The price you pay matters (and a closer look at the state of valuations)

It's relatively simple for cash and bonds

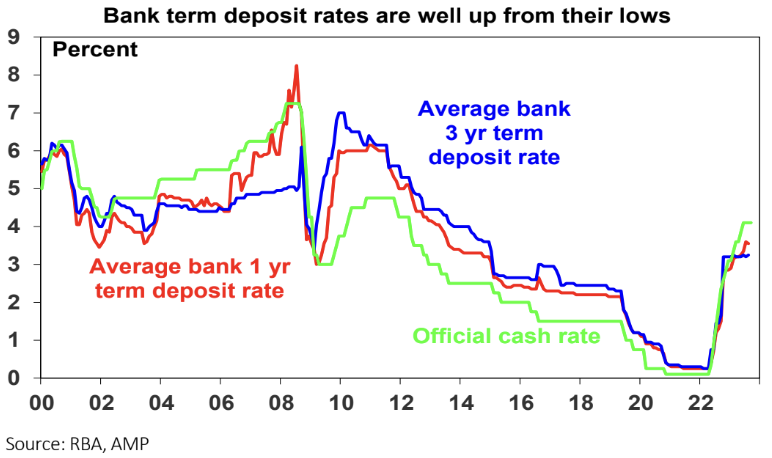

Recently term deposit rates have increased with the RBA cash rate and so are offering a more attractive return potential, albeit they are still down from levels around 6-7% in 2010.

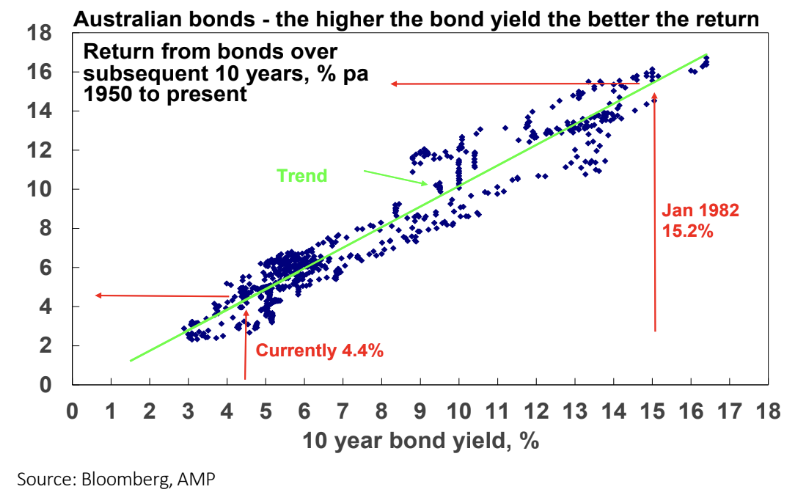

For government bonds in advanced countries, the yield is similarly a good guide to starting point value and hence medium-term return potential.

If the yield on a 10-year bond is 5%, and you hold the bond to maturity, your return will be 5%. Of course, the relationship is not perfect but it’s a good guide. This can be seen in the next chart which shows a scatter plot of Australian 10-year bond yields since 1950 (horizontal axis) against subsequent 10 year returns from Australian bonds based on the Composite All Maturities Bond index (vertical axis).

For example, Australian 10-year bond yields in January 1982 were 15.2% and it’s not surprising that bond returns over the next 10 years were 15.4%. At their low point of 0.6% in 2020, they were pointing to very low returns but they have now increased to around 4.4% pointing to better medium term returns, albeit still historically low.

