Your brain vs your portfolio

Remember when Afterpay was everyone’s favourite stock? At $7 it was a bargain, at $40 it was a rocket ship, and by the time it hit $135 in 2021, it felt unstoppable. Then came the crash, and those who bought late were left nursing big losses.

Fast forward to 2025 and the ASX 200 is back in record-breaking territory, climbing from 8,201 in January to as high as 9,019 in August on the back of rate-cut optimism and strength in resources and tech.

On paper, things couldn’t look better. But scratch the surface and the same old story is unfolding.

Every bull run tempts investors into yesterday’s winners, only to leave them stranded when the music stops.

From lithium to BNPL, Australians have seen it before. The truth is, fundamentals don’t usually change overnight, our psychology does. And unless you can spot those biases in the moment, you risk turning a bull market into a personal bust.

Why behaviour matters as much as balance sheets

Behavioural finance has repeatedly shown that humans are hard-wired to make poor financial decisions under pressure. Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky’s work on prospect theory revealed how loss aversion (the tendency to fear losses more than we value equivalent gains), can shape every market decision.

Closer to home, the ASX is littered with examples.

In 2021, Pilbara Minerals (ASX: PLS) was trading at just $0.36. By late 2022, it had surged to $5.42, fuelled by surging lithium demand and a stampede of retail inflows. Yet by mid-2024, with spodumene prices collapsing from over US$7,000/t to US$1,000/t, the stock halved. Investors who chased performance were left holding the bag.

Similarly, Afterpay (ASX: APT) became the poster child of the BNPL boom. Its share price rocketed from $7.36 in 2018 to over $135 at its 2021 peak, before being swallowed by Block at a fraction of its former glory. Fundamentals didn’t suddenly evaporate; psychology flipped from euphoria to fear.

The biases behind performance chasing

Performance chasing doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It’s the by-product of several well-documented behavioural biases:

Recency bias and herd behaviour

Recency bias, also known as availability bias, is the tendency to overweight recent information or events without considering their true long-term probability. In markets, that means investors assume yesterday’s trend will continue tomorrow. A sharp rally convinces them that more gains are inevitable; a correction convinces them that further losses are around the corner.

This bias has real consequences. Inflows to “hot” ETFs and small-cap miners typically surge after those sectors have already run, not before. Morningstar’s 2024 data shows that the average Australian retail investor underperforms the very funds they invest in, because they enter after rallies and exit after drawdowns. Recency bias makes investors buy into bubbles and sell into bear markets, amplifying cycles rather than resisting them.

Loss Aversion

Loss aversion is the cognitive bias where the pain of a loss is felt more intensely than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. First formalised by Tversky and Kahneman in their Prospect Theory, it helps explain why investors often struggle to act rationally when markets turn against them.

In practice, this bias leads investors to cling to underperformers, unwilling to crystallise losses even when fundamentals deteriorate. A clear example was Fortescue Metals (ASX: FMG) investors anchoring on $25 highs in 2021 and refusing to sell, despite iron ore prices sliding sharply.

The emotional hurdle of “locking in” a loss outweighed the rational assessment of changing conditions.

Anchoring

Anchoring is the tendency to rely too heavily on a reference point, often a past price, when making decisions. Fixating on historical highs distorts rational analysis: a stock “returning to $50” can feel inevitable, even when earnings no longer justify it.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence bias occurs when investors overestimate their skill, knowledge, or control over outcomes. A string of good trades during the 2020–21 bull market convinced many retail punters they had an edge. In reality, the tide of liquidity lifted all boats—until it went out.

Confirmation bias

At the same time, major brokers like Goldman Sachs took a more cautious stance, warning that surging supply could push lithium prices lower in the medium term. In early 2023, for example, Goldman projected a global lithium supply surplus of 26% in 2024 and 57% in 2025, a view that contrasted sharply with the bullish sentiment dominating retail channels.

This divergence illustrates how confirmation bias can shape investor behaviour: upbeat narratives circulate and gain traction, while contrarian research—however well-founded—is often dismissed or overlooked.

The costs of emotional investing

These biases have a tangible cost. DALBAR’s 2023 Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior found that in 2022, the average U.S. equity fund investor lost –21.17%, compared with a –18.11% decline for the S&P 500. The culprit? Mistimed entries and exits, buying high and selling low, and excessive trading.

In Australia, SPIVA’s scorecards tell a similar story: in the five years to June 2024, more than 80% of actively managed equity funds underperformed the S&P/ASX 200. Yet flows continued into last year’s top-performing managers, perpetuating the cycle.

