit/GDP ratio of 10.5% today, it would appear that firms today can absorb higher prices for a period still. Won’t be great for earnings of course…

Nonetheless, the tricky part for forecasting a rise in inflation is in the chart above.

- Do you think productivity will rise?

- Do you think corporate profits will fall, and more importantly, by how much and over what period?

We don’t pretend to know the answer to both of those questions – today. But we will be monitoring the trends closely so as to determine the answer well before the market. All I can honestly say today is that it could be 6 months, or two years, before rising wages translate into inflation, as far as the squeeze on corporate profits goes. Oh, and if there is a “productivity miracle”, there may never be a problem. And pigs can fly…

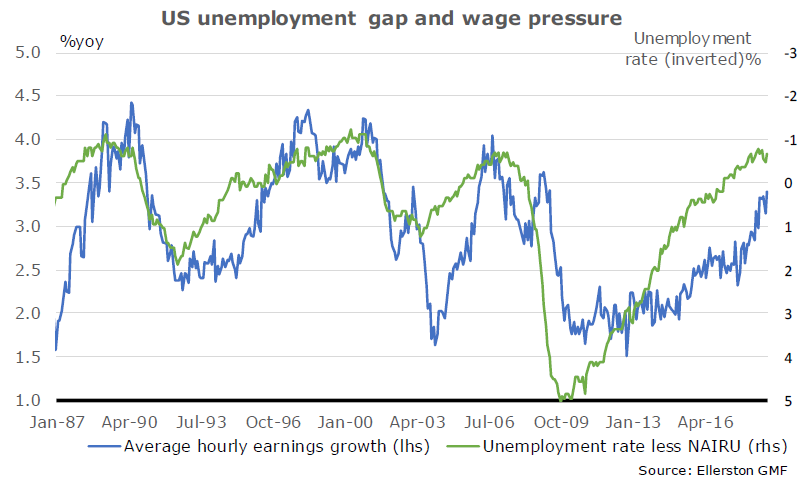

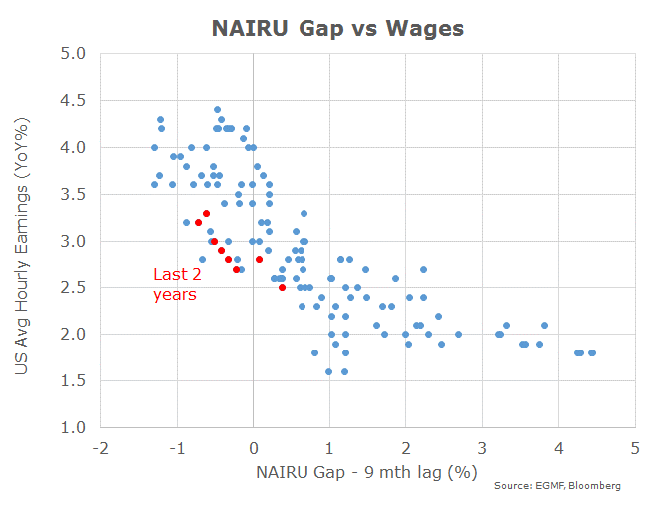

Maybe wages won’t keep rising? All questions are good questions. But this one is relatively easy to answer. As we have written before, the relationship between the unemployment rate and wages is well and truly intact. The update with the latest employment report in February only confirmed such. As the labour market tightens, represented by the green line below, which shows the unemployment rate v NAIRU (inverted), wages rise (the blue line).

Over the last 35 years, the relationship is very consistent. Wages sit around 2-2.5% when the NAIRU gap is positive (the unemployment rate is higher than NAIRU). And it really doesn’t matter how much higher. But when the NAIRU gap goes negative, 9 months later wages start to rise.

There are much more worthy debates to engage in.

Ok. So let’s take rising wages as a given. Let’s remain sceptical on a convenient productivity pickup. But open to the idea and monitoring for it. And let’s assume corporate profits decline to absorb some of the wage pressures, but we don’t know how much.

