Why valuations don’t drive stocks

Financial gospel suggests that when the market is trading at high price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios—or other metrics like price-to-sales or price-to-book—it is fully valued (or even excessively valued), which means there is little upside, making it less likely to appreciate. Valuation metrics fit our intuitive notion to buy low and sell high. For example, if the P/E using trailing 12-month earnings for the MSCI World Index—a widely watched global developed market stock index—hits 30, which it rarely reaches (the long-term historical average is 18.3), then it may appear to be a sensible time to exit stocks.[i] As the thinking goes from pundits Fisher Investments Australia reviews, why buy stocks when the likelihood valuations go even higher is so slim? By the same token, say stocks slip below 15 P/E, a historically low valuation measure. Supposedly at that threshold, investors would have more to gain.

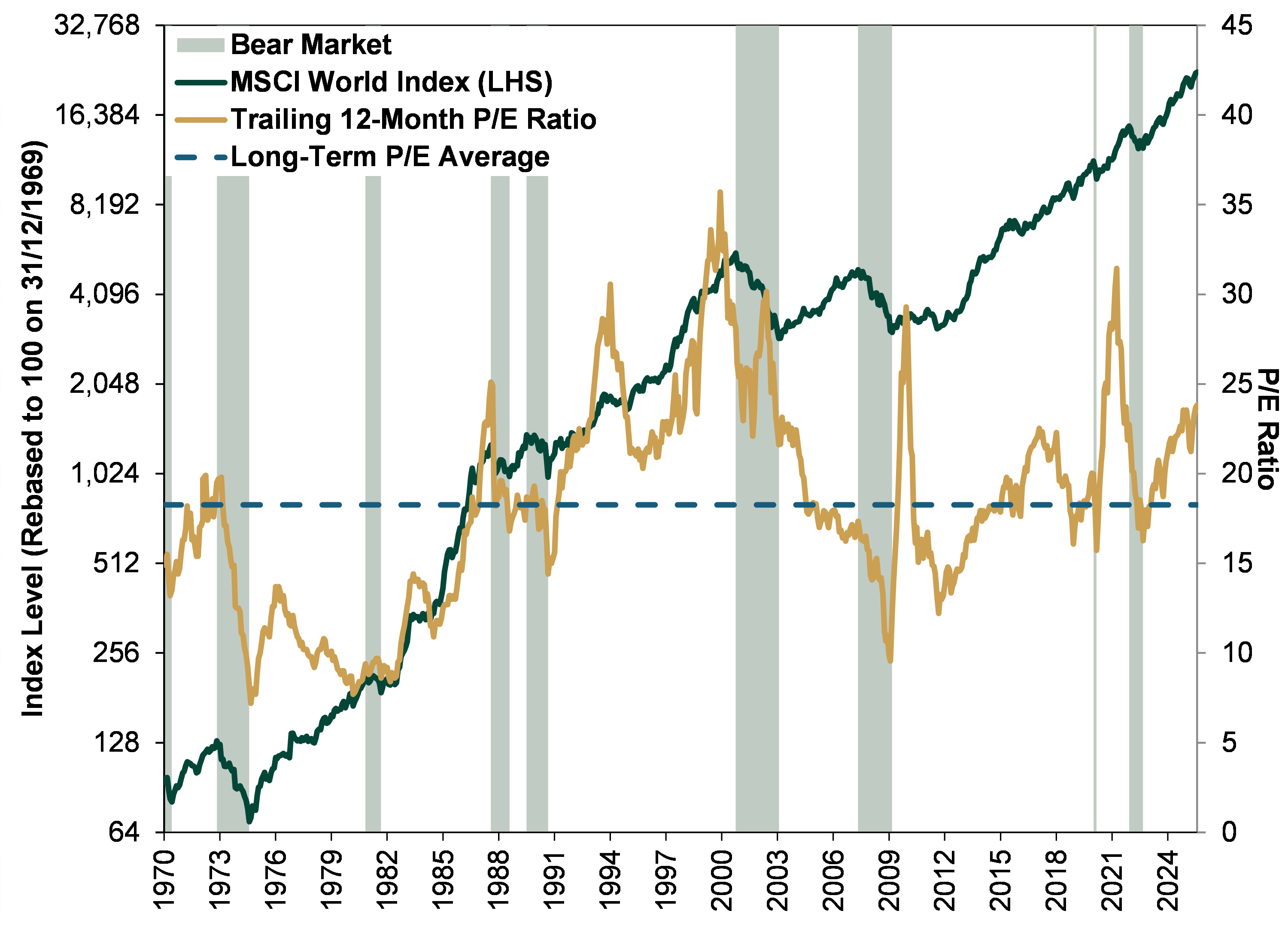

But is it true following such investment logic leads to better returns? When Fisher Investments Australia reviews the record, valuations don’t drive stocks—and adhering to an investment discipline based on them won’t work. On a first cut, Exhibit 1 shows stocks (green line) don’t have a clear-cut relationship with whether P/Es (yellow line) are below or above average (dashed blue line). There isn’t a reliable P/E threshold when bull or bear markets begin or end. In 1974, a bull market began at a P/E of 7. But then a bear market commenced in 1980 when its P/E was 9, not much higher, and ended the next year with P/Es little changed.

Exhibit 1: Stocks’ Valuation Doesn’t Determine Their Direction

Source: FactSet, as of 15/9/2025. MSCI World Index returns with net dividends and 12-month trailing P/E ratio, January 1970 – August 2025. Left-hand y-axis in base-2 logarithmic scale, which plots the same-sized percentage moves in equal increments graphically.

Or like we mentioned earlier, take the opposite extreme when P/Es rose above 30. The first time this occurred was 1994. Despite this P/E ratio’s unprecedented heights, it came in the middle of a long-running bull market. The second time: 1999, a great year for stocks before the early-2000s’ bear market commenced. The third time P/Es snuck above 30 was 2021—another nicely positive year for markets. Those getting cold feet then would have missed out. The lesson for investors: High P/E markets can always go higher and low ones lower. Valuations don’t tell you where stocks will go next, unlike the popular financial press Fisher Investments Australia reviews would have you believe.

