The RBA’s tango with the Fed can’t last

The expected path of cash rates in different countries is supposed to be driven more by local concerns, unlike longer-dated bond yields which tend to move in greater unison. Indeed, the RBA’s expected cash path has marched to quite a different tune to the Fed but something changed from late last year when the two paths became incredibly tightly synchronised as if running a single monetary strategy. This outcome is puzzling and suggests a bumpier outlook for housing and credit, not to mention a lack of credibility for the RBA’s new policy framework. We think it cannot last.

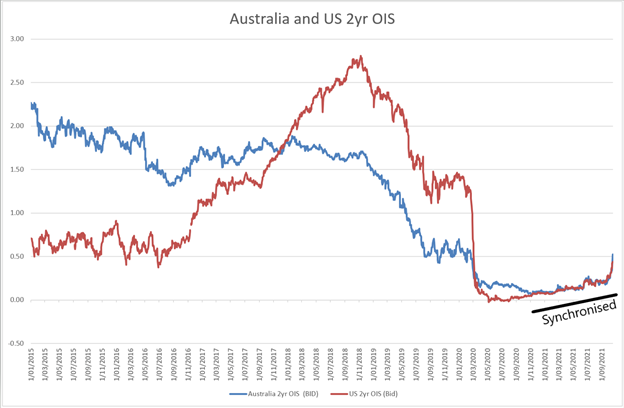

The following chart shows the historical path of the 2-year Overnight Interest Swap (OIS) rate for the RBA and Fed. This is a derivative that expresses the average expected official cash rate over the next 2 years. It is evident that they mostly march to their own tune, driven by domestic variations in the degree of slack in the economy, demand for foreign capital and inflation experience, amongst other things. Yet, from late last year, this independence has almost completely disappeared, and the two rates have been moving in unison so tightly that it may as well be a single policy body setting the cash rate in both countries. Australia appears to have become a US state for conventional monetary purposes:

Although we may have formed AUKUS, global spill-overs from the Biden stimulus packages will harmonise growth a little, vaccine coverage is converging, supply chain frictions cross borders and energy is globally priced, it is hard to make any argument on economic linkages which should generate that degree of synchronisation. Notably, the AUD has been playing its traditional role of providing some buffer against adverse global economic outcomes which should reduce the degree of economic synchronisation. Whilst it is always possible to generate scenarios and niche arguments to argue for synchronisation in monetary outcomes, powerful imaginations are required to reach this type of outcome.

The RBA’s Credibility appears to be quite weak at present

The RBA and Fed follow different policy rules, but both recently shifted emphasis towards observed inflation rather than forecasts of inflation following detailed reviews. Both kept a strong emphasis on achieving full employment with the Fed adding a few tweaks which gave more emphasis to inclusive growth and being asymmetrically concerned for shortfalls to achieving full potential. The RBA has repeatedly emphasised that actual (core) inflation would need to be sustainably within the target 2-3%pa band before raising rates, keeping a close eye on wage inflation being consistent with that.

The Fed dot plots suggest that the first-rate rise could be as soon as next year and almost certainly by the end of 2023. In contrast, RBA Governor Lowe recently re-iterated that their central case expectations do not result in the first-rate rise until 2024.

The OIS paths align adequately to the Fed’s expectations, but it is a fairly long way from the RBA’s guidance. In Lowe’s words, the market’s deviation from his guidance is ‘difficult to reconcile’ and he finds it ‘difficult to understand’. The market’s expectation for the Australian cash path, however, is quite reasonable if you simply ignored the recent modifications of the RBA’s policy rule.

Expected Inflation

The following table compares the forward-looking inflation expectations for each of the next 10 years, as inferred from the inflation swap market. The RBA and Fed are exercised about ensuring inflation expectations remain anchored around target levels (2% for the Fed and 2-3% for the RBA). For this purpose, the expectations between years 6-10 are most closely watched.

