The looming large excess of housing: What to do about it, and when

In an apparent suspension of collective logic, it appears few people have asked what happens when you provide massive incentives to bring forward an unprecedented spike in house construction while simultaneously choking off future demand by halting net migration.

Away from the fog of COVID, any reasonable-minded person would have concluded that unless the starting position was a massive undersupply of housing, then this combination of policy settings would soon generate a large excess of housing.

In this wire, we summarise how large this excess in housing is likely to be, and explore the investment conclusions.

What happens when a Government program is too successful at inducing supply?

The Homebuilder program, in concert with generous incentives from state governments and mortgage rate reductions, has proven successful in bringing forward construction.

But have they been too successful?

Recall that upon the introduction of the Homebuilder scheme, the Treasury estimated that COVID-19 would see cancellations of housing projects of ~30%, compared with ~17% during the Global Financial Crisis.

This reduced the Treasury’s pre-COVID housing starts estimate of 171k to just 111k. The HomeBuilder scheme was explicitly designed to offset half of the expected decline in starts, with the aim of backfilling 30k starts in 2020-21.

That is, the Treasury was hoping to achieve ~140k housing starts once HomeBuilder was fully implemented.

Instead, approvals for houses have exploded to the upside.

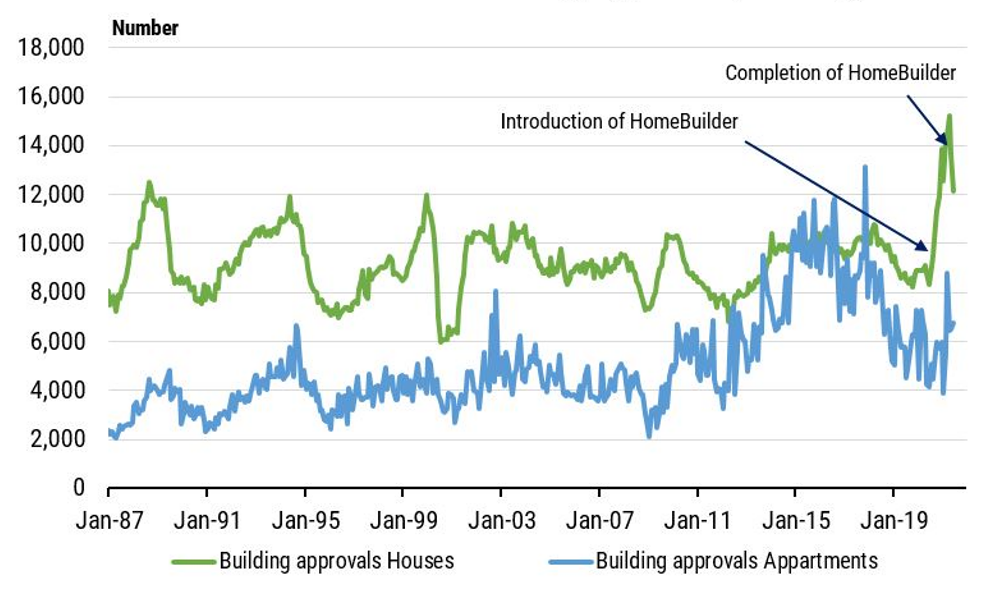

By the March quarter of 2021, dwelling approvals were annualising at 278,000 (refer to Chart 1), and even though approvals have declined from that peak, by the end of the 2020-21 financial year some 200,400 dwellings were approved.

Single home approvals were even more spectacular, with a record 136,600 approved during the year, to be 31% above the prior financial year. Of course, this also excludes the surge in approvals for renovations over the same period.

Chart 1: Australian building approvals (monthly)

Source: YarraCM

In the end, 99,300 Homebuilder applications were received by the Government to build a new home and a further 22,100 applications were received for a ‘substantial renovation’.

This means the HomeBuilder program exceeded Treasury’s objectives for new dwelling construction by 330%.

The clear lesson being never stand between an Australian household and an uncapped government program! Taxpayers have effectively handed out almost $3bn in ‘free money’ for people to build or renovate their home.

