The Looming Oil Shortage

Four long and mostly painful years. That’s how we feel when reflecting on for Forager’s investments in the oil slick. There have been a couple of successes, one disaster and an inordinate amount of volatility.

The glut was supposed to be over by now. In the September 2013 Quarterly Report, we wrote that, by 2015, increasing production from US shale oil would be “easily absorbed by an estimated incremental demand of 4 million barrels from non-OECD countries over the same time frame”.

While correct on demand, that forecast was about as wide of the mark as you can get. An excess of supply persisted well into 2017.

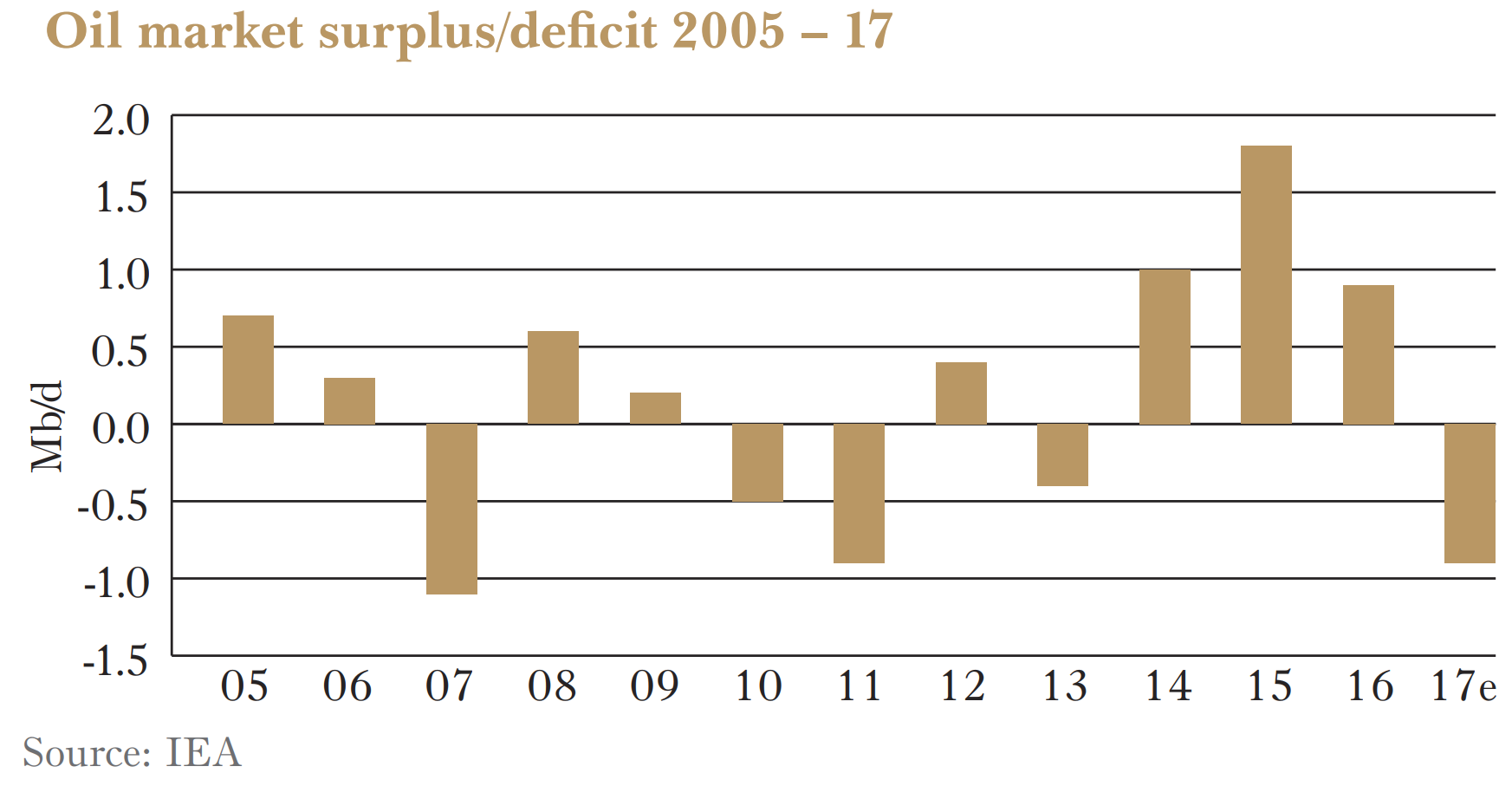

At the risk of looking even stupider, we are maintaining exposure to a higher oil price. This year the surplus has become a deficit. It’s likely that this deficit will widen over the next few years and, unless many billions of dollars are spent soon, the world is facing the prospect of a significant shortage of oil in the early years of next decade.

