Why TDM is playing defence in the current market

The idea that higher valuations necessitate more heroic assumptions, or lower future return expectations, to justify holding a position is an investing truism.

But what do investors need to believe in order to generate an adequate level of return in the current equity market environment? Our firm belief is that investors can’t just own an amazing business, regardless of valuation. And now, with markets at all-time highs, this holds true and is shaping how we are thinking about our portfolio construction at TDM.

The following wire is an abridged version of a memo Andy Simon and I sent to our clients in the middle of February 2021. In it we unpick the prevailing sentiment that valuations don’t matter; reveal how we balance “offence” and “defence”; and explain what we would have to believe from here if we were to want to buy high-growth businesses at current valuations.

What do investors need to believe from here?

As a rule, we don’t like talking about the overall market and its valuations. We obsess every day about our businesses, how they’re performing and how we can help them achieve better outcomes.

If our businesses perform in line with our five-year expectations from a revenue and earnings perspective, then we have confidence that we will compound our capital at north of 25% per annum, the hurdle we have cleared now for 16 years.

With this business-owner mindset, we don’t need to worry about daily fluctuations in share prices — in fact, only one person in our office has any idea what the market is doing on any given day, and that is our wonderful head of trading, Anna.

With everything going on in the world and with markets at record highs, we felt the need to help clients understand how we are currently thinking about the portfolio and the overall markets.

Some of us are now old enough to say we were investing at other strange times, such as:

- The tech bubble bursting in 1999 / 2000 — the Nasdaq fell approx. 80% from peak to trough and took 15 years to get back past the previous peak;

- September 11 terrorist attacks — most indexes fell approx. 15% over 5 trading days;

- Global financial crisis of 2007–2009 — from the peak in October 2007, the major US indexes fell over 55% to the trough in March 2009 before taking another three to five years to get back to previous highs;

- European debt crisis of 2011 — major US indexes fell between 19% and 30% over a six month period;

- Tech meltdown of March 2016 — the overall Nasdaq fell circa 20% in two months, but we can remember clearly the small- to mid-cap technology businesses that we follow closely generally fell circa 50% over the same period (as an aside — still to this day, we can’t work out what the catalyst for this decline was!);

- COVID-19 in March 2020 — of course, more recently, the 30% to 40% fall in 33 days as the world went into lockdown.

We think the current market environment in our investable universe of growth companies — let’s call it the “mid-pandemic world of cheap money and crazy valuations” will also end up on this list – we just don’t know when. (And yes, we have the right to rename this period once we know more!).

When we think back through the different periods, we would probably liken the current period to 1999–2000 more than any other. We are certainly not at the extremities of what we experienced in 2000 when many technology businesses had very large valuations but close to no revenue. It seemed insane at the time and history has proven this to be true. Conversely, this time around the most highly valued businesses have amazing and easy to understand business models, and large and very fast-growing revenue bases. Because of this, you can have some conviction as to what the business looks like in the medium term— but the point of our comparison is that what people are willing to pay for these businesses is at levels not seen since 2000.

There is a growing sentiment among many professional investors that the only thing that matters in a low-interest rate, low economic growth environment is the company’s growth rate and that valuations are a secondary thought. We have heard several professional managers argue that the price you pay actually doesn’t matter in these amazing, fast-growing businesses.

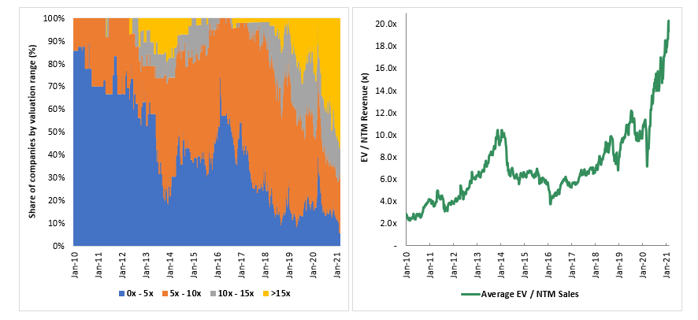

To help show how software-as-a-service (SaaS) valuations have changed over the last 10 years, we have charted below global SaaS businesses using Enterprise Value (EV) / Next Twelve Months (NTM) Revenue multiple broken into cohorts based on the valuation multiple bands.