Have we been here before? Powell says yes, and points to 1997. Convenient. I say if corporates eat into their profits, it might be more like 2006. But with one new problem. Indeed, as I wrote last month, one massive change. In 2006, the Fed was still “pre-emptive”. When wages rose, it raised interest rates to slow the economy and try and quell inflation. In 2019, pre-emptive is dead; long live reflation!

NY Fed Governor Williams is leading the charge for a new policy framework, price level targeting, or “inflation averaging”. Powell is trying to calm the horses, saying any changes will be “evolutionary”, not “revolutionary”. You might say that doesn’t seem like a big deal? Isn’t that what the RBA does, target inflation to average 2.5% over the medium term? Indeed it is. But the difference is in the interpretation of how you achieve that goal. If you are targeting say 2% on average, do you always target 2%? Or if inflation has run at say 1.5% for 4 years, do you target inflation at 2.5% for 4 years? Well I can tell you the answer from one former RBA policy setter. They would never be so presumptive to think they could target say 0.5% higher for 4 years and then nicely bring it back to target. There best way to target say 2% , is to always target 2% and expect the misses to average out over time.

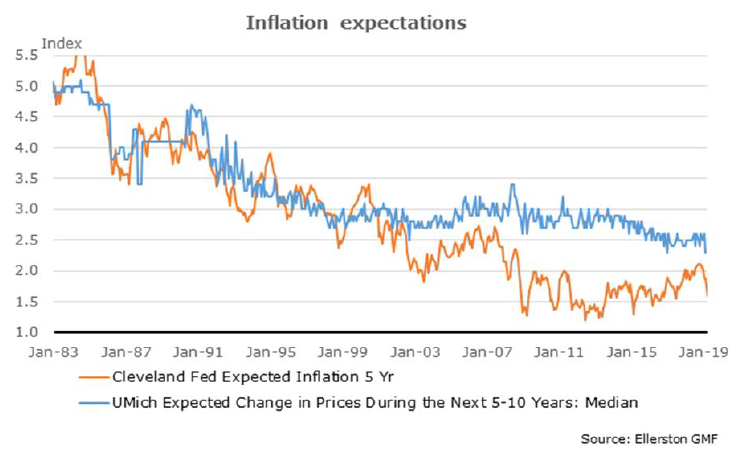

Williams takes a different view. His view is the best way to target 2%, is to stabilise inflation expectations at 2%. He believes the biggest danger for inflation is to consistently miss in one direction, as they have in the last 5 years, and for this systematic miss to “unanchor” inflation expectations, which in turn leads to lower inflation and so on. Below are two of the three inflation expectation measures he is focussed on.

So in his mind, it is imperative to re-anchor inflation expectations. And the only way to do that is to run inflation higher than target for a period, until those expectations rise. I imagine he would like to see them at least where they were prior to 2007.

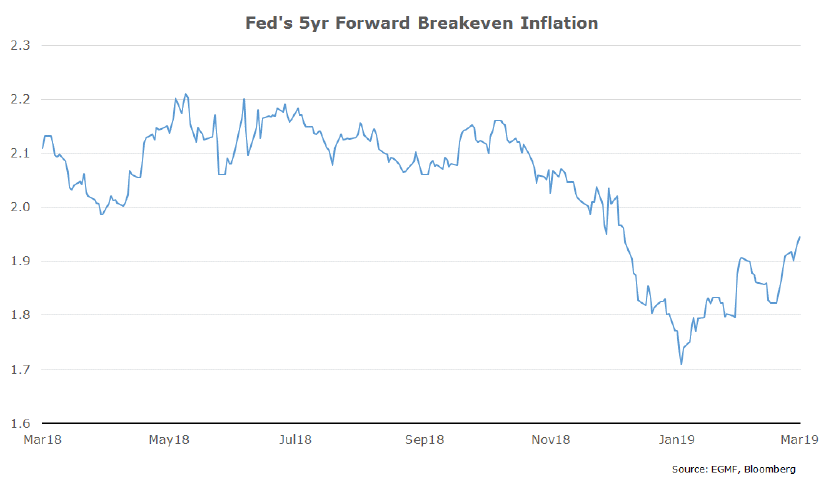

And what was the third inflation expectation measure he was focussed on? The so called inflation breakeven rate from the bond market. It dropped from 2.1% in October to 1.72% in December, and this worried the Fed. They feel they need to see this at 2.1% and going higher, not lower.