Demand and global growth

The dramatic and protracted downturn in the oil price has been posited by many as heralding the end of fossil fuels. That may be a conversation we are having in 10 years’ time, but it is not the cause of this current downturn.

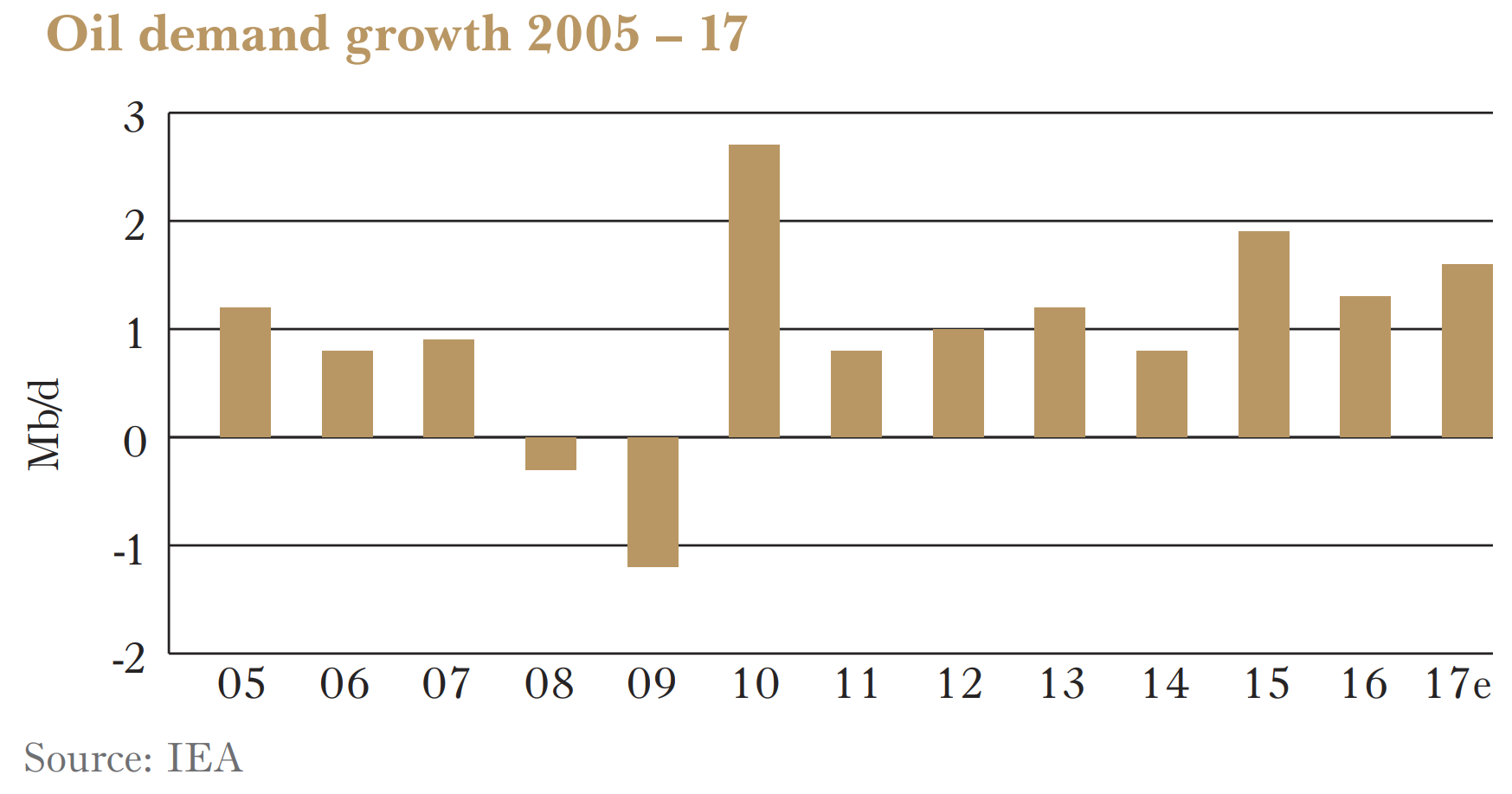

Global demand for oil has been consistently ahead of expectations, and the growth seems to be accelerating. There are two explanations. Global economic growth is more robust than it has been for a long time. And a low oil price has encouraged consumers to buy cars that guzzle a lot more fuel. In the first half of the 2017 calendar year, there were 90,302 electric vehicles sold in the US. That is approximately one fifth of the number of Ford F Series sales in the same period (429,860).

The increase in global demand in 2017 – two million barrels of oil per day – has done more than anything else to rectify the oversupply that existed in the oil market.

Combined with cuts in production from the OPEC cartel, surging demand has turned a 2 million barrel per day surplus into a one-million-barrel daily deficit. The glut is already shrinking, and it is going to start shrinking faster.

Oil is a money game

When first investing in the oil space the theory was that there is no cure for low prices like low prices. The market is oversupplied so the oil price falls. A low oil prices means investors don’t spend any money adding new supply. The market goes back into balance and the oil price goes back up.

There is nothing wrong with the theory—there is no market where the theory works better. The mistake made was underestimating the time lag between price signals and the impact on supply. It is at least three and more likely five years between an investor making a final investment decision (FID) and an oil project producing oil. Premier Oil (LSE:PMO), a UK oil producer once owned by the International Fund, is expected to bring its large Catcher project on stream later this year. The oil was discovered in 2010, the project was approved back in December 2013 and will finally add 60,000 barrels of oil a day to global production by the middle of 2018.

US shale oil has proven adept at responding to price signals within months, but for the remaining 90% of global supply, adjustments take time.

This lagged response works both ways, of course. The number of FIDs in the past three years has been lower than at any point since the 1940s. Among the oil majors, the rate at which they are replacing the reserves that they are extracting has fallen to 20%. There are still enough projects coming on stream to meet 2018 demand, but in 2019, 2020 and beyond, the lack of investment over the past few years is going to cause a serious shortage of supply.