The expectations in Australia are almost exactly where the RBA would hope but the expectations in the US are now materially above their targets:

The recent inflationary experience in the US has been more extreme than Australia’s and this has probably contributed to expectations there reverting from a higher point. The US experience was also driven substantively by issues relating to supply chain difficulties which might take a while to abate (eg autos) and they will be heading into the winter where the IEA recently estimated that heating bills will rise by 20-50%, depending on the temperature with the range encapsulating +/-10% vs average winter experience. A cold winter in Europe could exacerbate the shortage of gas supplies there and it will not take much for the significant under-investment in energy infrastructure to take headlines and kick start a narrative that high energy prices will be with us for a while. The breadth of items experiencing higher inflation is also increasing as the effects spread, including for housing costs which may persist for a while.

A critical matter which can flick the switch between a transitory inflation expectation and a non-transitory one is how wages are determined. The presence of rigid wage-price bargaining played a key role in the stagflation experienced in the 1970s. Despite high energy prices which were experienced in the 1980s and 2000s, the reduced rigidities were one important element that contributed to significantly different inflation outcomes. Whilst the collective bargaining power of unions is less prevalent now than in the 1980s, the significant shortage of available labour currently evident in the US, declining consumer confidence due to inflationary concerns, even higher awareness of declining real incomes as Christmas shopping runs into supply shortfalls and the upcoming sticker shock from heating bills will bring them closer towards the conditions required to breathe life into this dynamic again.

Workers are quitting jobs at record rates, have bargaining power not seen in decades, are feeling the effects of inflation and can choose from employers who are eager to rebuild staff count and having great difficulty doing so. Anecdotally, taking a customer service role has become particularly unpleasant in the US as the behaviour of customers has deteriorated relative to pre-Covid. Perhaps informal hardship allowances will even find their way into wages of front-line service staff.

Unlike the Japanese, where Abenomics did not manage to create a virtuous cycle including wage and price inflation despite very low unemployment rates, Americans are less hesitant to ask for a raise.

In Australia, inflation outcomes have been less extreme, albeit also elevated for headline figures. The sources of inflation have been different and largely due to base effects (especially childcare) with increments in costs for healthcare, fuel and tobacco. There is clearly a different tone to inflation arising for these reasons. One emerging concern, however, is the housing component of inflation where furnishings and cost of building may rise more quickly and persist for longer. Nonetheless, given the sensitivity of the AUD to the Terms of Trade, so long as an Emerging Markets crisis does not develop, a rise in energy prices may not pass as directly into Australia’s inflation experience.

The US has inflation expectations which exceed their targets whereas Australia’s are in line with target. The risk of inflation becoming unanchored in the US is also materially higher than Australia’s at present. When it comes to inflation expectations, the cash path for the US should exceed Australia’s.