So we are backing the Fed. We think they will achieve this goal, because they are determined to. Wages are rising, and they are not going to stop it. They want it to feed into inflation. This is a world we haven’t been in since the 50’s and 60’s. Notice on the wage/inflation chart above, it was the late 60’s when the Fed lost control of inflation. The last time the Fed wasn’t pre-emptive.

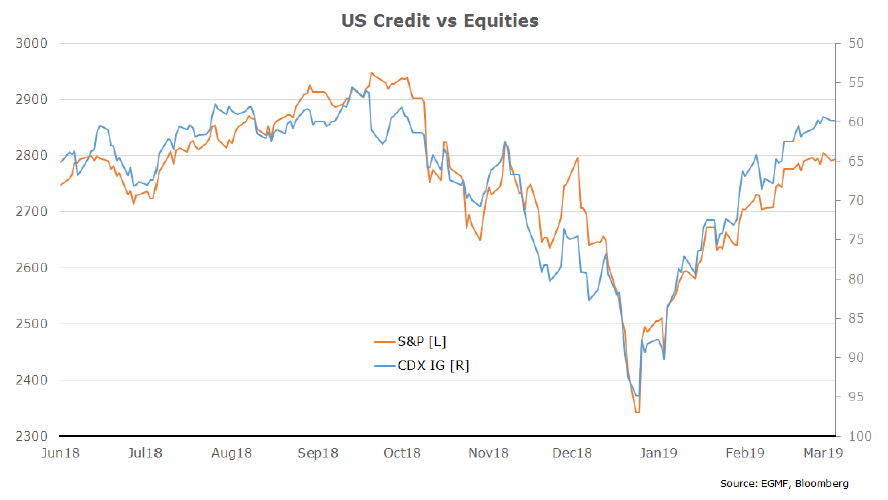

Now we aren’t saying this is going to happen instantly. As I noted above, this could take a couple of years to play out now. But it is a different playbook to last year. Last year we had a more traditional Fed, determined to normalise policy, albeit still late. The risk, which transpired at the end of the year, was that the credit bubble at some point would burst.

Now we have a Fed with a new plan. They would well and truly rather deal with inflation than a bubble bursting. We back the Fed, at least in portfolio positioning. The trade now is for reflation. We are long inflation breakeven swaps in the US. And we also like the US 5-30 curve to steepen. We still think the Fed will hike this year, but only very reluctantly, when it is very clear the economy is doing well, and financial conditions have taken another leg easier (driven by equity markets grinding out a rally). And the credit bubble waiting to burst? It will likely wait. The two catalysts to startle the horses were

- Fed hikes, and

- A recession.

The Fed’s new course of action clearly negates a), and also delays b). Something else might happen to raise concerns of a recession – a trade war perhaps? But without a rise in recession risk from an exogenous shock, we don’t see a near term endogenous catalyst. Nonetheless, the credit, or carry bubble, still lingers. Like a nervy horse, it just needs another loud noise to set it off.

Which brings me to Australia. Hasn’t the starter’s gun for rate cut calls been fired there! On the 1st of Feb, no Australian banks were calling rate cuts in Australia this year. Now we have had UBS, Westpac, NAB, JP Morgan, Nomura and Macquarie all forecasting 50 points of rate cuts this year. And I am probably missing some. We started to position for rate cuts in mid-January, and this has helped performance in February and March (so far). The market now prices one cut by August, and a 50% chance of another cut by February 2020.

So will they be delivered? I’m afraid so. I say afraid, because a key part of our forecast that sees the cuts delivered is a deteriorating Australian economy.

