Why the way we're building portfolios is broken: Luke Laretive

A couple of weeks ago, I invited Luke Laretive, founder of Seneca Financial Solutions, to take part in a thought experiment: building a 10-investment, long-term growth portfolio to illustrate how an expert might approach growth investing.

Several advisers embraced the challenge and shared thoughtful submissions. While recognising that a 10-asset portfolio is a simplified, hypothetical exercise, Luke saw it as an opportunity to raise a broader concern: that portfolio construction is too often presented to retail investors without sufficient structure, discipline, or strategic intent.

“I’m particularly scathing and critical of (sadly, most) advisers. They think a couple of index ETFs whacked together with a few pray-and-spray pet stocks they look at once a quarter, an active fund manager (or two) who shouts them a round of golf, and some overpriced thematic product chasing the latest hot sector — all benchmarked to nothing — is ‘high-net-worth wealth management'," he says.

While his comments may raise eyebrows, they also prompt reflection. What’s wrong with the way portfolios are commonly built? And how does Luke believe it should be done instead?

In this Q&A, he outlines his concerns — and shares his approach to building more intentional, evidence-based portfolios.

You mentioned you’re “particularly scathing and critical” of how portfolios are built. What exactly do you see as the problem here?

Why am I critical of this? Because clients deserve better. It reflects poorly on the profession.

I don’t think it’s acceptable that advisers just buy an ETF, a couple of active funds, and a few direct shares, and review it twice a year. I don’t think it’s fair that clients are misled or misdirected by their adviser rather than educated.

It’s poor process that lacks any real academic rigour. Particularly if it’s implemented inconsistently and lacks accountability for the decisions made — or a feedback loop for constant improvement.

I think it’s misleading the way the media rarely reports returns on an apples and apples basis. It’s confusing enough for people trying to make the best decision for their family.

Does core-satellite investing help people manage risk — or does it just let them feel clever when their bets pay off and shrug off the ones that don’t?

We think this approach is popular because it emotionally enables people’s desire to gamble with their wealth - they can write off bad decisions as “small weight” or “just having fun” while they can get excited and think they are clever when they make good stock/manager picks.

In our opinion, this lacks accountability and is completely inconsistent with our investment approach – we want to exploit other people’s emotional biases while resisting our own (using data to help us.)

Core/satellite thinking is consistent with behavioural finance academia around “mental accounting” (explained in point #3 here) – treating a dollar in one bucket as different to a dollar in another. It’s common practice, but completely irrational.

The solution is to design an investment strategy and your neutral portfolio settings, and then measure your tilts through time.

That doesn’t mean buy and hold. It means every day your adviser is ensuring your portfolio is optimally invested. Adjustments shouldn’t be dictated by their busy calendar, but by the opportunities that regularly arise in the global markets.

We're obviously seeing an enormous shift to passive funds. Investors want to keep their costs down, and advisers want to market lower-fee offerings. But you believe this is short-sighted - why?

We focus on after-fee outcomes (i.e. I’d rather get a 20% return after paying 10% in fees than a 9.7% return after paying 0.3% in fees). If a manager cannot add value for us after fees, we don’t use them.

As long as the fees are:

- Competitive with relevant alternatives, and

- Fair in the way they are calculated (correct hurdle for performance fees, high watermark etc.)

Then we do not focus on avoiding fees. We focus on generating exceptional returns for the level of risk each client is able to accept. I also wrote recently about why “fee budgets” don’t make any sense to me.

How do you select managers for your portfolios?

We select active managers where we assess it's likely to add incremental value to a client's portfolio – either in reducing risk, or increasing expected return. When we do this we think in terms of “systematic” vs “discretionary”.

- An index or passive fund is just a systematically weighted portfolio that allocates capital based on the size of the company, relative to its peers (typically, geographic peers.)

- There are other systematic strategies that use different rules to allocate capital (typically called a “quant fund”, Renaissance Technologies is the most famous.)

- There are other strategies where capital is allocated not based on pre-defined rules but on at the fund portfolio manager’s discretion. This is your ‘normal’ active fund operating in a particular asset class or geography.

I get your criticism of the general portfolio construction process used by the masses. What's a better approach?

The starting point for us would be to define a reference portfolio. This isn’t necessarily what we invest in; it's just a basic, cheap, fast, and adequate solution.

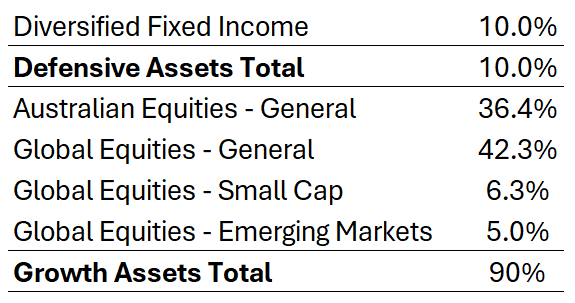

As an illustrative example, I’ve just run with Vanguard Diversified High Growth Index ETF (ASX: VDHG) as our reference portfolio for an investor with a high growth objective. I've summarised the strategy's weightings below.

In summary, what we get with VDHG is:

- 90% shares, 10% bonds

- 53% global shares incl. 6% smalls and 5% emerging markets specific.

- 36% Australian shares

- 23% of the portfolio is AUD hedged.

- Cost 0.27% p.a outside super. 0.54% inside super.

That becomes your neutral, no-views, no-active-management baseline, and then we seek to add value from there.

How do you define “adding value”?

That depends on the objectives. What are we trying to do here from that baseline? Is it simply increasing expected return? Decreasing volatility? Maximising Sharpe ratio? It’s corny but very on brand for us, if you don’t know which port you are sailing to, no wind is favourable.