But wait - there's also the states to think about

Such Federal Government largesse was obviously well received.

However, what is less well understood is that state governments were also busily providing their own incentives, especially via stamp duty exemptions for first home buyers.

These incentives vary by state and in many instances were in place prior to JobKeeper.

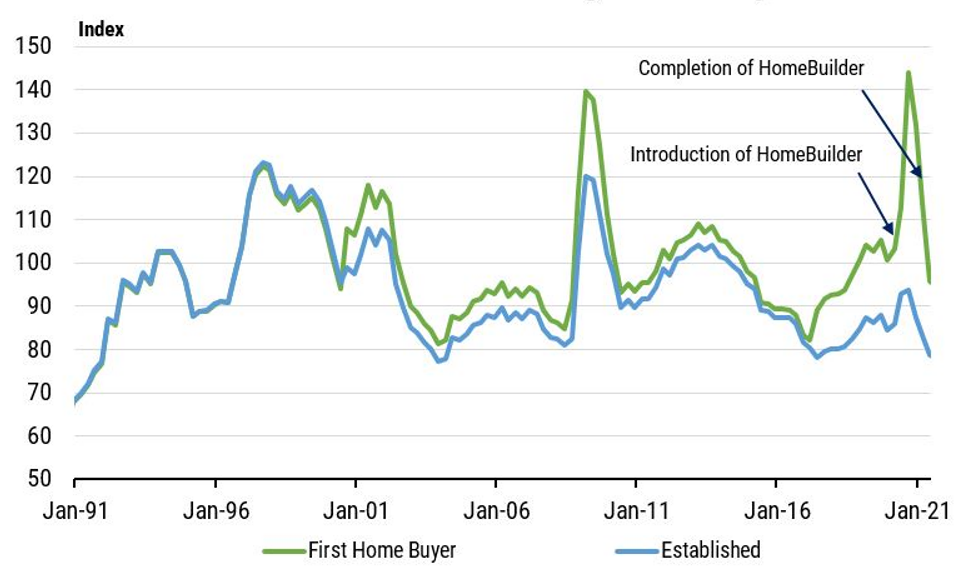

To put the incentives in context, we have created separate housing affordability indices for established and first-home buyers.

This captures all the incentives and taxes by state and federally, in addition to all the standard factors that influence affordability – house prices, mortgage rates, loan-to-deposit ratio and household income.

Chart 2: Australian housing affordability

Source: YarraCM

Chart 2 shows the enormous boost to housing affordability for first-home buyers that was provided principally by shifting government incentives.

The subsequent decline in affordability is mostly due to the lapsing of the Homebuilder incentive, although 15%yoy growth in house prices by mid-2021 has also weighed heavily on affordability.

These seismic shifts in housing affordability ultimately determines the near-term path of housing approvals.

But it is important to recognise that the incentives and inducements do not create new demand for housing. Rather they merely bring forward housing construction that would otherwise have been demanded at a later stage.

The bigger the pull forward, the bigger the decline once affordability declines back to its pre-incentive levels.

What happens when a pandemic eradicates future demand?

But what if you not only provide massive incentives to pull forward the supply of new houses but also simultaneously eradicate one-third of future demand for housing?

Housing can only be demanded by those who have placed themselves in a situation to form a household.

We spend a lot of time modelling the demographic structure of the population in Australia and how that relates to future housing demand. It’s a relatively complex process that incorporates factors as diverse as;

- Relationship type

- Number of dependants of each household

- Type of structural dwelling

- Vacancy rate of established dwellings

- Demolitions

- trends towards second or lifestyle homes

The census data is an important input for the historical analysis, however, the forward projections rely heavily upon the accuracy of the ABS’s population projections.

Although the ABS provides three main scenarios for future population growth, their projections have been rendered useless by the de facto ban on net migration from travel restrictions.

As such, we have recast the population projections by looking at the age characteristics of migrants and assumed that net migration doesn’t return to pre-COVID type levels until 2023.