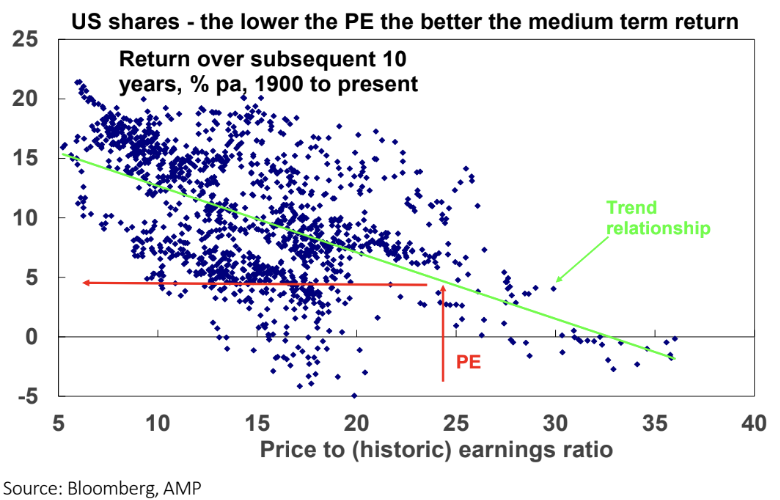

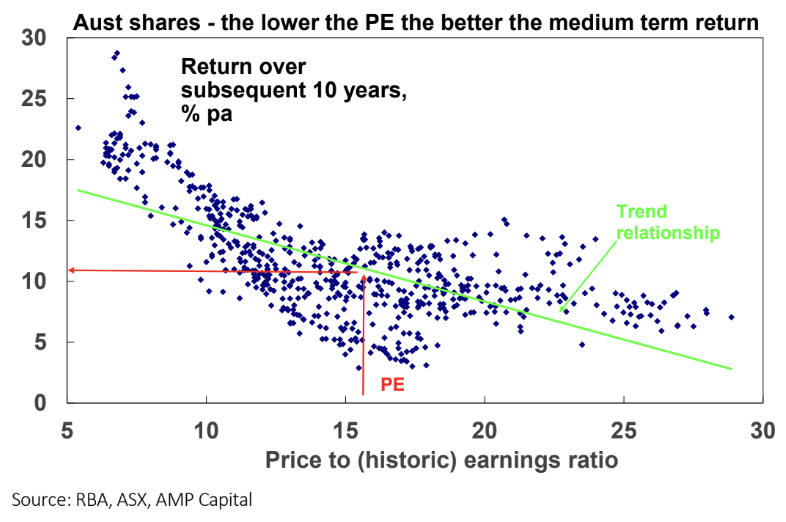

That means when share prices are high compared to earnings, subsequent returns tend to be low and vice versa. The best time for shares is after P/Es have fallen to single digits.

For example, at the end of the mid-1970s bear market in September 1974, the PE was just 5.4 times which was a great time to buy as Australian shares returned 21.8% pa over the next decade.

Note: If you'd like to see more stocks with that lower P/E ratio, you can check out the Market Index low P/E scan here.

Of course, valuation is not a perfect guide to returns

This leads many to buy only after good times, only to find they have bought when shares are overvalued and therefore find themselves locked into poor returns. And vice versa after a run of poor returns. So, when valuations matter the most, they often get ignored. But of course, valuations can have their own pitfalls.

- First, you need to allow for risk. Sometimes, assets are cheap for a reason. This can be an issue with individual shares, e.g., a tobacco company subject to lawsuits even though current earnings are fine.

- Second, valuation is a poor guide to market timing, often being out by years. To paraphrase John Maynard Keynes, the market can remain expensive (or cheap) for longer than you can remain solvent.

- Third, there is a huge array of valuation measures when it comes to shares. For example, the “earnings” in the PE can be actual historic earnings as reported for the last 12 months, consensus earnings for the year ahead or earnings that have been smoothed to remove cyclical distortions. All have pros and cons.