Indeed, valuations can’t tell you stocks’ direction because they are backward looking and well-known. If investors follow stock valuations splashed on every financial website’s market data pages, whilst headlines blare any interesting statistic or trivia about them, then they probably hold little to no advantage. Any alleged market-moving insight is already priced in, as valuations are old news.

The late days of the 2007 – 2009 bear market are particularly instructive here, according to Fisher Investments Australia’s review of this period. Early in the downturn, P/Es slipped below average and even sub-15—decade-low levels. But that signal was based on past earnings, which markets already reflected. So when P/Es spiked as the recession destroyed earnings—hitting just below 30 in December 2009—that didn’t spook stocks. It was the beginning of a new bull market. Which raises another point: Both the P and the E in the metric can change and move. A high price relative to earnings may simply signal a company’s profit outlook is strong! That isn’t bearish.

Whilst Fisher Investments Australia’s review of stocks finds their assessment of future earnings is key (especially around 3 to 30 months ahead), what matters isn’t their absolute level or direction, but whether they miss or exceed prevailing views—what markets already priced. That is, stocks move mostly on surprise: the gap between reality and expectations. P/Es and similar metrics have nothing to say about future earnings’ surprise potential, which is why valuations aren’t predictive.

[i] Source: FactSet, as of 15/9/2025. MSCI World Index 12-month trailing P/E ratio, January 1970 – August 2025.

4 topics

Fisher Investments Australia® is a subsidiary of Fisher Investments—an adviser serving individuals and institutions globally. Fisher Investments Australia® is a trademark of Fisher Investments Australasia Pty Ltd, which provides services to...

Fisher Investments Australia® is a subsidiary of Fisher Investments—an adviser serving individuals and institutions globally. Fisher Investments Australia® is a trademark of Fisher Investments Australasia Pty Ltd, which provides services to...