By modelling the future supply of new housing as a function of the change in affordability and comparing that demographic demand for housing adjusted for the unprecedented reduction in net migration, we can solve for the likely future oversupply of Australian houses.

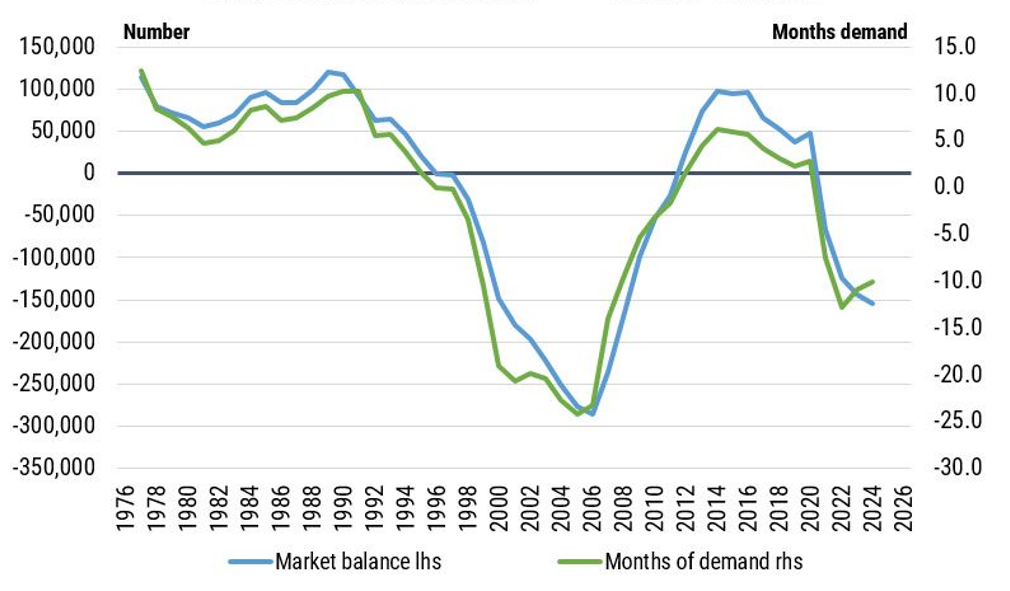

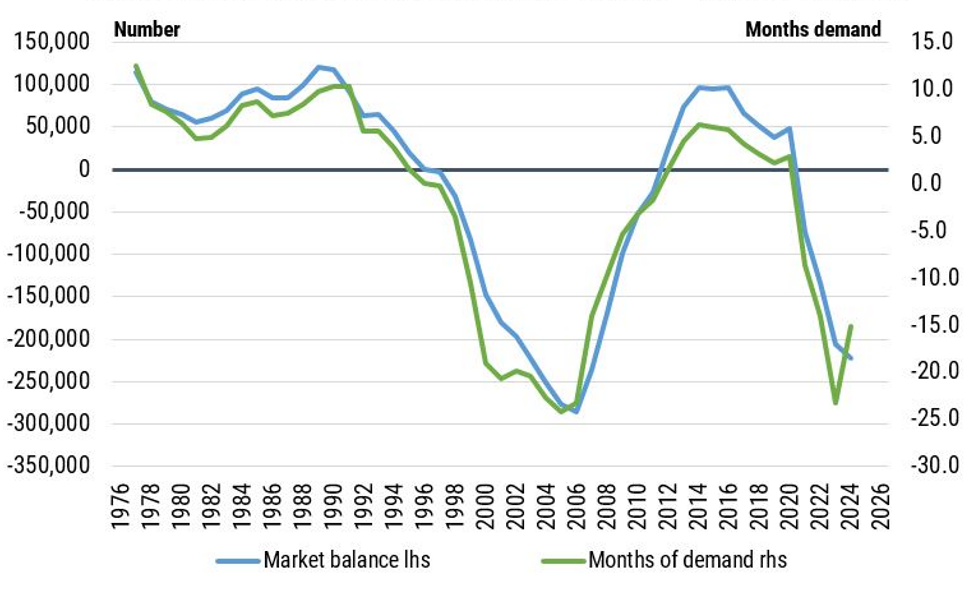

We define ‘market balance’ for housing as the most recent year that demographic demand and completions were equal in number. As such the accumulation of the difference between demographic demand for housing and completions of housing from the year of market balance determines the excess or undersupply of housing through time.