The RBA has explicitly linked a rate cut to the state of employment market. Phillip Lowe said last month:

…a lot depends upon the labour market. The recent data on this front have been encouraging. Employment growth has been strong, the vacancy rate is very high and firms' hiring intentions remain positive.

Mmm, it seems the lead indicators suggest his optimism is misplaced.

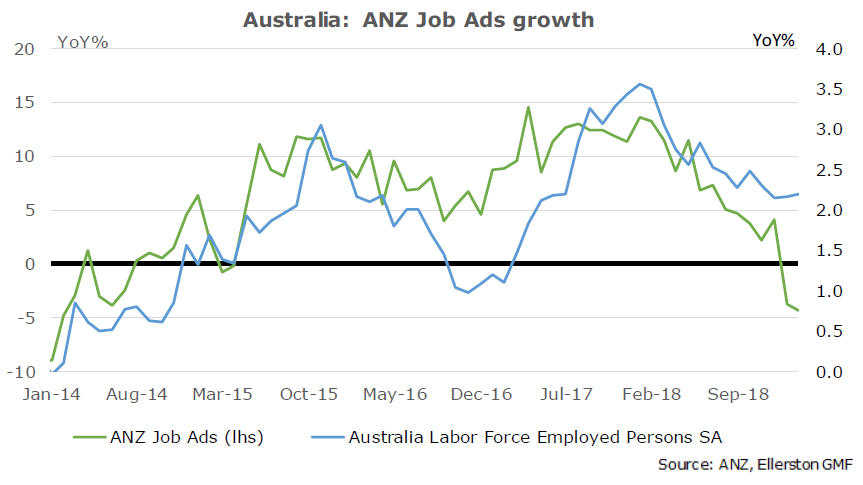

ANZ job ads have started to fall (year over year), and you would have to say the relationship to employment is pretty tight…

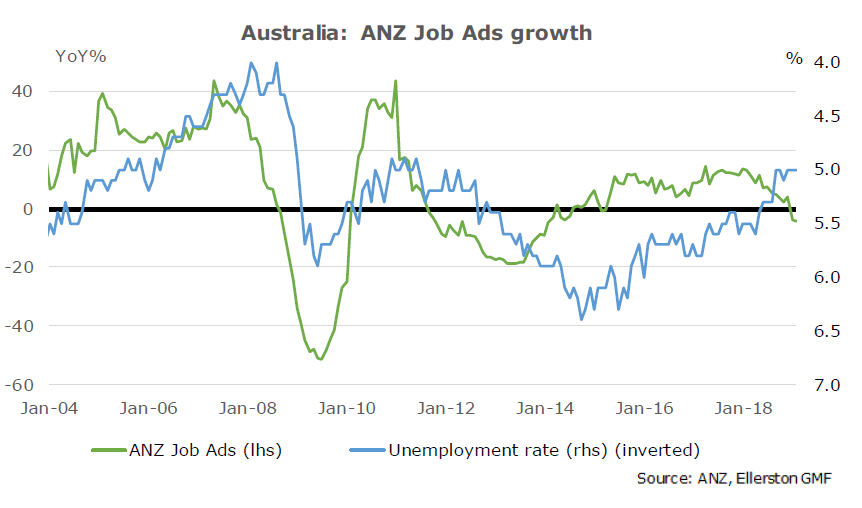

A little looser v the unemployment rate, but the implication is clear. Unemployment should soon start to rise.

