What to do when your holding gets crushed!

(Editor's Note: While this article was first published in 2018, we feel this blast from the past is timely given recent market conditions).

With the NASDAQ down more than 4% overnight, it's likely to be a rough day on the ASX today. Back in 2016, Livewire reached out to a selection of fund managers to understand the process they follow if a stock in their portfolio suffers a significant fall. Given the likely volatility ahead, we thought it would be a good time to review their responses.

As discussed in some of our contributors’ responses, the decisions you make after a stock has dropped are essential to your long-term performance. While the processes followed vary significantly between managers, what stands out is that the processes are pre-defined and prepared well in advance. This demonstrates that investors need to be proactive rather than reactive. Click the link below to access the full responses from Nathan Bell, Steve Johnson, Chad Slater, Chris Prunty, and Simon Bonouvrie.

What matters is today

Steve Johnson, Chief Investment Officer, Forager Funds

My first step is to wipe the slate clean. Forget I own it. Forget the share price has fallen. And try and take the emotion out of it. It shouldn't matter whether a stock has fallen, risen, or not moved for the past few years. What matters is the opportunity that is in front of you today. Given all of the available information, do I want to own the stock at today's price? And, if so, how much of the portfolio do I want to have invested in it?

Are you more likely to be a seller or a buyer after the drop?

The answer to that question determines whether I am buying the stock, selling part of our holding or selling the lot. As value investors, more often than not we end up buying a stock that has fallen because it is cheaper than it was. But it's important not to be blindly contrarian. Sometimes new information can materially change our estimate of a business's value.

Watch the trend

Simon Bonouvrie, Portfolio Manager, Cadence Capital

At Cadence, we have a process of scaling into and out of stock positions. When a price trend in a stock turns and moves materially off a previous high, we will start selling the position. This process of scaling out of the position continues as the stock trends lower. We also institute a hard stop discipline when the stock falls a material amount from our average cost price. So generally speaking, we sell stock as the price moves lower with a view to possibly exiting the position after a significant price drop.

We hold the view that stocks like to trend; therefore, we don’t add to a falling position. If the fundamentals of a stock have not deteriorated, or in-fact improved, and the stock price starts to recover after a significant fall then we may look to scale back into a position or initiate a new position. We need to see a technical price chart-bottoming pattern before considering buying the stock. We will only invest once we think the price trend has reversed and is heading back up.

A pre-defined process works best

Chad Slater, Joint Chief Investment Officer, Morphic Asset Management

Morphic follows a rules-based policy for stocks that have lost the firm money. Empirical evidence suggests that a pre-defined process deals with these situations better than allowing complete discretion. Prior to initiating a position, the analyst is required to identify not only risks, but also the likely impact of that risk; its probability, and their confidence interval. This gives an expected loss under different scenarios and allows price levels to be pre-defined. These levels are crosschecked based on the volatility of the stock – otherwise, you run the risk of exiting the stock on “noise”. Sizing is what drops out of the process at the end of this.

With loss tolerance already defined, the PM needs to decide if they want to incept fully at the start or whether to keep some “up their sleeve” to take advantage of a risk event to add. As a rough rule of thumb, a “statistically significant move” and/or an event that wasn’t forecast would result in exiting rather than adding to the position.

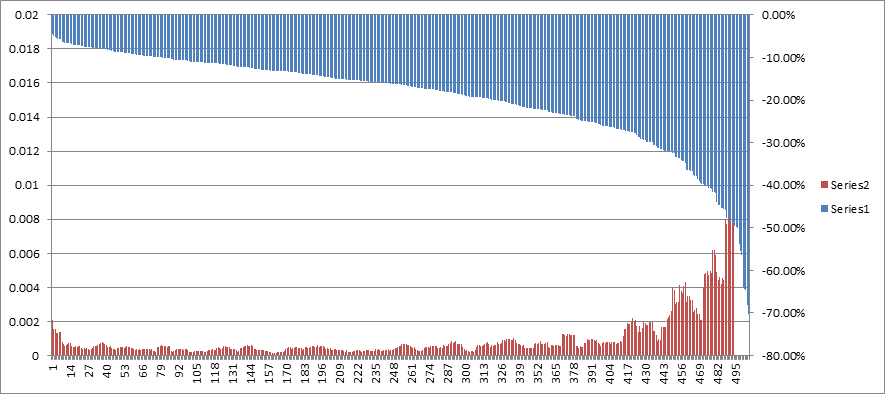

Chart Below: Distribution of maximum drawdowns of the S&P 500 stocks in 2015: Beyond 20% the relationship becomes non-linear – setting loss levels reduces the risk of owning (a lot of) a stock where this happens to you.

Focus on the facts, remain unemotional

Nathan Bell, Portfolio Manager, InvestSmart Group

Whenever we buy a stock, we have a very clear rationale for it. Although you can analyse all sorts of financial and industry details, the investment case comes down to just two or three factors. When a stock we own falls steeply our job is to work out whether our investment case has been impaired. Often the answer is an easy 'No', so we quickly move on. Sometimes it may require analysing new information, which could involve one or more analysts. The important thing about your process is to act quickly without being impetuous and making the wrong decision. US fund manager Richard Pzena once said that the decision you make after a stock has fallen significantly has the biggest impact on your returns. Do you buy more, sell or hold on, based on the share price and your current estimate of intrinsic value (not what you paid for the stock). The key to this process is remaining unemotional, accepting responsibility for the decisions that need to be made, being open-minded, not passing blame and making your decision based on the facts.

Know when to run

Chris Prunty, Principal and Portfolio Manager, QVG Capital

As Kenny Rogers says; you've got to know when to hold ‘em. Know when to fold ‘em. Know when to walk away, know when to run. When a stock falls materially – say 20% - then answering the hold, fold or run question correctly is what distinguishes the good, the bad and the ugly investors. We are not price momentum players; meaning we don’t automatically buy strength and sell weakness. Rather share price movements – especially those on the downside – act as a catalyst for us to review our assumptions around the operating performance of the companies we own. Broadly speaking if the balance sheet is improving and the company’s earnings are meeting expectations then there’s no reason to sell if a stock has fallen and it may be a buy. We sell when the share price has fallen if we come to the view the stock is anticipating or reacting to, an earnings downgrade. Short-term share price movements are as much of a mystery to us as anyone. In the medium term, there is no mystery; share prices follow earnings revisions.

2 contributors mentioned