We estimate that by the end of 2023 Australia will have 150,000 dwellings in excess of demographic demand (refer to Chart 3). This would be the largest excess of housing since 2008, and this rather sombre forecast embeds as a base case of a 30% decline in dwelling approvals by the end of 2022.

Chart 3: Australian Housing - Market Balance

Source: YarraCM

What happens to the excess of established homes if the immigration recovery is delayed or if building approvals remain elevated?

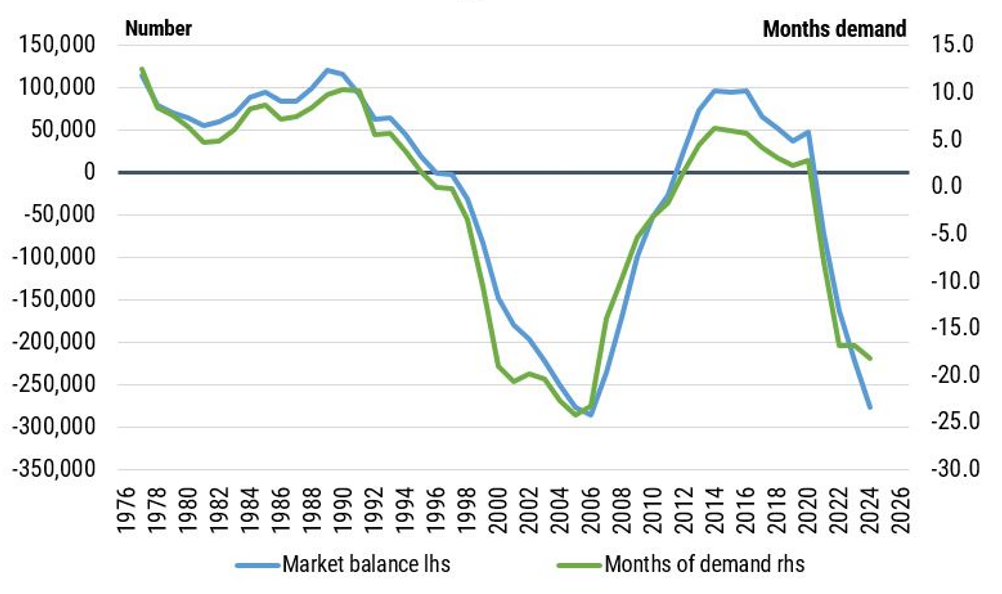

What if housing approvals don’t fall as sharply as our base case? Demand for housing is ultimately determined by demographic demand, but participants in the housing market typically operate with a more limited information set. And what happens if Australians become so enamoured with recent house price gains that Australia continues to build at an excess rate?

If we assume only a 10% decline in approvals is recorded by the end of 2022, then the excess of housing will equal the peak excess of 2006 (refer to Chart 4) which on our calculations was the greatest excess of housing since our calculations commenced in 1976.

Chart 4: Resilient approvals - Market Balance

Source: YarraCM

Alternatively, what happens if net migration doesn’t bounce back to 200,000 by 2023? How would that affect the base case? If we assume net migration of +20,000 in 2021 and +75,000 in 2022 (instead of +200,000 under our base case) the oversupply of housing will increase from 150,000 to some 200,000 by the end of 2023 (refer to Chart 5).

Chart 5: Delayed recovery in net migration - Market Balance

Source: YarraCM

What are the investment conclusions?

Just under 70% of all households either own their own home outright or are in the process of paying off a mortgage. Housing remains the largest financial asset that most households own and we estimate that by mid-2021 the value of the housing stock is $8.9 trillion – 3.7 times the market capitalisation of the ASX200 and 4.5 times the size of the Australian economy. Clearly, such a large and valuable asset should be managed with care.