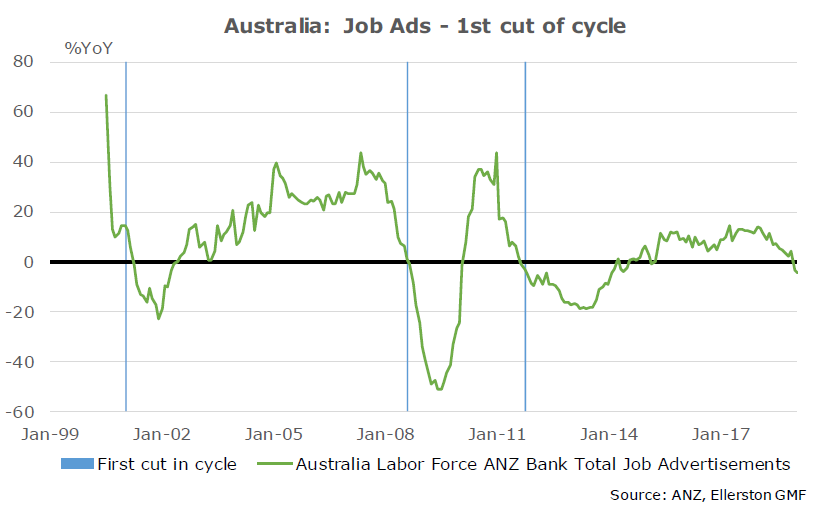

Indeed, based on this indicator alone, this is when the RBA has typically done their first rate cut.

Yet this is the only indicator holding them back from a rate cut! GDP is weak, consumption is very weak. And as we all know housing is very weak, arguably the weakest since the early 80’s. They are clearly very reluctant to cut. But the employment shoe is about to drop.

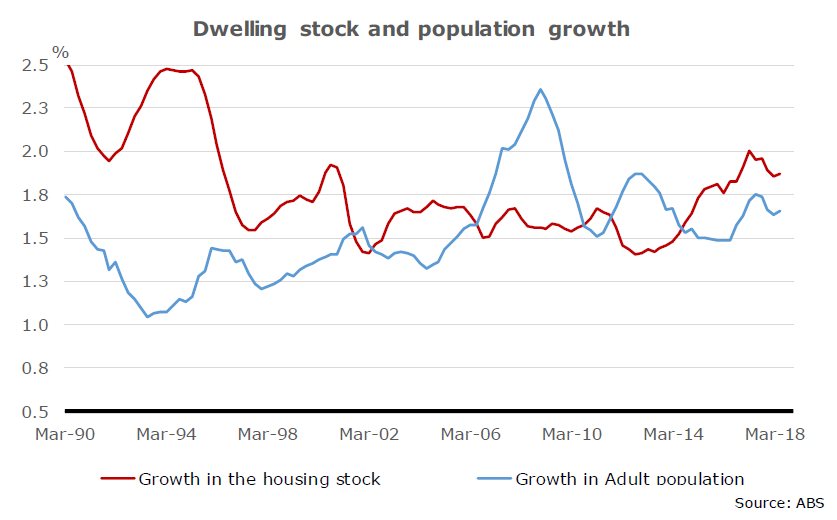

In the same speech, Governor Lowe takes comfort at the current 9% decline being “not unprecedented”. Well yes, it isn’t unprecedented in terms of magnitude. But it is unprecedented in terms of what is driving the fall. This is the only time that house price falls have not been due to higher interest rates. Rather, it is due to collision of special factors. A surge in population growth driving a much delayed and ill-timed surge in dwelling stock.