Some interesting colour in the valuation expansion discussion:

- Finding a business trading on 15-times revenue used to be rare, now more than 55% of all these businesses exceed this.

- The average multiple from 2010 to 2015 for all SaaS businesses on this list is just 5.5-times, and 7-times from 2010 to 2020. This is compared to today’s average of 20-times.

We are also seeing a variety of behaviours reminiscent of those from 1999 / 2000, which many believed were once-in-a-lifetime phenomena;

- It seems increasingly normal to see IPOs double from their issue price on day one

- January trading volumes in the US up 90% year-on-year (Gamestop, anyone?)

- Options trading in 2020 up 50% year-on-year

- Margin lending in the US is at a level not seen since 2008

And of course, how can we not include the $73 billion raised by blank cheque (SPAC) companies in 2020. The famous tautology “it is like Deja vu all over again” is ringing in our ears.

Oh, and we almost forgot: global equity inflows were US$58 billion in mid-February. This compares to the last 10 years, where inflows generally ranged from negative US$10 billion to positive US$10 billion.

What does this mean for our portfolio?

In such times, we are always drawn to the mental model that likens investing and portfolio management to that of a great football team manager who understands the importance of balancing “offence” with “defence”. This is particularly pertinent to us — there are only ever finite spots (15 companies) available in our portfolio.

A key part of our role as capital allocators is knowing when to play offence and when to play defence.

Right now, we are playing defence, with a strong preference for a larger cash weighting in the portfolio over deploying capital. This mental model is not new. It has often been spoken about by revered investor Howard Marks (of Oaktree Capital fame).

“ … we want to have a lot of offence when prices are low, psychology is depressed and the outlook is bad to most people but we don’t think it’s so bad. And we want to have a defence when prices are high, psychology is buoyant and everybody sees a brilliant future, and we don’t think the future may live up.”

The idea that higher valuations necessitate more heroic assumptions (or lower future return expectations) to justify holding a position is an investing truism. We always like to focus our attention on what any investor needs to believe to generate an adequate return for holding an investment from here, with the key question being, “if I bought today, what future returns can I expect?”. We strongly believe you can’t just own an amazing business regardless of valuation.

We idolised Warren Buffett in our teenage years — his philosophy around backing outstanding management teams over the very long term has been the foundation of our investment philosophy. However, there has always been one thing we don’t agree with — that you should never sell your shares in great businesses.

A few examples to help explain our perspective:

The Coca Cola Company, one of Buffet’s most famous investments …

A decade after his post-1987 market crash purchase, Coke was trading at US$35, compared with around US$50 today. Buffett made 10-times his money in the first decade he held the investment (or 25% a year) but only 16-times his money (including dividends) over a 30-year hold (or the equivalent of 10% a year). He still owns shares. The opportunity cost of holding through the last two decades has been extreme, considering his high rates of return over long periods.

Microsoft or Walmart spring to mind when we think of high-quality businesses with long growth duration. Since they listed in 1986 and 1970, respectively, both have compounded shareholder returns at 25% and 20% a year. But both are also great examples of what can happen if your future growth is already baked into your valuation and, despite near perfect execution, an incoming investor doesn’t make an adequate return.

For both Microsoft and Walmart, their share price history can be broken into two distinct periods: from IPO to 2000, and then from 2000 for the next decade and a half.

From listing to 2000, investors in either

of these businesses had multi-hundred baggers on their hands. What dreams are

made of! However, for the next 16 years from 2000 to 2016 both businesses went

nowhere from a share price perspective. During this time, both companies grew

revenue and earnings strongly — Walmart grew revenue by almost three times, and earnings

per share by four times, while Microsoft grew revenue by over four times and earnings per share

by almost three times. And yet, if you had held throughout this period as a shareholder,

you would have not received a return reflecting this. Valuation matters.

Rather than buying or holding a business regardless of valuation, we as an investment team are continuously assessing and asking ourselves the question —' what does this business need to achieve operationally and financially for us to generate a greater than 20% pa return on our investment over the next 5 to 10 years’ and determine if this hurdle is achievable for management to jump over under a reasonable set of assumptions.