Expected Employment

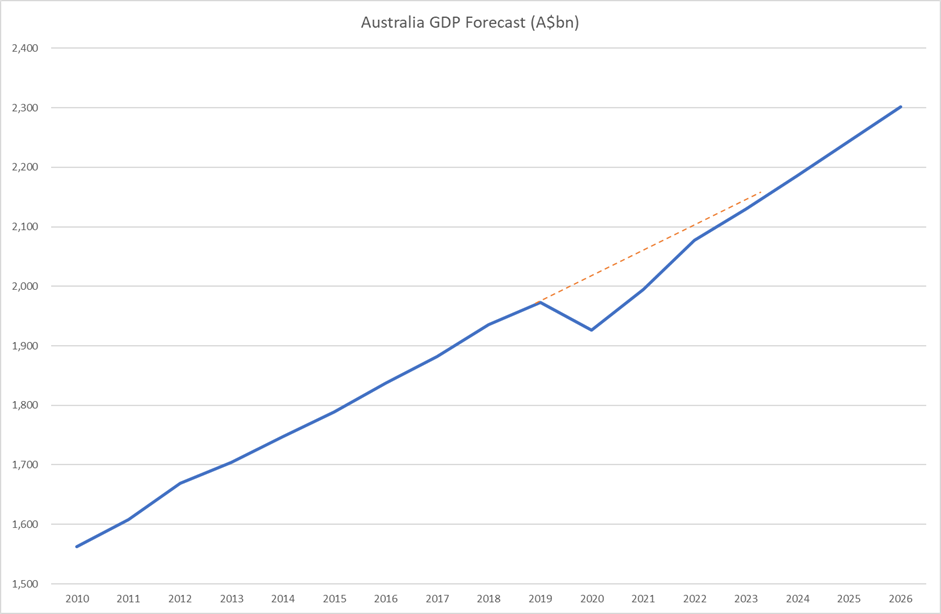

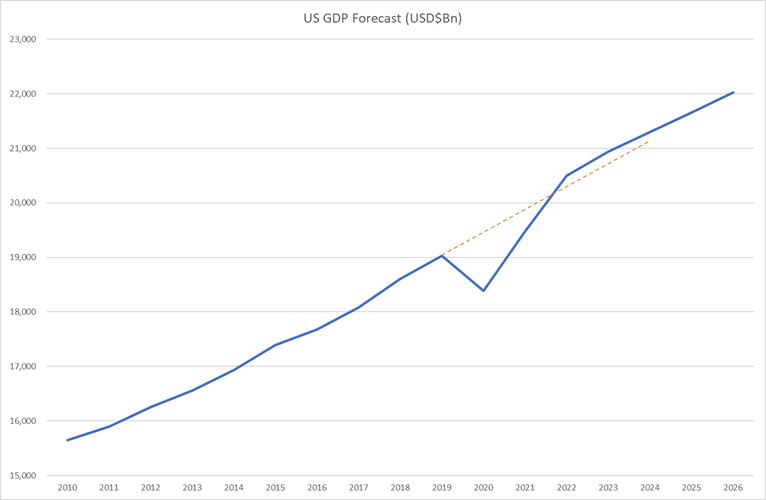

We can gauge the outlook for employment by examining the projected GDP path and working population. The following GDP forecasts are taken from the IMF’s release last week.

The Australian economy is expected to largely close the gap to the pre-covid path by the end of next year:

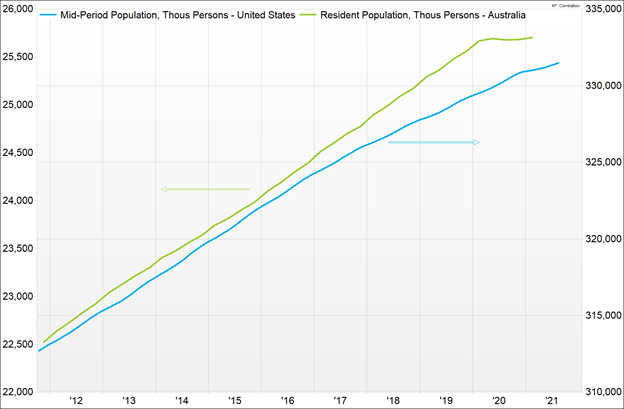

However, following a surprising outcome where the official employment figures showed that total employment rose above pre-covid levels earlier this year it was apparent that, at least in part, the departure of temporary residents, who are not counted in these statistics, created vacancies which were filled by others still in the country. Australia also ceased growing via net inwards migration. The effect of border closures on our population is clearly visible, whereas population growth was relatively unhindered for the US:

The RBA places great store on tension in the labour market as a precursor for inflation to sustainably achieve target levels. It is a key reason for their belief that the first rate rise won’t take place until 2024. When they framed those expectations in August, it was estimated that borders would not re-open until mid-2022. We have now learned that the true schedule will be more than six months earlier and this will delay the date at which the labour market will reach critical thresholds. It will also relieve wage pressure at points of critical shortages more quickly. The expected wage path will now be more muted and delayed than the RBA had previously expected.

In contrast, if the Democratic party manages to coalesce around a large stimulus package of some form, the US economy is expected to push through the pre-covid trajectory, a level generally regarded as running at full steam as it was, and into levels that exceed estimates of sustainable full capacity. The US economy will be running hot:

The US is expected to have a much tighter labour market than Australia in the coming years. They are seeking to create an inclusive employment outcome, are concerned to re-anchor inflation expectations and trying to create a buffer against the Effective Lower Bound of monetary policy. The tightness of the labour market will be exacerbated by the retirements of several older members of the workforce. There may also be a significant mismatch in the skills required in the new, post-covid economy, relative to what is currently available. A higher level of mismatch implies that tension in the labour force will be reached at a lower level of economic activity.

In contrast, the unemployment rate in Australia remains very low. At 4.6% in September, despite extended lockdowns in NSW and Victoria, it highlights that there remains a high degree of ongoing connection between workers and employers. The level of mismatch looks lower here than in the US.