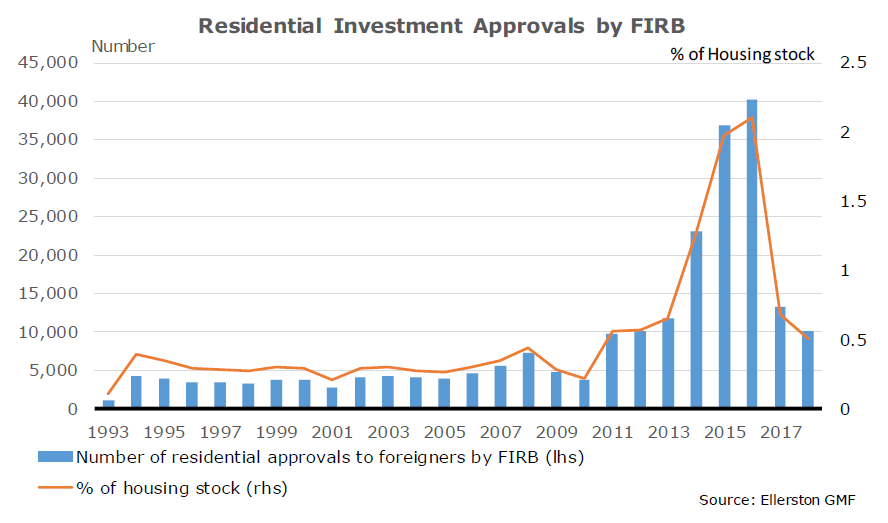

And the appearance and disappearance of the Chinese buyer. Approvals to purchase domestic property by offshore investors averaged 0.2% of the housing stock from the early 1990s until 2011 before surging by a factor of 10 through 2015 and 2016, and then plummeting back to 0.5% in 2018.

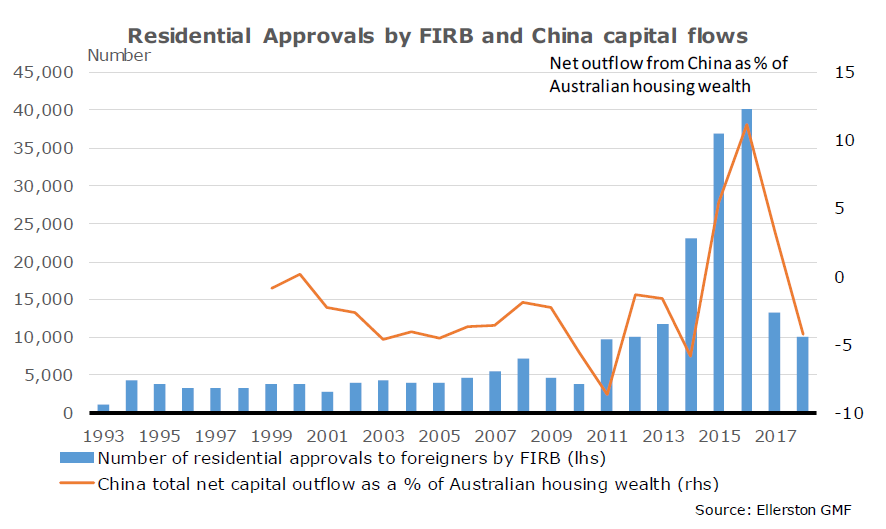

Not all of this investment came from China and the data is not granular enough nor reliable enough to be precise. Yet the surge and then retreat in foreign investment in Australian property does correlate closely with the surge and then retreat in private sector capital outflow from China over same period. Australia wasn’t the only destination of its capital, but it did unquestionably have an impact on the housing market and the perception of the sustainability of house price gains.

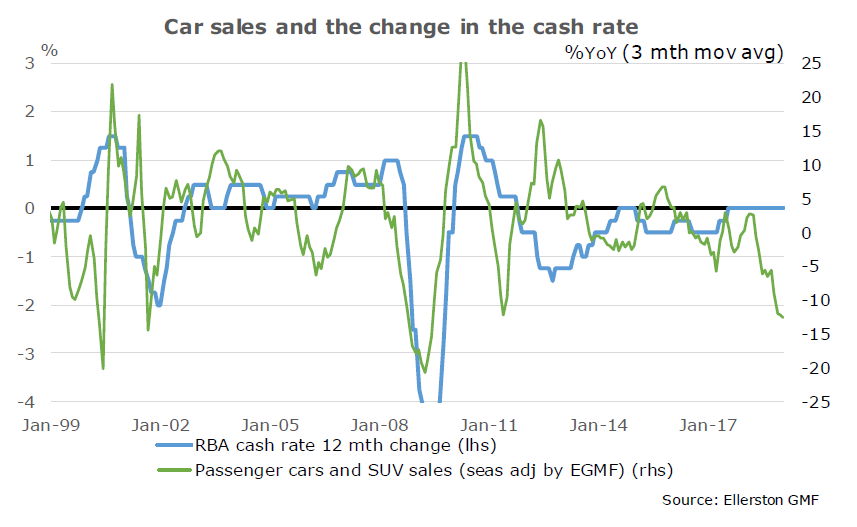

The “problem” is the impact of falling house prices on the consumer. The RBA finds the wealth effect from housing is relatively contained, impacting predominantly cars, and to a lesser extend home furnishings, clothing and utilities.