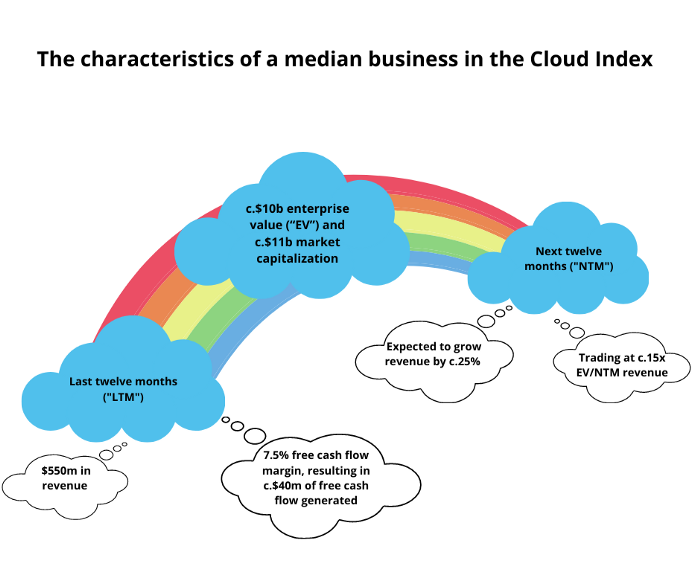

To

help explain how we think about this concept and investing at this very moment,

we can utilise the

Bessemer Venture Partners (“BVP”) Emerging Cloud Comp Index (“the BVP Index”), a publicly available index of 54 US-listed

SaaS companies ranging in size from less than $2b to close to $300b in market

capitalization. The characteristics of this index help define a “typical”

growth technology business today and is a good proxy for our investable

universe.

Source: Supplied.

But can we achieve our returns?

The question now is, what do we need to believe to achieve 20% returns over the next ten years for the hypothetical business laid out above? The answer: we would need to be comfortable making some pretty heroic assumptions!

Source: Supplied.

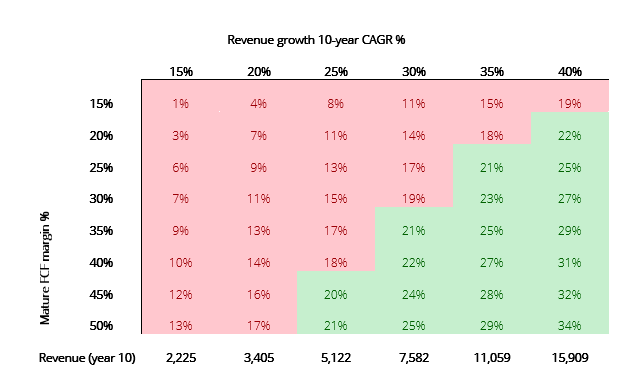

Over the next decade, we need to assume the business can compound revenue at approximately 30% a year to more than $7.5 billion, and generate greater than $2 billion in free cash flow (FCF). This means growing the revenue base 13-times from $550 million today and FCF 50-times from $40 million today. This is reflected in the table below, showing expected 10-year returns under different revenue growth rates and FCF margins.

Figure 1: Expected 10-year annual returns for the median business in the BVP SaaS Index relative to forecast revenue growth and free cash flow margin. We are assuming an 25x FCF margin exit multiple (7.5x NTM revenue at 30% FCF margin). Source: Supplied.

To achieve these assumptions, the resulting hypothetical business places itself in very rarefied air indeed. We can count on one hand the number of software businesses that have achieved this growth feat to date.

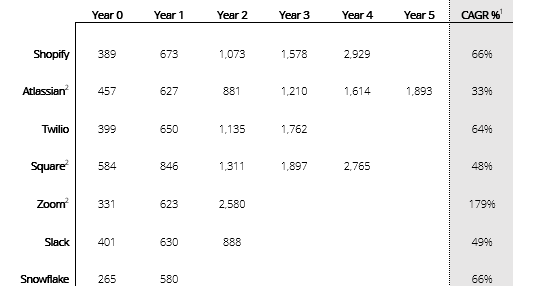

The table (figure 2 below) shows the revenue trajectory for a group of the largest and most successful US software businesses over a 10-year period. The starting period, year zero, corresponds to the period when their revenue was approximately in-line with that of the median business in the BVP index of $550m.