For individuals, the costs compound. Frequent trading raises transaction fees and tax liabilities, while the emotional toll of whipsaw markets often leads to worse decision-making under stress.

How to outsmart your own brain

Investors can’t rewire human psychology, but you can build systems that protect you from yourself:

1. Create checklists

Charlie Munger and other professionals swear by structured checklists. Ask: does this company have durable earnings growth? Is its balance sheet conservative? Does it have a sustainable competitive advantage?

2. Rebalance with rules

Set predetermined asset allocation bands and rebalance annually. This forces you to sell winners and top up laggards systematically, rather than emotionally.

3. Diversify themes & geography

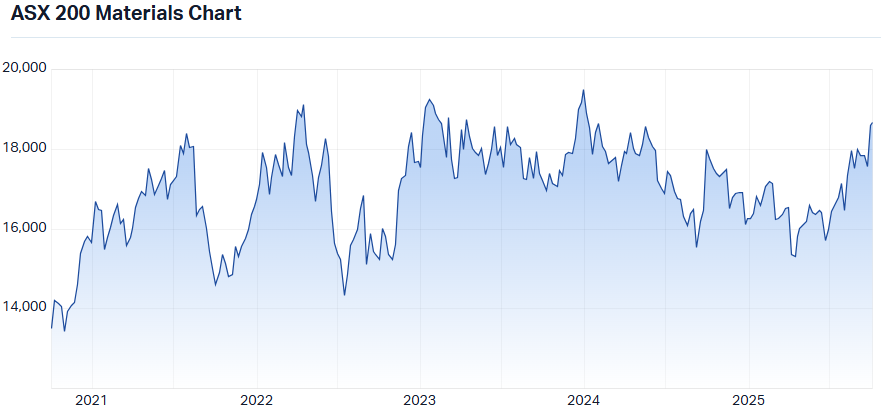

Thematic manias are seductive but dangerous. In 2023, Basic Materials surged while Health Care lagged; in 2024, the reverse occurred. Spreading capital across sectors and geographies reduces the risk of single-story portfolios blowing up.

4. Use dollar-cost averaging (DCA)

Regular contributions smooth volatility and reduce the temptation to time markets. While Vanguard’s research shows lump-sum investing often outperforms DCA over the long run, dollar-cost averaging can still protect investors from costly timing mistakes by enforcing discipline and reducing behavioural missteps.

5. Seek dissenting views

Make a habit of seeking out bearish research and asking: what would need to go wrong for this stock to underperform?

Nick Guidera of Eley Griffiths Group learned this lesson the hard way. Reflecting on a missed opportunity, “I let caution override conviction.” His takeaway was sharper still:

“Anchoring bias can disguise itself as insight.”

For investors, it’s a reminder that challenging consensus and testing your own assumptions is essential protection against narrative-driven mistakes.

Takeaways for Australian investors

For Australian investors, the lesson is simple: the best opportunities rarely lie in yesterday’s winners. They emerge when sentiment is darkest, when fear dominates headlines, and when biases push others to sell at any price.

Consider March 2020: as panic swept through markets, retail investors were rushing for the exits. Yet Paul Xiradis and his team at Ausbil saw opportunity, putting cash to work in quality names positioned for recovery.

As Xiradis later reflected, “Having a level head, learning from experience, doing the work, having a level of conviction to follow your instincts and also perceive value creates some fantastic opportunities.”

Similarly, Seneca’s Luke Laretive stresses avoiding the rush to thematic winners. In his playbook, he highlights opportunities in overlooked names, while trimming high-momentum stocks. His philosophy aligns with the idea that the best returns come not from chasing narratives, but from discerning value beside the crowd.

Outsmarting your own brain

Markets will always tempt investors to chase yesterday’s performance or hold onto hope for yesterday’s highs. But awareness is the first line of defence. By recognising biases: recency, loss aversion, overconfidence; and building disciplined systems, investors can avoid the behavioural traps that sabotage portfolios.

As the RBA’s rate-cutting cycle reshapes the ASX in 2025, the question for investors isn’t just what to buy, but how to think. Outsmart your own brain, and you’ll already be ahead of half the market.

Investor questions - let us know in the comments

- What are your biases and how do you manage them?

- What bias do you suffer from the most?

- What tips or practical steps do you take to help manage investment-related biases?

4 topics

3 stocks mentioned