I like to explain it to clients like this: you can pick either maximise return for an agreed level of risk, or minimise risk for an agreed level of return. That’s the starting point. Everything flows from that.

Then you can ask questions like:

- Can I adjust the growth/defensive split?

- Should I tilt within existing asset classes — like size, geography, style?

- Should I introduce new sub-asset classes — like long/short equity, private debt, VC, or real assets?

- Should I hedge more or less?

But the most important question is: How do I make those decisions?

- What drives them?

- What’s the scope?

- What are the tilt parameters?

- How do I measure effectiveness?

- What’s the plan if things go wrong?

If you're constantly changing the inputs and criteria, how do you know what works and what doesn't?

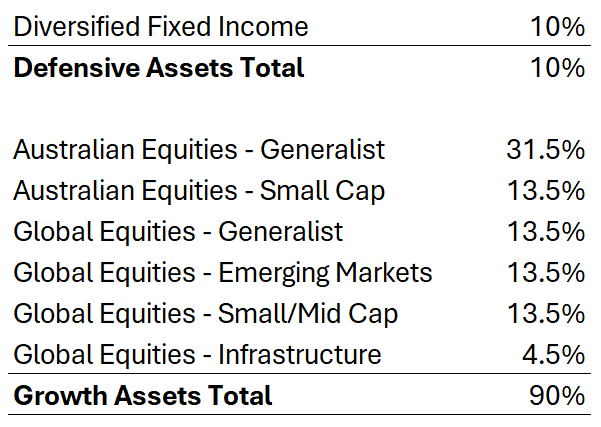

How is this approach implemented at Seneca?

Our Investment Committee (IC) meets monthly to review all our investments and discuss potential changes.

We’ve got a big workbook that gets turned into a meeting pack — with all the macro stuff you’d expect: charts, data points, excerpts from research. Each decision has ±% maximum tilt and a minimum % change step.

Every portfolio has a specific mandate, a specific benchmark, and a clear set of rules. Our reference portfolio is consistent across all clients with the same risk profile – it’s simply the benchmark for each asset class portfolio, at the asset allocation percentage weight.

If we make a change, it’s implemented across the board — all clients get the change at the same time, at the same price. It’s a completely egalitarian environment at Seneca. There’s no friction between IC decisions and real-world execution.

Where are you positioned right now?

Relative to the respective benchmarks, we are overweight:

- Equities: Smalls, quality (both locally and internationally)

- Equities & fixed income: Near maximum overweight emerging markets/non-US

- Fixed income: Slightly longer duration, higher yield than benchmarks (a bit more rate sensitivity / benefit from falling inflation)

- Absolute return: Benchmark less relevant (CPI +4%) but relative to peer group we are considerably less correlated to markets (portfolio = 5% r2, peer group = 60% r2.)

These tilts are essential and add value, but we find that the most significant contribution the IC makes is in manager selection.

Which managers have been the most important source of added value?

A few highlights, to 31 March, after fees:

- Absolute Return: Pyrford Global Absolute Return +25.81% over last 3 years

- Fixed Income: Mutual High Yield +32.13% over last 3 years.

- Fixed Income: Colchester Emerging Market Bond Fund +35.11% over last 3 years.

- Global Equities: GQG Partners Global Equity +16.06% p.a. over last 3 years.

- Australian Equities: FS-RQI Australian Share Value +22.97% over last 3 years (low-tracking error, systematic strategy to complement our discretionary, high-tracking error strategies elsewhere in our Australian equities SMA).

And where are your tilts right now?

Our view is that incremental outperformance from here, in equities, will be driven by 3 specific exposures.

1. Australian small companies

We invest directly on behalf of our wholesale clients via Seneca Australian Small Companies Fund. Our fund is up 28.33% after fees, over the last 12 months, ~+25% ahead of the benchmark.

We see this sector as a sustainable source of outperformance due to vagaries of the benchmark construction, the discrete opportunities we’ve identified across our portfolio and a reversion to median performance across smaller companies on the ASX more broadly, relative to large caps.

We manage direct portfolios of shares in Australian equities because we feel there is a reasonable likelihood of us adding after-fee value for our clients in this asset class – this is where we’ve built our careers and experience.

We feel a lot less comfortable picking stocks in emerging markets or trying to gain an edge buying direct bonds from a European corporate, for example. Though we think there’s value and diversification benefits from investing in these asset classes – we just aren’t experts at doing it, but there are people, who we can employ for clients, who are.

2. Emerging markets and non-US equities

On valuation grounds, we are overweight emerging markets. The Seneca Global Equity SMA currently utilises the GQG Emerging Markets Fund which is tilted to India/South America and the FSSA Emerging Markets Fund which is more focused on East Asia.

3. Global small-and-mid-caps (SMIDs)

Other developed markets offer similar opportunities in SMIDs Australia. We are overweight global SMIDs in the Seneca Global Equity SMA. We are currently using Fairlight Global SMID & Bell Global Emerging Companies Fund.

What framework would you give self-directed investors who want to manage their portfolios more dynamically?

Start with a clear objective. And not just ‘earn 12% after fees’ — I mean a real, thoughtful strategy. Ask yourself:

- What asset classes will I invest in?

- What’s my baseline asset allocation to each?

- When, how and why will I make changes?

- Will I use funds or invest directly? Why? Why not?

- Will I go active or passive? What would make me change?

- What’s my investable universe?

- What’s a fair and reasonable benchmark?

- How will I measure success?

These are basic questions — but in my experience, most people can’t answer them.

These are also really good questions for your current adviser. They should be able to answer them specifically and outline the basis for these decisions.

"This is particularly relevant if your adviser uses the words 'personalised' or 'bespoke' in the way they describe their services to you."

2 topics

1 fund mentioned

1 contributor mentioned