Of the nine businesses in this list, just two have achieved a greater than 30% compound annual growth rate over a 10-year period, being Microsoft and Salesforce.

Workday, ServiceNow and Palo Alto Networks have not yet reached the 10-year mark. But if they can sustain current growth rates, they are on track to clear the hurdle.

The other businesses on this list — Adobe, Intuit, Autodesk and Akamai — had strong growth in the early years but experienced a material deceleration at some point in their development and stagnated. In short, to achieve our return hurdle for the median business on the BVP Index today we need to assume performance in-line with five of the most successful software businesses of all time. This is an extremely high bar to clear.

Source: Supplied.

Having said all of that, there is no doubt that the next 10 years will be different from the last, and getting to more than $7 billion of revenue will be achieved by many more businesses than just five (two officially, but assuming Workday, ServiceNow and Palo Alto will get there).

Digital transformation has been brought forward and there have never been more public high-quality, high-growth technology businesses. In other words, the bar to achieving this type of performance today is lower than it has ever been previously.

The table below shows a group of less mature listed US technology businesses that are on a path to compounding revenue at 30% p.a. over a 10-year period from a circa US$500m revenue start.

Source: Supplied.

However, this is already reflected in their valuations, with these businesses trading at a staggering average EV / NTM revenue of close to 40-times. While these businesses are growing revenue at an average of more than 50% today, to generate our required 20% a year return over the long-term, they must sustain revenue growth of more than 50% a year for the full 10-year period (equating to $40 billion of revenue in year 10)! Not even Microsoft has achieved this hurdle with $15 billion of revenue and a 38% 10-year CAGR over the period. And if we found the next Microsoft, we would hope to earn a lot more than 20% p.a. over a 10-year period.

There is one potential flaw in the above expectations analysis: the assumption of maturity in year 10. What if the business is not at maturity in 10 years but still growing at high rates? Surely it would be worth more than 25-times free cash flow (equivalent to 7.5-times revenue at a 30% FCF margin) at that point in time?

This is indeed a reasonable argument. The problem is 10 years is a long time by any stretch. Forecasting one year out is hard enough, but so many things can happen (positive and negative) over a decade, making any degree of certainty over this period near-impossible.

While there is most certainly a scenario where the business achieves the high growth hurdle and continues growing at a high rate beyond year 10, there are also many scenarios where this does not happen, and the business “hits a wall” at some point in this timeframe.

The key point is, if we must assume the high hurdle scenario to achieve our target returns, there is zero margin of safety in the investment.

Where we are today…

There has never been a greater opportunity set of fantastic high growth businesses. But the vast majority of these businesses are already pricing in extremely rosy expectations for the future. This may happen or it may not. We don’t know. What we do know is this — we would much rather invest aggressively when we don’t have to know. Until then, we are happy to be patient and play defence.

As is so often the case, we will leave the final word to Warren Buffett:

“Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.”

Footnotes:

Full assumptions in regards to what hurdle needs to be jumped over to achieve a 20% return from here;

1. We are looking at 10-year returns based on a valuation of the business in year 10;

2. The business reaches maturity in year 10, defined as growing in-line with nominal GDP;

3. At maturity the business will generate a 30% FCF margin;

4. A “through the cycle” valuation multiple for a mature business of this nature is 25x NTM free cash flow (equates to 7.5x NTM revenue at a 30% FCF margin);

5. No dilution from share issuance;

6. Starting cash on balance sheet of $1 billion (c.10% of market cap);

7. All free cash flow generated is retained in the business.

Short form footnotes referred to in tables

1/ Compound annual growth rate from year 0 to the final revenue year in the table

2/ As at 20 January 2021. Note that SQ is calculated on a net revenue basis to be more consistent with the revenue of the other businesses in the list

Not already a Livewire member?

Sign up today to get free access to investment ideas and strategies from Australia’s leading investors.

3 topics

.jpg)

.jpg)