Norwegian bank Pareto estimates an annual shortfall of 7 million barrels per day by 2020, a gap that it expects to widen from there.

Shale to the rescue?

The world clearly needs to add new supplies of oil over the coming few years. The remaining questions, then, are where that supply is going to come from and at what price it can be produced. If the US can add 7 million barrels per day of production at a price of $50 per barrel, then the world doesn’t need offshore oil and the price doesn’t need to be higher.

If that’s the case, our investment in Halliburton (NYSE:HAL) is going to be very fruitful. The oil services giant is heavily exposed to US onshore production and the amount of work and money required would need to soar. It is hard to see that scenario being plausible, however.

Firstly the economics of US shale are particularly murky. There is much talk and many presentations suggesting large swathes of US shale can be profitable at oil prices of US$40 a barrel. But investors are noticing that it is much easier to put numbers on a Powerpoint slide than it is to put cash in the bank. As industry guru Art Berman wrote in a March 2017 blog:

Most companies and analysts routinely exclude G&A (General and Administrative costs or overhead), royalty payments, federal income taxes, depreciation and amortization (“EBITDAX”) from their costs. Excluding cost is an excellent way to reduce break-even price except that it does not accurately represent break-even price.

Secondly, there simply isn’t enough of it to satisfy the world’s requirements. Oil production from US shale currently equates to less than 5 million barrels of oil per day out of total US production of slightly more than 9 million per day. It can (and will) grow in the coming years. The production shortfall mentioned above already assumes total US production increasing to 12 million barrels per day. That alone will require higher prices but it won’t be enough.

Notoriously difficult sector

Operational and financial leverage has made the long and protracted downturn particularly difficult for investors, including us. For the most part that leverage remains and there will still be restructurings and bankruptcies over the coming few years. It is not a space for large portfolio exposures.

It is a place for some exposure, though. Development money clearly needs to be spent and oil prices need to be higher to encourage that expenditure. As painful as the past four years has been, now is not the time to be bailing out.

If you are interested in receiving the here.

.jpg)

.jpg)