When looking at economic output and expected labour market conditions, the cash path for the US should also exceed Australia’s.

RBA Policy Rules

The RBA changed tack on its approach to monetary policy in October last year when it altered the policy rules to reduce the role for inflation forecasts. Now, it has committed itself not to increase the cash rate until actual (core) inflation is sustainably within the 2-3% target range. The concept of sustainably relates to a reasonably amorphous level of wage growth which should be above that level and is generally thought likely to occur when unemployment reaches into the low-4s again. The RBA will want to see wage growth and core inflation at target levels for around 12 months before raising rates.

Even under the RBA’s assumptions of border re-opening in June next year, the prospects of unemployment reaching levels which would start to spark a controlled wage-price cycle looked unlikely to commence in earnest before early 2023. This prospect has become more unlikely with foreign labour supply increasing much sooner than had been expected. Yet, recent moves have brought the expected date of lift-off even further forward to around September 2022.

On the large contours, Governor Lowe’s reaction to a market which appears to disregard the guidance by quite so much seems reasonable, especially given the RBA’s economic projections aren’t wildly different to consensus. To add some spice, his term ends in September 2023 which might provide further resolve to ingrain credibility in the new policy rules as his legacy. Any decision to step away from long-held guidance can be left to the next Guy.

What else might be driving market expectations for higher rates in the nearer term?

APRA and Fixed Rate Mortgages

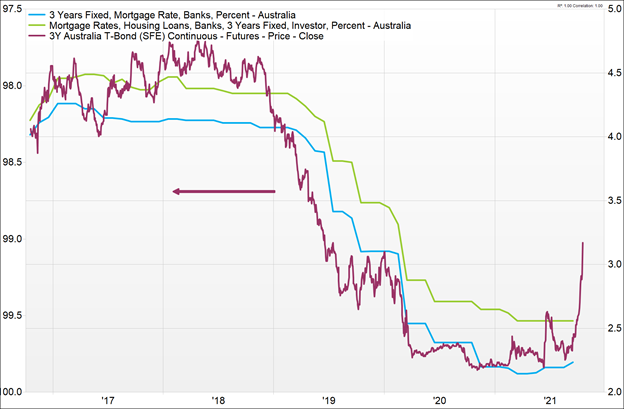

It is true that low cash rates have fuelled a strong property market and financial stability considerations have emerged, albeit of a long-range precautionary nature. Some market participants arguing for an earlier tightening assign significant weight to the imperative to prevent an asset bubble. Nonetheless, with the RBA repeatedly saying it has no role in targeting property prices, APRA has appropriately announced its presence on the matter again by raising the buffers which lenders must use to assess affordability by 50bps. Although this will not have a large impact immediately, further capital adequacy rules are arriving next year which will make it less attractive for banks to lend to highly levered investors.

Additionally, a growing trend had emerged amongst borrowers who increasingly preferred fixed rate loans. In its latest half-year results, 44% of CBAs housing loans were made on a fixed basis. Unlike APRA’s buffer variation, the current market pricing for the rate path will definitely be felt more broadly and impact loan volumes:

The RBA is not compelled to change its intended cash path to prevent a housing bubble. The appropriate regulatory response and concern that this might become the RBA’s role being priced into the market will help achieve those aims as it is. If things don’t change, fixed mortgage rates will be back to pre-covid levels before long.

Demand for Foreign Capital and the AUD

At times when Australia requires a lot of foreign capital, higher real interest rates are required to provide adequate incentive. However, Australia has been running sizeable current account surpluses and, with the Term Funding Facility providing excess funding for the banks, has limited need to reach for foreign capital in the near term. Our burgeoning superannuation savings market provides a significant source of capital which, if anything, is being increasingly forced to look for opportunities offshore.

There is a structural shortfall in energy investment as the world grapples with plans for an energy transition. The outcomes of an incomplete planning process are evident in energy and commodity prices today. Demand for Australian coal and LNG exports, which drove the Terms of Trade upwards even as Iron Ore prices declined, is set to remain strong for the next several years and this will contain the need to require large net external financing, albeit our banks will need to refinance their Term Fund Facility draws in coming years as well.