Moving into a large oversupply of housing does not necessarily mean that house prices are at risk of significant decline.

The prime example is that the peak excess of housing in 2006 did not unleash a sharp fall in prices. Price growth did slow significantly during the 2003-06 period, but two important things happened that avoided the housing excess translate into falling prices.

Firstly, the combination of stronger household formation rates of the local population and a mining-related boom in immigration transformed the demographic demand for housing.

In the 10 years to 1996, we estimate the demand for housing averaged 140,000 per year. In the 10 years to 2006, housing demand had slipped to just 118,000 per year. However, in the period since 2007, Australia’s annual housing demand has averaged 199,000, with a large step-change occurring in 2006 due to more Australians moving into key household formation age brackets and the surge in net migration associated with the mining boom.

This step-change was crucial in gradually absorbing the excess of housing that had previously accumulated.

Secondly, the Global Financial Crisis and the subsequent slow economic recovery saw the RBA cash rate decline from 7.25% in August 2008 to 0.75% pre-COVID and just 0.10% post-COVID. Capitalising low-interest rates into house prices has become something of a national sport ever since.

The problem facing Australia today is two-fold: (i) interest rates are today at the lower bound, and (ii) housing demand is now hostage to the evolution of the pandemic and how fast we choose to ramp up immigration in the post-vaccination phase.

Quite simply, the RBA cannot cut any further and politicians may be reluctant to open up immigration from low-vaccinated countries.

In our view, repeating the good fortune of the post-2006 period seems highly unlikely.

Contrary to the current fervour of house buying, the risk of lower house prices over the next two years is at least as high as further house price increases.

As in most financial markets, confidence is always highest at the peak in prices. We are not using this analysis of excess housing to suggest a sharp decline in house prices is imminent.

Indeed, low real mortgage rates may sustain prices at elevated levels.

Rather, we are suggesting that expectations of ongoing house price gains over the next two years may be disappointed and, more importantly, the boom in new single house construction will be followed by a deep downturn.

The first investment conclusion

Banks should be thinking in terms of building provisions against the risk of weaker prices, rather than continuing to release provisions as seen over the past 12 months.

The failure to do so may risk P/E multiples de-rating once the oversupply of housing becomes clear to financial markets. Clearly, bank average LVRs and bad debts are low by historical comparison, providing ample protection against any house price declines.

Nevertheless, the boom in new borrowers for single homes on the periphery of the major cities are yet to build equity in their homes and are more vulnerable to any decline in house prices.

The second investment conclusion

There is really only one way to avoid a large oversupply of housing, and that is to stop building so many of them.

Our base case has a significantly larger decline embedded than the consensus view and is well below that of the RBA which is currently forecasting dwelling investment declining just 0.5% in 2022, before rising again.

Ultimately, it is at this point where we disagree the most.

As stated above, you can’t create new housing demand, you can merely alter the timing of when that demand is realised. No more rate cuts, lapsing of incentives and damaged affordability via recent price spikes will see dwelling approvals fall sharply, particularly single home approvals.

The only way Australia avoids a significant excess of housing by 2023 is if approvals fall far more than anyone expects.

With full knowledge that building material company earnings will remain robust as the backlog of homes and renovations to be built remains large, it is the trajectory of housing approvals that have historically governed the share prices of these companies.

It has been a great ride up for the building material companies, but we are past the peak, and the outlook today looks increasingly gloomy.

The final investment conclusion

The RBA will not be tempted to raise interest rates while the housing construction sector – the most interest-rate sensitive sector in the Australian economy - transitions from boom to bust.

The RBA will only be tempted to commence the rate-hiking cycle once inflation has been at target for at least six months, wages are approaching 3% growth, net migration is firmly on the path to recovery and the housing approvals downcycle is complete.

These criteria are highly unlikely to be achieved prior to 1H23, so regardless of what other central banks do in the interim, the RBA’s record low-interest-rate setting is set to remain for a long time yet.

Never miss an insight

Stay up to date with all my latest macroeconomic insights by hitting the follow button below and you'll be notified every time I post a wire.

1 topic