Well they are right about autos. YoY sales are approaching recessionary levels. Levels incidentally that normally illicit a sizeable response from the RBA.

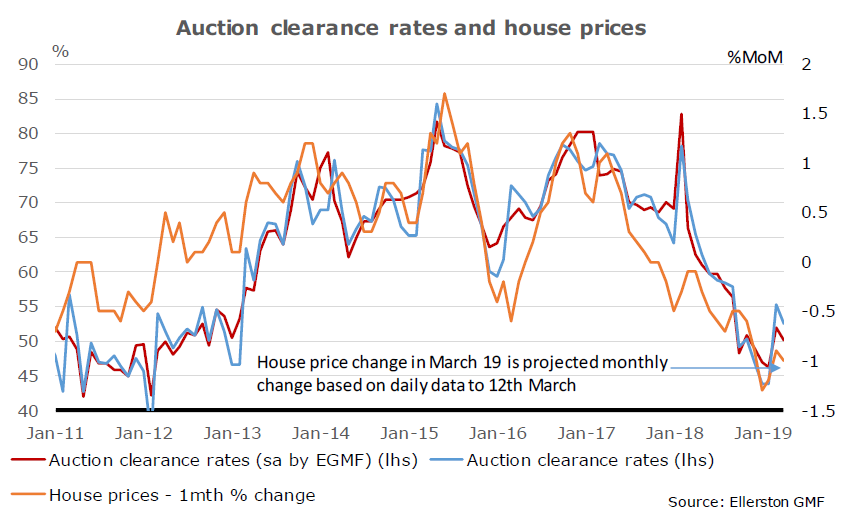

The problem my friend is there is no sign of a bottom in the housing market price decline.

Yes, 0.9% decline in Feb is better than the prior 3 months. But I would be reluctant to call it a bottom without a reason, like a rate cut. Particularly with an election looming.

Indeed, with the “perception” building that house prices continue to fall, one has to wonder if that becomes self-fulfilling? The RBA did. They just released “A Model of the Australian Housing Market”. Their model suggests that if homebuyers change their perception and believe that prices will decline by 2.5% a year in real terms (about 4-5% in nominal terms, or half the current pace…), then house prices can be expected to fall 35% over the next 5 years. Of course they don’t expect this. They conclude this “is relevant as a worst-case scenario to be guarded against”.

And so I said last month, it is time to pursue the policy of least regret. Or perhaps they prefer to say “guard against the worst-case scenario”.

What is hard to say is how much more evidence the RBA needs to pull the trigger. We are betting it is sooner rather than later, but most likely after the election, and are positioned accordingly.

Indeed, our positions are little changed from last month, which were

- Positioned for rate cuts in Australia

- Positioned for higher yields in the US (a rate hike this year, and long inflation breakevens)

- And positioned for a positive outcome on Brexit.

The last we still expect will come, but perhaps a little longer than we would like. With May’s Brexit plan expected to fail yet again, focus will now turn to an extension of the timetable. Probably till June. And then nutting out an alternative solution, most likely a softer Brexit (a Customs Union 2.0 or Norway+ plan), or a 2nd referendum on Brexit. Much less likely, though possible, would be an election. We are positioned for positive resolution over coming months (either Customs Union 2.0, May’s plan or a referendum), though admittedly sooner is better for our structures.

Never miss an update

Stay up to date with the latest macro news from Ellerston Capital by hitting the 'follow' button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

Want to learn more about big picture investing? Hit the 'contact' button to get in touch with us or visit our website for further infomation.

1 topic

1 contributor mentioned

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.

Expertise

Brett has worked in the financial services industry for over 28 years. Most recently he was Head of Global Macro at Ellerston Capital. Prior to that he spent over 10 years as Senior Portfolio Manager at Tudor Investment Corporation.