Additionally, our bonds are attractive to European and Japanese investors due to the relative slope of our yield curves.

The RBA has not indicated that a material mispricing in the exchange rates exists and is not explicitly seeking to raise the level of the AUD by word or deed. In fact, one of the benefits of the QE program is that it reduces the level of the AUD. With this being fully tapered next year, the RBA will be in no hurry to give foreign capital a reason to reduce our external competitiveness, before our recovery is complete, by raising rates.

It's a puzzle

We have examined the usual suspects, and some other less usual ones like drift in the r-star (equilibrium real interest rate) and risk-based concepts, which have generally explained the differences in the cash paths in the past. We have not found a compelling argument as to why the market would be ignoring the RBA’s guidance to the extent that it is beyond simply believing the policy rules are inappropriate and will shortly be ignored by the RBA itself, or on the expectation that a significant shift towards wage-price rigidity will emerge imminently.

Whilst the OECD has called for a review of the RBA, the main criticism would be the fact that inflation has tended to undershoot targets. That would hardly be remedied by raising rates. The formation of widespread wage-price rigidity is also completely absent at present. It is possible that the inflation target might be revised downwards, in line with other major central banks, but a lot of weight would need to be placed on this speculative outcome. Inflation outcomes are well within target bands, our sovereign rating is AAA, we have no difficulty of attracting foreign capital, and walking away from a practical policy which was formulated only in October last year seems far-fetched when no change to the key leadership is likely for years.

We believe the cash path for Australia should be below the US for maturities up to 3 years.

Further, we have yet to identify a convincing rationale that explains why the market behaves as if the RBA were the Fed’s Deputy Sherriff.

What we’re doing

At Realm, our moderate-risk target, multi asset-class credit portfolio utilises bond exposures to improve risk-adjusted returns over a cycle. In general, bonds and credit exhibit a slightly negative correlation. With credit spreads being tight and the yield curve now relatively steep by comparison, there is still some role for bonds. Nonetheless, our interest rate duration has been at the lowest end of our general practice for several months.

However, as QE is being tapered, the correlation has a greater risk of becoming positive. This is especially so given the possibilities of a moderately disorderly process should a non-transitory inflation narrative fully take hold. Although unlikely, the ECB has reiterated that the liquidity risk of non-bank financial institutions could become elevated and we may see a sell-off in bonds and credit at the same time as a pro-cyclic pattern of trade develops similarly to the most dysfunctional periods of March 2020.

Due to the lack of experience with a recovery of this nature, mixed with severe disruptions in the physical plumbing of our economy, imaginations can run far in different directions. There is no QE for an energy shortfall or repo facility to ease port congestion. Interestingly, in the last week, the market has begun to price the possibility that the Fed may overdo its tightening cycle. This is taking place around a year before the first step is expected to be taken! As imaginations and dislocations tend to run wildest in long-duration assets, and they still appear expensive, there is less of a role for long-dated bonds than usual.

Nonetheless, we believe the market’s disregard for the RBA’s guidance has become extreme. It appears to be substituting the US situation for the domestic circumstance, which is an unusual development. This would be shattered if, say, China’s financial system were to become unstable or construction was slowed significantly whether due to energy shortages or measured policy directive. Finally, a large surge in the rate path following a surprisingly high inflation outcome in New Zealand has stretched the divergence even more.

If you believe the RBA has any credibility in pursuing its revised policy commitment, the short end of the bond curve looks like a healthy place to be if duration has a role in your portfolio.

One thing to watch closely would be the yield on the Australian April 2024 bond. This was the focal point of the RBA’s efforts to anchor expectations that interest rates would not be lifted before 2024. The target yield was set at 0.1% in November 2020. If the RBA seeks to step away from the timeline it has communicated, it may show up through this indicator if the yield to maturity is not defended as purposefully. However, in the last day, the RBA has moved to defend it via a technical adjustment to the borrowing rate which must be paid by short-sellers of this bond. Perhaps a hint of more to come?

Realm is your partner

Our clients are our lifeblood. With deep experience investing in Australian Credit and Fixed Income markets, Realm is result-oriented. We are always focused on delivering client outcomes. Click the 'FOLLOW' button below to receive our insights.