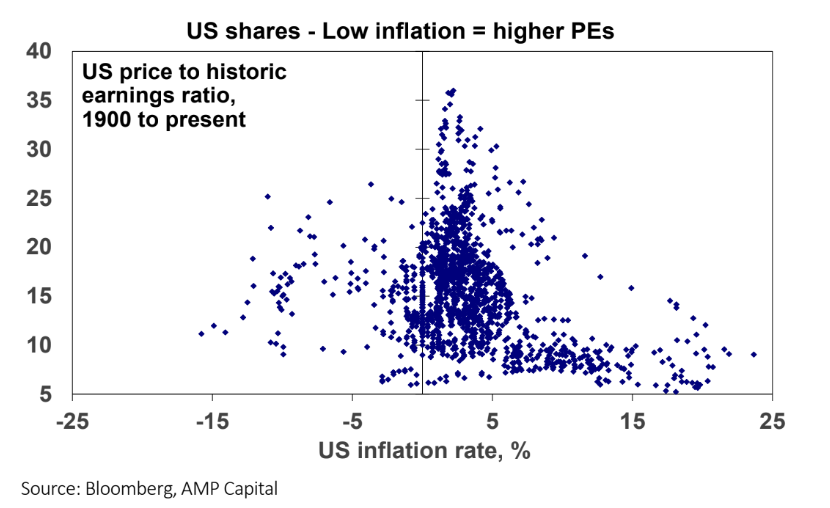

- Finally, the appropriate level of valuation will vary with inflation and interest rates. In times of low inflation, assets can trade on lower yields as the yield structure in the economy falls, uncertainty falls and (for shares) the quality of reported earnings improves. This means higher PEs.

But if inflation rises resulting in higher interest rates, then shares should trade on lower P/Es as investors find shares less attractive, uncertainty rises and earnings quality falls. This, of course, was a major factor weighing on share markets last year.

It follows from this that shares should trade on higher price to earnings ratios when interest rates fall and vice versa when they rise, all other things being equal. This is why interest rates can’t be ignored when valuing shares.

Current valuation signals

Cash – Cash and term deposit rates at 4% or so are far more attractive than was the case two years ago but are still below the rate of inflation.

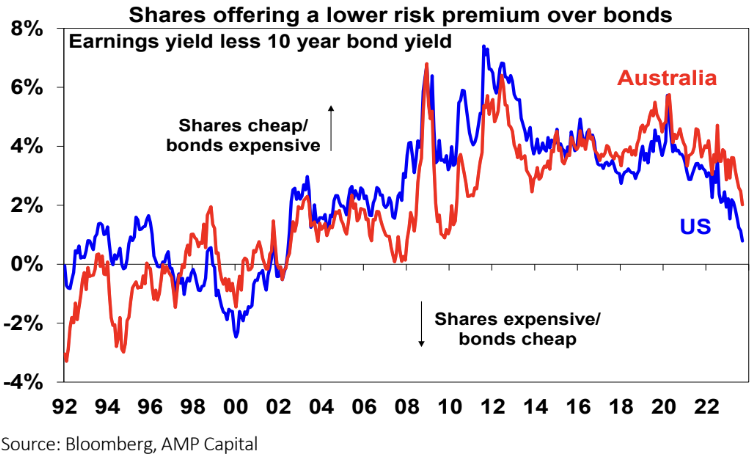

Shares – P/E ratios for shares point to a medium-term return potential of around 10% for Australian shares but just 5% for US shares (see the red lines on the PE charts earlier). Allowing for the rise in bond yields – by subtracting 10-year bond yields from the earnings yields (using forward earnings) – shows US and Australian shares now offer a reduced return premium over bonds of around 0.8% in the US and 2% in Australia.

For the US, this is the lowest risk premium over bonds since after the tech wreck whereas current uncertainties (around interest rates, recession risk & geopolitics) suggest the risk premium should ideally be higher. Fortunately, that for Australian shares is more attractive.

But ideally bond yields need to fall to improve the prospects for shares. If we are right and inflation continues to fall over the year ahead, then this should allow lower bond yields and provide some support to shares. But in the near term, the risk of a further correction in share markets led out of the US remains high reflecting the deterioration in US share valuations particularly for tech stocks which are very sensitive to bond yields.